Collaborative Consumption and the Sharing Economy

advertisement

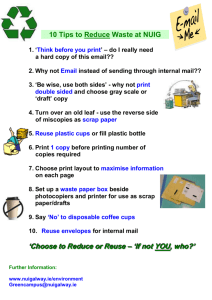

West Coast Forum Research Work Group Sustainable Consumption & the Sharing Economy Summary of Research Findings and Gap Analysis Topic: How state and local governments are promoting sustainable consumption and engagement in the sharing economy RESEARCH QUESTION(S) What is the state of knowledge about sustainable consumption? How is this defined or framed? What are the emerging trends? What potential roles can municipal and state governments play? What barriers have been identified and how might these be overcome? What strategies, techniques and policies are effective at promoting sustainable consumption through reusing, renting, repairing, and sharing products and materials? What GHG reduction benefits can be achieved through these activities? What strategies, techniques, policies and innovative approaches have not yet been tried but have been proposed that are considered to have greatest potential? Note: This research summary builds on the findings of a previous literature review “Changing Consumer Behavior” presented at the 2012 annual Forum meeting. Many of the issues and key findings related to sustainable consumption are addressed there. Sustainable consumption is a rich and nuanced topic for which extensive literature exists. While not the primary focus of this review, the concepts around sustainable consumption provide a context for exploring specific activities of individual consumers such as renting, repairing, reusing, borrowing, sharing of goods and the ways that governments engage in promoting, influencing and regulating these activities Background While the broader concept of sustainable consumption has been the focus of international policy and research, the formation of the “sharing economy” is an emerging trend that is just now capturing the interest of researchers, policy staff and elected officials. Consequently, much of the information available is found in the popular press including online sources, magazines and newspapers. There is a general lack of detailed information in peer-reviewed research 1 about the size and scope of the “sharing economy” and its contribution to local economic activity. There is also a lack of appropriate policies that address legal and financial barriers, and, generally, what state and local governments can do to promote it. Many of the terms and concepts are still evolving but a hierarchy is beginning to take shape. Historically, sustainable consumption has been defined as: “…the use of services and related products which respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life while minimizing the use of natural resources and toxic materials as well as the emissions of waste and pollutants over the life-cycle so as not to jeopardise needs of future generations.” (Oslo Symposium on Sustainable Consumption, 1994) At the consumer level, this refers to a broad range of consumption activities (reuse, renting, borrowing, sharing, repair) that support goals of improved material efficiency and reduced impacts. Some of the newer concepts of collaborative consumption and the sharing economy emphasize the aspect of social or informal exchange (as opposed to commercial) as a key dimension. Distinctions are still being refined and include peer-to-peer and business-tocustomer sharing, the importance of whether money is exchanged or if technology is fundamental to the model. For the purposes of this literature review, a broad search was conducted looking at all these terms along with specific activities such as renting, borrowing, sharing, repairing, and reusing to capture the greatest possible number of relevant sources and avoid conflicts in the various definitions still emerging. SUMMARY OF KEY FINDINGS General Much of the literature currently available focuses on the emergence of sustainable consumption activities and the underlying causes and cultural shifts that may be driving these trends. While the traditional repair industry has been in decline, new options such as iFixit and “repair cafés” have emerged along with other platforms supporting reuse, renting and sharing. This is due to advances in technology and the internet, the recent recession, changing attitudes about ownership, a growing sense of community and the green movement. Some estimates have been developed for the employment and revenue impacts associated with specific sectors or activities (e.g. rental, repair, reuse), including analyses from Minnesota and Eugene, OR, but no systematic analysis across a broader set of sectors and impacts was available. A few cities including Vancouver, BC , San Francisco, CA and Portland, OR have explored program and policy options to advance these activities and remove barriers. In addition, the State of California recently took action