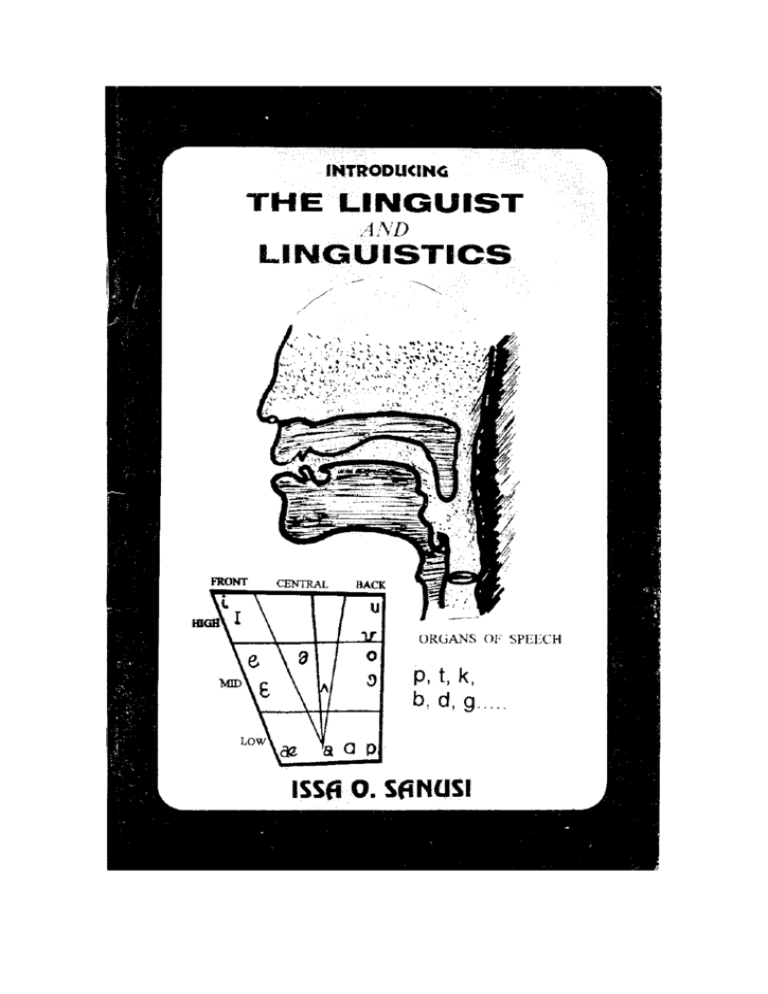

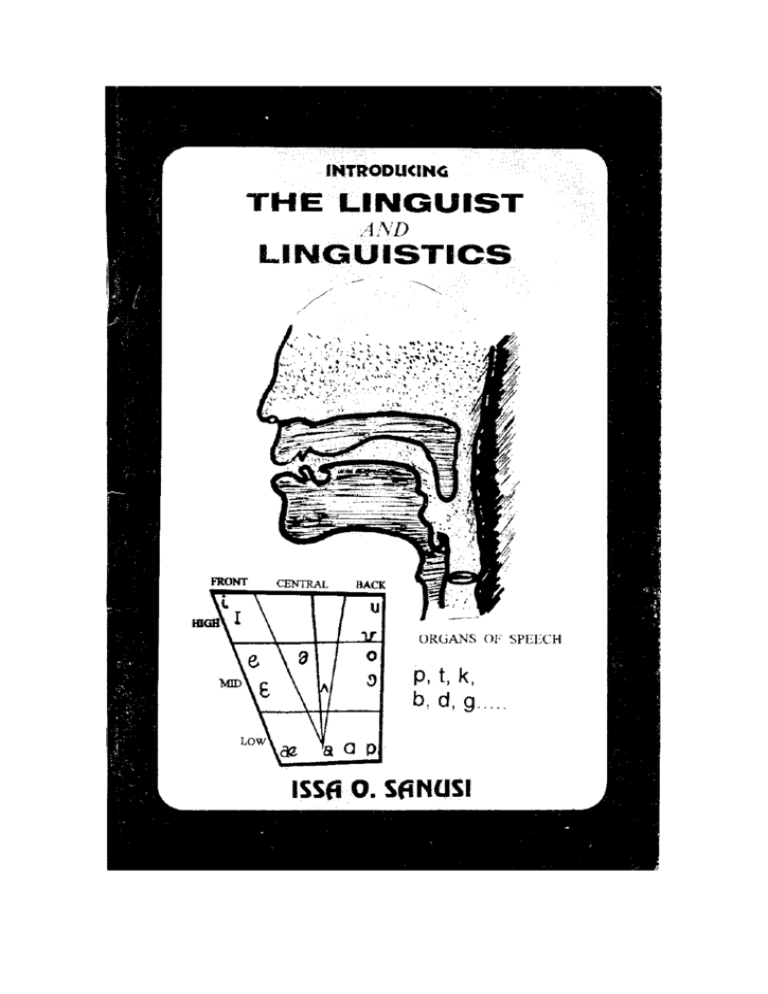

INTRODUCING

THE LINGUIST

AND

LINGUISTICS

ISSA O. SANUSI

2

Copyright© 1996IssaO Sanusi

ISBN 978- 102-0-6

First Published 1996

Published in Nigeria

by

JIMSONS PUBLISHERS

(Registered with Corporate Affairs Commission. Abuja No. 920514.)

20, Akure Road,

Adewole Estate,

P.O. Box 315,

Ilorin.

031-221153

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, adapted or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, recording, etc, without prior written permission of the

author.

Printed by:

Mudah Printing Press

G 99. Gambari Road.

Ilorin. Nigeria)

Cover Drawn by; Mr. A. A. Salami

3

DEDICATION

To my parents, teachers,

good friends, wife and children.

4

FOREWORD

Only a few individuals have ever heard of the discipline of Linguistic before,

and fewer still know what, exactly, it is all about. All too often, the assumption made

even by well educated laymen hearing the name for the first time is that any person

called an expert in it must be fluent in several languages, Mr. Sanusi’s aim in this

short, thoughtful book is to clear this and other popular misconceptions about

linguistics as an academic discipline. In six short chapters he discusses the nature,

aims, principles and major sub-divisions of the subject, and also highlights, for all

prospective students, some of the discipline's major areas of practical application in

Education, Government, Mass Communication and History.

The book fills an existing need, and all those who take enough trouble to read

through it are sure to gain some insights into this all important subject dealing with

human communication.

OLADELE AWOBULUYI

(Professor of Linguistics)

- Foundation Dean, Faculty of Arts,

- Foundation Head of Department,

Department of Linguistics and

Nigerian Languages,

University of Ilorin, llorin.

Nigeria.

3RD JULY, 1990

5

PREFACE

The urge to write this book was initially prompted by my experience as an

undergraduate student of linguistics My friends and room-mates in the University

often raised series of questions just to find out what exactly linguistics is, as a

discipline, and who actually could be referred to as a linguist. As a result of such

probing questions, I was always forced to define, from tune to time, what my course

of study-Linguistics' is all about.

I also faced similar task during my service year in Benue State. Any time I had

to introduce myself and my course of study to fellow corpers, they would always be

wanting to know what linguistics is all about. Their conception of linguistics was quite

erroneous and totally contrary to what linguistics actually is. For many of them, a

linguist is viewed as a polyglot.

The purpose of this book therefore is to define, m simple language and explain

in clear terms, what linguistics is all about and who could be correctly referred to as a

linguist. It is also hoped that the book will make explicit what exactly we have in

mind when we define linguistics as the scientific study of language.

Considering the narrow scope of this book, it is pertinent to state here that the

book is purely introductory, as regards the task of having to define and explain what

linguistics is all about and who a linguist is.

