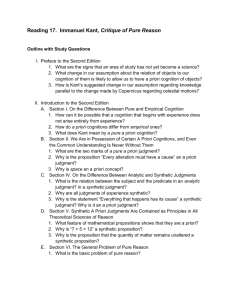

Kant Transcendental Logic

advertisement

Title of Work: Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, Transcendental Logic: Introduction, Analytic of Concepts Chapter 1 Date of Meeting: 4/2/09 Preparer of Notes: Paulinator Summary of Transcendental Logic Introduction: Summary of Analytic of Concepts, Chapter 1: Detailed Notes: Transcendental Logic Introduction: Idea of a Transcendental Logic I. Logic in General a. Knowledge springs from two sources of the mind: i. Intuition: capacity of receiving representations – object is given ii. Understanding: power of knowing an object through the representations – the object is thought, concepts are produced b. Both may be either pure or empirical i. Pure: no mingling of sensation with the representation, and thus contain only the form under which something is intuited or thought ii. Empirical: sensation is the material of sensible knowledge c. Only pure intuitions or pure sensations are possible a priori. d. Only through the union of understanding and sensation can knowledge arise; nonetheless, we should distinguish carefully between the two: i. “Without sensibility no object would be given to us, without understanding no object would be thought. Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind” (B75). ii. Distinguish between the elements of knowledge: 1. Aesthetic: the science of the rules of sensibility in general 2. Logic: the science of the rules of the understanding in general e. Logic can again be treated under a twofold division: i. Logic of the special employment of the understanding: an organon for this or that particular science ii. General logic: treats of understanding without regard to the difference in the objects to which the understanding may be directed f. General logic further divided into pure or applied i. Pure general logic: abstracts from empirical conditions. Deals only with principles a priori, is a canon of understanding for the formal employment of reason ii. Applied general logic: because it concerns the application of the understanding to particular instances, it has empirical principles 1 g. Two notes on pure general logic: i. It deals with nothing but the mere form of thought, abstracting from all content of understanding, difference in objects, etc. ii. It has nothing to do with empirical principles; everything in it must be entirely certain a priori h. Pure general logic : applied general logic :: pure ethics : doctrine of virtues II. Transcendental Logic a. Transcendental logic differs from pure general logic i. Firstly, although pure general logic abstracts fully from the content of the understanding, to deal only with the forms, still its content can be either empirical or transcendental (A53). ii. Transcendental logic, on the other hand, is a pure logic which contains solely the rules of the pure thought of an object, excluding any mode of knowledge with empirical content. iii. Also, transcendental logic is concerned with treating the origin of the modes in which we know the objects b. Remember that ‘transcendental’ signifies such knowledge as concerns the a priori possibility of knowledge (not merely any a priori knowledge whatsoever) c. Definition of transcendental logic: science of the laws of understanding and of reason insofar as they relate a priori to objects (B82). III. The Division of General Logic into Analytic and Dialectic a. The paradox of truth: i. Truth consists in the agreement of knowledge with its object ii. Thus the object must be distinguished from other objects iii. A general criterion of truth is that it is valid in each and every instance of knowledge, however the object might change iv. Such a criterion, however, cannot take account of the varying content of knowledge v. “A sufficient and at the same time general criterion of truth cannot possibly be given … so far as its matter is concerned, no general criterion can be demanded” (A59) b. If we regard merely the form of knowledge, then logic can provided universal and necessary rules of the understanding which furnish the criteria of truth c. Still, this is not sufficient alone, because knowledge, even if it does not contradict itself, still might be in contradiction with its object d. We may now divide general logic into analytic and dialectic: i. The analytic resolves the formal procedure of the understanding, exhibiting the a priori elements of all logical criticism of our knowledge ii. The dialectic makes the mistake of treating logic, which is merely a canon of judgment, as an organon for the production of assertions 1. Dialectic is thus a logic of illusion: “logic teaches us nothing whatsoever regarding the content of knowledge, but lays down only the formal conditions of agreement with the understanding” (B86) 2. In the work, ‘dialectic’ = critique of dialectical illusion 2 IV. The Division of Transcendental