to remove regulatory constraints on ridesharing. One of the latest resources comes from the Sustainable Economies Law Center which released a September, 2013, report with recommendations for cities wishing to promote sharing activities and improved access to goods and services. While limited, potential government policies identified in the available literature include: 2 Removing legal and regulatory barriers to the development and operation of new business models such as Airbnb, Lyft and others. Providing grants and other assistance to stimulate the development of organized swaps, “repair cafés,” tool lending libraries, community gardens and other activities at the neighborhood level. Providing tradeshows, interactive maps and other information resource guides to connect providers and users of goods and services. Supporting car, ride and public bike sharing. Removing legal barriers to community-based food production. Facilitating construction of new unit additions to existing homes and very small homes. Lowering permitting barriers for home-based micro-enterprises. Emerging concepts and consumption patterns Sustainable consumption encompasses a broad range of consumption activities that reflect changes in purchasing and ownership patterns and the way consumers are meeting their needs for goods and services. Lorek and Fuchs draw an important distinction between “strong” and “weak” sustainable consumption. Strong sustainable consumption focuses on the question of “appropriate levels and patterns of consumption, paying attention to the social dimension of well-being, and assessing the need for changes based on a risk averse perspective.” Weak sustainable consumption, on the other hand, focuses on “improving the efficiency of consumption (primarily via technological improvements).” As such, weak sustainable consumption falls short in its ‘lack of attention t questions of justice, its inability to deal with the rebound effect and its neglect of overall limits.” Sustainable consumption is manifest at the consumer level in alternatives like renting, repairing, borrowing, sharing and reuse. Consumers engaged in these activities can meet their household needs in ways that reduce the impacts of their consumption and avoid the necessity (and costs) of acquisition and ownership. Instead of focusing on the end-of-life issues of recycling and disposal, the emphasis here is on reducing the upstream impacts associated with the production and consumption of goods and food, impacts such as greenhouse gas emissions, resource depletion and environmental toxicity. The term sharing economy has emerged as a way to describe the sharing of products, services, and information via information technology. Other terms include collaborative consumption, peer-to-peer sharing, and collaborative economy which may or may not depend on information technology for the sharing transaction. It’s important to note the distinction between sharing and short-term rental. Sharing is predicated on the notion that assets such as cars, tools and others but often sit idle creating “slack capacity.” Some platforms such as peerto-peer car sharing make these idle assets available for use, sometimes for a fee. Other businesses such as Zipcar provide short-term car rental from a fleet of vehicles owned and maintained by the business. The service to the consumer is similar, but the type of transaction and the related business model may be very different. The distinction becomes blurred when there is a fee for using the idle asset. 3 The report for the City of Vancouver “Promoting Innovation in Vancouver’s Sharing Economy” discusses the history of the term further and cites Lessig (2008) as distinguishing between the commercial economy and the sharing economy. The commercial economy is predicated on products and services having a tangible economic value, whereas the sharing economy goes outside the monetary system to focus on relationships for sharing (Ardis, Fernandez-Lozada, Schmidt and Tize, 2013). Sarah Lacy, author in PandoDaily, defined the peer-to-peer economy as informal side jobs and the sharing economy as formalized jobs that are the primary source of income (Lacy, 2013). This distinction points to the need for government oversight and regulation of the sharing economy. Most of the sources examined, however, use the term sharing economy as a hybrid of these ideas where something can be shared for free, exchanged or used for a fee. One of the newest and most widely used terms, collaborative consumption, was introduced by Botsman and Rogers in What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption (2010). They define the term more broadly as the sharing, bartering, lending, trading, renting, gifting and swapping through rapidly changing technologies. The four principles of collaborative consumption include: 1) Critical mass: Having enough momentum in a system to make it self-sustaining. 