I hope this book will go some way towards removing some of the

misconceptions the general public has about linguistics and the linguist, and thereby

enlighten readers who are very new to the subject.

I have written this book with the sincere hope that readers from other

disciplines, as well as students of linguistics, having a first contact with linguistics,

will have an insight into, or probably a working knowledge of, some basic ideas about

linguistics as a course of study. It is also assumed that this book will be of some help

to Guidance Counsellors or Career Masters and Mistresses in introducing linguistics

to Secondary School Pupils, Students in Colleges of Education, Polytechnic and other

tertiary institutions; most especially in the aspects of career guidance. Such guidance

will be of assistance to those who may likely offer courses in linguistics or probably

6

specialize in linguistics as a course of study in higher institutions of learning. It will

also serve as a guide for students of Diploma programmes in language related fields,

My indebtedness to many earlier writers and experts in linguistics is

acknowledged on many pages of this book 1 am specially grateful to Professor

Oladele Awobuluyi. a distinguished and erudite scholar of linguistics, who read the

manuscript and made necessary corrections and offered invaluable suggestions

towards improving the original draft and for consenting to write a foreword to the

book.

Except for those ideas suggestions and styles that are personal, this book could

not have been written without the findings of all those authors listed in the

bibliography, as well as the stimulating ideas of my lectures during lectures and

seminars in the Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of

Ilorin, Ilorin,1 Nigeria (1980 - 1990)

The encouragement and assistance I received from members of my family,

good friends and colleagues served as impetus in writing this book.

I wish to acknowledge the contribution of Alhaji Umaru Saro towards the

successful completion of this book. May Almighty Allah continue to bless him and

lengthen his life.

1 sincerely thank Dr. Efurosibina Adegbija, of the Department of Modern

European Languages, University of Ilorin, whose critical comments and suggestions

have made this a better book than it would otherwise have been.

My sincere thanks also go to Dr. S A. Jimoh, the former Provost, College of

Education, .Oro, Kwara State, who is now in the Faculty of Education, University of

Ilorin, for his fatherly advice and moral support.

I am greatly indebted to all my lecturers in the Department of Linguistics and

Nigerian Languages, University of Ilorin, who over the years have taught me,

formally or informally, something about linguistics. They include Prof Oladele

Awobuluyi, Prof (Chief) Oludare Olajubu, Prof Beban S. Chumbow, Prof. Hounkpati

B. C. Capo, Dr. Yiwola Awoyale, Dr. Bisi Ogunsina, Dr. .Ore Yusuf, Dr. Francis

Oyebade, Dr Kayode Fanilola, Dr. Bade Ajayi, Dr Adewale Abolade, Dr Noel

Ihebuzor, Dr. L. Marchese, Dr. Victor Manfredi and many others.

7

Both the teaching and non-teaching staff as well as students in the department

have in one way or the other assisted the author in writing this book. I thank you all

Mr. Abdullahi Arije, who carefully typed the manuscript, also deserves special

mention.

Above all, all praise is due to Almighty Allah for giving me the thought and

wisdom to write the book.

Full responsibility for any errors or infelicities of style is , of course, solely my

own.

Issa O. Sanusi

August, 1983.

8

CONTENTS

PAGE

Foreword

.......................................... ……………………………………. ….

iv

Preface

...........................................................................................................

v

1.

Introduction ..........................................................................................

I

2.

Who is a Linguist? .................................................................................

3

3.

Why Study Linguistics? .......................................................................

8

- Functions of Language .....................................................................

9

What is Scientific in Language Study?...................................................

14

- A Brief History of the Theories of Grammar ....................................

17

-

Formal Grammar...............................................................................

18

-

Pedagogic Grammar ..........................................................................

22

Levels of Linguistics ...................... …………………………………...

29

-

Micro-Linguistics...............................................................................

29

-

Macro-Linguistics..............................................................................

37

Linguistics as a Career .............................................................................

48

- Entry Requirements .............................................................................

48

- Job Opportunities .................................................................................

48

Conclusion ............................................................................................

49

Notes.....................................................................................................

51

Bibliography ........................................................................................

53

Recommended Further Reading ............................................................

58

CHAPTER:

4.

5.

6.

9

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

In the layman's language, many people can simply and correctly define many

professions and courses of study in our schools and higher institutions of learning at

least to tell what actually such professions and courses of study are all about, and the

basic functions of the people who engage in them. Hence, most people think they have

a clear idea of what the more traditional subjects of the school or university

curriculum are about. This is why at social gatherings one does not often hear the

question - "What is Biology?'' or "What is Chemistry?" or "What is Mathematics?"

etc. But this is not the case with linguistics as a discipline. Anyone who introduces

himself or herself as a linguist to friends in any social gathering or perhaps in an

interview for employment, is quite likely to face such questions like "How many

languages can you speak?", "Can you speak my language?", "What is linguistics?" ,

"Who is a linguist?" , etc. All these questions point to the fact that people are not yet

acquainted with linguistics as a course of study.

At this point, one may ask the relevant question - 'Is linguistics a new course of

study?1 An answer to this question could be derived from the fact expressed by Alien

(1975:16), that:

Although linguists can trace the origins

of their subject back to the

fourth or

fifth century. B.C.., it is only

in comparatively recent

years

that

linguistics has begun to be studied and taught on a really wide scale.

In other words, compared to other subjects in our schools or university

curriculum, linguistics might be said to be a 'new' subject. This may not be

unconnected with why many people are yet to be aware of the existence of a subject

like linguistics as a discipline.

Many renowned erudite linguistic scholars (foreign and indigenous) have

written many works on the major aspects of linguistic analysis, i.e. syntax, phonology,

morphology, semantics, phonetics, historical linguistics, as well as applied linguistics;

however, such works are usually research works purely meant for the experts in the

10

field rather than for the laymen or beginners who want to know what linguistics is al]

about and who actually can be referred to as a linguist.

11

CHAPTER TWO

WHO IS A LINGUIST?

Many people (both literate and illiterate) in our society today believe that a

linguist is one who speaks many languages fluently without much difficulty. This is

no doubt a general misconception about linguistics and a linguist. Chumbow (1985:9)

refers to this kind of misconception as -'Innocent ignorance" about linguistics. To

correct this wrong notion, it is pertinent to state here that a linguist is not necessarily

someone who is a fluent speaker of many languages, either foreign or indigenous.

Going by the dictionary meaning of linguistics, the Oxford Advanced Learner's

Dictionary defines linguistics as "the study of languages or the science of language".

That is, the scientific study of language. Therefore, it would be more appropriate and

accurate to say that linguists are concerned with the scientific study of human

languages in general rather than being learners and fluent speakers of languages.

Attesting to this fact, Cook (1988:22) states that, "..... the linguist is not interested in a

knowledge of French or Arabic or of English but in the language faculty of the human

species".

However, it is an advantage if a linguist has a practical mastery of one or more

languages apart from his own mother tongue, but this is never an essential condition

for being a linguist.

The linguist studies the science of language as applicable to the understanding

of the structure of all and every human language. The job of the linguist, therefore,

includes:

(i)

studying the human language faculty,

(ii)

developing theories to explain language behaviour,

(iii)

providing the most efficient means for describing languages,

(iv)

making

the

most

accurate

and

comprehensive description of

languages available,

(v)

devising orthographies for the unwritten languages

(vi)

revising the orthographies of the written languages, as and when due,

12

(vii)

assisting

the

government

(vii)

writing phonetics manuals,

in

language

planning activities,

(viii) compiling dictionaries, etc.

By virtue of his training, the linguist has a flair for languages and is therefore

sensitized to features of every human language and to the complexity of such a

language, Revealing the competence of linguists. Sells (1985:7) remarks that,

"Linguists are in a sense language experts, for they, if anyone, have some idea of what

is English and what isn't'1.

