Module: Diffusion of fluids within porous materials, NMR part II.

advertisement

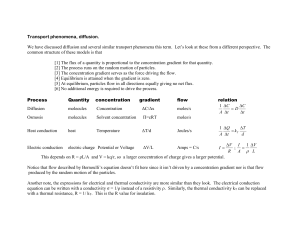

KJM-MEF4010 - Eksperimentelle metoder Module: Diffusion of fluids within porous materials, NMR part II. (Water confined between glass beads) Eddy W. Hansen UiO, February 2005 Introduction Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) represents a notable tool to characterize molecular dynamics within both solid and liquid samples. In this project we will concentrate on spin-spin relaxation time (T2), spin-lattice relaxation time (T1) and diffusion (D) measurements of water confined within small glass beads with the object to characterize the molecular dynamics of pore-confined water. In general, NMR is capable of pinning down details regarding motional characteristics of any fluid confined in porous materials like; catalytic materials (zeolites and mesoporous materials), sandstone, clay, wood, plants and biological materials (like the human body). Also, the interaction between the fluid molecules and the molecules belonging to the solid surface may be probed by this spectroscopic. Although a large fraction of the nuclei in the periodic table are NMR active, only the proton nucleus will be amenable for detection in this project. The outlined theory will, however, be of general validity. Activities Lectures (approximately 2-3 hours) and laboratory work (under supervision) Teaching material Distributed at the first lecture Time schedule 2 weeks (31.03 – 13.04) Objects To understand the concept of relaxation and diffusion from a phenomenological point of view (Bloch equations) To be able to perform relaxation and diffusion measurements To derive information on diffusivity, surface-to-volume-ratio and surface-fluid interaction by model fitting (using PC) To understand the additional complexity involved in analyzing NMR data from pore-confined fluids, as compared to bulk fluids. To recognize the applicability of NMR in varies aspects of material science. 1 Introduction Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) represents a notable tool in characterizing molecular dynamics within both solids and liquids. In this project we will concentrate on the measurement of relaxation times (T1 and T2) and diffusivity (D) of water confined between small glass beads aiming at elucidating the molecular dynamics of pore-confined water. In general, NMR is capable of detailing the motional characteristics of any fluid confined in porous materials like; catalytic materials (zeolites and mesoporous materials), sandstone, clay, wood, plants and biological materials (“human body”). Also, the strength of the molecular interaction between fluid molecules and pore surface molecules of the matrix can be probed, as well. A second object with the project is to present a brief outline of the NMR theory, via the Bloch equation concept, and to give the student some practical NMR experience. Hopefully, the student will realize the potential of the NMR spectroscopic technique in various areas of material science research. Although a large fraction of the nuclei in the periodic table are NMR active, the proton nucleus will be the only probe molecule considered in this project. The theoretical outline will, however, be of general validity. Theory As pointed out in the introductory section, most of the nuclei in the periodic table possess a magnetic moment (). For a proton nucleus, its magnetic moment will orient either parallel or anti-parallel to an external magnetic field B0. At thermal equilibrium, a surplus of the proton nuclei within a sample will have their magnetic moments oriented parallel to the static magnetic field B0 and hence generate a macroscopic magnetic moment M0 aligned parallel to the static field B0, as illustrated in