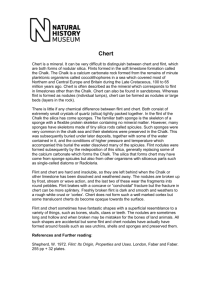

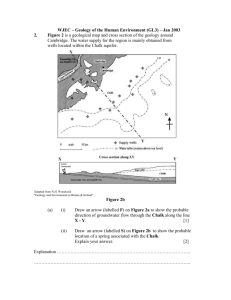

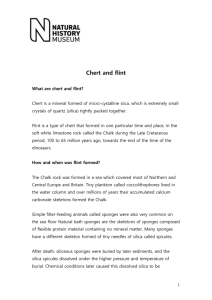

Banded flint

advertisement

Banded Flint Flints are the commonest hard stones in the south and east of England. They have all come out of the soft limestone formation called the Chalk, and are abundant as beach pebbles. They may also be found inland and a long way from their place of origin having been transported by people for industrial use, mainly in the making of pottery. Flint occurs in the Chalk in thin layers and in rows of scattered lumps (nodules). It consists of extremely small crystals of quartz (silica) tightly packed together. It is hard an insoluble, so that when the Chalk has been dissolved or washed away by weathering the flint remains behind; the nodules are broken up by frost, stream or wave action, and the last two of these wear the fragments into round pebbles. How did flint get in the chalk in the first place? The Chalk was formed in a sea which covered most of Northern and Central Europe and Britain during the Late Cretaceous, 100 to 65 million years ago. Chalk is mainly composed of the remains of minute planktonic organisms called coccolithophores. It also includes recognisable fossils formed from the shells and skeletons of larger sea creatures. Among these were the remains of simple animals called sponges, which lived on the sea bottom. The familiar bath sponge is the skeleton of a sponge, composed of flexible protein material containing no mineral matter, but some sponges have skeletons made of spicules, which are glass-like rods and bundles of rods made of opal (non-crystalline silica with water). Such sponges were very common in the chalk sea and their skeletons were preserved in the Chalk. This was subsequently buried under later deposits, together with some of the water contained in it, and the conditions of higher pressure and temperature which accompanied this burial the water dissolved many of the spicules. Flint nodules were formed subsequently by the redeposition of this silica, generally replacing some of the calcium carbonate which forms the Chalk. Flint nodules are, in fact, mineral growths. They sometimes have fantastic shapes with a superficial resemblance to a variety of things, such as a human foot, an animal’s head or a claw for example. The nodules are sometimes long and hollow and when broken may be mistaken for the bones of land animals. All such shapes are accidental, but some flints which have been formed around a fossil actually show its forms; common examples are the shells of sea-urchins and certain oyster-like shells. One common form of flint is a hollow nodule formed around the skeleton of a siliceous sponge. Some elongate and branching shapes are formed because the flint has replaced the burrows of invertebrate animals that are commonly present in the chalk. The broken surface of some flints known as ‘banded flints’ shows a pattern of parallel lines. These lines are generally thin and close together, but often broaden and become farther apart towards one end. They may be straight but are usually curved and may end abruptly. One theory for their formation is that in some flints the silica was originally deposited rhythmically in bands that differed in their original water content, which caused areas of the flint to weather differently to create this shape. Other theories relate to movement of water through flints after their original formation. The cause of these bands is still not known for certain. Further reading: Shepherd, W. 1972. Flint: Its Origin, Properties and Uses. London, Faber and Faber. 255 pp + 32 plates. Smith, A. B. and D. J. Batten (eds). 2002. Fossils of the Chalk. Palaeontological Association Field Guide to Fossils: Number 2. London, The Palaeontological Association. 374pp + 66 plates.