Using linguistic theories, the linguist is able to understand both the simple and

complex structures of human languages and thereby make explicit the implicit

knowledge of a native speaker of a given language. That is, the application of

linguistic theories to languages makes it possible for the linguist to explain vividly the

intuitive knowledge, that is, the linguistic competence that a native speaker of any

particular human language possesses. The increasing awareness of the linguist about

languages makes him a language expert

As a result of his expertise or deep knowledge of how a language works, the

linguist knows the underlying reality of a language much better than the native

speakers of such a language.

The experience of the linguist is, therefore, acquired through his knowledge of the

theories of linguistics and the application of such theories to language data.

Bloch and Trager (1942:8) describe a linguist in the following revealing terms:

He is a scientist whose subject matter is language, and his task is to

analyse and classify the facts of speech, as he hears them uttered by

native speakers or as he finds them recorded in writing.

There

are

some

people

who

speak

a

good

many languages. The

ability to speak many languages does not make them linguists because they know

nothing about the underlying reality of language and how a language works. Such

people are better called 'polyglots1 or 'multilinguals' rather than linguists.

In a

nutshell, one who speaks many languages with every degree of fluency without a

knowledge of linguistics is merely a polyglot or multilingual and not a linguist.

Through the process of studying languages, a linguist may end up speaking a

13

number of languages; however, it is not necessary to be a speaker of many

languages in order to be a linguist.

One of the main tasks of training a linguist is to equip him with the theoretical

knowledge and technical know-how necessary to write a grammar of language (any

human language). In other words, a trained linguist can write the complete grammar

not only of the language he speaks but also a language he does not know. This is only

possible where the linguist has access to a native speaker of the language who will

serve as informant in providing relevant linguistic information on the language.

Thereafter, the linguist applies his acquired field work procedures and analytical skills

to tap the grammar out of the data collected from the native speaker. Every language,

no matter the number of people who speak it, has its own grammar and anyone who

speaks a language has internalized the grammar of that language. That is, he has the

implicit knowledge of the rules of grammar in that language. The primary duty of the

linguist is to discover the rules of the grammar and make explicit the implicit

knowledge of the grammar which the native speaker has mastered.

Unlike other school subjects, the teaching and learning of linguistics (as of

now) is still restricted to the four walls of some institutions in Nigeria. Perhaps, this is

why many people do not know that linguistics exists as a subject on its own. Be that as

it may, it is the opinion of this writer that as part of the effort to introduce linguistics

to the grassroots level some elements of general linguistics should be incorporated

into the secondary school curriculum as a subject in the Department of Languages.

This will enable linguists, or perhaps language teachers with some knowledge of

.linguistics, to use information from linguistics and (or) applied linguistics in teaching

languages and language skills to students (of Na Allah and Sanusi (1992) This will in

turn afford the students the opportunity of an adequate grasp of what is being taught.

In other words, a knowledge of linguistics and (or) applied linguistics is an advantage

in language teaching and learning. If this could be done, more and more people will,

in no distant future, get to know about linguistics as a discipline.

To make linguistics a familiar subject like every other school subject, experts

in linguistics must be ready to organize an4 participate in workshops, seminars and

symposia aimed at informing the general public (most especially language teachers)

14

about the role and place of linguistics in specific areas like: language teaching and

learning, language planning, language testing, development of orthographies for the

unwritten languages, writing of primers and readers in newly written languages, etc.

All these linguistic activities, requiring the services of linguists, are very necessary in

a multilingual country like Nigeria Hence the need for linguistic studies.

15

CHAPTER THREE

WHY STUDY LINGUISTICS?

Linguistics is worth giving proper attention simply because 'Language1, which

is its primary concern, is very useful in almost all facets of life and serves as the

primary medium of communication for mankind- It is a statement of fact that,

biologically, no other creature possesses a well -developed language faculty similar to

that of human beings.

Language is an essential part of man and his environment. It is, indeed, an

integral part of our socio-cultural heritage. Besides serving as a medium through

which we understand our historical past, language helps to bring diverse people closer

to one another and it is an instrument of unity among human beings.

Language is a medium of thought. It is a means of expressing our intentions

and emotions; reacting to human beings at different situations; influencing people at

different circumstances, etc Considering the relationship between language and

thought. Chomsky (1988:196) makes the following assertion:

The fact is that if you have not developed language, you simply don't

have access to most of human experience, and if you don't have access

to experience, then you're not going to be able to think properly.

Being a medium of thought, language is essentially required in the acquisition

of any form of knowledge either through educational or vocational training. Of course

speaking, writing, reading and listening comprehension can only take place with the

help of language as a medium of instruction. In other words, we use language to

impart knowledge and to acquire skills as well as to awaken and develop the

intellectual potentialities of a learner.

The effectiveness of educational or vocational training programmes depends

(among other things) on whether or not effective communication has taken place

between the teacher and the learners.

16

In a nutshell, acquisition of any form of knowledge and skills is made possible

through the use of a language, as a medium of communication. Therefore, what makes

language very crucial and useful is its creative nature, which determines man's

intellectual abilities. It is the creative nature of language that makes many of its

functions possible in any human society.

FUNCTIONS OF LANGUAGE

We use language in virtually everything we do and this makes it highly

indispensable in any society. Apart from using language in talking to fellow human

beings (in both formal and informal situations), we also use language in other aspects

of life like social interaction, administration, economic activities, mass mobilization,

law making, entertainment, etc. Without language, civilization would have remained

impossible.

It is through the medium of language that we are able to teach the younger

generations and ensure that civilizations progress from generation to generation.

Therefore, language could be seen as a phenomenon that makes all other things

possible.

It also facilitates the rate of inventions and discoveries in every human society.

Thus, it is the use of language that ensures socio-economic, political,

cultural,

religious, and educational developments all over the world.

From the foregoing, it is obvious that without language the world would be

very different from what it is today.

In other

words,

none

of the

above

mentioned language -dependent activities can be effectively carried out without the

use of language.

Language is a universal thread running through all cultures, knitting mankind into one

world community. It is chiefly through effective communication at home; school and

abroad that men will come to appreciate the inherent dignity of every human being

and will learn to live together in peace and harmony.

Every human language is endowed with prestige and such prestige is usually

commensurate with the prestige or influence of its speakers .However, linguists are of

17

the opinion that no language is superior to another. Rather, it is extralinguistic factors

like political power enjoyed by the speakers, the numerical strength of the speakers,

historical background, etc that determine the ultimate destiny of a particular language

Considering the power of language in any human society. Lowenfeld (1970) as

quoted in Chumbow (1985.1) observes that:

Language can be used to sooth anger, excite, tranquilize, stimulate,

intimate, energize,

stultify, create, destroy, assassinate or immortalize.

Word power is the one measurable element that has been found to be

present among men who have become leaders in any and all areas of

endeavour.

Language, as a medium of communication, is used in many human

interactional situations to express ideas, describe things or situations, convince,

deceive, criticize, commend, etc. It is, of course, a natural endowment that

distinguishes human beings from other creatures. Though many other living things

have different types of communication codes like hissing, screaming, cackling, and a

host of other par a linguistic codes, none could be likened to human language.

Language is generally human specific.

Not only the ability to produce words that distinguishes man from other

creatures; there are some other human communication codes that are quite distinct

from those of animals. For example, the way and manner a man laughs or weeps is

never the same as the way and manner

a cat mews,

a dog barks,

a horse neighs,

a goose cackles,

a monkey chatters, ;

a swine/pig grunts,

an ass brays,

an elephant trumpets,

an ox lows, etc.

