Liverpool as a diasporic city

advertisement

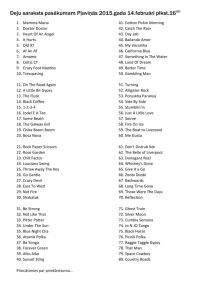

Liverpool as a Diasporic City John Herson Liverpool John Moores University ‘The streets of Liverpool during the emigrant season present stirring spectacles of cosmopolitan animation, and the city itself is the temporary resting place of visitors from all parts of the hemisphere. Russians, suspicious and sullen, … Finns and Poles, men of fierce and haughty natures, … Germans, quiet and inoffensive, brave and determined … the flaxen-haired Scandinavians, paragon of nature’s handiwork, erect and stately.’1 With these poetic, if crude, stereotypes the Liverpool Mercury sought to encapsulate Liverpool’s emigrant trade in 1887. The paper’s correspondent described with pride the city’s role ‘as the European centre of emigration’, and Liverpool’s importance in the worldwide scattering of European peoples has been an element in its heritage ever since. It is mainly in this sense that Liverpool is perceived as a diasporic city, but the term diaspora must also include the city as the residence of diasporic settlers and sojourners. This paper seeks to outline the scale and character of emigration through Liverpool and its significance for the city. It also examines the impact of nineteenthcentury in-migration and questions whether it is useful to view Liverpool as a diasporic city. It suggests that Liverpool’s ambiguous nineteenth-century identity reflected the tensions of its complex migrant connections. Emigrants through Liverpool, 1825-1913 It is easy to assume that the emigrant trade was important for Liverpool’s economic and social development, but there has been little attempt to examine this proposition in any depth. Furthermore, despite frequent references to the scale of emigration through Liverpool in the nineteenth century, nobody seems to have produced time series data on the actual numbers of emigrants passing through from the 1820s to the Great War. Neither Liverpool’s changing position relative to other UK ports, nor the significance of various emigrant destinations for Liverpool has been documented. This section of the essay is based on data that remedies these deficiencies. Table 1 Extra-European passengers from British and Irish ports, 1825-1913 Port Number Liverpool 12,287,185 London 2,248,625 Plymouth 490,588 Southampton 1,812,414 Other English ports 295,644 Scottish ports 1,739,374 Irish ports 3,105,346 Total 21,979,175 Sources: see note 2. 1 % 55.90 10.23 2.23 8.25 1.35 7.91 14.13 100.00 Liverpool was the most important emigrant port in the British Isles and table 1 shows the extent of its dominance. Over twelve million passengers passed through the city between 1825 and 1913, nearly 56 per cent of all those leaving UK ports.2 London, the next biggest, took less than a fifth of Liverpool’s total, and those emigrating directly from Ireland were only a quarter of Liverpool’s number. Liverpool’s top position amongst British ports was never challenged before 1914, but there were some changes in the general picture. The port only achieved overall domination – more than half the outward passengers – in 1843. Its heyday, when it had more than 60 per cent of the traffic, lasted from 1850 to 1874. In the depressed years of the late-1890s Liverpool’s proportion dropped below half, but it enjoyed one last emigrant bonanza in the years before the Great War (figure 1). This again pushed its proportion of passenger traffic over 50 per cent - and indeed beyond 60 per cent until 1912. Table 2 Destinations of extra-European passengers from Liverpool, 1825-1913 Area Total % United States 9,097,474 74.04 British North America 2,393,420 19.48 Australia/New Zealand 452,711 3.68 ‘East Indies’ 80,018 0.65 West Indies 9,521 0.08 South Africa 20,138 0.16 Central/South America 71,836 0.59 Unspecified destinations 162,067 1.32 Total 12,287,185 100.00 Sources: see note 2 Liverpool’s role in the emigrant trade was multi-facetted. Although dubbed the ‘second city of empire’, Liverpool’s main emigrant traffic was to the United States. Over nine million people left Liverpool for the US, almost three-quarters of the total passengers going to extra-European destinations (table 2 and figure 1). Two features stand out in relation to the American traffic – its sheer size and its volatility. In all but three years (1825 and 1911-12) more went to the US than to all the other destinations combined. Even so, the demand for passages was so volatile that in peak periods it was over four times as great as in the troughs. The port nevertheless played a significant role in transporting people to the British empire and Liverpool’s secondranked emigrant traffic was generally that to British North America. Although this was to British dominions, for most of the period the traffic was an adjunct to the dominant US route and many of the migrants sooner or later crossed into the US. This was particularly the case with the Irish famine emigrants around 1847.3 Canadian traffic did not become significant on its own account until after Confederation in 1867. The numbers going to Canada never exceeded those going to the US, but they came close in the four years before the Great War. The only other large numbers of emigrants through Liverpool in the nineteenth century were to Australia. Liverpool’s entry into the Australian market really came with the gold rush of the 1850s, but the end of easy gold finds diminished numbers after 1858 and Liverpool shipping lines left the trade between 1857 and 1866.4 The traffic was effectively dead by 1873 and only revived to a very modest degree in the 1900s. London became the predominant port of embarkation for Australia. The 2 number of passengers travelling to destinations elsewhere was small in relation to the big flows to North America and Australia. Even so, their political and economic importance may have been greater than the numbers might suggest. From 1825 to 1913 nearly 344,000 passengers went to Central and South America, the East Indies, West Indies, Africa and other unspecified destinations. Some would have been permanent emigrants, but most were colonial administrators, troops, traders and business representatives. The port was a significant conduit for these people, although London and later Southampton were more important ports for imperial functionaries. These traffics and the major emigrant flows to Canada and Australasia nevertheless indicate Liverpool’s role in peopling the British empire. Between 1825 and 1910 just over 60 per cent of passengers to British North America passed through Liverpool, and the proportion was over 80 per cent from the 1880s to the mid-1900s. Over 40 per cent of those going to Australia from the mid-1830s to the early-1860s left from Liverpool. Many emigrants were Irish and most went to the westward-colonising United States. For those going to the British empire the journey was inherently more ambiguous. As Alvin Jackson has argued, for the Irish ‘the empire was both an agent of liberation and of oppression; it provided both the path to social advancement and the shackles of incarceration.’5 Ironically, the Irish emigrants