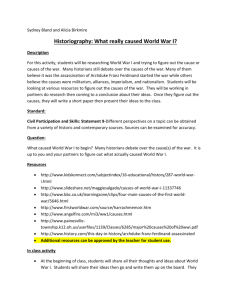

Historical Research in Education

advertisement