18

The fact that language is inherently part of man makes many people take

language for granted. They do so simply because they grew up with their language

and found themselves speaking one language or another either consciously learnt or

otherwise absorbed without much effort.

A scientific study of language reveals that the nature, structure and functions of

human language are much more complex than we ordinarily take them to be at the

surface level. Linguistics is therefore seen as an attractive field of study for students of

language as a discipline, fort those who have a genuine flair for languages and for

those who possess a strong desire to recognize communication as a vital human

endeavour.

The study of linguistics at all its various levels, provides practical and effective

application of its -results to finding solutions to all .human problems. In other words,

the scientific study of language provides answers to scientific questions about the

nature, form, structure and functions of language, which in turn, provides for the

linguistic needs and services of man as well as national development. For example, by

practical application of linguistic theories and analyses, linguistic methods provide the

basic tools necessary for analyzing and describing many African languages which had

never been written before. For example, using his knowledge of descriptive grammar,

the linguist, in a developing country like Nigeria, assists in problems of language

teaching (foreign and indigenous), devising and revising orthographies, writing

primers, readers, or even textbooks in local or national languages.

In this connection, Bamgbose (1982) makes the assertion that the third world

linguists need not wait to be called upon to assist in such linguistic problems. The

linguists should be

prepared to think up ways and means of initiating many more projects like the Rivers

Readers project1, the Itsekiri Language project2, etc. with or without assistance of any

kind from the government.

Bearing in mind the relevance of linguistics to the educational domain, most

especially for pedagogical purposes, it is the opinion of this writer that some aspects

of applied linguistics (i.e. linguistics and language teaching) be incorporated into the

school curriculum, both at the secondary and tertiary levels. Such a move will, no

19

doubt, assist in teaching and teaming both foreign and indigenous languages without

much difficulty.

20

CHAPTER FOUR

WHAT IS SCIENTIFIC IN LANGUAGE STUDY?

Our frequent reference to linguistics as the scientific study of language might

prompt the question - what is scientific in language study? Linguistics as the science

of language seeks to know more about the phenomenon of language in all its

complexity. Linguistics is conceived as the science of language principally because it

approaches the study of language through scientific method and practice. Such

scientific methodology

and practice employed by linguistics in the study of

languages include:

(a) Data collection, transcription. observation, elicitation and analysis,

(b) Hypothesis formulation based on the observable facts from a language data,

(c) Empirical verification of the postulated hypothesis,

(d) Formulation of grammatical rules that are relevant to and derivable from

certain scientific theoretical framework in linguistics, etc.

The contribution of linguistics as a 'new' science is to increase one's

understanding of the nature, structure and functions of language. Therefore, it may be

said that the scientific study provided by linguistics is one which is based on the

systematic investigation of language data, conducted with reference to some general

theory of language structure. The linguist, in a scientific manner, studies language

data in order to discover the nature of the underlying language system, but he is not

likely to make sense of the data unless he has an understanding of the way in which

language is structured. Ideally, any theory of language structure that the linguist may

formulate must be checked against the data to make sure that the theory is consistent

with the observed facts of language use. Supporting this claim, Alien (1975:17)

remarks that,

In the working methods of all linguists, however, theory formulation and

the study of data have always proceeded side by side. We may say that

in linguistics, as in other areas of science, data and theory 'stand in a

dialectical complementation' and that neither can be profitably studied

without the other.

21

The aim is to present an analysis in such a way that every part of it can be

tested and verified, not only by the author himself, but by anyone else who chooses to

refer to it or make a description of his own based on the same principles.

The primary concern of a linguist when confronted with a new language is to

write the grammar of that language. The grammar in this sense is a set of rules

governing the usage of a language as a medium of communication. A linguist does

this by collecting and eliciting relevant data in the language. There are two possible

methods of data collection:

(a) Informant method

(b) Introspective method

In the informant method, relevant linguistic information on the language under

study is provided by an informant otherwise known as a 'language helper1, who speaks

the language as his or her first language or mother tongue.

On the other hand, the use of introspective method involves the linguist serving

as his or her own informant. This method describes a situation where the linguist is

directly working on his or her own native language.

Having collected and elicited relevant and ample data on the language, the

linguist formulates. rules, based on the observable information provided by his

analysis, to present general linguistic information derivable from the structure of the

language.

Pointing out the duty of a linguist, as regards grammatical analysis of a

language, Chomsky (1957:13) states that,

The fundamental aim in the linguistic analysis of a language (L) is to

separate the grammatical sequences which are the sentences of (L)

from the ungrammatical sequences which are not sentences of (L) and

to study the

structure of the grammatical sequences. The

grammar of (L) will just be a device which generates all of the

grammatical sentences of (L) and none of the ungrammatical ones.

In this manner, linguistics could be said to be an empirical science that

seeks to study language, as a medium of communication, from the purely scientific

perspective on the basis of observed language data. Such language data are always

22

subjected to critical analysis to determine the rules that govern effective and

meaningful communication in a given language.

In other words, a language is studied based on the grammatical rules operating

in that language. Many theories have been propounded for the purpose of grammatical

analysis.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE THEORIES OF GRAMMAR

Learning a language means learning the rules of the grammar of the language.

A grammar could be defined as an organized system or set of rules guiding the usage

of a language. This is exactly what we have in mind when we refer to the 'grammar' of

a particular human language.

According to Riemsdijk and Williams (1986:3) the term 'grammar' could be

defined in two senses:

In its most important sense, the grammar of a language is the knowledge that

we say a person has who "knows" the language - it is something in the head.

The study of grammar is the study of this specialized kind of knowledge how it is constituted, how it is used.

In its second sense, a grammar is a linguist's account of the "structure"

of a language, or a "definition" of a language.

Defining grammar in its technical sense, Radford (.1988:2) considers

grammar of a language vis-a-vis the different

levels of linguistic analysis.

According to him, grammar covers not only morphology (i.e. the internal

structure of words) and syntax (i.e. how words are combined together to form phrases

and sentences), but also phonology (i.e.

pronunciation)

and some aspects of

semantics (i.e. meaning) as well.

The fact that the process of sentence formation in any language is rule

governed is expressed in Stockwell (1977:1) as follows, "No language allows

sentences to be formed by stringing words together randomly. There are observable

regulations," Such observable regulations that are guiding the co-occurrence of

constituents in sentence formation are referred to as grammatical rules.

We can distinguish between formal grammar on the one hand and pedagogic

grammar on the other. While formal grammar presents a systematic account (or

23

description) of the linguistic knowledge or competence a native speaker of a language

possesses; a pedagogic grammar consists of materials extracted from one or more

formal grammars. Such materials are modified and adapted in such a way that they

could be used as the basis for language teaching. A pedagogic grammar, therefore,

could be viewed as a type of grammar designed to promote effective and efficient

teaching and learning of a particular language among the group of learners for which

the grammar is intended.

Many theories have been propounded for both formal and pedagogic

grammars. Such theories are used as theoretical framework or methodological tools

for analyzing language data.

FORMAL GRAMMAR

Some of the earlier formal theories of grammar that have been developed and

used as methodological tools for analyzing language data include the following:

(i) Traditional or Classical Grammar

(ii) Structural or Taxonomic Grammar

(iii) Systemic Grammar

(iv) Transformational Generative Grammar (T.G)

(v) Government and Binding (GB) Theory.

Other contemporary syntactic theories that are considered along with the GB

theory include Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG) (as in Bresuan (1982) and Falk

(1983) and Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar (G.RS.G.) (as in Gazdar, Klein,

Pullum and Sag (1985).)

In the history of syntactic models, traditional or classical grammar started as a

pedagogical grammar designed for teaching and learning some Indo-European

languages like Greek and Latin (cf Tomori (1977:3),

Proponents of traditional grammar include earlier philosophers like Aristotle,

Plato, Socrates, Trinysius Thrax, etc.

