tangled histories - Shifting Borders of Race and Identity

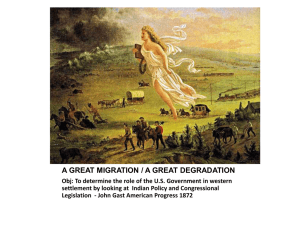

advertisement