Re-admission For Cellulitis, Survival And Mortality In The

advertisement

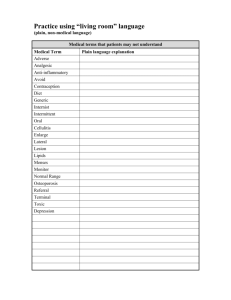

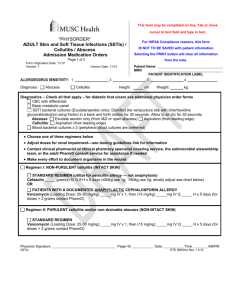

Introduction We previously defined cellulitis as a clinical syndrome consisting of erythema, oedema and warmth, which may be accompanied by acute pain or tenderness; and may be associated with overt or latent bacterial or fungal infection and constitutional disturbance.1 The epidemiology of cellulitis worldwide is unclear but is generally accepted as being between 1 to 4 per 1,000,000; to 2 per 1000 per year depending on the inclusion criteria 2, 3. In our previous paper, we described the rationale, design and characteristics of the North of England Cellulitis Treatment Assessment (NECTA).1 In brief, we measured the standard of in-patient care due to two treatment protocols for cellulitis in two hospitals in the North East of England and determined which one was associated with more robust outcomes.4 We studied 1337 admission episodes involving 568 patients between January 2001 and December 2003 as shown in Fig 1. Aim We aimed to determine the antibiotic treatment associated with the best patient outcomes 360 days from a hospital admission for cellulitis, by performing a head-to-head comparison of two commonly used antibiotic regimens. The first antibiotic regimen was empirical treatment with intra venous (IV) Flucloxacillin with further alteration to treatment as guided by microbiology sensitivities, whilst the second was IV Benzylpenicillin plus IV Flucloxacillin for 5 to 10 days. 1 Methods We sought and obtained the permission of the audit committees in the two hospitals. The audit proforma we used was based on the method previously described by Dong et al (2001) and identified 17 variables from the protocols being assessed.5 We related the variables to survival at different time points (Fig 2). Some of the 17 variables had well known associations with soft tissue infections. 2, 6, 7 Others were not clearly defined. They included lymphoedema, thrombophlebitis, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), injuries (Suppl Fig 1), recent surgery, (defined as any surgical procedure in the calendar month preceding admission); malignancy, ulceration, lower limb oedema, long-term use of drugs that caused salt and water retention, liver disease, cardiovascular disease, door-to-needle time for IV antibiotics (Fig 3), re-admission within 90 days of previous cellulitis admission, recent foreign travel, (defined as any trip outside the UK & Ireland in the calendar month preceding admission); being bed bound or immobile during the hospital admission being assessed, diabetes and obesity, (defined in as a body mass index [BMI] > 30). Statistics An independent statistician using SPSS 12.0.1 and R 1.9 software carried out all statistical analyses. 8 Results were expressed as mean (SD) or as percentages. Multivariate analysis was by stepwise logistic regression to test the independent role of each variable.9 Goodness-of-fit of each model was measured by the pseudo R2 measure, which is an indication of the proportion 2 of variance of the predicted outcome measure. Odds ratios were computed from regression parameters adjusted for all significant effects. 10 Results We found that 112 patients (19.7%) had died within 360 days (95% CI: 0.16 0.23). The mean time to death from first presentation for hospital admission was 100.89 days. The characteristics of those that had died within 360 days of presentation are presented in Table 1. Mortality Characteristics like animal bites or insect bites were not associated with any mortality in this study. We found the following to be statistically significant for mortality at the specified test statistic (z): Age (z=5.46, p<0.001) was a significant predictor of mortality at all time points except day 7. Re-admission within 90 days for cellulitis (z=3.96, p<0.001), previous MI (z=3.73, p<0.001) and penetrating injuries (z=3.48, p<0.001) were powerful independent predictors of mortality. Other factors that predicted mortality were long-term use of drugs that caused salt and water retention like phenelzine and steroids (z=3.38, p<0.001), being bed bound or immobile (z=3.42, p=0.001), liver disease or cirrhosis (z=2.96, p=0.003) and chronic lower limb oedema or chronic lymphoedema (z=2.49, p=0.01). IV Flucloxacillin was a significant negative predictor of mortality. (z=-3.79, p<0.001). The pseudo R2 for this model was 0.39. 