could be seen as colonised and exiled people who became, in turn, colonisers, exploiters and enforcers of British imperialism. Many, particularly those going to Canada, came from Protestant loyalist backgrounds, but the Celtic-Catholic Irish also played a major role in settling, administering and policing the self-governing dominions.6 Liverpool’s Irish connection has tended to obscure the port’s importance for emigrants from Britain, particularly England and Wales, as well as from the continent of Europe, and an estimate of the ethnic breakdown of Liverpool’s emigrants from 1853 to 1912 is shown in table 3.7 About 4.4 million continental transmigrants passed through Liverpool. They formed under 10 per cent of passengers from 1853 to 1862, between 20 and 50 per cent from 1863 to 1892 and over half from 1893 to 1912. The transmigrants came from many parts of continental Europe, but the main flows were from Scandinavia, Germany, Russia and Poland. Liverpool played a particularly important role in the exodus of Jews from the Russian territories following the pogroms of 1881-82.8 Table 3 Estimated origins of passengers through Liverpool, 1853-1912 Years Irish % Irish Continental % British Transmigrant Transmigrant 1853-62 606,292 50.38 110,055 9.15 487,005 1863-72 421,285 29.04 368,686 25.42 660,635 1873-82 215,255 15.46 580,355 41.68 596,907 1883-92 152,460 7.76 808,700 41.18 1,002,856 1893-1902 66,945 5.05 862,072 65.04 396,358 1903-12 63,692 2.13 1,710,364 57.14 1,219,456 Total 1,525,929 14.77 4,440,231 42.99 4,363,216 Source: see note 7 The Famine emigration dominates perceptions of Liverpool’s importance for Irish overseas emigration. Over a million Irish passed through in the Famine decade (1845-54) and in the 1850s more than three-quarters of the emigrant Irish made the passage to Liverpool to pick up ships going overseas. This changed after 1859 when 3 % British 40.47 45.54 42.86 51.06 29.91 40.73 42.24 the Cunard and Inman lines began to call at Queenstown (Cobh). Most other lines later stopped there or at Moville (Derry) for Irish passengers, and Liverpool’s hold on the Irish trade was diminished. By the 1870s and 1880s only around 20,000 Irish emigrants were passing through Liverpool each year, and the numbers dropped below 10,000 thereafter. The port’s role in the trauma of Famine emigration was a relatively short phase that has distracted attention from the bigger picture. The British, and particularly the English and Welsh, rivalled the transmigrants as the bread and butter of Liverpool’s emigrant trade after the Famine crisis (table 3). About 4.4 million British emigrants passed through between 1853 and 1912, nearly three times the number of Irish. The emigration of British people was notably volatile, with particularly steep declines in the mid-1870s and again in the second half of the 1890s. Liverpool disproportionately lost out in the late-1890s because of depression in America and the relative growth of empire emigration to Australasia and South Africa through Southampton and London. An increasing proportion of British passengers, particularly to North America, were also transient workers seeking short-term jobs overseas.9 They passed through Liverpool continuously as a generally invisible stream. The impact of the emigrant trade Liverpool’s importance for emigrants was one element in its complex and dynamic nineteenth-century identity. The city’s shippers sought passengers from Britain, Ireland and all the countries of continental Europe and transported them to both imperial and foreign destinations. The balance of passengers’ origins and destinations was never stable, however, and the trade often shifted in orientation in response to changes in its world market. Although the statistics amply demonstrate Liverpool’s dominant role in the emigrant trade, assessing its impact on the city is more difficult. The first issue to be considered is the handling of emigrants as they passed through the city. Liverpool’s notorious treatment of emigrants, especially the Irish, in the mid-nineteenth century has received much attention. People arriving in Liverpool had to find accommodation, book an onward passage and provision themselves for the voyage. Passages were sold by emigrant brokers who charged a commission of 10 to 15 per cent, and the brokers spawned a network of ‘runners’ who competed to channel emigrants to them.10 Often the runners and their associates were lodging house keepers and they commonly ran stores selling shoddy and over-priced provisions to travellers. The whole system battened on the ignorance and vulnerability of travellers, particularly the Irish. Many were captured by such people, imprisoned in squalid lodgings, relieved of their money and sold passages that might be fraudulent or subject to interminable delays. Terry Coleman and others have documented the scandal of the Liverpool system.11 The aim here is to arrive at some estimate of its size. In 1851 Sir George Stern, ‘resident at Liverpool’, estimated there were 673 registered lodging houses in Liverpool, of which he thought 286 were occupied by emigrants.12 The Irish were dominant in the trade, as they were amongst the runners, and emigrant lodgings were particularly concentrated in the slums behind Clarence Dock and near Princes Dock.13 It is difficult to say how many runners there were, but in 1851 William Tapscott, a passage broker with a dubious reputation, hazarded that ‘there are thousands of such persons.’14 Then there were the so-called dealers who specialised in exploiting emigrants. John Bramley Moore, a magistrate, gave evidence that of 900 he had convicted for short weights and cheating, between 500 and 600 4 were provision dealers and grocers guilty of ‘impositions on emigrants. They are a class quite apart from the respectable tradesmen of the town’.15 All these frauds brought significant funds into the Liverpool economy and particularly to parts of its Irish population. In 1851 there were 206,015 recorded emigrants, most of them Irish. On average the runners received 7½ per cent of each six pound fare totalling £92,707 15s 0d. Each emigrant might be divested of around ten shillings for accommodation and provisions by Irish compatriots, which meant another £103,007 10s entered the economy. The total of £195,715 5s amounts to about £2 6s per Irish-born resident of Liverpool at that time. Thousands of people in mid-century Liverpool could therefore make money from the informal economy of the emigrant trade, though the profits were unevenly spread. Steamships took over most of the North Atlantic routes in the 1860s and the shipping lines took bookings directly through agents in the exporting regions. This reduced opportunities for fraud in Liverpool. Transmigrants from Europe, as well as emigrants from Britain and Ireland, increasingly had an integrated passage from their home area to Liverpool and thence overseas. Lodgings were arranged in the city and the spectre of runners suborning frightened, gullible, travellers faded away. Ship departures became more reliable and the time that had to be spent in Liverpool was reduced. Accommodation was in commercial