Nationalism

advertisement

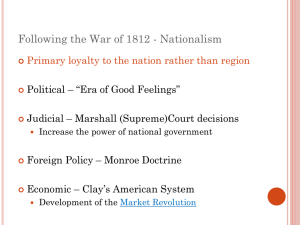

Nationalism Many scholars have struggled to define nationalism in a way that encompasses and makes sense of all the different situations in which it is employed. In general, it is an ideology in which the concept of the nation or nationality is the most important category by which humans define themselves. Nationalism necessarily categorizes people—one either is or is not a member of “my nation.” It thrives through the use of such elements as national folklore, symbols, heroes, sports, music, religion, and an idea that there is a national identity or character. Anthony D. Smith, a theorist of nationalism, has suggested that there are even criteria that must be in place for nationalism to exist. His list includes a physical homeland, either current or ancient, a high degree of autonomy among the citizens, hostile surroundings, memories of glory or defeat in battle, special customs, historical records, common languages and scripts, and what he calls sacred centers or places (17). This sort of nationalism is highly dependent upon the concept of the nationstate and probably represents the most common use of the term. This conception of nationalism has been used both to justify imperialism, to unite countries in times of war, and to describe the struggles for nationhood in colonized countries such as Ireland and India. However, nationalism has also been used to describe movements within sovereign nations, such as the Black Nationalist movement in the United States in the 1960s and 70s and Hindu nationalism currently seen in India. American Indian activists have also called for an American Indian nationalism, given especially that many of their tribes are sovereign nations themselves. One of the reasons nationalism is so difficult to define is that any discussion involving the subject necessarily spills over into cognate subjects such as race and racism, fascism, language development, international law, genocide, and immigration. Nationalism can also take many different forms. In other words, the central factor upon which the movement is based can be, for instance, religious, political, ethnic, or cultural. This further confuses the way the term is used and defined. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, for instance, the people of France had successfully united under such symbols as the tri-color flag, the sentimental power of the anthem “The Marseilles,” and the ideals of “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternity” (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity). This type of patriotism allowed the nation to feel as one in a way that had not been possible before the revolution. For the French, at least in overthrowing the monarchy, the loyalty inspired by nationalism helped to create a “free” society, the goal of the revolution. Throughout the nineteenth century, however, nationalism would be used to justify imperialism, jingoism, and xenophobia in countries such as Great Britain, the United States, Italy, and France itself. Some scholars also attribute the twentieth-century rise of fascism to nationalism taken to its extreme. In the late twentieth century the term came to be used most often to describe indigenous movements seeking autonomy, equality, and recognition. Most broadly, the term has been used to describe the way the people of a country define themselves. The idea that a "nation" is an entity, a known thing moving forward through time, is a relatively new one–having only been around since the eighteenth century or so. Although some historians believe that the "concept" of nationalism existed even in tribal communities and has likely been around since the beginning of humanity, modern theorists place its origins at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Before that period, they say, no one had more than local interests. Nationalism, for these theorists, was made possible by the industrial revolution, the widespread use of the printing press, and the rise of capitalism. All of these things relied on a large, literate, and culturally homogeneous population for their success. These contemporary theories, brought forth by people such as Benedict Anderson and Ernest Gellner, argue that nationalism is a “socially constructed” phenomenon. In other words, they believe that it is an artificial designation, imposed on the denizens of a country for social or political purposes. This belief does not reduce the power of the concept, but merely suggests that it is not a real, organic phenomenon arising from the true feelings and motives of the people of the country. As viable political entities, nations must concern themselves with defining what it means to be a nation. This is a challenge even for the most homogenous, linguistically and historical bound people, but it is a concern that is crucial to their existence. Literature, as a vehicle, helps to express nationalist ideas particularly well. If nations, or nationalist movements are indeed knowable entities moving forward in time, they need to speak, and literature gives them a voice to do just that. Post-revolutionary