2) Idling capacity: The unused potential of items, such as drills or other infrequently used equipment. 3) Belief in the commons: By providing value to the community, we improve our own value. 4) Trust between strangers: Collaborative consumption takes out the middleman and requires trust among users. Relationship to materials management Changing consumer patterns that result in reduced material inputs are important for future production and consumption strategies. As reported in Materials Efficiency: A White Paper: The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that demand for materials will at least double by 2050 and that demand growth exceeds potential industry gains in efficiency. According to IEA, 56% of industrial CO2 emissions arise from production and processing of just five materials (steel, cement, plastic, paper and aluminum). The carbon emission reduction targets recommended by the IPCC cannot be achieved for the five key materials if future demand is met by the existing supply chain, regardless of how efficient it becomes. This suggests the need to derive more material “services” in the production and consumption processes beyond efficiency improvements and points to strategies such as longer product life, more intense use, repair and re-sale. Life extension is important for products with little impact in use but high impact in production. Early replacement may be best if the product is characterized by high use impacts and changing technology. 4 Consumers often choose to replace goods before the end of the useful life. The decision to delay product replacement depends on a shift of consumer attitudes; in some cases consumers may be motivated by an emotional connection and where disposal produces sense of loss. Some suggested solutions producers can employ include: Better information on durability Personalizing production Adding value during product life-cycle (extended warranties) Avoiding purchasing through leasing Use of products through a service provider Shared ownership Role of Cities In the paper, Sharing Cities (Agyeman, 2013), Agyeman reminds us that the nature of cities have always been about shared space. A city provides spaces in which people come together to share, and by definition, a city is a shared space. Within a city, the government has historically regulated the interface between the public and private sharing of things, services, and experiences. This interface is impacted by and plays a role in sustainable consumption and the sharing economy. With modern technologies, the intersection of urban space and cyber-space provides an unsurpassed platform for a more inclusive and environmentally efficient sharing economy. Inherent in this intersection is a dramatic cut in resource use. “City governments can increasingly step into the role of facilitators of the sharing economy by designing infrastructure, services, incentives, and regulations that factor in the social exchanges of this game changing movement.” (Orsi, Eskandari-Qajar, Weissman, Hall, Mann, and Luna, 2013) Recent trends Much of the available literature attempts to analyze the underlying drivers of changing consumption patterns. In a broad sense, historic consumption patterns are rooted in traditional consumerism. One article (Allwood, 2010) asserts that consumers have been driven to purchase goods for the following reasons: 1) Fashion rather than form or function. 2) Conveniences which leads to excess. 3) The rise of the throw-away society. 4) Marketing promotes anticipation of consumption which drives continued craving. In Spend Shift: How the Post-Crisis Values Revolution Is Changing the Way We Buy, Sell, and Live, the authors point to changing attitudes coming out of the recent recession (Gerzema and D’Antonio, 2011). Based on surveys of people and businesses about their values and spending habits, a new post-recession value set is evident that supports the community- based structure of the sharing economy. These values include: 1) Indestructible spirit (optimistic and resilient) - leveraging hardship into opportunity. 5 2) Retooling - self-reliant, retain faith in core traditions and seek better communities and selves. 3) Liquid life - adopting more nimble, adaptable and thrifty approach to life. 4) Cooperative consumerism - collaborate to solve problems and create new solutions. 