Cognitive factors behind second language acquisition

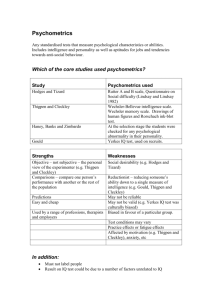

advertisement