Fig.1A. Figure 1A. At equilibrium the macroscopic magnetization M0 is aligned parallel to the static magnetic field B0. B) If applying an rf-pulse B1 of duration tp along the x-axis, the macroscopic magnetization will rotate by an angle = B1tp around this axis. Since the detector coil is aligned normal (y-axis) to the external magnetic field B0, no signal will be detected (Figure 1A), since the macroscopic magnetization has no component along this axis. In order to detect a signal the macroscopic magnetization must be tilted away from the z-axis, as illustrated in Figure 1B. Such a re-orientation, or rotation of the magnetization is performed by irradiating the sample with a radio 2 frequency (rf) pulse of duration tp and magnitude B1. The single pulse sequence and the resulting time signal are illustrated in Figure 2. Figure 2. NMR signal intensity against time (along the y-axis) after application of an rfpulse Fig.3 shows the actual signal response from bulk water after application of an rf-pulse of duration 2.15 s, which corresponds to a tip-angle of 900,i.e., the macroscopic magnetization is rotated 900 - relative to the z-axis - and onto the y-axis. Figure 3. Proton NMR signal (Free Induction Decay) of bulk water after applying a /2 rf-pulse. The red curve represents a single-exponential fit to the data. Bloch equations How the macroscopic magnetization ( M M x i M y j M z k ) depends on time can be described phenomenological by the following vector equation (Bloch equation); My M M M0 M M xB x i j z k D 2 M t T2 T2 T1 (1a) 3 where B represents external magnetic fields as well as rf-pulses, D is the self-diffusion coefficient and 2 2 / x 2 / y 2 / z . These equations reveal two independent signals to appear in an NMR experiment; a transversal magnetization Mx(y) decaying with rate constant 1/T2 and a longitudinal magnetization Mz(t) which increases asymptotically with time at a rate constant 1/T1. T1 and T2 define the spin-lattice relaxation time and the spin-spin relaxation time, respectively. Free Induction Decay (FID) If excluding the diffusion term (D = 0) a /2 rf-pulse (B1) along the x-axis will rotate the magnetization into the y-axis (My), after which it must obey the Bloch equation under the constraint that B = 0 i.e.; dM y dt My (1b) T2' showing that My will decay with a rate constant 1/T’2.. The explicit solution to Eq. 1b reads; M y M 0 exp t / T2' (2) The solid (red) curve in Figure 3 represents a non-linear least squares fit to Eq 2 with T’2 = 1.5s. As will become clearer later T’2 does not necessarily reflect the true spin-spin relaxation time T2. T1-measurement If applying an rf-pulse which inverts the longitudinal magnetization (-pulse), i.e., Mz = M0, the time behavior of this longitudinal magnetization Mz(t) can easily be determined by simple integration of Eq. 1a with respect to time; Mz M 0 t dM ' z dt M 0 M ' z 0 T1 M z M 0 1 2e t / T1 (3) The experimental approach to determine T1 is thus to apply the following pulse sequence; Figure 4. Schematic view of the inversion recovery pulse sequence used to measure T1. 4 in which the longitudinal magnetization is measured at various times t = t1. For a given t1, the pulse sequence is repeated a finite number of times (number of scans) in order to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (Figure 5). The time delay tR between each inversion sequence should be chosen so that tR > 5*T1. Figure 5. A series of inversion recovery pulse sequences, with a time delay tR between the read pulse (/2-pulse) in one sequence and the inversion pulse in the next sequence. Figure 6 shows the results of an inversion recovery experiment (T1 experiment) applied to bulk water. The circles represent the longitudinal magnetization at different times, t1. Figure 6. Inversion recovery data of bulk