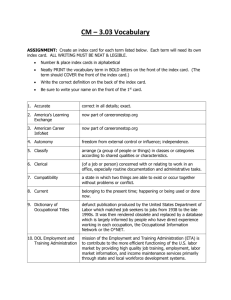

Versions of Dictionary of Occupational Titles

advertisement

Measuring Occupational Conditions: Using the Dictionary of Occupational Titles and the Census Occupational Coding Systems (Menaghan, 08/01 Background. The original purpose of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT) was for use by Employment Services offices to evaluate the fit between worker and occupation. Therefore, many of the DOT variables are expressed in terms of necessary or desirable characteristics (aptitudes, temperament, and interests) of the worker. But these implicitly describe what the occupation requires. The 4th Edition of the DOT scores 12,099 occupations (each of which gets a nine-digit DOT code) on 44-46 variables that fall into seven clusters: work functions (n = 3: re complexity of work with data, people, things) education and training required (n = 2-4; education rating is sometimes split into 3, to make a total of 4) aptitudes needed (n = 11) temperaments needed (measured as dichotomies, n = 10) interests (interested more in X than Y, n = 5) physical demands (n = 6) working conditions in the environment (n = 7) Two major obstacles to use of the DOT measures in research are the need to translate them into differing occupational coding systems, and questions about data quality. Obstacle 1. Need to translate DOT occupational codes into other occupational coding systems used. Most surveys do not code to such a detailed occupational classification as the DOT, which distinguishes over 12,000 occupations. They typically use a version of the 3-digit occupational classifications of the U.S. Census (or other schemes). This has been done! 1970: 4th Ed. DOT codes have been mapped to 1970 Census occ codes (the expanded list of 591 occ/industry codes), by Roos and Treiman, in Miller et al 1980 book published by the National Academy Press. Appendix F of the Miller et al 1980 book contains values for some DOT measures for the 1970 expanded list of occupational codes. Appendix F notes that some of the 1970 occupational codes did not occur in the April 1971 Current Population Survey used to do this mapping, resulting in 18 Census codes having missing data. All but one of these (580, former member of the Armed Forces) were assigned DOT values for a closely related occupation. Appendix F-3 describes the decision rules used to assign values from other occupations to these. 1980: 4th edition DOT has been mapped to 1980 Census occupational codes (N = 503 occupational categories) by England and Kilbourne, 1988. This data set is available from IUCPSR. Obstacle 2. Data quality. Miller et al’s 1980 book, chapter 7, identifies many problems with the data collection and measurement of the 4th Edition DOT items. Despite these problems, Miller et al conclude that the DOT is still the best information available. 2 Scholars have therefore tried to develop a smaller set of more reliable and meaningful scales by factor-analyzing these variables. Efforts to develop factor scales or factor-based scales from the 4th edition DOT for 1977 DOT codes and for 1960, 1970, and 1980 Census occupational codes. Overview: There have been a number of such factor analyses of 4th edition DOT data. One influential analysis (Cain and Treiman, 1981) used DOT occupations as the unit of analysis, but the others have used one or the other version of Census occupations. Typically, the first factor that emerges captures the complexity/higher cognitive demands of the occupation. Others distinguish need for fine motor skills, need for more “brawn/agility,” and exposure to more adverse physical work environments. Some but not all solutions identify a factor or factors describing skills associated with interaction, sometimes distinguishing leadership/authority from more general dealing with people. These “social” factors have been variously labeled management skills, authority/supervisory skill, leadership skill; and social skills, interpersonal skills, dealing with people more than things, nurturant skills. Most solutions have forced orthogonality, but some have permitted factors to co-vary. Most have tried to find a simple solution (with few items loading on more than one factor). In order of their publication, these factor analyses include the following detailed reports of results: 1. Cain, chapter 7 in Miller et al 1980 10 percent sample of DOT occupations (also reported in Cain and Treiman, 1981 article) 2. Ross and Treiman, in Miller et al 1980 1970 Census occupations 3. Parcel chapter, in Michael, ed. 1989 1980 Census occupations 