For the fact that traditional grammar lacks explicit and comprehensive general

theory, its practice involves making the analysis of the grammar of any language

reflect the grammar of Latin, This was regarded as one of the major weaknesses of the

grammar. However, despite the weaknesses of traditional grammar, many

24

grammarians consider it as the starting point, from which other theories of gra-mmar

emerged. In other words, many of the present-day theories of grammar could be

viewed as offshoots of traditional or classical grammar.

Structural or taxonomic grammar, popularly known as Bloomfieldian grammar,

was developed as a result of the inadequacies of traditional grammar. Structural

grammar came into limelight in the early 1950s. Proponents of the grammar include

Zelling Harris, Bernand Bloch, and Charles Hockett.

Structural grammarians offered the suggestion that each language should be

studied on its own merit without relating it to any other language; since every human

language has its own grammatical rules guiding sentence formation.

The development of transformational generative grammar (T.G.) through

Chomsky's Syntactic Structures early in (1957), which served as an improvement over

the existing structural approach to grammatical analysis, kept the ideas and

methodology of structuralism off the stage.

Using the structuralist ideas of his teacher (Zelling Harris), Chomsky

developed TG. as a model that attempts to explain the ability of a native speaker to

form and understand sentences in his native language.

Chomsky is of the opinion that the ability of the native speaker is the

'competence" and what the native speaker does when he uses utterance on specific

occasions is referred to as performance . Performance, then, is a reflection of the

native speaker's underlying competence (cf Chomsky (1965:4). It is this underlying

competence that transformational grammar seeks to explain That is, an attempt to

make explicit that knowledge which is implicit in the native speaker of a given

language

Another type of grammar, which has been employed in the grammatical

analysis of languages like English, is called systemic grammar. It is otherwise known

as 'Scale-and-category' grammar (of Haliday (1961:247-8). Tomori (1977:26- 64), etc.

For instance, using systemic analysis, five units are recognized in the grammar

of English: morpheme, word, group, clause and sentence. These five units of grammar

form a hierarchy or taxonomy.

25

In the systemic analysis, a sentence is ranked the highest consisting of one or

more clauses, a clause is said to compose of one or more words and so on, down to the

morpheme the lowest rank of abstraction in the hierarchy.

Government and Binding theory is the latest among the theories of grammar

mentioned in this book. It is Chomsky's current framework. The theory is named after

Chomsky's book - Lectures on Government and Binding, published in (1981). It is a

modular deductive theory of Universal Grammar (UG.) which posits multiple levels of

representation related by the transformational rule (move-alpha). The application of

move-alpha is constrained by the interaction of various principles which act as

conditions on possible representation. (See Awoyale (1995:116-7))

Associated with the principles are parameters which account for variation

across languages. Thus the grammar for a particular language is specified by the

appropriate parameter settings and a lexicon.

GB theory greatly eliminates proliferation of transformational rules like:

passive, affix hopping, verb -number agreement, question formation, equip-NP deletion, raising, permutation, insertion, etc.

Simply put, of all the numerous transformational rules we have under TG., only

the movement rules, alias move-alpha, are retained in the new GB theory; while others

are considered differently.

It should be noted that the kind of theoretical changes or development

discussed above is not peculiar to syntactic theories; similar development had taken

place at other levels of linguistics. ,, For example, in phonology, some of the

weaknesses or inadequacies of both generative phonology and prosodic analysis led to

the development of new phonologicaktheories like Auto-segmental phonology (ASP)

otherwise known as nonlinear or tiered phonology (as in Goldsmith (1976) and

Lexical Phonology/Morphology (as in Kiparsky(1982).

Apart from the above mentioned theories of formal grammar, we also have

some other theories that are devised for the purposes of language teaching and

learning. Such theories are considered as theories of pedagogic grammar.

26

PEDAGOGIC GRAMMAR

Many linguists and language teachers alike believe in the efficacy of linguistic

methods and techniques of analysis as well as the application of research findings in

linguistics in solving problems in language teaching and learning.

Some of the old and new theories of language teaching and learning, with

inputs from theoretical linguistics, include the following:

(i)

Grammar- Translation Method

(ii)

Direct Method

(iii)

Audio-Lingual Method

(iv)

Contrastive Analysis

(v)

Error Analysis, etc.

GRAMMAR - TRANSLATION METHOD

This is one of the oldest methods of language teaching In this method, both the

teacher and learners make use of the native language in learning the target language.

In other words, students are not allowed to make use of the language being studied.

They are only required to recite and learn by rote things like conjugations pf the

irregular verbs in the target language. The teacher spends most of his time translating

sentences, clauses, and phrases in the target language into the native language of the

learners.

It has been observed that under this method, a learner seldom speaks or hears

the language, but is expected to know the rules of its grammar. He spends a good deal

of his time translating sentences in the target language into the native language, with

the help of grammatical rules and a dictionary sometimes without understanding what

he translate.

It is therefore not surprising that students; taught In tin.-method often acquire a

mass of grammatical information about the language being studied, yet cannot speak a

word of it.

DIRECT METHOD

The direct method of language teaching was developed as a reaction to the

grammar-translation method. In this method, as the name implies, the teacher, from

27

the beginning, uses only the target language hi class, helping the students to

understand the foreign language with the help of gestures. He does not explain of

translate the grammar of the target language. The teacher aims at total immersion of

the students in the language. Although the lessons in this method are planned, they

generajly emphasize the new vocabulary rather than any other levels of linguistics.

Unlike the grammar-translation method, the direct method can teach a student

to speak and understand the target language; hut it can be extremely inflexible and

time-consuming.

AUDIO-LINGUAL METHOD

As a result of widespread reaction against grammar-translation method, the

audio-lingual approach assumed a position of favour in second language teaching.

It could also be said that the audio-lingual method was the outgrowth of a

swing away from the traditional methodology employed to teach Latin and Greek.

It is an approach to language teaching that considers listening and speaking (

the skills of oracy) as the first and central task in learning a language. While reading

and skills (the skills of literacy) are considered as secondary. Audio-lingual method is

popularly referred to as (aural - oral).

Some of the proponents of audio-lingua) method like Nelson Brooks believes

that language is primarily what is said and only secondarily what is written. In other

words, the audio-lingual stage, in language learning, which is a stage in which the ear

and tongue are trained, is considered to be the most important. It lays an indispensable

foundation for the other two skills (i.e. reading and writing;.

This method encourages that accurate pronunciation should be developed with

a good mastery of the sound system before the spelling system. This order is

considered to be the natural order.

This method has gained popularity in second language teaching, most specially

in the United States of America (U.S.A.) among experimental psychologists, cultural

anthropologists and linguists.

CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS

The publication in 1957 of Robert Lado's Linguistics Across Cultures marks

the real beginning of modem applied contrastive linguistics. Lado was of the opinion

28

that apart from eroding language teaching materials like text-bocks, there should be a

comparison between the source language or mother tongue (i.e. LI) of the learners and

the target language (i,e. L2)

Other proponents of Contrastive Analysis like Charles C. Fries. Di Pietro. etc. also

claimed that a systematic comparison of the source language and the target language at

all levels of structure, will generate predictions about the areas of learning difficulty in

the target language. On this note, it is assumed within the framework of Contrastive

Analysis that the best teaching materials will emphasize those features of the target

language that differ markedly from corresponding features of the source language.

Simply put, the theory stipulates that whenever the structure of a second or

foreign language differs from that of the mother tongue of the learners we can expect

both difficulty in learning and error in performance However, where the structures of

the two languages are similar, no difficulty is anticipated.