water recorded at different inversion times t1 (Figure 5) with tR set equal to 15s. The red curve represents a non linear least squares fit to Eq 3 with T1 = (3315 + 50) ms. The blue curve represents the residuals. Exercise 1; Measure T1 of water confined in glass beads and discuss the results with respect to a “two-phases in fast exchange”-model (see appendix A). Determine F1 = T1,pore-water/T1,bulk-water. What does this parameter tell you about the fluid-surface interaction? T2-measurement As can be inferred from the data shown in Figures 3 and 6, T1 is significantly larger than T’2. For distilled water containing no oxygen these relaxation times are expected to be identical. The reason for T’2 being smaller than T1 originates from a combined effect of magnetic field inhomogeneities within the sample and molecular diffusion. The effect of the former can be circumvented by applying a train of -pulses, as illustrated in Figure 7. 5 Figure 7. A train of spin-echo pulses illustrating the Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill-pulse sequence (CPMG). The expression for the n’th echo intensity (at time t = n.2) can be calculated and reads (Appendix B); n 2 n 2 3 1 2 M n M 0 exp D 2G02 exp ( D 2G02 )t 3 3 T2 T2 (4a) Figure 8A shows the echo envelope of bulk water as derived from a CPMG pulse sequence (Figure 7) for different times . If no diffusive motion occurs (D = 0) the different echo-envelopes will be identical and independent of . However, as can be inferred from Figure 8A the slope (1/T'2) of the echo-envelope increases with increasing (Figure 8B) and is emphasized by the apparent spin-spin relaxation rate 1/T’2 being a function of 2 (Figure 8B). Figure 8A) The echo signal intensity of bulk water as obtained from a CPMG pulse train with different time distances (2) between successive -pulses (see Figure 7). The solid curves represent non-linear least squares fits to Eq.4a. B) The apparent spin-spin relaxation rate (1/T`2) versus . The true spin-spin relaxation rate (1/T2) was determined from the intercept ( = 0) of a second order polynomial fit in 2 (Eq. 4b), resulting in T2 = (3156 + 50) ms. 6 This behavior is indicative of a diffusive motion in an inhomogeneous magnetic field. If assuming the magnetic field experienced by the water molecules to be approximated by a constant gradient field G0, i.e., B = B0 + G0z, it is possible to show that the observed rate (1/T’2) of the decay of the echo-envelope can be expressed by the following formula (see appendix 2); 1 1 2 2 DG 02 ' T2 T2 3 (4b) where D represents the self-diffusion coefficient of bulk water. The dotted (red) curve in Figure 8B represents a non-linear least squares fit to a second order polynomial in 2 and explains semi-quantitatively the experimental data. The true T2 was derived from the intercept of this curve with = 0 (Figure 8B) and reads T2 = (3156 + 50) ms, showing that T1 ≈ T2, as expected for bulk water. Exercise 2; Measure T2 of water confined in glass beads and discuss the results with respect to T2 of bulk water. What is F2 = T2,pore-water/T2,bulk-water? Is F1 = F2 ? What can you say about the homogeneity of the magnetic field within the pores? Is it different from the homogeneity observed in bulk water? Diffusion In the previous section we noted that diffusion of molecules within an inhomogenios magnetic field might have a significant effect on the slope of the echo envelope when applying a CPMG pulse sequence. In this section we will see how to take advantage of this effect by designing a controlled inhomogeneity along the static magnetic field by generating gradient pulses for a certain time duration (pulsed gradient fields) along the zaxis. The simplest pulse sequence to consider in this case is illustrated in Figure 9. Figure 9. Illustration of the