Logic into Transcendental Analytic and Dialectic a. Transcendental Analytic: deals with the elements of the pure knowledge yielded by understanding, and the principles without which no object can be thought. i. The logic of truth ii. Merely a canon for passing judgment upon the empirical employment of the understanding b. Transcendental Dialectic: a critique of the dialectical illusion of treating the logic as an organon which can by itself judge synthetically Transcendental Analytic I. The four chief concerns of the transcendental dissection of a priori knowledge into the elements yielded by the pure understanding alone: a. The concepts must be pure and not empirical b. The concepts belong to thought and understanding (not sensibility and intuition) c. The concepts are fundamental (i.e., not derivative or composite) d. The concepts must be arranged into a complete table which covers the whole field of the pure understanding II. Analytic of concepts: “dissection of the faculty of understanding itself, in order to investigate the possibility of concepts a priori by looking for them in the understanding alone, as their birthplace, and by analyzing the pure use of this faculty” (A66). Analytic of Concepts I. The clue to the discovery of all pure concepts of the understanding a. What we want is to determine the various concepts that make a faculty known b. However, we need to be assured of the completeness and unity of these concepts, which is a difficult thing to do methodically c. But transcendental philosophy has an advantage: it proceeds according to a single principle, since the understanding is an absolute unity d. Therefore the unity of the understanding is the clue to the discovery of all the pure concepts of the understanding II. The transcendental clue to the discovery of all pure concepts of the understanding: The logical employment of the understanding in general a. So far we have explained understanding merely negatively, as non-sensible b. But now we can explain understanding as yielding concepts, and thus as discursive rather than intuitive i. All intuitions rest on affections (being affected) ii. All concepts rest on functions (fungor = ‘to do something’) c. Concepts are based on spontaneity of thought; sensible intuitions on the receptivity of impressions d. Only intuitions are in immediate relation to objects i. Concepts, on the other hand, are not related to an object immediately, but rather to some other representation of it (whether that representation is a sensible intuition, or even another concept of the object) ii. Note that both intuitions and concepts are representations for Kant, differing in the production and in the relation to the object 3 e. Judgment: the mediate knowledge of an object, i.e., the representation of a representation of an object i. A judgment applies one concept to another concept, or to a sensible intuition (e.g. ‘all bodies are divisible’) ii. Thus judgments are functions of unity among our representations III. The plan for the analytic of concepts: a. Reduce all aspects of the understanding to judgments b. Represent the understanding as a faculty of judgment c. Give an exhaustive statement of the functions of unity in judgment d. This will allow us to discover the functions of the understanding The Logical Function of the Understanding in Judgments I. The logical function of the understanding in judgments a. Abstracting from all content of judgment and considering only the form of the judgments allow us to form the table of judgments (at B95) b. Note that the table has four heads, each of which has three moments II. Kant is concerned to address possible misunderstandings which might arise from a confusion of his table of judgment with the technical distinctions made by logicians: a. Under the Quantity of Judgments confusion might arise concerning his addition of ‘singular’ to ‘universal’ and ‘particular’ i. For logical employment, there is no difference between singular and universal judgments ii. However, when considering knowledge in general, a singular judgment stands to the universal as unity to infinity, and so is really distinct iii. N.B. This is the form of Kant’s refutation of mere logicism… b. Under the Quantity of Judgments, we should distinguish infinite and affirmative judgments, since transcendental logic considers the worth or content of a logical affirmation – “the soul is non-mortal” is a real affirmation c. The Relation of Judgments i. Categorical: relation of predicate to the subject; two concepts ii. Hypothetical: relation of ground to consequent; two judgments iii. Disjunctive: relation of the divided knowledge and of the members of the division, taken together, to each other; several judgments in their relation to one another 1. The disjunctive judgment is a community of judgments, even though the sphere of one excludes the other 2. Thus the