Henri Nouwen on Story - Kingdom Story Ministries

advertisement

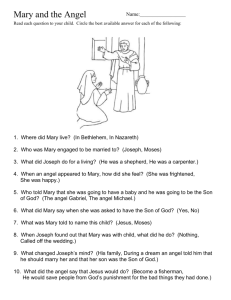

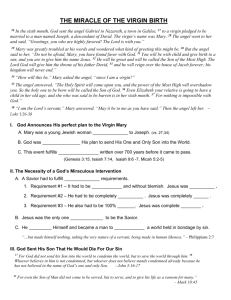

HENRI NOUWEN INTRODUCING US TO THE NATURE OF STORY “That is the beginning of a story-a time, a place, a set of characters, and the implied promise, which is common to all stories, that something is coming, something interesting or significant or exciting is about to happen. And I would like to start out by reminding my reader that in essence this is what Christianity is. If we whittle away long enough, it is a story that we come to at last. And if we take off his spectacles and push his books off to one side and say, “Once upon a time there was…,” and then everybody leans forward a little and starts to listen. Stories have enormous power for us, and I think that it is worth speculating why they have such power. Let me suggest two reasons. One is that they make us want to know what is coming next, and not just out of idle curiosity either because if it is a good story, we really want to know, almost fiercely so, and we will wade through a lot of pages or sit through a lot of endless commercials to find out. There was young woman named Mary, and an angel came to her from God, and what did he say? And what did she say? And then how did it all turn out in the end? But the curious thing is that if it is a good story, we want to know how it all turns out in the end even if we have heard it many times before and know the outcome perfectly well already. Yet why? What is there to find out if we already know? And that brings me to the second reason why I think stories have such power for us. They force us to consider the question, “Are stories true?” Not just, “Is this story true?”-was there really an angel? Did he really say, “Do not be afraid?”-but are any stories true? Is the claim that all stories make a true claim? Every storyteller, whether he is Shakespeare telling about Hamlet or Luke telling about Mary, looks out at the world much as you and I look out at it and sees things happening-people being born, growing up, working, loving, getting old, and finally dying-only then, by the very process of taking certain of these events and turning them into s story, giving them from and direction, does he make a sort of claim about events in general, about the nature of life itself. And the storyteller’s claim, I believe, is that life has meaning-that the things that happen to people happen not just by accident like leaves being blown off a tree by the wind but that there is order and purpose deep down behind them or inside them and that they are leading is that they are telling us that life adds up somehow, that life itself is like a story. And this grips us and fascinates us because of the feeling it gives us that if there is meaning in any life-in Hamlet’s, in Mary’s, in Christ’s-then there is meaning also in our lives. And if this is true. It is of enormous significance in itself, and it makes us listen to the story teller with great intensity because in this way all his stories are about us and because it is always possible that he may give us some clue as to what the meaning of our lives is. The story that Christianity tells, of course, claims to give more than just a clue, in fact to give no less than the very meaning of life itself and not just of some lives but of all our lives. And it goes a good deal further that that in claiming to give the meaning of God’s life among men, this extraordinary tale it tells of the lobe between God and man, love conquered and love conquering, of long-lost love and love that sometimes looks like hate. And so, although in one sense the story Christianity tells is one that can be so simply told that we can get the whole thing really on a very small Christmas card or into the two crossed pieces of wood that form its symbol, in another sense it so vast and complex that the whole Bible can only hint at it.” “How might the ministry of confrontation and inspiration express themselves in our daily ministry? I will limit myself to only one concrete suggestion: tell a story. Often colorful people of great faith will confront and inspire more readily than the pale doctrines of faith. The Book of Hebrews does not offer general ideas about how to move forward but calls to mind the great people in history: Abel, Enoch, Noah, Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, and many others. Then it says, “With so many witnesses in a great cloud on every side of us, we too, then, should throw off everything that hinders us, especially the sin that clings so easily, and keep running steadily in the race we have started.” (Hebrews 12:1). We guide by calling to mind mean and women in whom the great vision becomes visible, people with whom we can identify, yet people who have broken out of the constraints of their time and place and moved into unknown fields with great courage and confidence. The rabbis guide their people with stories; ministers usually guide with ideas and theories. We need to become storytellers again, and so multiply our ministry by calling around us the great witnesses who in different ways offer guidance to doubting hearts. One of the remarkable qualities of the story is that it creates space. We can dwell in a story, walk around, find our own place. The story confronts but does not oppress; the story inspires but does not manipulate. The story invites us to an encounter, a dialog, a mutual sharing. A story that guides is a story that opens a door and offers us space in which to search and boundaries to help us find what we seek, but it does not tell us what to do or how to do it. The story brings us into touch with the vision and so guides us. Weisel writes, “God made man because he loves stories.” As long as we have stories to tell to each other there is hope. As long as we can remind each other of the lives of men and women in whom the love of God becomes manifest, there is reason to move forward to new land in which new stories are hidden.”