simplest pulsed field gradient scheme used to measure diffusivity. g represents the strength of the gradient field of duration . The timing of both rf-pulses and gradient pulses are illustrated along the time axis. 7 From basic NMR theory the following relation between magnetization (M), gradient field strength (g), diffusivity and the time distance between the /2-pulse and the -pulse can be derived, ; 2 M exp exp 2 2 g 2 ( / 3 )D M0 T2 (5) where is a constant denoted the gyromagnetic ratio (= 2.675.108 rads-1). When measuring the diffusivity of fluid molecules confined in porous materials the effect of internal gradients (Exercise 2), eddy currents (caused by strong gradient pulses), unwanted echoes (when applying more than a single rf-pulse) and the observation that T2 is frequently much shorter than T1 must be considered. This calls for designing a pulse sequence of a significant more complexity, denoted the “13-interval pulse sequence”, as illustrated in Figure 10. It is beyond the scope of this project to detail the derivation of a formula relating M, D and g. However, the approach is the same as for deriving Eqs 4a and 5 (Appendix B and C). We simply present the result (Eq 6) without further discussion; Figure 10. Illustration of the “13 interval pulse gradient stimulated echo sequence” using bipolar gradients with g representing the strength of the gradient field of duration . The timing of both rf-pulses and gradient pulses are illustrated along the time axis. 2 M exp exp exp 4 2 2 g 2 D(t )t M0 T2 T1 (6) t 3 / 2 / 6 Eq 6 shows that D of a confined fluid depends on the diffusion time t. In contrast, for bulk solutions D is independent of tD. Due to the spatially restricted diffusion of a pore confined fluid, an increasing fraction of the fluid molecules will sense this restriction with increasing diffusion time. Hence, we expect the effective diffusivity D to decrease with increasing diffusion time. For long diffusion times, the diffusivity will approach a limiting value, corresponding to the long-range diffusivity limit. 8 Using general physical arguments it can be shown that for short diffusion times the following Eq can be derived (P.P.Mitra, P.N.Sen, L.M.Schwartz, Phys. Rev. B, 1993, 47, 8565) D(t D ) 4 S S 1 S 1 D(t )t D(t )t t D(0) 6V R0 6V 9 V (7a) where 1/R0 represents the curvature of the restricting geometry and defines the surface relaxation strength. For shorter diffusion times, Eq 7a simplifies to; D(t ) 4 S 1 D(t )t D(0) 9 V (7b) Figure 11 (left) shows the signal intensity of bulk water for different diffusion times tD as a function of the gradient field strength squared (g2) using the 13-interval pulse sequence depicted in Figure 10. The dotted curves represent non linear least squares fit to Eq 6. The derived diffusivity as a function of diffusion time is plotted in Figure 11 (right) and confirms that (for a bulk solution) the diffusivity is independent of diffusion time and equals (2.58 +0.08).10-9 m2/s. Figure 11. Observed echo intensity (normalized) of bulk water as a function of diffusion time (tD) and gradient field strength squared (left) and the corresponding bulk water diffusivity as a function of diffusion time (right) . Exercise 3; Measure the diffusivity of water confined in glass beads and plot the diffusivity against diffusion time. Estimate the diffusivity for short and long diffusion times. Determine the surface-to-volume ratio (S/V) of the pores from the slope of the D(tD)-curve for short diffusion times (Eq 7b). 