Writing Analytically, Chap 4, “Reading: How to Do It and What to Do

advertisement

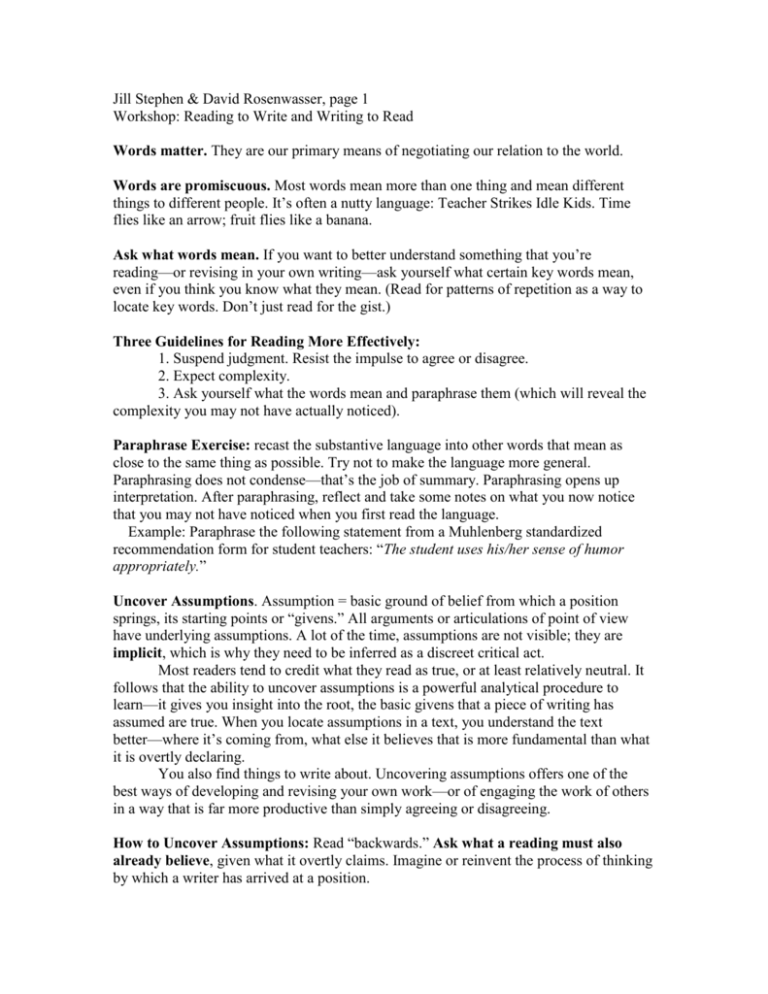

Jill Stephen & David Rosenwasser, page 1 Workshop: Reading to Write and Writing to Read Words matter. They are our primary means of negotiating our relation to the world. Words are promiscuous. Most words mean more than one thing and mean different things to different people. It’s often a nutty language: Teacher Strikes Idle Kids. Time flies like an arrow; fruit flies like a banana. Ask what words mean. If you want to better understand something that you’re reading—or revising in your own writing—ask yourself what certain key words mean, even if you think you know what they mean. (Read for patterns of repetition as a way to locate key words. Don’t just read for the gist.) Three Guidelines for Reading More Effectively: 1. Suspend judgment. Resist the impulse to agree or disagree. 2. Expect complexity. 3. Ask yourself what the words mean and paraphrase them (which will reveal the complexity you may not have actually noticed). Paraphrase Exercise: recast the substantive language into other words that mean as close to the same thing as possible. Try not to make the language more general. Paraphrasing does not condense—that’s the job of summary. Paraphrasing opens up interpretation. After paraphrasing, reflect and take some notes on what you now notice that you may not have noticed when you first read the language. Example: Paraphrase the following statement from a Muhlenberg standardized recommendation form for student teachers: “The student uses his/her sense of humor appropriately.” Uncover Assumptions. Assumption = basic ground of belief from which a position springs, its starting points or “givens.” All arguments or articulations of point of view have underlying assumptions. A lot of the time, assumptions are not visible; they are implicit, which is why they need to be inferred as a discreet critical act. Most readers tend to credit what they read as true, or at least relatively neutral. It follows that the ability to uncover assumptions is a powerful analytical procedure to learn—it gives you insight into the root, the basic givens that a piece of writing has assumed are true. When you locate assumptions in a text, you understand the text better—where it’s coming from, what else it believes that is more fundamental than what it is overtly declaring. You also find things to write about. Uncovering assumptions offers one of the best ways of developing and revising your own work—or of engaging the work of others in a way that is far more productive than simply agreeing or disagreeing. How to Uncover Assumptions: Read “backwards.” Ask what a reading must also already believe, given what it overtly claims. Imagine or reinvent the process of thinking by which a writer has arrived at a position. Stephen & Rosenwasser, page 2 Workshop: Reading to Write and Writing to Read After you have paraphrased the explicit claim, list implicit ideas that the claim assumes to be true. These will have to be inferred because they are not stated directly. Note: it is often helpful to try on an oppositional stance to the claim—because understanding what the claim is not saying will often help you to recognize underlying assumptions that it is “saying.” Uncovering Assumptions Exercise: What must the writers of the recommendation form who asked that student teachers be evaluated in regard to “The student uses his/her sense of humor appropriately” also already believe? List these assumptions. Another Exercise: Uncover the assumptions in the following: “Telling others about oneself is, then, no simple matter. It depends on what we think they think we ought to be like—or what selves in general ought to be like” (Jerome Bruner, Making Stories: Law, Literature, Life). Useful homework assignment: Locate a statement from the reading that you find interesting, challenging, etc. Paraphrase it. Then uncover assumptions, asking what must the text also already believe, given that it believes this? List at least three. Find the Problem: Virtually all writing can be seen as trying to address some (often unstated) problem or problems. Writers write because they have determined that something needs to be done to correct our understanding of some idea or situation. You can read more actively by trying to figure out from the language of the reading what its author is worried about and what he or she is trying to “fix.” This is true even of textbooks: informational reading still has a point of view. Whenever you can, find the position that the reading is trying to resist, revise, or replace. How to Find the Problem: Attend to the complaint and the pitch (aka, more rudely, “the bitch and the pitch). Look for language that reveals the position or positions the piece seems interested in having you adopt. It is easier to find the pitch if you first look for language that reveals the position or situation the writer is trying to correct. At root here is an orientation towards reading that assumes that information is virtually never neutral. Doing Things with Reading Apply a Reading as a Lens; Avoid the Matching Exercise. The big problem with the way most people apply a reading is that they do so too indiscriminately, too generally. They essentially construct a matching exercise in which each of a set of ideas drawn from Stephen & Rosenwasser, page 3 Workshop: Reading to Write and Writing to Read Text A is made to equate with a corresponding element from Subject B in virtual list-like fashion. Often Text A is a theory used very mechanically to explain Example B. How to Apply a Reading as a Lens. Assume that the match between Lens A and Subject B won’t be exact. Think about how A both fits and does not fit B. Move Beyond Basic Similarity. Too often readers notice a fundamental similarity and stop there. But ideas tend to arise when readers move beyond this basic demonstration and complicate (or “qualify”) the basic similarity by also noting areas of difference, and accounting for the significance of that difference. Procedure: Identify fundamental similarity. Account for its significance by answering the question, “so what that they have this similarity?” Then, given the similarity, locate the most important difference, and repeat the “so what?” Hint: When A and B are obviously different, look for unexpected similarity. When A and B are obviously similar, look for unexpected difference.