America, for instance, needed to come to terms with its independence, as well as to establish and put forward a national character. Washington Irving's THE SKETCHBOOK OF GEOFFREY CRAYON (1819) depicts characters struggling with these ideas. In one of Irving's most famous stories, "Rip Van Winkle," the main character goes to sleep for twenty years and wakes up in a world unfamiliar to him. What was once a pleasant, sleepy community now seems, to Rip, like a busy, contentious place, rife with disagreement. The American Revolution has taken place while he slept, but instead of focusing on political matters, Irving uses Rip to show the reader how daily life has changed in those lost years--daily life being more important than politics in the life of an ordinary man. This reading of American character helped early American take a step toward defining the national character of the fledgling country, and also helped readers understand the pain of independence from the mother country. Similarly, in William Butler YEATS's poetry, metaphors for national character and the struggle toward independence abound. In poems such as "The Stolen Child," "Chuchulain's Fight with the Sea," "Who Goes with Fergus?," and the long poem, "The Wanderings of Oisin," Yeats strives to invoke old Ireland, mystical and Celtic, in order that he might create for the modern country a pre-colonial image to which it might aspire. Ireland was the oldest of England's colonies, held for nearly 800 years, and an obstacle for Irish nationalists was finding a way to clearly distinguish what was Irish, from what was English. Yeats was such a nationalist poet, however, that he did not merely speak in metaphors. Much of his commentary on nationalism is not figurative at all, but is literally explored, in largely unambiguous language. In poems such as "Easter 1916," "To Ireland in the Coming Times," and "The Irish Airman Foresees his Death," Yeats is explicit, mourning the loss of lives in the struggle for independence and noting the toll years of oppression have taken on the Irish character. While both Irving and Yeats were working with countries struggling with defining their identities against the specter of English dominance, in 1897 Bram Stoker's novel DRACULA addresses the difficulty of nationalism and England itself. Count Dracula, whom Stoker portrays as everything that is foreign to England and the English characters, seeks to capture Mina, whose purity, intelligence, and kindness make her a perfect symbol of Victorian womanhood. In contrast, Dracula is mysterious, speaking in heavily accented English, living in a remote castle in Transylvania. He is Eastern as opposed to the very Western Mina, and worst of all, he is believed to be a vampire, the undead creature from Eastern European folklore. In his quest, Dracula purchases various pieces of real estate around London so that he may have resting places to protect him should he be caught outside as the sun rises. He has transported native soil from his homeland to deposit in these locations. This represents a kind of reverse colonialism, with the foreigner imposing himself upon England during the heyday of Victorian imperialism. The "good" character, that is the English, must unite to destroy the foreign menace and thus save the character of their nation. Other literary works, such as Salman Rushdie's MIDNIGHT'S CHILDREN (1983), are openly critical of nationalist movements, portraying them as dehumanizing movements that stress unity over humanity. In Midnight's Children, both the Indian nationalist movement and the Indo-Pakistani War (a nationalist driven war) come very close to destroying the future of India, all for the advancement of the idea of a strong, homogenous, modern nation. Just as nationalism itself is a term that is difficult to define, literary portrayals of nationalism take many different forms and approach the subject from many different angles. Minority groups, dominant religions and ethnicities, and political entities, both new and long-established may all embrace the ideology of nationalism. Literature, with its many layers of meaning, can express this ideology in the service of all these different groups. See Also: FAREWELL TO MANZANAR, A PASSAGE TO INDIA, KIM, THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, SURFACING For Further Reading: Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso (Revised Edition), 2006. Corse, Patricia. Nationalism and Literature: The Politics of Culture in Canada and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. Ignatieff, Michael. Blood and Belonging: Journeys Into the New Nationalism. London: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1995. Kohn, Hans and Craig Calhoun. Nationalism: A Study in Its Origins and Background. Edison, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2005. Smith, Anthony D. Nationalism: Theory, Ideology, History. London: Polity Press, 2001. Jennifer McClinton-Temple

![“The Progress of invention is really a threat [to monarchy]. Whenever](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005328855_1-dcf2226918c1b7efad661cb19485529d-300x300.png)