hotels and hostels rather than the squalid lodgings of the 1850s. On census night in 1881, for example, eight premises were clearly accommodating European transmigrants and they housed a total of 402 people from the countries shown in table 4. Lodgings became larger and more organised and they provided an entrepreneurial niche for foreigners. Gore’s Directory listed fifty two commercial boarding houses in Liverpool in 1881 of which sixteen had proprietors with continental European names. They were probably engaged in the emigrant trade, though some also catered for foreign seamen. By 1910 there were ninety two such establishments, a growth that reflected the boom in transmigrant traffic in the 1900s. Most emigrants now passed rapidly through Liverpool but some were forced into the Poor Law system. Between 1881 and 1888 812 emigrants, mostly sick, were admitted to Liverpool Workhouse. Shipping companies paid for their relief. Table 4 European transmigrants in Liverpool, 3 April 1881 Country of birth No. Sweden 158 Norway 34 Germany/Prussia 56 Denmark 13 Poland 93 Switzerland 34 Italy 11 France 3 Total 402 Source: Census enumeration returns, 1881, Liverpool Others posed more of a problem. Sometime in the 1880s, a group of ‘Syrian Arabs’ ended up in Liverpool. They had paid in Marseilles for a passage to New York via Le Havre and Liverpool, but had been refused permission to land in the US. They were sent back to Le Havre and the authorities there ‘coaxed some captain of a British vessel to bring them back to Liverpool.’ They were sent to the Workhouse and spent 5 five months there - ‘we had the greatest possible difficulty getting rid of them’ according to the Liverpool Vestry clerk.16 Neither the steamship lines nor the Board of Guardians willingly took responsibility for emigrants in distress, an example being Cunard’s treatment in 1892 of 140 Jews stranded in Liverpool by an outbreak of cholera. After four weeks the company turned them out of their lodgings and disclaimed any further responsibility for their maintenance. The Board of Guardians refused to take them into the Workhouse and the Liverpool Jewish Board of Guardians ended up supporting them over the winter.17 Jobs and entrepreneurial opportunities were created in Liverpool to cater for the emigrants, but their number relative to the size of the city was not great. Liverpool was analogous to a great railway station. Thousands passed through but relatively small numbers were needed to process them. Unlike cargoes, the migrants could transport themselves and many of their belongings. Porters and carriers were casually employed moving people and luggage from the stations and lodgings to the landing stages, but it is difficult to say how many depended on the emigrant trade. Some extra railwaymen dealt with transmigrants on trains from Hull, Grimsby and London. The North Eastern Railway transported at least 636,000 emigrants from Hull to Liverpool between 1890 and 1910 and in 1895 the London & North Western Railway opened Riverside Station for boat trains.18 The emigrant traffic was an element in the endemic controversy over Liverpool’s dock facilities that reflected ambiguity in the role of the port. Competition between the passenger lines resulted in bigger ships, and there were conflicting pressures from passenger lines wanting bigger facilities and cargo lines resisting them as unnecessary and expensive.19 As a result, the facilities were perennially inadequate for the passenger liners, though enough was invested to more or less keep up with basic needs.20 This created transient construction work and more permanent jobs on the waterfront. Conversely, the move of the White Star liners to Southampton in 1907 was an economic loss to the port and the city. Much of the early traffic in sailing ships to North America had been in the hands of US companies, though firms based mainly in Liverpool ran the Australian trade of the 1850s and 1860s. The rise of the steamship lines brought a good deal of nominal control back to Britain, and the key players of the 1870s and 1880s – Inman, Cunard, White Star, National and Guion – were mostly based in Liverpool.21 In that sense, the profit they made from the passenger trade flowed through Liverpool, but as public limited companies most of the dividends went to shareholders scattered throughout the country, the empire and elsewhere. The volatility of the emigrant trade meant that profits were by no means guaranteed.22 Some indication of the fare income from emigrants is shown in table 5.23 It suggests the North American emigrant trade from Liverpool earned fares of over £56 million in the whole period, well over Table 5 Estimated fare revenue from North American emigrants, 1825-1913 Years Revenue Avg. per Year 1825-44 £1,576,997 £78,850 1845-64 £12,794,299 £639,715 1865-84 £15,575,334 £778,767 1885-1904 £13,901,922 £695,097 1905-13 £12,412,890 £1,379,210 Total £56,261,442 £632,151 Source: see note 23 6 £600,000 per year. The years from 1905 to 1913 stand out as Liverpool shipping’s final emigrant bonanza. A lot of this money entered the Liverpool economy in terms of seamen’s wages, port charges, insurance premiums, office expenses, purchase of ships’ provisions, laundries and so on. The money spent willingly or otherwise in Liverpool by emigrants themselves must be added to this figure. Nevertheless, the overall impression is that the economic impact of the emigrant trade on Liverpool was less than might be imagined. Liverpool was the focus of a world-wide emigrant complex, but for most of the city’s inhabitants the passenger liners at the landing stage were a showy presence of little relevance to their daily lives. Liverpool’s immigrants What of the city as the recipient of immigrants? They did have a substantial impact on Liverpool’s social character throughout the nineteenth century. It is important to remember that in-migrants from other parts of Britain were the biggest group of outsiders - in 1851 nearly 47 per cent of Liverpool’s adult population had been born in Britain but outside Liverpool. Historians have neglected the experience and identity of these people, particularly those from other parts of England. The Irish have attracted more attention. The Famine increased Liverpool’s Irish-born population to 83,813 in 1851 (22.3 per cent of the total) and Irish people continued to settle for the rest of the period, although their numbers dropped. By 1911 the Irishborn were down to 34,632 (4.6 per cent), but they still outnumbered Liverpool’s other overseas immigrants by more than eight to one and there were, in addition, tens of thousands with Irish or part-Irish descent. It might be assumed that the Irish who settled in Liverpool were those too destitute, ill or unskilled to go any further – a sort of flotsam left from the two million or so who passed through on the way to other places. At the time of the Famine there was doubtless some truth in this, but Liverpool had major advantages as a destination for the Irish. It was close to home and contacts could be maintained easily. The city’s trade provided many opportunities for Irish entrepreneurs