5) From materialism to the material: old status symbols no longer hold appeal. Ownership patterns are changing, too, particularly among young adults. Some of the reasons suggested for this shift include: Consumers want a service rather than a product and are using their shared values to support alternative means for providing the services. Consumers often have a more environmental mindset to consume fewer of the earth's resources and they enjoy a sense of freedom to work or live anywhere without having to own a car or a house. Consumers now prefer “better” instead of “more” and believe that their choices can reconstruct capitalism to be creative instead of destructive. People are beginning to live with less yet feeling greater happiness and satisfaction. Nearly two thirds of survey respondents feel that they can affect corporate behavior through purchasing. The survey and study completed by Latitude and Shareable Magazine (Gaskins, 2010) focused on attitudes around use of technology in sharing activities. Some notable findings: 75% of respondents predicted their sharing of physical objects and spaces will increase in the next 5 years. 78% of participants felt their online interactions with people have made them more open to the idea of sharing with strangers, suggesting that the social media revolution has broken down trust barriers. Participants with lower incomes were more likely to engage in sharing behavior currently and to feel positively towards the idea of sharing than did participants with higher incomes. Regardless of income, more than 2/3 of all participants expressed that they’d be more interested to share their personal possessions if they could make money from it. Millennials were more likely to feel positively about the idea of sharing, more open to trying it, and more optimistic about its promise for the future. Participants aged 40+ were more likely to feel comfortable sharing with anyone at all who joins a sharing community (with varying levels of community protections in place) and to perceive “making new friends” as a benefit of sharing. The greatest areas of opportunity for new sharing businesses are those where a lot of services do not currently exist within a specific industry category and where a large number of people are currently either a) sharing casually (not through an organized community or service) or b) not sharing at all but would be interested to share. They include transportation, infrequent-use items, and physical spaces. The most popularly cited barrier to sharing was having concerns about theft or damage to personal property, but 88% of respondents claimed that they treat borrowed 6 possessions well. Reputation is increasingly becoming an important form of currency; communities that offer transparency (such as through open ratings and reviews) encourage good behavior and trust amongst members. Businesses can profit from collaborative consumption by adding sharing services to their business model (Melanson, 2011). Venture capitalists are backing “sharing” ventures at high rates and corporations are advised to start paying attention. Although competitive models may not bankrupt a large company, they could certainly eat away at business (Sacks, 2011). Trends in the reuse and repair sectors are mixed. Sectors showing growth include used merchandise stores, computer maintenance, motor vehicle parts and watch/clock/jewelry repair. However reuse and repair are declining for tire treading, furniture repair and upholstery, and the service/repair of televisions, radios, refrigerators, and other electronics (DEQ, 2007). The repair industry has been declining for several reasons: Most products are made in countries with low labor costs and then imported to developed countries with high labor costs. It is often cheaper and easier to replace a product than to repair it in a developed economy (McCollough, 2009). The increase in dollars spent on advertising in the last couple decades has encouraged consumers to replace products with newer, better looking, and sometimes technically superior products (McCollough, 2009). Products are designed for planned obsolescence (Botsman and Rogers 2010). This may be the case for some electronics that only last a couple years before the latest model comes out to replace it. Products are becoming less durable. Products made with lower quality parts overseas, such as in China, don’t last as long. On average, non-Chinese goods were rated to last more than twice as long as similar goods made in China. Legal and regulatory issues Trust is often identified as a barrier to the sharing economy (Economist, 2013) though there is some debate about this (Botsman and Rogers, 2010; Sacks, 2011). Several sources argue that business models for sharing have addressed this barrier through on-line user rating systems. Almost all on-line sharing sites require profiles for both parties and feature a rating system so that there is shared knowledge about the trustworthiness of members. This strategy establishes “reputation capital” for its members, encouraging them to preserve their reputations by doing the right thing and honoring the sharing arrangement. Author Crain Rance in Advertising Age (2010) takes a more satirical approach to reputation capital. He “warns” that soon there