WHY DO HORSES RUN RACES

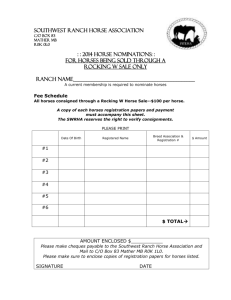

advertisement