In summary, the aim of Contrastive Analysis is to compare both the source

language and the target language of a given group of learners with the hope of

identifying the areas of structural similarities and differences between ;lie two

languages. Having done this, the theory predicts the likely errors of the learners and

thereby provides the linguistic input to language teaching materials and curriculum

development.

Despite the relevance and applicability of Contrasts e Analysis approach to

second or foreign language teaching and learning, some reservations have been noted

in the application of the theory: Areas that were assumed to be difficult sometimes

turned out not to lead to errors and vice versa. Also, apart form interference from the

mother tongue, \\hich is the focus of Contrastive Analysis, errors in second language

learning may have physiological and psxcholoeical Origins. For example, lack of

attention, tiredness. forgetfulness. and a host of other lapses may lead to errors in both

spoken and written forms of the target language. This and many other weaknesses of

Contrastive Analysis led to the development of a new theory like Error Analysis.

29

ERROR ANALYSIS

As the name implies, unlike Contrastive Analysis, Error Analysis concentrates

on those erroneous parts of learner's performance in the target language that diverge

from whatever norn this performance is compared with.

The theory views the learner as one who interacts actively with the new

language, developing new hypotheses about the structure of the language he is

learning as well as modifying and discarding earlier formed ones. Proponents of Error

Analysis believe in studying the difficulties facing second language learners rather

than predicting such difficulties. Error Analysis therefore emerged as an alternative to

Contrastive Analysis approach.

In using Error Analysis as a methodological tool in second language teaching

and learning, one has to follow its tenets or procedures as a theoretical framework.

They include:

(i) recognition of errors,

(ii) description of errors,

(iii) correction of errors,

(iv) classification of errors, and

(v) explanation of errors,

According to Corder (1974 : 126). the most important stages in Error Analysis

are those of recognition, description and explanation of errors.

Some of the major works on Error Analysis include those of Nemser (1971),

Richards (1972), Selinker (1972), Adjeinian (1976), Corder (1977) and Brown

(1980).(see Sanusi(l988)).

30

CHAPTER FIVE

LEVELS OF LINGUISTICS

Like many other subjects, either in the school or university curriculum,

linguistics has various sub-divisions or levels. In each of such levels, 'language' is

normally focused as the subject matter. The levels constitute the different facets of

linguistic organization of any given human language.

Each level of linguistics has its own terminologies and techniques of analysis.

However, in order to ensure the natural pattern in which a language is structured, the

different levels must interrelate, pragmatically, in one way or the other, in the process

of using language as a medium of communication.

We can classify all the levels of linguistics under two broad headings:

(1) Micro-linguistics

(2) Macro-linguistics

MICRO-LINGUISTICS

The levels of linguistic analysis that are classified as micro-linguistics arc

those levels that arc

commonly referred to as descriptive or theoretical linguistics.

They form the central core of language

study. The major aspects of descriptive or

theoretical linguistics .include:

(i) Phonetics,

(iii) Syntax,

(ii) Phonology,

(iv) Semantics,

(v)

Morphology (vii) Historical Linguistics, etc

(vi)

Pragmatics

Some of these levels are briefly defined below, for the purpose of intimating to

our readers what each of the levels actually stands for..

PHONOLOGY

Phonology (also known as phonemics) is the study of the sound system (or

patterns) of language in terms of the functions of individual sounds in the words of a

language. In other words, phonology studies how sounds are modified in the -process

of word formation.

31

It is the level of linguistics that deals with how sounds are used in a particular

language in order to convey meaning.

Using phonological analysis, the linguist describes all the attested phonemes of

a language and their variants (allophones). He also determines whether two sounds

represent two different phonemes or they are variants of the same phoneme This is

done through the technique of "minimal pair". That is, comparing a pair of words that

differs in meaning as a result of difference in one sound segment. For example,

consider the following pairs of words in English:.

(a)

r a t

b

(b)

a t

p i n

(c)

p

a n

d

o g

d

o t

The words in each of the above three pairs are similar except for only one

sound. For instance, in (a) consonants hi and /b/ contrast in an identical environment

(i.e. word-initial position), in (b) vowels /i/ and /a/ contrast in an identical

environment (i.e. word-medial position), and in (c) consonants /g/ and / t / also

contrast in an identical environment (i.e. word-final position). Technically speaking,

these sounds that brought about the difference in meaning are said to be phonemic and

therefore constitute individual phonemes rather than being allophones or variants of

the same phoneme.

PHONETICS

Phonetics is the study, analysis, and classification of individual sounds of a

language. That is, it studies and describes the speech sounds of a language.

It should be noted that there is close interconnection between phonetics and

phonology — while phonetics is concerned with the study of individual sounds and

their pronunciation phonology focuses on the way in which these sounds are put

together, organized, and used in a particular language, in order to convey meaning.

There are three major aspects of general phonetics:

(i)

Articulatory Phonetics - the study of speech sounds in relation to the speech

32

organs that are used in pronouncing them. That is, the study of how sounds are

produced.

(ii)

Acoustic Phonetics — the study of the physical properties of speech sounds

and transmission of such sounds.

(iii) Auditory Phonetics — the study of the anatomy and physiology of the ear and

the process of perception of sound waves or impulses from the outer ear, middle ear

and inner ear.

The above three sub-divisions of general phonetics can be illustrated with a tree

diagram as shown in (Figure 1) below:

(Fig.l)

PHONETICS

`

Articulatory

Acoustic

Auditory

MORPHOLOGY

Morphology is the study of the organization of morphemes and words in the

process of word formation. It is that area of language study that • accounts for internal

structure of words.

A morpheme is the minimal meaningful unit of language. Morphemes are those

units that make up words. For example, the word 'child1 consists of only one

morpheme, while "childishness" consists of three: child, -ish, and -ness.

Morphologically, some words can be segmented or divided into their

morphological components, while some irregular words cannot be so divided. For

example, English words like: books, keeper, cooking, jumped, smaller, etc. can he

segmented into their morphological component parts: book-s. keep-er, cook-ing,

jump-ed, small-er, respectively. But some irregular English words like: men, mice,

feet, teeth, women, etc cannot be clearly divided into their various morphological

component parts.

All possible alternative representations of a particular morpheme are referred to

as allomorphs. As we have the concept of 'allophone' in phonology so do we have the

concept of 'allomorph' in morphology. In other words, the expression — 'Allophones

33

of the same phoneme* in phonology is similar to the expression — 'allomorphs of the

same morpheme' in morphology.

SYNTAX

Syntax is the study of the patterns of arrangement of words, or how words are

combined to form phrases, clauses, and sentences Syntactically, no human language

allows sentences to be formed by stringing words together randomly. Thai is. every

human language has regular and peculiar patterns in which words must combine to

form phrases, clauses, and sentences in that language.

The acceptable regular patterns of co-occurrence, among various constituents

of a sentence in any language, constitute what could be regarded as grammatical rules

in that language. Any attempt to violate such acceptable patterns, in forming

sentences, will always lead to ungrammaticality.

It is a matter of syntax that basic sentences in a language must follow a

particular basic word order. The basic word order shows how the subject, verb and

object co-occur hi any basic grammatical sentence.

The issue of basic word order is one of the universals of human language. Ft>r

example, languages like English, Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba exhibit Subject, Verb,

Object (i.e. S.V.O) word order in a given basic sentence. Languages like Japanese,

Batonu, Ijo (Kalahari), etc. display Subject, Object, Verb (i.e. S.O.V.) word order in a

given basic sentence, while languages like Arabic, Hebrew, Egyptian, etc. exhibit

Verb, Subject, Object (i.e. V.S.O.) word order in a given basic sentence.