9 10 Appendix A. Spin-lattice relaxation time of fluid molecules undergoing fast exchange (on an NMR time scale) between two different regions in space. Assume fluid molecules to be confined in a pore of volume V and surface area A (Figure A1). The fluid molecules sensing the pore matrix surface is defined by a relaxation rate 1/T1s while the bulk fluid molecules within the pore have a relaxation rate identical to the bulk fluid, 1/T1b. Figure A1. Illustration of a random pore geometry with volume V and surface area S. The thickness of the fluid at the surface is d. If we assume that the molecules at the surface (dark region) exchange with molecules within the pore (light area) on a time scale which is fast compared with the NMR time scale, we expect that the observed relaxation rate of the fluid molecules to be expressed by (when assuming the density within the two regions to be the same). ; V 1 1 Vb 1 s T1 V T1b V T1s (A1) Since VS ≈ d.S and V = Vb + Vs we can write Eq A1 in the form; 1 1 d S 1 1 ( ) T1 T1b V T1s T1b (A2) If T1s << T1b (which is often the case when the interaction between the matrix and the surface molecules is significant), Eq A2 simplifies to; 1 1 d S 1 1 S T1 T1b V T1s T1b V (A3) The parameter (= d/T1s) defines the relaxivity parameter. 11 Appendix B. Spin-echo intensity observed in a constant magnetic field gradient. It can be shown that for fluids undergoing diffusion in a gradient field (g), the Bloch equation takes the form; M M izgM 2M t T2 with; M M x iM y (B1) After some complex and elaborate calculations (R.F. Karlicek and I.J. Lowe, J. Magn. Res., 1980, 37, 75 and R.M. Cotts, M.J.R. Hoch, T. Sun and J.T. Markert, J. Magn. Res., 1989, 83, 252) the solution to Eq B1 can be written; t t' 2 2 M M exp t1 / T2 D ( g (t ' ' )dt ' ' ) dt ' 0 0 0 (B2) where D is the diffusion coefficient, g(t’’) is the total magnetic field gradient, T2 is the spin-spin relaxation time and t1 represents the duration when the NMR signal is influenced by transverse relaxation processes. In practical use, M and M 0 can be replaced by I and I0. We will apply Eq B1 to the following situation; Figure B1A) A spin-echo pulse sequence performed in a static magnetic gradient field G0. B) Due to the -pulse, the effective gradient magnetic field is inverted. To apply Eq B1, we set up the following Table. Table B1. Effective gradients and integrals1) 12 Time interval nr. (i) Time interval Gradient g(t’’) 1 t1=0, t2= G0 t' t' ( g (t ' ' )dt ' ' ) 2 0 G 2 t' 2 0 G 2 ( 2 t' )2 0 g i (t ' ) g (t ' ' )dt ' ' 0 g ( t' ) G0t' 1 t t' ( g( t' ' )dt' ' )2 dt' 0 0 G02t 3 / 3 -G0 t2=, g ( t' ) G0 ( 2 t' ) 2 G02 (4 2t 2 t 2 t 3 / 3) t3=2 1) Note, since g(t’’) is constant, it follows that gi(t’) must be a linear function in t’, i.e., gi(t’) = g(t’’)t’+ i. Also, since we inquire gi to be continuous throughout the time region t’ we must have; gi(ti+1) = gi+1(ti+1) for all possible i, which makes it possible to determine each i. For simplicity and without loss of generality we can choose 1 = 0 2 We can now easily calculate the last exponential term in Eq B2 by insertion, i.e.; t t' 0 0 2 ( g (t ' ' )dt' ' ) dt' G02 t '3 / 3 0 (4 2t 2 t 2 t 3 / 3) 2 2G (B2) 2 3 /3 0 The first echo intensity will thus have the intensity; I (2 ) exp(2 / T2 2 DG02 2 3 / 3) I (0) (B3) Likewise, the second echo at t = 4 will be; I (4 ) exp(2 / T2 2 DG02 2 3 / 3) I (2 ) (B4) I (4 ) exp(2 / T2 2 DG02 2 3 / 3) exp(2 / T2 2 DG02 2 3 / 3) I (0) We can thus easily find the echo intensity at t = n.2 to read; I (n 2 ) I (t ) exp(2 / T2 2 DG02 2 3 / 3) I (0) I (0) n (B5) exp(n 2 / T2 2 DG02 2 n 3 / 3) exp t (1 / T2 DG02 2 2 / 3 Eq B5 is equivalent to Eq 4a in the main text. 13 Appendix C. Spin-echo intensity obtained by applying pulsed gradient fields. Let us calculate the echo intensity from the pulse sequens shown in Figure C1 Figure C1. Illustration of the simplest pulsed field gradient pulse sequence used to measure diffusivity. g represents the strength of the gradient field of duration . The timing of both rf-pulses and gradient pulses is shown along the time axis. We use the same