3 Survival Fig 4 is an odds ratio of the factors that affected survival at 360 days. We reproduced this from our previous publication to put the predictors of mortality in the context overall survival.1 Previous myocardial infarction (MI) was a significant negative predictor of survival at 360 days (OR = 0.30, z = -3.38, p<0.001), but not for survival at other time points. In comparison, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), was a significant negative predictor of survival at 90 days (z=-2.31, p=0.02), but not at 360 days. Patient’s age was a significant negative predictor of survival at 90 days (z=-5.28, p<0.001), 30 days (z=-4.09, p<0.001) and 10 days (z=-2.59, p=0.01). Whilst penetrating injury (z=-4.06, p<0.001) and the presence of underlying malignancy (z= -2.39, p=0.02) were significant negative predictors at 90 days. Long-term use of drugs that caused salt and water retention like steroids or phenelzine negatively predicted survival at 30 days (z=-1.94, p=0.05) and 90 days (z=-4.68, p<0.001). Being bed bound or immobile was a significant negative predictor at 30 days (z=3.53, p<0.001), 10 days (z=-3.12, p=0.002) and 7 days (z=-3.19, p=0.001). IV Flucloxacillin was a significant predictor of survival at 30 days (z=2.37, p=0.02); 90 days and 360 days (z=4.92, p<0.001). Suppl Table 1 gives the Odds ratio (OR) and the test-statistic (z) for the statistically significant factors that affected survival at all time points studied. Discussion Mortality is a good measure of in-hospital care when looking at a disease process associated with hospital admission. 11, 12 In Table 1 we identified a 4 number of factors that seemed to be related to mortality in cellulitis admissions. The clinical features we report are similar to those reported by Dupuy et al (1999). 13 However, Dupuy et al focused mainly on presenting features like injuries, lymphoedema, venous insufficiency, weight and leg oedema. They did not investigate nor report the association of cellulitis with mortality, MI or liver disease. Similarly, Cox et al (1998) audited the management of cellulitis in two UK hospitals but did not comment on mortality or age. 14 In our study, we sought to relate cellulitis to mortality. We found age to be a profound predictor of mortality in cellulitis over time. Its predictive power at days 7 and 10 was not as strong as at days 30, 90 and 360. Conversely, the odds ratio of being bed bound increased over time, implying that being bed bound became less of a risk as time progressed. This may be because the patient would have in that time frame been appropriately treated for cellulitis, become more mobile and discharged from hospital. Table 1 also shows other factors that we associated with mortality but did not contribute to the predictive power of our model. Gender, for example, was not statistically significant though more females died. This finding agrees with the observation of McNamara et al (2007) who reported that the difference between the sexes was not statistically significant in a population-based study of lower limb cellulitis.2 Hypertension was more common in the group of patients that died in our study but was not a significant predictor. Obesity was more prevalent in the group that died but again, the difference was not statistically significant. The door-to-needle time for IV antibiotics was longer in the group of patients that died than for those that survived but was not a significant predictor of mortality (Fig 3). The majority of those that received IV antibiotics more that 5 50 hours from presentation were those who were admitted into hospital for other conditions mainly orthopaedic surgery and developed cellulitis as a complication of treatment. In our study, survival was worse for elderly patients with cardiovascular disease and penetrating injury, who were bed bound and did not receive IV flucloxacillin (Suppl Fig 3). The addition of IV benzylpenicillin to IV flucloxacillin was not associated with a survival advantage (Suppl Fig 2) when compared to IV flucloxacillin alone (Suppl Fig 3). This finding is similar to that of Leman et al (2005) who reported that the addition of benzylpenicillin to flucloxacillin did not significantly alter patient outcomes nor patients’ perception of treatment in cellulitis.15 One possible reason for this finding could be that the most common organism isolated from the microbiology samples of the NECTA patients was Staphylococcus aureus. This finding however contradicts the Spanish multi-centre mortality study in cellulitis (STIMG) in which amoxicillin with clavulanate was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic and in which the investigators reported a mortality of 10.4%.16 The STIMG investigators limited their observations to 30 days but in our study, most of the deaths occurred later than this (Fig 2). Early mortality in NECTA using the same timeframe as STIMG was 9.5%. Fig 5 show the Kaplan-Meier curves of the other antibiotic treatments identified by our study as compared to the two main antibiotic treatments assessed. Fig 5 seems to suggest that Cephalosporin worsened survival. This contradicts a similar study of the Emergency Departments of five Canadian hospitals by Dong et al (2001) in which better patient outcomes were reported with cephalosporins. 