in both the informal economy and in more ‘respectable’ occupations, a class deserving of further study.24 The docks, construction, domestic service and transport offered thousands of jobs for the unskilled, though with poor conditions, low pay and little security. The identity of the Irish was ambiguous. They originated in that part of the United Kingdom whose status was part colonial and part metropolitan.25 Many if not most of the Catholic Irish had a conditional or even hostile relationship with the British population. Nevertheless, for good or ill they generally spoke the common language and shared major elements of the same cultural tradition.26 This differentiated them from most of the other immigrants who came to Liverpool. Table 6 Foreign and empire-born, Liverpool, Manchester and London, 1901 Liverpool Manchester London Origin No. % No. % No. % Russia/Poland 3,894 33.5 7,138 53.4 53,537 31.8 Other Europe 4,054 34.8 4,137 31.0 74,758 44.4 Overseas Foreign 940 8.1 446 3.3 6,773 4.0 British empire 2,740 23.6 1,636 12.3 33,350 19.8 Total 11,628 13,357 168,418 Source: 1901 Census County Tables, Lancashire & London, Tables 36-7 7 It is easy to form the impression that Liverpool had an exceptionally large cosmopolitan element in its population in the nineteenth century, and that this distinguished it from other British cities. In 1907 Ramsey Muir observed that ‘those who inhabit this vast congeries of streets are of an extraordinary diversity of races – few towns in the world are more cosmopolitan,’ and the theme of cosmopolitanism, albeit critically assessed, runs through the latest history of the city.27 Liverpool was indeed host to people from all over the world, but census statistics suggest the need for caution in estimating their impact on the city’s social fabric. The key elements are shown on table 6. In 1901 only 1.7 per cent of Liverpool’s population had been born outside Britain and Ireland. This was lower than the 2.5 per cent in Manchester and under half the 3.7 per cent of London. Furthermore, the biggest proportion of foreign and empire-born in each city came from mainland Europe, not from overseas, and it ranged from two thirds in Liverpool through three-quarters in London to 84 per cent in Manchester. Foreign sailors were continually coming and going from Liverpool and were part of what Muir described as the ‘amazingly polyglot and cosmopolitan population’.28 Although some came from distant locations, the origin of most sailors tended to be nearer to home. Table 7 shows that on census night in 1881 nearly threequarters of the recorded overseas sailors in Liverpool came from continental Europe, mainly Germany, Scandinavia and Spain.29 In 1911 sailors probably made up about 12 to 15 per cent of the European-born in the city.30 The second body of Europeans in Liverpool was composed of settlers from continental countries excluding Russia and Poland. They were a miscellaneous population, many doubtless a residue of the transmigrants who had passed through the port. Germans were the biggest single group, 1,493 by 1911 and many of them had come to the city in the late-nineteenth century to work in the sugar refineries.31 The third European group was made up of Jewish immigrants, mainly from Russia and Russian Poland. By 1911 the 5,237 Russian empire Jews were much the biggest single group of overseas settlers. They had increased three-fold since 1891. Liverpool’s Jewish community had originated in the mid-eighteenth century and by the 1870s the city had the largest Jewish presence in the provinces – about 2,500 people.32 The flight of Jews from Russian anti-Semitism after 1880 massively increased the number passing through Britain, and Nick Kokosalakis has described Liverpool as ‘a kind of bottleneck’ in the process of emigration.33 During the 1882 pogroms the Liverpool Jewish Board of Guardians assisted over 6,000 transit refugees. East European Jews who settled Table 7 Birthplaces of sailors in Liverpool, 3 April 1881 (10 per cent sample) Birthplace % of total % of overseas sailors Liverpool 20.1 Rest of Great Britain 35.0 Ireland 18.2 Mainland Europe 19.2 72.3 North America 4.7 17.7 Elsewhere overseas 1.8 6.9 At sea/unknown 0.8 3.1 No. 488 130 Source: see note 29 8 augmented the city’s Jewish community, and by 1905 it numbered about 7,000, most of whom had arrived in the previous twenty five years.34 Liverpool’s emigrant trade had therefore played a significant role in changing this element of the city’s social and cultural fabric, but the overall result did not make Liverpool exceptional. Manchester and London’s Jewish communities grew similarly and by the late-nineteenth century both were bigger than that in Liverpool in both sheer numbers and as a proportion of the foreign-born in each city. In 1901 around 30 per cent of Liverpool’s foreign-born, 3,680 people, originated outside Europe and they were split roughly three to one between the British empire and foreign countries. They formed a distinctively higher proportion of the city’s immigrant population than in London or Manchester (table 6) and this reflected Liverpool’s overseas and imperial links. Even so, analysis of enumerators’ returns suggests the need for a certain caution in assessing their contribution to cosmopolitan Liverpool. Comparatively few indigenous people from the empire and foreign countries overseas settled in Liverpool in the nineteenth century. In 1881 there were, for example, 234 people in Liverpool and Toxteth Park whose place of birth was either in ‘India’ or the ‘East Indies’, but at the most only nineteen appear to have been people indigenous to those areas. The overwhelming number, 148 (63 per cent), were ethnically British and fifty-eight, or a quarter, were probably of Irish origin. Many were sometime soldiers, traders and administrators or the wives and children of such people. The imperial background and connections of these Liverpool residents were clearly significant, and would be an interesting subject of research. Even in Frederick Street, which ‘down to the early-twentieth century ….continued to represent the cosmopolitan essence of seaport Liverpool’, most people had been born in Britain or Ireland, though a minority of these were the descendants of immigrants. 