Discussion Questions for Spanish 201

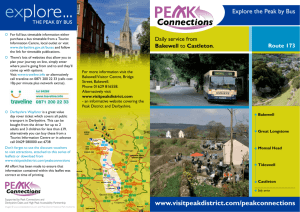

advertisement

Discussion questions to accompany Madre: Perilous Journeys with a Spanish Noun Spanish 201 1. Throughout the first half of the book Bakewell describes how she will never fit into Mexican society. She writes, “I stayed here for two years. I lived here. It became my home, although I never fully fit in.” (p. 13) Her blond hair and blue eyes, “New England, graduate-student look of high necklines and non-tailored, loose-fitting clothes” and her accent prohibit her from fully integrating. She thinks that if she buys “a pair of very high heels, stop wearing black, paint my fingernails (and, also, grow them), drop my neckline, and do something with my hair—other than tie it behind my head with the rubber band that held together yesterday’s newspaper” (p. 14) she just might begin to fit in a bit. Describe a time in your life when you felt like an outsider, no matter how hard you tried and fit in. If you are not a member of the dominant culture within a society, is it ever possible to fully integrate? Why or why not? If it is, how does one do it? Give examples of someone you know. 2. After describing an incident when a taxi driver asks if she has children, on pg. 18 Bakewell writes, “…Armando gave me a what-planet-are-you-from look…and continued to roll his eyes. As did all my friends here, when I played back the day’s events for them because to Armando and everyone else it was obvious. But to me, nothing ever is when it arrives in a foreign language, traveling over a foreign geography through foreign air and sunlight, bubbling up from foreign soil, where it had rested during a foreign night before.” (p. 18) Have you ever had a similar experience, either in the US or in another country? 3. Do you think Bakewell speaks in English or in Spanish with her Mexican friends and colleagues? 4. Pg. 27: In reference to Mexican painter, Magali Lara, Bakewell writes “Warm houses, kitchens, food, and savory smells came to her mind, when she thought of Mexican mothers.” What comes to your mind when you think of North American mothers, particularly your own mother, relatives or your friends’ mothers? 5. Pg. 31-32: “As it turned out,…” to end of paragraph. Excellent description of the subjunctive. Pg. 33: “This hopeful, optimistic, doubtful, ambiguous, ambivalent, uncertain, very real mode of discourse was convenient for Armando because it helped him sidestep touchy topics that concerned pinning things down to who, what when, where, and why.” What is your understanding of the subjunctive, i.e., when it is used or appropriate to use, and is there any aspect of the English language that allows speakers to communicate in the same way? 6. Neither Armando, Pablo nor the famous Mexican writer, Carlos Fuentes want to explicitly explain or translate any of the madre expressions to Bakewell. Do you think they would translate them if Bakewell were a man? 7. On pg. 83, Bakewell writes, “It’s not about mothers so much as it is about men and the disdain men have for their mothers…These mother insults are about power and control over women who exercise power and control over their children at home. The sons, especially, don’t like it.” A few pages later she writes, “The hijas (daughters) I’ve met down here don’t seem to have this knotted up relationship with their mothers.” Why do you think men do not like the “power and control” their mothers have over them but it does not seem to bother the women? 8. Pg. 93, when discussing piropos with a young college-aged woman, Odette, Bakewell writes, “Odette felt it was okay to have her body complimented by men on the street, but most compliments, she believed, were sexist.” How do you interpret Odette's belief/opinion? 9. Pg. 117 Bakewell writes, “Existential or practical, all six of us—Lilian, Beyti, Amparo, Juliana, Enrique, and I—not to mention others, over the past nine years, have talked about how women in the Spanishspeaking world go about their daily lives having to guess, ‘Are we part of the los or not?’ Do you agree with this statement or do you think most women do not question this aspect of the los?