SEMANTICS

Semantics is the study of meaning. For the fact that meaning'is the core of

communication, it has always been a central pan of the study of language and

communication systems. However, modern linguistics tends to doubt the possibii;ty of

studying meaning as objectively and rigorously as other levels of linguistics like

phonology and grammar. In their attempt to be scientific and objective, modern

linguists are compelled to reject anything that could not be objectively verified.,Thus,

some linguists like Leonard Bloomfield thought it would be desirable to limit the

scope of linguistics to observable data. This is why semantics, unlike other levels of

linguistics, has not received much attention.

34

PRAGMATICS

Pragmatics is the level of linguistics that deals with language use. It studies

how words are used and what exactly speakers have in mind in using certain word(s)

in a particular context. That is, how utterances ha\e meanings in situations.

A pragmatic study helps to differentiate between sentence-meaning and

speaker-meaning. While other levels of linguistics like phonology, syntax,

morphology and semantics concentrate on the rules guiding the possible combination

of different constituents of a language, pragmatics focuses on speakers"

'communicative competence'. That is, the knowledge required to produce and

understand grammatical utterances in relation to specific contexts and specific

communicative purposes.

‘Speech Act Theory’- is an aspect of pragmatics that is concerned with the

linguistic ACTS made while speaking, which have some social or interpersonal

purpose and pragmatic effect.

Three types of acts are differentiated under the speech act theory:

(i)

Locutionary Act (the act of uttering),

(ii)

Illocutionary Att (the act performed in saying something, e.g. Promising,

Swearing, Warning, e.t.c.).

(iii)

Perlocutionary Act {the act performed as a result of saying something, e.g.

persuading).

HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS

The field of historical-comparative linguistics traces relationships among

human languages as they change and diverge from a common original source (i.e.

parent language or proro-Ianguage). Historical linguistics is otherwise kno\\n as

diachronic linguistics,

Just as archaelogical discoveries provide information about prehistory, so also

do studies in historical-comparative linguistics provide information about historical

linguistic interrelations among different speech communities. Using the available

documents and linguistic evidence, historical linguistics describes the earlier forms of

a language. For instance, studies in linguistic history started to receive-greater

attention when linguists discovered that the resemblances in form between Sanskrit (a

35

language spoken in North India) and those of Latin and Greek (languages spoken in

Western Europe) were too close to be attributable to chance. It was the discovery of

similarities between the features of Sanskrit and those of Latin and Greek that led to

the conclusion, by linguists, that the three languages belong to or developed from the

same proto - form or mother language (i.e. INDO -EUROPEAN language).

Through the methodology provided by historical linguistics (i.e. Genetic

comparison and reconstruction), the linguist can reconstruct many features of an

extinct and unattested parent language from which the existing languages could be

presumed to be derived.

MACRO - LINGUISTICS

Those levels of linguistics that are popularly referred to as applied linguistics

are classified, in this book, under a broad heading - 'Macro - linguistics', in contrast to

other levels of linguistics earlier referred to as 'micro - linguistics'.

The development of applied linguistics represents an effort to find practical

applications for 'modern scientific linguistics'. In other words, applied linguistics

could be defined as the application of linguistic theories to other areas of study, for the

purpose of serving language related problems.

The term applied linguistics has two senses. In one sense, the term refers to any

area of inquiry where linguistic methodology, techniques of analysis, findings from

descriptive or theoretical linguistics may be applied to provide solutions to human

problems.

In this case, linguistics could be regarded as a means to an end rather than an

end in itself.

The term, in its second sense, is used in a more specialized sense to refer to the

application of linguistics to LANGUAGE TEACHING, most especially, the teaching of

a second or foreign language (i.e. a language that is not the mother tongue or native

language of the learners).

As rightly expressed by Crystal (1971: 258), each of the fields of applied

linguistics selects its basic information and theoretical framework from the overall

perspective which linguistics provides, and applies it to the clarification of some

general area of human experience.

36

Some of the major aspects of applied linguistics, in which research findings

from modem scientific linguistics have been applied, include the following:

(i) Sociolinguistics,

(ii) Psycholinguistics,

(iii) Linguistics and Language Teaching,

(iv) Lexicography,

(v) Language Planning, etc

Effort is made in this book to briefly define each of the above listed levels of

macro - linguistics as follows:

SOCIOLINGUISTICS

Sociolinguistics is the study of the structure and use of language in its social

and cultural contexts.

It is the study of language in relation to society Stubbs (1976: 19) describes

sociolinguistics as studies of how language is used in different social contexts such as

homes, factories, schools and classrooms.

Simply put, sociolinguistics involves the study of the ways in which language

interacts with society It looks at the social relevance of language as it relates to human

beings in their interpersonal and intergroup interactions. In other words, the concern

of sociolinguistics is the way in which the structure of a language changes in response

to its social functions in different social contexts.

However, it is the belief of some sociolinguists like J.B. Pride that the label 'sociolinguistics' should not be interpreted literally to mean a combination of

sociology and linguistics. That is, it is not appropriate for one to explain

sociolinguistics by merely enumerating the various disciplines which go into its

making. One has to indicate or show how such disciplines relate to each other in the

study of language.

PSYCHOLINGUISTICS

Psycholinguistics studies the interrelationship between psychology and

linguistics and defines the extent to which language mediates or structures thinking. It

describes how language interrelates with memory, perception, intelligence and many

other psychological factors.

37

In a nutshell, psycholinguistics deals with the psychological context of

language. Psycholinguists .are concerned with the task of constructing models that

account for mental processes.

Some of the major sub - divisions or sub - fields of psycholinguistics include,

(i)

Experimental or Developmental Psycholinguistics.

(ii)

Language Pathology.

Experimental or Developmental Psycholinguistics.

This is an aspect of psycholinguistics that deals with the regularities within the

components of language structure and use of language.

That is, a psychological

analysis of normal language development.

Language Pathology

Pathological Psycholinguisties is the asp«ct of psycholinguistics that examines

irregularities within the components of language structure (i.e. Aphasia or language

disorder). Communication may break down as a result of language pathology or

disorder.

Aphasia or language disorder occurs when the part of the brain that is used in

processing language is

damaged.

This may occur as a result of head injuries

sustained during accidents, falls or in certain violent acts Such brain

lead to either production or

communication

damage can

disorder The word -APHASIA is a

medical terminology that is used in describing different types of language

disorder.

That is, inability to produce grammatical and semantic structure. One who suffers

from any form of aphasia is called - aphasic.

TYPES OF APHASIA

There are various types of language disorder. Among the major types are:

(i) Amnesic Aphasia,

(ii) Dementia (Schizophrenia) Aphasia

(iii)Alexia or Dyslexia Aphasia, etc.

Amnesic Aphasia

This involves loss of memory or any form of memory problem. A patient

suffering from amnesic aphasia will find it very difficult to retain any information.

Apart from loss of retentive memory, such a patient will also have distortion in his/her

38

production of utterances. That is, he/she will not he able to process utterances in a

logical sequence.

Dementia Aphasia

People with dementia aphasia do not only have problem with retentive memory

but a total loss of proper speech production. This results in abnormal* verbal

behaviour that may lead to total break down in communication. Since there is lack of

control in speech, utterances produced by such a patient usually consist of

irrelevances.

Alexia/Dyslexia

There are two types of alexia or dyslexia:

(a) Phonological Alexia

(b) Verbal or Surface Alexia

Phonological Alexia / Dyslexia

This is a communication problem resulting from inability of the patient to read

individual letters that make up a word. That is, at the phonological level, people with

this type of language disorder find it very difficult to realize individual phonemes in a

word.

Verbal or Surface Alexia / Dyslexia

People with this kind of language disorder have problems in recognising

individual words as wholes, but they can identify individual letters that make up a

particular word. They often confuse words with similar structure.

THERAPY

For any of the above types of "Aphasia', therapeutic measures must combine

both anatomical and neurolinguistic techniques.