35 Under a fifth were continental Europeans and more than a fifth came from overseas (table 8). Liverpool’s black population had originated in the eighteenth century as a direct result of the city’s role in the slave trade. Many came as servants or slaves but others were sent to school in Britain. There were also black soldiers who had fought for the British during the American War of Independence. Sailors from the West Table 8 Frederick Street – birthplaces of people aged over sixteen, 1881 and 1901 Birthplace 1881 1901 % % Britain and Ireland 59.9 61.2 Continental Europe 19.3 15.5 USA/Canada/Aust/NZ 5.2 4.7 West Indies 3.6 1.6 E. Indies/Manilla/China 10.9 15.5 Africa 1.0 1.6 Number of people aged 16+ 192 129 Note: Totals do not equal 100 due to rounding Source: census enumeration returns, Frederick Street, Liverpool, 1881/1901 Indies, Africa and elsewhere nevertheless formed the majority of the city’s AfroCaribbean immigrants in the nineteenth century.36 The black population grew both through the descendants of early settlers as well as by fresh immigration, and has been estimated at around 3,000 in 1911, about 0.4 per cent of the total.37 The concentration of the black population in the South Docks/Park Lane area made it very apparent, but in sheer numbers it was small in relation to the city as a 9 whole. There were concentrations of other overseas and European immigrants in the areas behind the docks like Frederick Street, but, again, their actual numbers were quite small. Liverpool’s minority populations were highly visible in the localities they frequented, and their foreign compatriots who, as sailors, hit town in search of entertainment, drink and women accentuated their apparent presence. Nevertheless, Liverpool’s dominant social character was white and determined by its synthesis of British and Irish peoples. The relatively small numbers of non-white people did not stop elements in the white population exaggerating their significance for their own ends, and this leads John Belchem and Donald MacRaild to argue that Liverpool’s ‘very cosmopolitanism contributed to its propensity to racism’.38 The Chinese were the most obvious group to suffer before 1914. There were very few Chinese in Liverpool before the last decade of the nineteenth century, but from 1892 the Blue Funnel Line began to take on Chinese seamen.39 Some settled in Liverpool, but even by 1911 there were only just over 400 Chinese-born people in the city.40 As Maria Lin Wong says, ‘the Chinese Community in Liverpool remained very small, one might even say minute, for many years.’41 Even so, in the 1900s politicians and white activists stereotyped them as culturally alien cheap labour, and their concentration around Frederick Street, Cleveland Square and Pitt Street made them an easily identifiable target. 42 It is questionable whether, in the nineteenth century, the mixture of immigrants in Liverpool actually created a cosmopolitan culture. Rather, the city was dominated by a fractured white majority from Britain and Ireland amongst whom various continental and overseas minorities inserted themselves. The result was an uneasy mix of peoples with neither hard-edged ghettoes nor a new melting pot cultural synthesis, though there were blended edges as a result of inter-marriage and inter-ethnic relationships. The distinctiveness of Liverpool’s resultant culture and character proved remarkably difficult to define and has continued to be so to the present day.43 Liverpool: a diasporic city? This paper has reinforced the evidence for Liverpool’s pre-eminent role in the worldwide scattering of European peoples in the nineteenth century and surveyed the in-migrant peoples attracted by its dynamic growth, by its worldwide connections or who were a residue from the emigrant traffic. It is this migrant conjuncture that tempts use of the term ‘diasporic city’ for Liverpool, and the concluding section offers some thoughts on this topic. In the last forty years of the twentieth century use of the term ‘diaspora’ broadened from its specific origins in Greek colonisation and the biblical exile of the Jews.44 As a consequence there has been considerable debate about concepts and typologies of diaspora, and at its worst the term is now applied descriptively to any dispersal of peoples, whatever the circumstances.45 In this broad sense Liverpool in the nineteenth century was demonstrably a ‘diasporic space’, a ‘contact zone between different ethnic groups with differing needs and intentions’, but such a statement is essentially descriptive and unhelpful.46 We need to consider whether the experience of Liverpool played an active role in defining, modifying or even destroying peoples’ diasporic identities. Conversely, we need to consider whether diasporic peoples significantly influenced the city’s social, political and cultural life. A minority of self-conscious and articulate groups within a diasporic people may express diasporic identity publicly, but it is always difficult to estimate the 10 strength of diasporic identity amongst a mass of mostly poor migrants. Kevin Kenny has emphasised the need to be wary of evidence from the ethnic press or in popular literature and culture, and the same also applies to associational manifestations of ethnic identity. It may not be representative of the mass but rather of articulate and unrepresentative minorities within it. He suggests the need to consider diasporic groups in terms of a three-fold typology. Firstly there was origin: was the population movement voluntary or involuntary? Secondly, articulation: did members of a dispersed population see themselves in diasporic terms, articulating a sense of common identity amongst themselves as well as with their ‘homelands’? Finally, temporality: how did the group’s experience and self-understanding change over time?47 It is possible to consider the peoples passing through, and settling in, nineteenth-century Liverpool using this typology. The results are inevitably crude since they suffer from two interrelated problems. Firstly, we know very little about how people in the nineteenth century visualised their own identity and their diasporic position. The vast majority of Liverpool’s migrants were poor, often more or less destitute, and they left scant testimony of their feelings and experiences. Secondly, we are forced to apply stereotypical perceptions to these people en masse. These are inherently crude and miss the variations within peoples. The ‘Irish’, for example, are often presented as a monolithic mass but they were actually a diverse ethnic, regional and religious mix, and even amongst the Catholic Irish there was diversity of origins, status, experiences, family strategies and identities. In day-to-day existence, identities amongst diasporic peoples were inevitably contested to a greater or lesser degree. The diasporic identity might count for much or for little but it was always in tension with the countervailing forces of class, religion, status, culture and British nationalism.48 With these provisos in mind, it is possible to consider the potential diasporic status of Liverpool’s various migrant groups in the nineteenth century. In table 9 they have been divided into the emigrants, settlers and transients. The various groups in each class are then considered in terms of Kenny’s three criteria – origins, articulation and temporality. Two other elements have been added. The first, the significance of Liverpool, attempts to estimate the influence contact with Liverpool may have had on the diasporic experience or identity of each group. What role did the city play in the experience or trauma of diasporic movement and settlement? The second considers the migrants’ possible influence on Liverpool’s society, culture and politics. The emigrants are the easiest to consider since for them Liverpool was a brief staging post on a longer journey. The peoples passing through had widely differing degrees of diasporic identity. Whilst other factors may have been at work, voluntary economic