Assistive Technology in K

advertisement

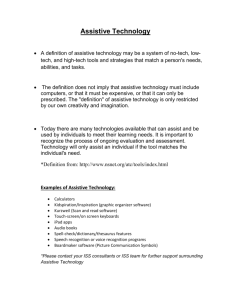

Assistive Technology in K-12 Schools: Understanding the Impact of the AT Consideration Mandate Dave L. Edyburn, Ph.D. September 29, 2004 A Roadmap to Provision of the Best Assistive Technology for Community Participation for People with Disabilities St. Louis, MO Given the federal mandate in IDEA that assistive technology must be considered when planning each student's IEP, it is reasonable to assume that K-12 schools offer fertile grounds to measuring assistive technology outcomes. However, there is little evidence to suggest that all students who could benefit from assistive technology have access to appropriate devices and services. The purpose of this presentation is to provide an overview of issues associated with the assistive technology consideration mandate and the implications for measuring assistive technology outcomes. Ten Issues Impacting Assistive Technology Use in Schools 10 Despite the consideration mandate, there is no evidence of systematic efforts devoted to ensuring that families are aware of their rights or the responsibilities of the school to assess the need for AT to enable a child to benefit from FAPE 9 AT Consideration models are nearly identical to the process of referral, qualification, and placement in special education which means they are subject to the same inherent limitations (i.e., time, cost, inefficiency, etc.); as a result, there is little evidence to suggest that all students who could benefit from AT have access to appropriate devices and services; those that do have AT tend to have an advocate that challenged the system 8 Policies and procedures focus on two components of a three-legged stool: AT devices and services with little regard for evidence that an intervention actually improves functional performance (hence, a third policy leg is needed: outcome) 7 Because funding issues have not been addressed, some criticize the AT consideration mandate as a blank check 6 Inadequate professional training in assistive technology means that IEP teams do not have the necessary knowledge and skills to effectively consider AT and that AT specialists are not commonly found in every school 5 An unintended consequence of the 1997 IDEA consideration mandate essentially added 4 million students to the AT case load by extending AT devices and services to high incidence disabilities 4 Considerable confusion surrounds the use of technology to enhance academic performance regardless of whether it is called assistive technology, instructional technology, or universal design 3 Historically AT has focused on extending physical and sensory functions; little attention has been devoted to assistive technology that functions as a cognitive prosthesis and the implications of these type of applications 2 Implicitly, learning is viewed as naked independence; when AT is used as a cognitive prosthesis (i.e., to compensate for an inability to read or store information that is difficult to remember) it is viewed as undermining standards and high expectations; confounding the educational system which wants to assign a letter grade (How do you grade a student who uses AT?) 1 While assistive technology has historically been viewed as a tool for facilitating access and participation, the current No Child Left Behind environment has fundamentally shifted the focus to research-based instructional interventions which not only close the achievement gap but demonstrate that all children are preforming at grade level Suggested Initiatives to Address Current Issues • Initiate a dialogue about the purpose of education and the role of technology tools in defining expectations for high-performance in 21st century citizens • Develop theories on technology-enhanced performance that serve to unify the constructs associated with AT, IT, and UD • Create new procedures to replace existing AT consideration models that identifies all students with a performance problem and provides appropriate tools and resources for enhancing performance (AT Child Find) • Develop a new generation of tools for facilitating decisions about technologyenhanced performance Selected References Denham, A., & Lahm, E.A. (2001). Using technology to construct alternative portfolios of students with moderate and severe disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 33(5), 10-17. Edyburn, D.L (2003). Rethinking assistive technology. Special Education Technology Practice, 5(4), 16-23. Edyburn, D.L. (2003). Measuring assistive technology outcomes: Key concepts. Journal of Special Education Technology, 18(1), 53-55. Also available online: http://jset.unlv.edu/18.1/asseds/edyburn.html Edyburn, D.L. (2003). Measuring assistive technology outcomes in writing. Journal of Special Education Technology, 18(2), 60-64. Also available online: http://jset.unlv.edu/18.2/asseds/edyburn.html Edyburn, D.L. (2003). Measuring assistive technology outcomes in mathematics. Journal of Special Education Technology, 18(4), 76-79. Also available online: http://jset.unlv.edu/18.4/asseds/edyburn.html Edyburn, D.L. (2004). Measuring Assistive Technology Outcomes in Reading. Journal of Special Education Technology, 19(1), 60-64. Also available online: http://jset.unlv.edu/19.1/asseds/edyburn.html Golden, D. (1998). Assistive technology in special education: Policy and practice. Reston, VA: The CASE/TAM Assistive Technology Policy and Practice Group. Smith, R.O. (2000). Measuring assistive technology outcomes in education. Diagnostique, 25(4), 273-290.