totality of the disjunctive judgments determines, in the totality itself, the true knowledge d. The Modality of Judgments contributes nothing to the content of the judgments (as did the other functions of judgment), but rather “concerns the value of the copula in relation to thought in general” (B100) i. The problematic expresses only logical (not objective) possibility ii. The assertoric deals with logical reality or truth 4 iii. The apodeictic thinks the assertoric as determined by the laws of the understanding, and there as affirming a priori; thus it expresses logical necessity (A76). The Pure Concepts of the Understanding, or Categories I. Section 10 a. Transcendental logic has the manifold of a priori sensibility as material for the concepts of pure understanding (whereas general logic had to abstract from all content of knowledge) b. Space and time contain a manifold of pure a priori intuition which are the conditions of the receptivity of our minds i. But how is this manifold to be known? ii. Only by the spontaneity of our thought going through and taking up, connecting this manifold in a unifying concept. c. This process is synthesis: “the act of putting different representations together, and of grasping what is manifold in them in one act of knowledge” (B103) i. Such a synthesis is pure if the manifold is space and time, i.e. not empirical, but rather given a priori ii. The knowledge which results from synthesis may be crude, confused, and in need of analysis, but still it is absolutely essential for knowledge d. “Synthesis in general … is the mere result of the power of imagination, the blind but indispensable function of the soul, without which we should have no knowledge whatsoever, but of which we are scarcely ever conscious” (B104) e. Pure synthesis, represented in its most general aspect, gives us the pure concepts of the understanding i. Transcendental logic is concerned with bringing to concepts the pure synthesis of representations ii. The work of the concepts is to give unity to the pure synthesis of the manifold of pure intuition by the imagination. Thus the concepts furnish the third requisite for the knowledge of an object II. The Table of Categories a. The same function which unifies various representations in a judgment also gives unity to the mere synthesis of various representations in an intuition. b. This latter unity is precisely the pure concept of the understanding i. The understanding produced the logical form of the judgment ii. Now the same understanding introduces transcendental content into its representations through the same operations, by means of a synthetic unity of the manifold in intuition in general iii. Thus the pure concepts of the understanding correspond to the functions or judgments of the understanding c. Only through the concepts can the pure understanding understand anything in the manifold of intuition, can it think an object of intuition d. The division of concepts is developed systematically from a common principle, namely the faculty of judgment, and thus is exhaustive e. The predicables are the derivative concepts which result from the pure concepts 5 III. Section 11 (Some notes on the categories) a. The table of categories may be divided into two groups: i. Mathematical: the concepts concerned with objects of intuition ii. Dynamical: the concepts concerned with the existence of these objects, in their relation either to each other or to the understanding b. The third category in each class always arises from the combination of the second category with the first i. However the third category is not derivative; it is still primary ii. The combination of the first and second categories requires a special act of the understanding which is not identical with what is exercised in the first and second concepts c. Community is in accordance with the form of disjunctive judgment based upon his early work to show the unifying work of disjunction to display the whole IV. Section 12 (A consideration of the ancient notion of the transcendentals) a. The ancient transcendentals (unum, verum, bonum) were thought to be predicates of things i. In actuality they are the logical requirements and criteria of all knowledge of things in general ii. They are the categories of quantity, i.e. unity, plurality, and totality 1. Unum = unity of concept 2. Verum = plurality, insofar as the greater the number of true consequences that follow from a given concept, the more crieteria there are of its objective reality 3. Bonum (perfection) = plurality together leads back to the unity of the concept, which is totality b. Thus the transcendentals, if taken to be properties of the things themselves rather than the a priori concepts of the understading, result from dialectic. c. The concepts of unity, truth, and perfection do not make any addition to the table of categories Questions, Notes: 6