5 6 Survival for the Cephalosporin group in our study was probably worse because they did not receive Flucloxacillin in addition to Cephalosporin. There were a few confounders in our model that could weaken the validity of the predictions. First, to avoid multi-co-linearity, we omitted readmission from the odds ratio for survival. We thus prevented the inter-dependence of the other characteristics and readmission causing the occurrence of a type 2 error. Second, patients that were bed bound or immobile had an average door-to-needle time of 69 hours but this was 16 hours for those that were not bed bound. Thus patients that were bed bound in NECTA may have had a worse outcome because they did not receive IV antibiotics in time. Third, mortality in our study measured only mortality in acute hospital admissions and not mortality due to the prevalence of cellulitis in the North East of England. During the study period, about the same number of patients were seen in the Accident & Emergency department and treated as day cases with follow-up oral antibiotics. Further, an unknown number with mild-to-moderate disease were being treated within the community by general practitioners as is the practise in many parts of the world.17, 18 Thus, those that were admitted into the NECTA hospitals may have been selectively biased towards community and outpatient treatment failures or severe disease. For this reason, our findings may only apply to cellulitis that result in an acute hospital admission. We agree with Stevens et al (2005) who argue that irrespective of the risk profile of the patient that cellulitis should not be allowed to progress towards systemic infection and sepsis. 19 We report a 19.7% chance of death within 360 days of an acute admission for cellulitis whether or not it is 7 complicated by systemic infection and sepsis. Our figures suggest that stratifying a patient’s risk of death with a composite of the predictors of mortality followed by the early administration of IV antibiotics would improve 360-day survival. Finally, in interpreting these figures, we did not actively seek to confirm that the high number of patients lost to follow up (Fig 1) or those discharged into the community had not died since the admission we assessed. We may thus have under-estimated the final number of deaths due to cellulitis admissions at 360 days. Limitations This was a retrospective study. The endpoints were not pre-specified and a dedicated research team did not administer the treatments assessed. The population studied was not homogeneous and that might have influenced the reported outcomes. Our findings may at best be regarded as hypothesis forming and should provide the background for a randomised clinical trial. Conclusion The risk of death or survival in patients admitted with cellulitis can be recognised from the clinical features during in-hospital treatment. They include: age, re-admission for cellulitis, presence of penetrating injury, chronic lower limb oedema, liver disease, history of previous MI, history of long term use of steroids continuing into the acute admission for cellulitis and being bed bound or immobile during that hospital admission. We report a death rate of 8 19.7% at 360 days from the initial presentation. We also report that empirical IV Flucloxacillin alone was superior to other antibiotics or combination of antibiotics in NECTA. Competing Interests: None declared Acknowledgements: None. 9 Table 1. Characteristics Of Those That Died “Risk” factor Age Mean/Percentage of those alive after 360 days 55.3 Mean/Percentage of those dead after 360 days 76.9 Males 52.8 40.0 Previous MI Hyperlipidaemia CABG Hypertension Peripheral vascular disease Any CVD factor 13.6 14.8 0.8 30.6 4.5 38.6 48.8 20.0 2.5 60.0 17.5 76.3 Toeweb Maceration Liver disease Bed bound/immobility Re-admission within 90 days Ulceration Lower limb oedema Recent foreign travel Long term use of drugs Other risk factors 12.1 0.8 7.6 15.0 12.5 36.3 8.1 9.8 24.6 26.9 4.2 6.3 10.6 25.0 56.3 2.5 24.4 10.0 Blunt injury Penetrating injury Minor injury Recent surgery Animal bite Insect bite Other injury Any of the above injuries 21.5 5.3 17.5 8.0 7.6 6.4 16.3 43.2 17.5 07.5 13.8 8.8 0.0 0.0 12.5 30.0 Diabetes Obese Lymphoedema DVT Thrombophlebitis Malignancy Other 11.3 54.4 15.1 1.5 12.8 4.9 11.4 25.0 56.0 25.0 6.3 23.8 21.3 32.5 Antibiotic Benzylpenicillin Flucloxacillin Cephalosporin Clindamycin Other 68.3 81.5 6.0 3.8 42.6 35.0 46.3 20.0 2.5 55.0 Other Treatments Limb Elevation Compression for leg ulceration, venous insufficiency or oedema Terbinafine cream for tinea pedis 24.3 12.5 21.8 20.5 15.3 12.8 Time to antibiotics 23.2 hours 56.9 hours Patient characteristics Cardiovascular disease Risk factors Injury Co-morbidities 10 Fig 1: Flow Chart of NECTA Admissions Assessed (n=1,337) Ineligible Re-admissions (n=592) Case notes not located (n=75) Audit Population (n=670) Lost to follow-up (n=102) Deaths within 360 days (n=112) Survivors at 360 days (n=456) Factors Affecting Death Factors Affecting Survival -Chronic lower limb oedema -Age < 40 -IV Flucloxacillin -Previous MI -Penetrating injury -Liver disease -Long term steroids -Re-admission within 90 days -Being bed bound or immobile 11 Fig 2: Survival 12 Fig 3: Door-To-Needle Time For IV Antibiotics 13 Fig 4: Odds Ratio of Factors Influencing Survival At 360 Days 14 Fig 5: Kaplan-Meier Curves Of Antibiotic Treatments 15 References 1 Tan RD, Newberry D, Arts G, Onwuamaegbu ME. The design, characteristics and predictors of mortality in the North of England Cellulitis Treatment Assessment (NECTA). Int J Clin Pract 2007; 61: 1889 - 1893 2 McNamara DR, Tleyjeh IM, Berbari EF, Lahr BD, Martinez JW, Mirzoyev SA, Baddour LM. Incidence of lower-extremity cellulitis: a population-based study in Olmsted county, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82: 817-821 3 Goettsch, W.G., J.N. Bouwes Bavinck, and R.M. Herings, