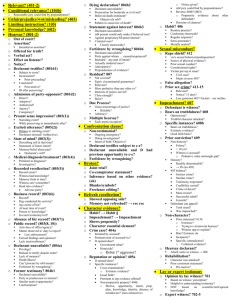

EVIDENCE (LAW 543) - University of Hawaii

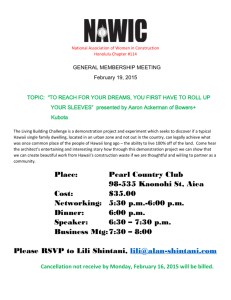

advertisement