The anatomical approach consists of re-educating the patient and reconditioning of the speech organs affected.

Neurolinguistic approach uses both phonetic and phonemic techniques in

correcting the patient in the area of difficulty.

Generally speaking, investigation of first language or mother tongue

acquisition by children forms an important area of study in psycholinguistics

39

LINGUISTICS AND LANGUAGE TEACHING

Language teaching is another aspect of human endeavour in which insights

from linguistics can be profitably applied. Apart from knowing how to teach a foreign

language, the language teacher is expected to know how to analyse such a language. It

is in the aspect of analysis that the usefulness of linguistics becomes practically

obvious. In other words, ability to analyse a given language requires knowledge of

some background courses in linguistics.

A knowledge of linguistics enables the linguist to prepare language teaching

materials such as grammars, orthographies, dictionaries, primers, supplementary

readers, textbooks, etc. which are of immense benefit to both the language teacher and

learners.

A knowledge of linguistics helps the language teacher to understand, evaluate

and describe the language he is teaching. Some of the theories of applied linguistics

that are normally employed in language teaching are those theories described in this

book as theories of pedagogic grammar (see pages 22-28 ‘above).

LEXICOGRAPHY

Lexicography is another aspect of applied linguistics. It is the art and science of

compiling dictionaries. The process of compiling a dictionary, for a particular

language, involves identification, description, classification and definition of the

words of that language. All these activities require a good basic linguistic analysis.

One who compiles a dictionary is called - a 'lexicographer'.

A dictionary could be either monolingual ( i.e. written in one language) or

bilingual (i.e. written in two languages). The purpose of writing a dictionary for any

language is to provide useful information on the vocabulary of that language. A

dictionary is generally regarded as a reference book that provides readers with

different types of information on a particular language for which the dictionary is

compiled.

There are different types of dictionaries. They vary in size, volume, and price,

depending on the category of users for which each type is intended (see Sanusi (1994 :

116 -125)).

40

Among the popular types of dictionaries are: the pocket dictionaries, desk

dictionaries and the unabridged version. The unabridged version, as the name

suggests, is usually very hefty and voluminous.

LANGUAGE PLANNING

Language Planning is

generally

regarded

as

a

sub-discipline of

sociolinguistics (Kennedy (1982: 264)).

Das Gupta and Ferguson (1977) define language planning as -a process of

assessing language resources, assigning preferences and functions to one or more

languages and developing their use according to previously determined objectives.

Similarly, Weinstein (1980. 56), in his definition of language planning, states

that:

Language planning is a government-authorised, long-term,

sustained and conscious effort to alter a language's

function in a society for the purpose of solving

communication problems.

In language planning, the determination of language policy is a political

activity. Therefore, language policy decisions are made by politicians or the

government in power and not by professional linguists. Ideally, the task of language

planning is supposed to be delegated to expert planners and professional linguists.

Ironically, this' is often not the case. For instance, reporting a case of total neglect of

professional linguists in language planning activities in Nigeria, Awobuluyi (1979 : 3

- 4) wonders how well any official bodies would be able to advise the government on

so many highly technical issues relating to language in education and nation building,

without direct involvement of professional linguists.

Simply put, it would be erroneous for any government to embark on a serious

and meaningful language planning programme without a conscious effort to employ

the services of professional linguists.

Apart from those mentioned in this book, there are many other levels of

linguistics that may be classified either as micro-linguistics or macro-linguistics. The

major levels of linguistics discussed above can be diagrammatically represented as

given in (figure 2) below.

41

42

As clearly shown in (figure 2) above, linguistics has many areas of study which

have vastly expanded. However, despite the ever - increasing interest in different

aspects of linguistics as a discipline, it is almost impossible for -a linguist to be expert

in every aspect of the discipline. For example, an applied linguist who specializes in

language teaching and learning or socio-linguistics may not necessarily be an expert in

historical linguistics ( the study of the developments in languages across time) nor

does he necessarily know much about psycholinguisties ( the psychological aspects of

language).

Although, the more a linguist knows about all the related aspects of the subject

the better off he is as a linguist. He does not need to be an expert in every aspect of

linguistics. He can only specialize in one or two levels he has chosen as his area(s) of

interest. However, there are some talented individuals who are well - versed in general

linguistics.

43

CHAPTER SIX

LINGUISTICS AS A CAREER

ENTRY REQUIREMENTS

To study linguistics as a course in any of the Nigerian Universities, a candidate

must possess at least five ordinary level credit passes including a good credit pass in

English language, plus a credit pass in one of the three major Nigerian languages (i.e.

Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba), A knowledge of a foreign language like Arabic or French as

well as a flair for languages in general will be an added advantage.

Upon graduation from the University, qualified linguists have the opportunity

of being gainfully employed in many sectors of the economy.

JOB OPPORTUNITIES

Achievement in learning linguistics as a career is many -sided while some

qualified linguists may wish to remain within the teaching profession, others may

search for other prestigious jobs. A qualified and competent linguist can work in any

of the media houses, like the radio, television, newspapers, ere. He/she can also serve

in any of the advertising agencies, either as a secretary or public relations officer

(P.R.O.)

As an expert in language-related issues, the linguist has the opportunity of

being employed as a lexicographer - one who compiles dictionaries, or as a translator

or interpreter.

A professional linguist may be appointed by the government to serve on a

language planning committee ( i.e. a committe charged with the responsibility of

choosing and developing language(s) that will serve as national or official language(s)

in a given country.

The services of a professional linguist are also required in other allied

government projects like the Language Development Centre in Abuja, -the National

Institute for Nigerian Languages, Aba (Abia State), e.t.c.

Apart from being a language teacher, the linguist is in a better position to

prepare language materials for teaching either first or second language. Such materials

44

include orthographies, phonetics manuals, primers, supplementary readers, text-books,

e.t.c.

Since the use of language is involved in almost all human activities, qualified

and competent linguists have the opportunity of being gainfully employed in both the

public and private sectors of the economy.

CONCLUSION

Many people, who do not know, want to know what linguistics is ail about and

who the linguist is. Our aim in this short book is to define linguistics as a course of

study and introduce the linguist as an expert in language-related issues, rather than

being a fluent speaker of many languages.

Effort has been made in this book to highlight the major functions of human

language as a medium of communication The importance of linguistics in the

development of languages and its usefulness in various aspects of human endeavour

have also been stressed- On this note, linguistics is considered as a means to an end.

We are also of the opinion that, considering the relevance of linguistics to

language teaching and learning, language teachers should possess a basic knowledge

of linguistics and (or) applied linguistics in order to have a proper understanding of

both the nature and structure of human languages. This will afford such language

teachers the opportunity of adequate grasp of the grammar of any human language.

• A brief summary of the theories of grammar (formal and pedagogic), that are

used in analysing human languages, is presented in this book. The book has also

examined and classified some of the major levels of linguistics under two main

headings: micro - and macro-linguistics.

Finally, in this concluding chapter, we have tried to present linguistics as a

career- and discuss some job opportunities available to any qualified professional

linguist.

45

NOTES

1

The Rivers Readers Project is a project funded by the Rivers State government

in conjunction with some external agency or agencies. Directed by Professor Kay

Williamson, the project aims at producing primers and other teaching materials that

will make children in the Rivers state of Nigeria literate in their own language before

they proceed to seek literacy in English.

2

Like the Rivers Readers Project, the Itsekiri language project aims at ensuring

initial literacy in the mother tongue for the Itsekiri pupils and effective functional

literacy for the adults. The project is directed by Professor Ayo Bamgbose, a

renowned professional linguist and Nigerian National Merit Award Winner. Unlike

the Rivers Readers Project, the Itsekiri Language Project derives its funds exclusively

from voluntary contribution by the community.

3