migrants made decisions on the relative merits of staying or going in the light of job prospects at home and overseas. Both the British and continental European emigrants (excluding the Jews) were voluntary migrants whose articulation of diasporic identity and connection with an ancestral homeland were weak. The British, the Scandinavians, the Germans and other Europeans ultimately lost any significant diasporic identity and increasingly identified with the emergent social synthesis of their adopted countries.49 This is not to say that they and their descendants gave up all links with their homelands, but, to be historically significant, consciousness of a diasporic inheritance has to define the basic identity, attitudes and behaviour of people down the generations. A folksy interest in culture and family history is not enough. Passage of the British and continental Europeans through Liverpool was historically insignificant for these people and the only imprint they left on the city was as part of its publicly-presented world heritage. The position of Irish emigrants was 11 more complex. Even before the Famine, emigration was borderline between voluntary and involuntary. The Famine crisis, with its evictions and ‘landlord assisted emigration’, was an involuntary expulsion of people. Nevertheless, debates continue as to whether emigration after the Famine should be seen as involuntary exile or as voluntary and purposive movement in search of better prospects.50 It is for this reason that the Irish have been identified as both voluntary and involuntary emigrants in table 9. Transit through Liverpool, particularly until the 1860s, probably had some long-term significance for Irish emigrants. The fraud, squalor and chaos of the Liverpool emigrant trade was a final searing experience of Britain. It was, nevertheless, contradictory since most of those who directly exploited the emigrants were also Irish. Many Irish and their descendants who grew up in America had a diasporic identity defined partly by hostility to Britain and all its works, and memories of Liverpool may have been a minor element in that synthesis. For most Eastern European Jews, on the other hand, Liverpool was a stop on the way to yet more diaspora destinations overseas. Passage through the city had little significance in comparison with the anti-semitism that provoked their move; the Jewish diasporic identity was sustained by far greater traumas. We now come to the characteristics of the groups who settled in nineteenthcentury Liverpool. The majority came from other parts of Britain. Those from England were settling in an English city. Though they may have brought their preindustrial culture and memories with them, they became a dominant part of whatever was the new urban cultural synthesis of Victorian and Edwardian Liverpool. The Scots, Manx and especially the Welsh were from more distinct ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Their diasporic identities were undoubtedly affected by the Liverpool experience and their redefined identities may have contributed to Liverpool’s dynamic cultural synthesis, but more research is needed to define the resultant impacts more effectively. They have been rather overlooked.51 The same cannot be said about the Irish. There has been extensive discussion of the experience of the Catholic Irish in Victorian Liverpool, but little agreement about the nature of their long-term diasporic identity.52 It is popularly supposed that Irish emigrants articulated their diasporic identity strongly and retained a tight, if changing, cultural connection with their homeland. Whilst there is evidence of this, much less is known about those Irish and their descendants, from various backgrounds, whose ties with the home country weakened and who merged more or less willingly into the cultural synthesis of their adopted countries.53 It seems clear that the articulation of Irish identity down the generations was increasingly contested, and weakened, by the pressures of employment, housing and religion, together with local and class-based politics. The Irish had a major influence on Liverpool but, in turn, Liverpool acted on the Irish and their descendants. These are issues recently addressed to some degree in John Belchem’s synthesis of the long-term Catholic Liverpool-Irish experience.54 Articulation of common diasporic identity was clearly strong, though diverse, amongst Liverpool’s Jews and it remained so despite the ultimate dilution of the community through marrying out and migration from Liverpool. Their influence on Liverpool life was limited but in some areas, such as business, noticeable. They contrasted with Liverpool’s non-Jewish immigrants from Europe whose diasporic identity dwindled. They largely merged with the mainstream population after the second generation. It is difficult to generalise about the diasporic identities of Liverpool’s Afro-Caribbean population except to speculate that the sheer diversity of 12 Liverpool’s black peoples must have initially militated against a common articulation. Nevertheless, over time that population as well as its mixed-race descendants increasingly developed a new identity in opposition to the racism it experienced in white Liverpool. The notion of ‘scouseness’ excluded them despite the fact that their roots often lay further back than many of the city’s white immigrants.55 Were Liverpool’s Chinese part of a meaningful diaspora? Only a small community before 1914, they are best classed as part of a voluntary labour diaspora. Their cultural and linguistic apartness initially sustained a continued articulation of diasporic identity, but more research is needed to explore the extent to which that identity was changed by living in Liverpool. Such transformations would largely have occurred beyond the time period covered by this essay. This review of Liverpool’s nineteenth-century immigrants serves primarily to expose the need for a more searching analysis of the significance of diasporic awareness in the various groups making up Liverpool’s population. It is also important to note again that peoples’ diasporic identities were neither fixed nor onedimensional. Their experience in Liverpool was subject to complex pressures and took place within a wider national and world context. It is also impossible to assess whether the diasporic histories of people in Liverpool were exceptional without comparing them in cities elsewhere. As Kenny has argued, ‘a prime subject for historical inquiry is how the diasporic sensibilities of a given migrant people vary according to the places where they reside.’56 The significance of Liverpool’s transient migrants is the final aspect of Liverpool’s diasporic nature to be considered. They went in two directions. Thousands of foreign sailors came into Liverpool, and in a wide definition of diaspora they originated in the voluntary pursuit of work on the sea. They had no particular commitment to the city and their identification remained primarily with the societies from which they came. Liverpool had little influence on them but they may have influenced Liverpool. Their input to