approach as discussed in appendix B Table C1. Effective gradients and integrals1) Time interval nr. (i) Time interval Gradient g(t’’) 1 t1=0, t2= t2=, t3= 0 t3 t4=3/ t4 t5=3/ 0 g 3 ( t' ) g g 2 2 g 2 2 t -g g 4 (t ' ) gt g (3 ) / 2 g 2 (t '2 (3 )t ' g 2 (t 3 / 3 (3 )t 2 / 2 (3 ) 2 / 4) (3 ) 2 t / 8) 2 3 4 g t' g i (t ' ) g (t ' ' )dt ' ' 0 g 2 (t ' ) gt g ( ) / 2 t' ( g (t ' ' )dt ' ' ) 2 0 t' 2 ( g (t ' ' )dt ' ' ) dt ' 0 0 0 0 g 2 (t '2 ( )t ' g 2 (t 3 / 3 ( )t 2 / 2 ( ) / 4) 2 t ( ) 2 t / 8) 0 0 t5 0 g 5 ( t' ) 0 t6=2 1) Note, since g(t’’) is constant, it follows that gi(t’) must be a linear function in t’, i.e., gi(t’) = g(t’’)t’+ i. Also, since we inquire gi to be continuous throughout the time region t’ we must have; gi(ti+1) = gi+1(ti+1) for all possible i, which makes it possible to determine each i. For simplicity and without loss of generality we can choose 1 = 0 5 We can easily calculate the last exponential term in Eq B2 by insertion, i.e.; 14 t t' 0 0 2 ( g (t ' ' )dt ' ' ) dt ' (t 3 / 3 ( )t 2 / 2 ( ) 2 t / 8) ( ) / 2 ( 2 t ) ( ) / 2 g2 (3 ) / 2 3 2 2 (t / 3 (3 ) t (3 ) t / 8) (3 ) 2 (3 ) / 2 ( ) / 2 (C1) 2 g 2 ( / 3) D Hence, I exp 2 g 2 ( / 3) D I0 (C2) Eq C2 is equivalent to Eq 5 in the main text. 15 A Simplified User Manual for the Maran Ultra NMR Instrument (Non-expert User Manual) Before initiating new experiments do the following 1. Insert sample (10 mm height) in correct position 2. Set RD to approximately 5*T1 (5s) 3. Set P90 to 2.15 (s) and RG =1 4. Sequence → load → FID.EXE → Open Optimize Receiver Gain (RG), Offset (O1) and /2-Pulse Length (P90) 1. Commands → Auto O1 (wait) 2. Commands → Auto RG (wait) 3. Commands Auto P90 (wait) Acquiring an FID 1. Sequence → load → FID.EXE → Open 2. GO Store the FID 1. File → Save As → (file name) T1 Measurement 1. Acquisition → Sequence → Load → INVREC.EXE → Open 2. .T1 → -list (file name) → Open → OK→ File name..(for storing T1 data) → save 3. A plot will appear on the display at the end of the experiment”, press; OK. Calculating T1 1. Process → T1 → Enter file name (T1 data) → Yes → T1 (with uncertainty) is calculated and presented on the display. 2. Alternatively; WinFit → File → Open → Select file → data → Select Fit Option →Auto Initialize → Fit → Data (Read out values), or print, i.e.; File → Print 3. You may also read the T1 data within an excel spread sheet; Retrieve excel → File → Open → File name (*.INT) T2 measurement Acquisition → Sequence → Load → CPMG.EXE → Open Check that SI = 1 TAU (Set a -value in microseconds) NECH (number of echoes), which must be chosen according to the expected T2 and the TAU (NECH*TAU*2 ≈ 5*T2) 5. GO 6. File → Save As → (file name…..) 7. Store as *.xls file (File → Export → file name) Calculating T2 8. After acquisition, type; T2 (T2 based on a single exponential fit). 9. File → Save As → M:\........... (file name) 1. 2. 3. 4. 16 10. Alternative; WinFit → File → Open → Select file → data → Select Fit Option → Auto Initialize → Fit → Data (Read out values), or print, i.e.; File → Print Initiating diffusion measurements 1. Acquisition → Sequence → Load → CPMGB13.EXE → Open 2. Set: SI = 512, DW = 0.1, NS = 8, RD = 7000000, DEAD1 = 3, DEAD2 = 5, D1 = 100, D2 = 500, D3 = 300, D7 = 100, G1 = 100, G2 = -100, RG = 20, C1 = 4, C2 = 2, FW = 1E6, VT = 25 3. Commands → Auto RG 4. Commands → Auto O1 (wait) 5. Commands Auto P90 (wait) Diffusion measurement 1. . PFG_DIFF_AT_EWH 2. Files; G1 gradient list (f) G2 gradient lists (g), Experiment starts)1) 3. File → Save As → File name. 4. Change D7 (the tutor will give details about this) and repeat the measurement by starting from point 1 above. Calculating the self-diffusion coefficient 1. The tutor has prepared an Excel spreadsheet, which you will use for this purpose. Details will be given during the course. 17