will be some form of network that aggregates people’s reputation capital across multiple platforms where you can google a person and get a complete picture of their trustworthiness just based on these platforms. Reputation capital may be a means to grow the sharing economy by addressing one of its greatest barriers - trust. The legality of some sharing models was another barrier frequently identified. Many of the new sharing platforms provide services similar to those currently regulated such as hotels (Airbnb) and taxis (ride-sharing platforms such as Lyft, Sidecar and Uber). Airbnb, the on-line 7 sharing platform for housing, is illegal in New York City and may be the subject of similar legal barriers in other parts of the country. New York City prohibits renting an apartment for fewer than 30 days as a way to prevent residential buildings from becoming illegal hotels. As recently as 2012, that prohibition was upheld in a court ruling against Airbnb. Attempts to restructure these provisions through state legislation in New York have so far failed. California, Oregon and Washington have “passed laws relating to car-sharing, placing liability squarely on the shoulders of the car-sharing service and its own insurers, just as if it owned the car during the rental period. The laws also prohibit insurers from cancelling owners’ policies.” (Economist, 2013) In California, a recent ruling of the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) legalized ride-sharing companies like Lyft, Sidecar and Uber. Companies will be regulated under a new category called "transportation network company" (TNC). According to CPUC, TNC services will be required to obtain a license from the CPUC, have a minimum of $1 million in insurance, vehicle inspections, driver training programs, a “zero tolerance” policy on drugs and alcohol, and criminal background checks. These policies will be reviewed in one year to evaluate the system. Benefits and opportunities A 2011 study from Minnesota, “Economic Activity of Minnesota's Reuse, Repair and Rental Sectors,” presents some useful findings on the economic value of these sectors. The authors estimate the economic activity and employment associated with used product sales, repairs and rental services for the state of Minnesota, employ 46,000 and generate at least $4 billion in gross annual sales. The study concludes that reuse activities retain and recirculate money in a local economy, offer consumers more choices and stretch the consumers' dollars. However the multiplier effect diminishes as the economy becomes larger because reuse spending displaces other spending within the same economy (Minnesota, 2011). A similar but more limited study for the City of Eugene, Oregon found that the reuse industry contributed over $16 million to the local economy. While no comprehensive economic analysis was available for the sharing economy, one estimate is that the market is worth $26 billion (Botsman and Rogers, 2010). It’s important to note the potential limits to sharing of household items. While infrequently used items with idle capacity are generally good candidates (e.g. power tools), other appliances and household equipment are not (washing machines, cooking appliances). Issues of convenience, practicality and access place limitations on the scale and scope of the sharing economy, especially for items owned by individual households. It will be useful to define the opportunities more specifically for purposes of both policy development and analysis. From a materials efficiency perspective, several business opportunities are associated with reuse and remanufacturing: 1) New revenue streams from second-hand supply chain. 2) Leasing of products. 3) Brand benefits of environmental leadership. 4) Vertical integration to capture value besides just more output. 8 5) Energy efficiency through reduced production. 6) Look at ratio of labor to energy/material costs from developing economies. 7) New supply chain partnerships such as design and demolition or design, repair and disposal/recycling. Another useful example comes from a case study on reuse in Japan (Matsumoto, 2009) that examines the growth and benefits of reuse by independent reuse business companies (IRBCs) and original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). The growth of IRBC's has provided competition to OEMs to engage in reuse and thus promote resource circulation in society. OEM’s may not have an incentive to offer reuse options because 1) new products have higher profit margin and 2) the sale of reused products decrease the sale of new products. The article suggests that policies are needed to promote reuse and establish competition within these markets. Government policies and strategies Historically, cities have supported sharing with public libraries as the most well-known example. More