4. Kilbourne et al article 1994 1960 Census occupations 5. Shu, Fan, Li, and Marini article 1996 1960, 1970, & 1980 Census occupations. Here I report only the first factor scores published by Miller et al , and the final factors discussed by Shu. 1. In appendix F of the 1980 Miller et al volume, Roos and Treiman report a factoranalysis of DOT data aggregated to the expanded set of 591 1970 Census codes. This used principal components and orthogonal (varimax) rotation. Their suggested factors included only items that BOTH had a .5 or larger loading on the primary factor AND did not load .3 or larger on any other factor. They identify four factors: 1) Substantive Complexity (8 items: higher complexity with data; higher GED and SVP; Aptitudes for Intell, Verbal, Numer; Interest in more abstract/less routine, concrete activities; and low temperament for repetitious/continuous work.) 2) Motor Skills (6 items: higher complexity with things; Aptitudes for motor, finger dexterity, manual dexterity, and color discrimination; and Physical demand for seeing) 3 3) Physical Demands (5 items: Aptitudes for eye-hand coordination; Demands for climbing, for stooping; and Working Conditions, outdoor location and hazards; and 6) Undesirable Working Conditions (3 items, Working Conditions, exposure to extreme heat, cold, wet/humid conditions). 22 of the DOT items are not included on any of these factors. They compute scores for these four scales by standardizing the DOT items, summing the items, and then transforming the scales so they range from 0 to 10. These scores are reported in Table F-2 for the expanded set of 591 1970 Census occupational codes. In Table F-1 they report (for the same expanded set of 1970 Census occupational codes) the values for six of the original DOT items: complexity of work with data, with people, and with things; general educational development (GED) needed; specific vocational training (years needed to learn the tasks of the occupation; and strength needed. On the same table they also report the values for two additional composites: a) number of physical demands: ranges from 0 to 4, climbing; stooping; reaching; seeing; b) b) number of harsh environmental conditions existing on the job: ranges from 0 to 6, extreme cold; extreme heat; wet and/or humid; noise and/or vibration; hazards; atmosphere (poor air quality: fumes, odors, dust, gases, poor ventilation). 1. 2. Shu, Fan, Li, and Marini, 1996 (Social Science Research article). They factor- analyze DOT data linked to the 1960, 1970 and 1980 Census occupational codes; they use confirmatory factor analysis with latent constructs and permit constructs to be intercorrelated. They hypothesized seven factors; they subsequently dropped one of these, “Leadership,” which they intended to tap an administrative and supervisory dimension of occupations. No item loads on more than one factor. The six scales use 31 of the DOT measures. Of the 13 not used, five DOT variables were excluded because of low correlations or low variation; five more were subsequently excluded because of low factor loadings, and three more were dropped when the hypothesized factor they loaded on (leadership) was dropped. They report that estimates for the three Census years are highly similar. Their factors (see their Table 4, p. 165): 1. substantive complexity (8 items: complexity with data; GED, SVP; aptitudes for intelligence, verbal, numerical; low on interest in repetitious/continuous activity; preference for more abstract/less concrete routine activity)(this factor is identical to Roos/Treiman substantive complexity factor reported in Miller, Appendix F) 2a. motor skill (4 items: complexity with things; aptitudes for motor coordination, for finger dexterity, for manual dexterity) 2b. physical perception (3 items: aptitudes for spatial perception, for form perception, for color discrimination) ¾. social skill (6 items, no overlap with factor 1:complexity of tasks with people; temperament for dealing with people, temperament for influencing people; interests in more communication of data/less activities with things; interests in more social welfare/less activities involving processes, machines; and demand for talking/hearing 4 5. physical demands (5 items): aptitude for eye-hand-foot coordination; demands for climbing, stooping, reaching; more outdoor location 6. working conditions (5 items) –note scored higher equals more pleasant: exposure to heat, cold, noise, hazards, and poor air quality). They note that factors 1(substantive complexity), 3/4 (social skill) and 6 (more