Helping Students Learn Vocabulary

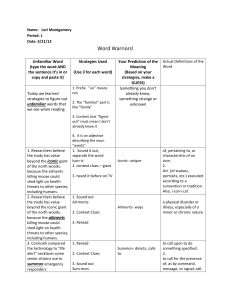

advertisement

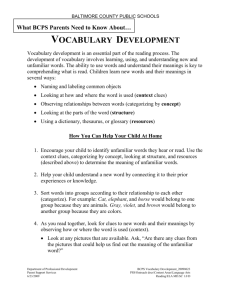

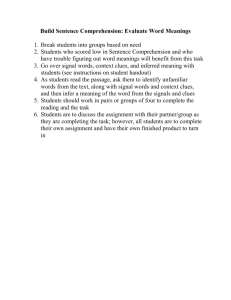

Helping Students Learn Vocabulary-Acquisition Skills The task of teaching vocabulary-acquisition skills usually falls to language arts teachers. This is a significant responsibility because formal learning—the kind of learning that students do in school—demands vocabulary knowledge. When you help students learn how to build their vocabularies, you help them succeed across the curriculum. This article examines the two major ways in which students acquire new vocabulary, the students for whom each way is best suited, and strategies for teaching vocabulary acquisition. Incidental Acquisition vs. Direct Study Students may acquire vocabulary in two ways: 1. Incidentally, through the conscious or unconscious use of context clues during independent reading and listening activities 2. Through direct instruction and study. Incidental Acquisition Incidental vocabulary acquisition is a common means of learning new vocabulary, especially for proficient readers. Students with strong reading skills who read a variety of texts may realize substantial gains in their vocabulary without direct instruction. High-risk students may also realize some incidental vocabulary gains through independent reading, however. Teachers should neither ignore nor rely solely upon incidental acquisition but rather seek to enhance its effectiveness with vocabulary logs, word walls and other techniques discussed below. Direct Study Of the two ways students acquire vocabulary, direct study is the more efficient, particularly for high-risk students with poor vocabularies. There are several reasons that students may fail to learn new vocabulary on their own: Lack of Independent Reading: High-risk students often have a history of reading difficulties. As a result, these students generally read less—and with less comprehension—than students with strong reading skills and rich vocabularies. The less students read, the fewer the opportunities to acquire new vocabulary. Inability to Use Context Clues: Students often lack the ability to find and use context clues to infer word meaning. Students may simply skip over unfamiliar words or, if the concentration of unfamiliar words is high, quickly become frustrated and stop reading entirely. Weakness of Context-Clue Vocabulary Acquisition: Even when students are able to use context clues to infer the meanings of unfamiliar words, the words may not become part of students' speaking, listening, or reading vocabularies. Studies show that students cannot recall an unfamiliar word whose meaning they have inferred unless they encounter the word repeatedly and within the same or a similar context. A Multifaceted Approach to Vocabulary Acquisition Because most classrooms contain a variety of types of students—high-risk, gifted or talented, and everything in between—teachers are wise to adopt a multifaceted approach to vocabulary acquisition. This approach provides direct instruction as well as opportunities for incidental learning. Here are some strategies for implementing the approach: Require independent reading: If your school does not already have a recommended reading list, help create one. Include high-interest, low-level books suitable for highrisk students as well as books that will challenge the gifted or talented. Then require students to read a certain number of books of their choice from the list. Students might provide feedback on their reading in a variety of ways: oral or written book reports, posters with plot summaries, performances of key scenes, or the creation of "book boxes"—cardboard boxes that contain objects key to the plot or characters in a book. Encourage the use of semantic maps: Semantic maps are graphic organizers that help students associate an unfamiliar word with familiar related words. To map the word noun, for example, draw a circle and write noun in the center of it. Then draw smaller circles around the central circle and fill each with a key related word, such as person, place, and thing. To complete the map, surround each outer circle with a series of subcircles, each containing an example of the related word, such as the name of a specific person, place, or thing. Then show the relationships by connecting all the circles with lines. Have students keep vocabulary logs: Require students to reserve a section of their journals or notebooks for listing, defining, and using new words that they learn during independent reading or in their classes. Have students copy the context in which they first encounter each word. Periodically collect students' logs and create opportunities for students to hear, see, and use the words in context. For example, you might use words from students' logs in classroom conversations. Have students create a "word wall"—a bulletin board displaying new words in sentences or graphic organizers—and require students to use the new words in compositions. Teach students the key word method: To use this mnemonic device, students think of an image that connects an unfamiliar word with a familiar key word that sounds similar or is contained within the target word. For example, to remember the word truculent, students might think of the key word truck and then draw or visualize a picture of a fierce-looking person driving a truck to represent the meaning of the word. Preteach unfamiliar vocabulary in reading assignments: Studies suggest that students must encounter a new word in print several times in order to remember its meaning. However, the number of encounters needed to learn the word is significantly reduced when students are taught the meaning of the word before encountering it in a reading assignment. http://www.glencoe.com/sec/teachingtoday/subject/vocab_acquisition.phtml