the city’s entertainment economy was obvious, whereas their infusion of foreign cultural influences was more intangible but probably longer lasting. More work is needed here. Even more important, perhaps, were Liverpool’s own transient migrants – the sailors and other workers who went overseas but returned to homes, families and associates in the city. There were tens of thousands down the years, and their experience of other countries and cultures must have had a small influence on their own identities and been an element in the city’s evolving culture. Research is needed here also, but we should perhaps be cautious about over-estimating their influence. So was Liverpool a diasporic city in the nineteenth century? This paper has considered its most obvious manifestation in showing that the city played a major role ‘as a sort of highway of emigration’ in the scattering of European peoples.57 It has also suggested that the emigrant trade contributed less to the city’s economy, than might be imagined. It also argues that, in respect of the social impact of immigration, the city exercised little influence on the diasporic identities of the emigrants. British and Irish immigrants were dominant in determining Liverpool’s character and culture and the influence of other groups was marginal, despite the cosmopolitan character they gave to some of the city’s neighbourhoods. In the end it does not seem useful to define nineteenth-century Liverpool generally as a diasporic city. It had a complex and ambiguous identity which reflected interactions and tensions between its various migrant groups, and more comparative work is needed on how these factors influenced the identities of its diasporic peoples. 13 Figure 1 Destinations of passengers from Liverpool, 1825-1913 250000 200000 150000 BNA 100000 50000 Other Aust/NZ 0 18 25 18 28 18 31 18 34 18 37 18 40 18 43 18 46 18 49 18 52 18 55 18 58 18 61 18 64 18 67 18 70 18 73 18 76 18 79 18 82 18 85 18 88 18 91 18 94 18 97 19 00 19 03 19 06 19 09 19 12 Passengers USA For source of data: see footnote 2 14 Years Table 9 Diasporic typology of Liverpool’s nineteenth century peoples Groups Origins Emigrants British Vol Irish Invol/Vol Jewish Largely invol Other European Vol Settlers British Vol Irish Invol/vol Jewish Invol/vol Other European Vol Afro-Caribbean Invol/vol Chinese Vol Transients Abroad→Lpl→abroad Vol Lpl→abroad→Lpl Vol Vol = voluntary; Invol = Involuntary For explanation see text Articulation Diasporic identity over time Significance of Liverpool Influence on Liverpool Weak Strong/weak Strong Weak Lost Weakening Retained but marrying out Lost Nil Some Little Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Mod/weak Strong/weak Strong Weak Strong Strong Largely lost except Welsh? Weakened & transformed →Catholic/class identities? Largely retained but weakening Weakening Retained and/or transformed Retained but some loss? Strong Strong Fairly strong Strong Strong but oppositional Medium Strong Strong Some Some Some Some Strong Strong Irrelevant Irrelevant Weak Strong Some Minimal 15 1 Liverpool Mercury (12 May 1887). The statistics mostly relate to passengers rather than emigrants. Before 1913 no successful distinction was made between emigrants and ordinary cabin passengers. Previous writers have wrestled with the problem of British emigrant statistics, notably I. Ferenczi and W. F. Willcox, International Migrations (New York: National Bureau of Economic Research inc.,1929), Vol. 1, pp. 619-625; N. H. Carrier and J. R. Jeffery, External Migration: A Study of Available Statistics, 1815-1950 (London: HMSO,1953) passim but especially Appendix 2; O. MacDonagh, A Pattern of Government Growth, 1800-1860:The Passenger Acts and their Enforcement (London: McGibbon and Kee, 1961), passim; Brinley Thomas, Migration and Economic Growth (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2nd edn, 1973), chapter 4; J. D. Gould, ‘European Inter-Continental Emigration, 1815-1914: Patterns and Causes’ Journal of European Economic History, 8:3 (1979),. 593-602; D. E. Baines, Migration in a Mature Economy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), pp. 47-54. The port data is from Parliamentary Papers (hereafter PP) as follows:1825-32 – ‘Return of the number of persons who have emigrated from Britain and Ireland, 1825-32’, Report of the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners (1833) 1833-54 – Annual reports of the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners 1855-72 - General reports of the Emigration Commissioners 1876-1913 – Board of Trade returns on emigration and immigration. No port figures have been found for 1836, 1838 and 1873-5; these years are estimated from trends in adjacent years. In the statistics the destination zones identified varied over time and often were not clearly defined. The ‘East Indies’ generally referred to the Indian Empire and south-east Asia. 3 T. Coleman, Passage to America (London: Hutchinson, 1972), pp. 134-37; C. Woodham-Smith, The Great Hunger (London: Hamish Hamilton, New English Library, 1977), pp. 212-32. 4 D. Hollett, Fast Passage to Australia (London: Fairplay, 1986), chapter 11; M. K. Stammers, The Passage Makers (Brighton: Teredo, 1978), pp. 109-18. 5 A. Jackson, ‘Ireland, the Union and the Empire’, in K. Kenny (ed.), Ireland and the British Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 123-53, p. 123. 6 K. Kenny, ‘The Irish in the Empire’, in K. Kenny (ed.), Ireland and the British Empire, pp. 90-122; D. Fitzpatrick, ‘Ireland and the Empire’, in A. Porter (ed.), The Oxford History of the British Empire, Volume III, The Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 494-521; D. H. Akenson, ‘Irish migration to North America, 1800-1920’ and A. Bielenberg, ‘Irish emigration to the British Empire, 1700-1914’, in A. Bielenberg (ed.), The Irish Diaspora (Harlow: Longman, 2000), pp. 111-38 and 215-34. 7 After 1853 there are national statistics on the origin of passengers. The figures on table 3 were produced in three stages. First, the known number of Irish leaving from Irish ports was subtracted from the known number departing from the UK, leaving the total from British ports. It was estimated that 90 per cent left from Liverpool. Second, it was estimated that 90 per cent of the aliens leaving the British Isles also travelled through Liverpool. The resultant totals of transmigrants and Irish were then subtracted 2 16 from the total passengers leaving Liverpool, giving the residue of British emigrants. The estimates are very plausible but should not be seen as numerically definitive. 8 A. Newman, ‘Trains, Shelter and Ships’, unpublished paper presented at Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain seminar, April 2000. 9 Baines, Migration, pp. 77-82. 10 PP, HC1851, Select Committee on the Passenger Act, evidence of William Tapscott, Shipping Agent, Liverpool, Qs. 2740-2819 and George Saul, passenger broker, Q. 3184. 11 Coleman, Passage, chapters 5 and 13. 12 His figures were certainly an underestimate. PP, HC1851, Passenger Act, Q. 2875. 13 PP, HC1857: Session 1 & 2: Return on the number of licenced passage brokers in the Port of Liverpool. 