Periodizing The American Century: Modernism

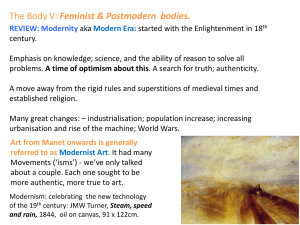

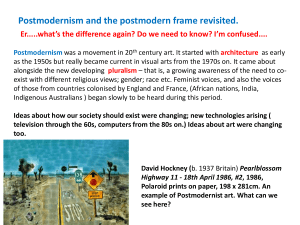

advertisement