pleasant working conditions) are correlated, and all three are inversely related to 5, the physical demands of an occupation; they state that these correlations are consistent with our knowledge of relationships among occupational characteristics in the U. S. labor force. These factor scores, for all three sets of Census codes (1960, 1970, and 1980) are available from the authors (see article footnote 9). Other measures of occupational conditions developed: Kilbourne et al 1994 AJS create a dummy variable for nurturant skills. This is coded “1” if each of two criteria were met: the occupation requires providing a service while engaged in face-to-face contact with clients or customers, AND this providing of service occurs during a substnatial portion of work time…”All these occupations require intense interaction with clients, students, or patients. Many occupations scoring high require one to empathize with others so as to discern their needs while managing one’s own emotions” (p. 717). England coded this variable; a second rater’s coding (not used to construct the measure) produced an inter-rater reliability of .7. See p. 716 for a list of 1960 Census occupational titles that were coded as nurturant. This measure was standardized and added to two 4th Ed. DOT items, temperament for dealing with people, and demands for talking/hearing, to construct their composite measure of nurturant social skill. They have also coded this for 1980 Census occupations. They find that occupations coded 1 have lower average hourly earnings, for both men and women. Authority. See England, Herbert, Kilbourne, Reid, and Megdal, 1994 Social Forces article use 1980 Census occupational codes (n= 503). Here, they describe the authority measure as coded 1 for all occupations with the word manager, supervisor, or administration in the title. They included lower, middle, and upper levels of management in both the public, private, and nonprofit sectors as well as foremen and other supervisors of blue-collar workers” (p. 76). See Table 2, p. 75 for list of 1980 Census occupations coded as involving authority.: Note re CHRR Census occ codes: Depending on the cohort and the survey year, the CHRR codes occupations with 1960, 1970, 1980, and 1990 codes. So, the occupational codes available to the researcher vary depending on the research question and study population. For the NLSY1979 Youth cohort and its associated Child-Mother dataset, the 1970 occupational codes are the ones most commonly used (see chart). The CHRR list of 1970 Census occupational codes includes 423 rather than 428 1970 occupations: it does not use codes 281, 282, 283, 284, 285, which are all varieties of sales occupations. 5 References Cain, Pamela. 1980. "An Assessment of The Dictionary of Occupational Titles as a Source of Occupational Information." Pp. 148-197 in Work, Jobs, and Occupations : A Critical Review of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, edited by A. R. Miller, D. T. Treiman, P. S. Cain, and P. A. Roos. Committee on Occupational Classification and Analysis, Assembly of Behavioral and Social Sciences, National Research Council Washington, D.C., National Academy Press. Cain, Pamela and Donald Treiman. 1981. "The Dictionary of Occupational Titles as a Source of Occupational Data." American Sociological Review 46: (3) 253-278. Daymont, Thomas and Ronald D'Amico. 1979. "Dictionary of Occupational Titles Variables for 1960 Occupational Titles." (MDRF). Center for Human Resource Research, Ohio State University (producer and distributor). Elliott, Marta and Toby Parcel. 1996. "The Determinants of Young Women's Wages: Career Disruption Effects on Early Wages: Comparing the Effects of Individual and Occupational Labor Market Characteristics." Social Science Research 25 (3): 240-259. England, Paula. 1992. Comparable Worth: Theories and Evidence. Walter de Gruyter, New York: Aldine de Gruyter. England, Paula, Melissa Herbert, Barbara Stanek Kilbourne, Lori Reid, and Lori McCreary Megdal. 1994. "The Gendered Valuation of Occupations and Skills: Earnings in 1980 Census Occupations." Social Forces 73(1): 65-99. England, Paula, Barbara Stanek Kilbourne, and George Farkas. 1988. "Explaining Occupational Sex Segregation and Wages: Findings from a Model with Fixed Effects." American Sociological Review 53(4): 544-558. Farkas, George, Paula England, Keven Vicknair, and Barbara Stanek Kilbourne. 1997. "Cognitive Skill, Skill Demands of Jobs, and Earnings Among Young European American, African American and Mexican American Workers." Social Forces 75(3): 913-940. Kilbourne Barbara Stanek, Paula England, and Kurt Beron. 