recently, cities have facilitated the development of tool-sharing libraries (Berkeley, CA launched its Tool Lending Library in 1979). Many cities are just starting to explore options for more actively promoting collaborative consumption and the sharing economy. Portland, Or, San Francisco, CA and Vancouver BC are among some of those experimenting with innovative strategies to foster sustainable consumption activities. Suggested actions from Policies for Shareable Cities (Orsi, Eskandari-Qajar, Weissman, Hall, Mann, and Luna, 2013) include: 1. Shareable Transportation a. Provide designated, discounted, or free parking for car sharing b. Incorporate car-sharing programs in new multi-unit developments c. Allow residential parking spot leasing for car sharing d. Apply more appropriate local taxes on car-sharing e. Create economic incentives for ridesharing f. Designate ridesharing pick-up spots and park-and-ride lots g. Create a local or regional guaranteed ride home program. h. Adopt a city-wide public bike-sharing program 2. Food and the Sharing Economy a. Allow urban agriculture and neighborhood produce sales b. Provide financial incentives to encourage urban agriculture on vacant lots c. Conduct land inventories d. Update the zoning code to make “food membership distribution points” a permitted activity throughout the city e. Allow parks and other public spaces to be used for food sharing f. Create food-gleaning centers and programs g. Recognize mobile food vending 3. Shareable Housing a. Support the development of cooperative housing b. Facilitate construction of accessory dwelling units 9 c. Encourage the development of small apartments and “tiny” homes. d. All short-term rentals in residential areas e. Factor sharing into the design review of new developments 4. Job creation and the sharing economy a. Expand allowable home occupations to include sharing economy enterprise b. Reduce permitting barriers to enterprises that create locally-controlled jobs and wealth c. Assist cooperatives through city economic development departments d. Make grants to incubate new cooperatives e. Provide financial and in-kind resources to cooperatives f. Procure goods and services from cooperatives g. Integrate cooperative education into public education programs The report for the City of Vancouver (Ardis, Fernandez-Lozada, Schmidt and Tize, 2013) also provides a comprehensive analysis of potential actions. 1. Recognize & Reward Sharing Economy Innovation: Campaign and rewards for best companies. 2. Dedicate Human Resources: Create a Sharing Economy Working Group modeled after San Francisco to identify local issues and opportunities 3. Spark New Connections: Help fund events like trade shows to help collaborative consumption groups meet each other and the public (Vancouver hosted one successful fair). Or make a web directory. 4. Power up Citizen Engagement with neighborhood associations (NAs): Organize NAs to promote sharing like in Portland. 5. Tune Development Bylaws to Support Sharing Activities: Could create incentives for car/bike sharing or co-housing. 6. Address Affordability of Supportive Spaces: Incentivize shared spaces in new developments and review stock of municipal buildings that could be rented or provided for free for sharing spaces. 7. Regulate Short-Term Accommodation Rentals: Revisit and evaluate regularly. One system could involve permits so short-term rentals register with the city so there is a formal process for fire code checks and complaints like B&Bs. Another option is a room tax either by renter or Airbnb. 8. Promote Safer, Smarter Cycling… And Bike Sharing: Exempt Vancouver from BC helmet laws 9. Maximize Existing Parking Spaces: Allow residents to rent out existing parking spaces that come with their property by having them register with city (to allow official way to lodge complaints). 10. Grow Urban Garden-Sharing: Change any zoning laws that inhibit gardening for trade/sale and offer easy to access permits (again, makes it official and a valuable way for Vancouver to collect information). Several regulatory tools are relevant at the state and federal government level. As mentioned previously, taxation, licensing, insurance requirements and other policies have been instituted 10 to enable sustainable consumption activities and new business models. Universal Product Codes (UPC) are another opportunity to increase reuse and repair among consumer and businesses (2009). The article, “A universal code for environmental management of products” offers a lifecycle UPC approach to provide for easier product identification both in recycling and reuse facilities. The codes can be linked to detailed product information which supports easier product repair and reuse. Finally, they can support consumers by providing recycling coupons and rebates. GAP ANALYSIS Opportunities abound for