14 PP, HC1851, Passenger Act, Q. 2794. 15 Ibid., Q. 4824. 16 PP, HC1888: XI:419, Select Committee on Emigration and Immigration (Foreigners), Henry Joseph Hagger, Vestry Clerk, Parish of Liverpool, paras. 314320. 17 The Times (28 and 29 September 1892). 18 Evans, Indirect Passage: G. O. Holt, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume X :The North West (Newton Abbott: David and Charles, 1978), p. 55. 19 F. E. Hyde, Liverpool and the Mersey (Newton Abbott: David and Charles, 1971) p. 114; R. Bastin, ‘Cunard and the Liverpool emigrant traffic’, (MA dissertation, University of Liverpool, 1971), p.132. 20 Hyde, Liverpool and the Mersey, p. 124; G. J. Milne, ‘Maritime Liverpool’, in J. Belchem (ed.), Liverpool 800: Culture, Character and History (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2006), pp. 274-80. 21 A. J. Maginnis, The Atlantic Ferry: Its Ships, Men and Working (London: Whittaker and Co., 1900), pp. 24-118. 22 Bastin, ‘Cunard’, chapter 5. 23 The table uses quoted steerage fares from various secondary and primary sources, as follows: 1825-30: £3; 1830-39: £3 10s; 1840-45: £4; 1846-53: £6; 1854-59: £4 5s; 1860-73: £6 6s; 1874-82: £5; 1883-89: £4 4s; 1890-99: £5; 1900-05: £3; 1906-13: £5. The totals of passengers to USA and Canada have been multiplied by these fares. No allowance is made for children or for cabin passengers paying higher fares; they may cancel each other out. 24 See J. Belchem, ‘Class, creed and country: the Irish middle class in Victorian Liverpool’, in R. Swift and S. Gilley (eds), The Irish in Victorian Britain: The Local Dimension (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1999), pp. 190-211. 25 Jackson, ‘Ireland, the Union and the Empire’, p. 124. 26 In his well known book Pat O’Mara illustrated the complexities of this identity in 1900s Liverpool. His own background was three-quarters Irish. He was ‘sternly Irishized’ at home but developed ‘an intense love for the British Empire and an equally intense hatred for England’ through his Catholic ‘English-Irish schooling’. P. O’Mara, The Autobiography of a Liverpool Slummy (Liverpool: Bluecoat Press, 1995), pp. 56-7. 27 Ramsey Muir, A History of Liverpool (London: Williams and Norgate, 1907), p. 304. J. Belchem and D. M. MacRaild, ‘Cosmopolitan Liverpool’, in Belchem, Liverpool 800, chapter 5, esp., p. 320. 28 Muir, Liverpool, p. 305. 17 A 10 per cent systematic sample was taken of all ‘sailors’, ‘seamen’ and ‘mariners’ in the Liverpool Borough enumeration returns including 10 per cent of all people (apart from passengers) on vessels in port and in the Sailors’ Home, Canning Place. The census probably under-recorded transient sailors in brothels and drinking dens, but there is no reason to think the proportions of different nationalities were distorted. 30 Given that Manchester had more European immigrants than Liverpool (13,104 to 9,775 in 1911), it has been assumed that in those countries which had more representatives in Liverpool than Manchester the surplus consisted of sailors. There was an excess of 1,184 from such countries in 1911, 12.1% of the European total. 31 PP, HC1888, X.265, Select Committee on emigration, Hagger evidence , para. 292. 32 N. Kokosalakis, Ethnic Identity and Religion: Tradition and Change in Liverpool Jewry (Washington: University Press of America, 1982), pp. 43-4, 50-1, 154. 33 Ibid., p. 99. 34 Ibid., p. 154. 35 Belchem and MacRaild, ‘Cosmopolitan Liverpool’, p. 318. 36 R. Costello, Black Liverpool: The Early History of Britain’s Oldest Black Community, 1730-1918 (Liverpool: Picton, 2001), pp. 8-19. 37 I. Law and J. Henfrey, A History of Race and Racism in Liverpool, 1660-1950 (Liverpool: Merseyside Community Relations Council, 1981), pp. 15, 25; Costello, Black Liverpool, p. 69. 38 Belchem and MacRaild, ‘Cosmopolitan Liverpool’, p. 320. 39 M.L. Wong, Chinese Liverpudlians: The History of the Chinese Community in Liverpool (Birkenhead: Liver Press, 1989), pp. 4-6. 40 A further 268 people were born in ‘Other Colonies in Asia’. Some may have been Chinese from Hong Kong and other places in the British empire. If all these are assumed to have been Chinese, which is unlikely, the Chinese total was no more than 672. 41 Wong, Chinese, p. 8. 42 P. J. Waller, Democracy and Sectarianism: A Social and Political History of Liverpool, 1868-1939 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1981) pp. 217, 220, 224-6. 43 The themes of cosmopolitanism, exceptionalism and distinctiveness run through Belchem (ed.), Liverpool 800, notably in chapters three and five, but the precise nature of the Liverpool’s distinctive synthesis remains elusive. 44 R. Cohen, Global Diasporas (London: University College of London Press, 1997), p. 2. 45 Ibid., is the best overall summary. 46 Belchem, Liverpool 800, p. 14. 47 K. Kenny, ‘Diaspora and comparison: the global Irish as a case study’, Journal of American History, 90:1 (June 2003), pp. 134-62, (e-version on http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jah/90.1/kenny.html, pp. 4-6, accessed 26 November 2003.) 48 S. Fielding, Class and Identity: Irish Catholics in England, 1880-1939 (Buckingham: Open University Press, 1993), pp. 10-18. 49 The Scottish victims of the Highland Clearances were also ‘involuntary’ emigrants. There are probably continental exceptions too. 50 See the perspectives of Kerby Miller and Donald Akenson. K. Miller, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America (New York: Oxford 29 18 University Press,1985); D. H. Akenson, The Irish Diaspora: A Primer (Toronto: P. D. Meany Company Inc., 1993). 51 Belchem and MacRaild present vignettes of Liverpool’s Welsh, Scots and Manx peoples which cover their more obvious cultural and social manifestations. Belchem and MacRaild, ‘Cosmopolitan Liverpool’, pp. 344-58. 52 Belchem’s Merseypride argues for the continuing apartness of the ‘Irish Catholic enclave’ in Liverpool. This contrasts with work arguing for increasing integration such as C. Pooley, ‘Segregation or integration? The residential experience of the Irish in mid-Victorian Britain’, in R. Swift and S. Gilley (eds), The Irish in Britain, 18151939 (London: Pinter Publishers, 1989), pp 61-81. 53 Two studies with oral and family history evidence are: R. Byron, Irish America (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999) and J. Herson, ‘Family history and memory in Irish immigrant families’ in K. Burrell and P. Panayi (eds), Histories and Memories: Migrants and their History in Britain (London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2006), pp. 210-233. 54 J. Belchem, Irish, Catholic and Scouse: the History of the Liverpool-Irish, 18001939, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007). 55 D. Frost, ‘West Africans, Black Scousers and the colour problem in Inter-War Liverpool’, North-West Labour History, 20 (1995-6), pp. 50-57, p. 56. Belchem and MacRaild, ‘Cosmopolitan Liverpool’, pp. 368-88. 56 Kenny, ‘Diaspora and comparison’, p. 19. 57 The comment was made by Herman John Falk, a German industrialist in the Cheshire salt trade, in 1888. PP, HC1888, Select Committee on emigration, para. 3478. 19