1994. "Effects of Individual, Occupational, and Industrial Characteristics on Earnings: Intersections of Race and Gender." Social Forces 72 (4): 1149-1176. Kilbourne Barbara Stanek, Paula England, George Farkas, Kurt Beron, and Dorthea Weir. 1994. "Returns to Skill, Compensating Differentials, and Gender Bias: Effects of Occupational Characteristics on the Wages of White Women and Men." American Journal of Sociology 100 (3): 689-719. 6 Link, Bruce, Mary Clare Lennon and Bruce Dohrenwend. 1993. "Socioeconomic Status and Depression: The Role of Occupations Involving Direction, Control, and Planning." American Journal of Sociology 98(6): 1351-1387. Miller, Ann, Donald Treiman, Pamela Cain, and Patricia Roos. 1980. Work, Jobs, and Occupations : A Critical Review of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles. Committee on Occupational Classification and Analysis, Assembly of Behavioral and Social Sciences, National Research Council Washington, D.C. : National Academy Press. Parcel, Toby. 1989. "Comparable Worth, Occupational Labor Markets, and Occupational Earnings: Results from the 1980 Census." Pp. 134-152 in Pay Equity: Empirical Inquiries, edited by Robert T. Michael, Washington D.C.: National Academy Press. Parcel, Toby and Charles Mueller. 1983. "Occupational Differentiation, Prestige, and Socioeconomic Status." Work and Occupations 10(1): 49-80. Parcel, Toby and Charles W. Mueller. 1983. Ascription and Labor Markets: Race and Sex Differences in Earnings. New York: Academic Press. Parcel, Toby and Charles Mueller. 1989. "Temporal Changes in Occupational Earnings Attainment, 1970-1980." American Sociological Review 54(4): 622-634. Rogers Stacy, Toby Parcel, and Elizabeth Menaghan. 1991. "The Effects of Maternal Working-Conditions and Mastery on Child-Behavior Problems: Studying the Intergenerational Transmission of Social-Control." Journal of Health and Social Behavior 32(2): 145-164. Roos, Patricia and Donald Treiman. 1980. "Appendix F: DOT Scales for the 1970 Census Classification." Pp. 336-389 in Work, Jobs, and Occupations : A Critical Review of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, edited by A. R. Miller, D. J. Treiman, P. S. Cain, and P. A. Roos, Committee on Occupational Classification and Analysis, Assembly of Behavioral and Social Sciences, National Research Council, Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. Shu Xiaoling, PiLing Fan, Xiaoli Li, and Margaret Marini. 1996. "Characterizing Occupations With Data From the Dictionary of Occupational Titles." Social Science Research 25 (2): 149-173. 7 Notes re past and future: Of historical interest only at this point: 3rd Ed DOT codes were aggregated to 1960 or 1970 Census occ codes, for some or all DOT variables, by Lucas (1974), Temme (1975), Spenner (1980). These data have been used by these and other scholars, including Parcel and Mueller’s 1983 book and their 1983 Work and Occupations article (this article says Spenner provided the DOT data they used). Matching 4th edition DOT measures to 1990 Census occupational codes: No work on this problem has been located. Since the new NLSY97 youth cohort of adolescents 12-17 codes occupations only with the 1990 Census occupational codes, this means it is not yet possible to associate DOT data with those occupations. Census Occ codes versus SOC codes: The CHRR list of 1980 Census codes also includes the matching 1977 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) code equivalents. The SOC coding scheme is the one used by the US Department of Commerce, and its 1998 revision appears to be becoming the new standard. The 2000 Census will code occupations using the 1998 revision to the Standard Occupational Classification, SOC; this distinguishes 749 occupations. This 1998 revised SOC occupational classification system is supposed to be phased in by all federal agencies in 2000-2002, and it is what will be linked to the O*NET (which is intended to supersede all editions of the DOT). References to Publications mentioned in pp. 1-9 of this document: Miller et al book Cain Cain and Treiman England and Kilbourne 1988 Shu et all ssr 1996 Kilbourne, Enlgand, and Beron SF 1994 Kilbourne, England, Farkas, Beron, and Weir AJS 1994 Roos and Treiman appendix F Parcel and Mueller asr 1989 Brown 1990 thesis (locate subsequent publication) Parcel 1989 chapter Farkas, England, Vicknair, and Kilbourne SF 1997 Rogers, Parcel, and Menaghan jhsb 1991 England, Herbert, Kilbourne, Reid, and Megdal SF 1994 Others? Check against document..