new research into sustainable consumption and the sharing economy and the role local government can play to support it. A much better understanding is needed of the scale and scope of relevant activities and the impact these may have on local economies. More refined and consistent definitions are needed along with analytical methods to assess the impact on jobs, taxes, access to goods and services, and other relevant measures. Cities need to explore how far sharing opportunities can be taken. Agyeman recommends that research or case studies need to be conducted to: Stimulate expansion and replication of sharing schemes Extend sharing into new (or less widely shared) resources, or Strengthen the underlying infrastructure and enablers of urban shareability. Research is also needed to address the relationship to economic development goals and activities. How does sustainable consumption align with local economic development which has traditionally focused on boosting retail and manufacturing? Are there market opportunities for local industries? How can local government facilitate a shift in production and consumption methods? More detailed and comprehensive studies are needed to address the question of regulatory barriers or conflicts. Analysis is needed of potential tools such as zoning, licensing, and taxation to enable new forms of shared ownership and access while addressing potential regulatory inequities with traditional industries. Finally, more insight into public opinion and effective marketing approaches would identify potential outreach strategies, pilot programs and other interventions. Bibliography Agyeman, J.; Duncan, M. and Schaefer-Borrego, A. “Shareable Cities.” Friends of the Earth. Sept. 2013. 11 “A study of the Economic Activity of Minnesota's Reuse, Repair and Rental Sectors.” Prepared By: Management Analysis & Development for Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. Nov. 2011. Ardis, L.; Fernandez-Lozada, S.; Schmidt, T. and A. Tize. “Promoting Innovation in Vancouver’s Sharing Economy.” A Report for the City of Vancouver. Jan. 17, 2013. Botsman, R., and R. Rogers. What's Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption. New York: Harper Business, 2010. Carr, A. "Airbnb: For Turning Spare Rooms into the World’s Hottest Hotel Chain." Fast Company (106-148). 2012. Web. 17 Apr. 2013. Economist, The. 2013. ‘All eyes on the sharing economy’ March 9 2013. Garcia, H. “Consumption 2.0.” Futurist, Vol. 47 Issue 1, (p6-8). Jan/Feb 2013. Gaskins, K. “The New Sharing Economy.” Latitude in collaboration with Shareable Magazine Downloaded from: http://latd.com/2010/06/01/shareable-latitude-42-the-new-sharingeconomy/. 2010. Geron, T. "California PUC Proposes Legalizing Ride-Sharing From Startups Lyft, SideCar, Uber." Forbes. Web. 30 July 2013. Gerzema, J., and M. D'Antonio. Spend Shift: How the Post-Crisis Values Revolution Is Changing the Way We Buy, Sell, and Live. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2011. Hartlaub, P. "Berkeley Tool Lending Library Inspires Others." SFGate. N.p., 17 Nov. 2010. Web. 02 Apr. 2013. Lacy, S. "Amid the Mania to Quantify the Sharing Economy, Do Sharers Want to Be Counted?" PandoDaily. N.p., n.d. Web. 2 Apr. 2013. Lewis, T, and E. Potter. Ethical Consumption: A Critical Introduction. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2011. Lorek, S and D. Fuchs. Strong sustainable consumption governance - precondition for a degrowth path? Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2011) pp 1-8 Lynott, J. "Portland's Sharing Economy: Borrowing, Swapping and Sharing." Neighborhood Notes. 30 Mar. 2012. Web. 16 Apr. 2013. Melanson, T. “Will you get your share?” Profit, Vol. 30 Issue 4, (p11-12). Oct. 2011. 12 McCollough, J. "Factors Impacting the Demand for Repair Services of Household Products: the Disappearing Repair Trades and the Throwaway Society." International Journal of Consumer Studies. 33.6 (619-626). 2009. McGrane, S. "An Effort to Bury a Throwaway Culture One Repair at a Time." New York Times. May 2012. Matsumoto, M. “Business Frameworks for Sustainable Society: A Case Study on Reuse Industries in Japan.” Journal of Cleaner Production. 1547-1555. 2009 Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. “Solid Waste Generation in Oregon: Composition and Causes of Change.” Waste Prevention Strategy Background Paper. Feb. 2007 Orsi, J, Y Eskandari-Qajar, E Weissman, M Hall, A Mann, and M Luna, 2013. Policies for Shareable Cities: A sharing economy policy primer for urban leaders. Shareable and the Sustainable Economies Law Center. Rance, C. “Collaborative consumption sounds great on paper, but watch out for your reputation and your privacy.” Advertising Age, Vol. 81 Issue 36, (p28-28). 11 Oct. 2010. Web. April 2013. Sacks, D. “The Sharing Economy.” Fast Company, Issue 155, (p88-131). May 2011. 13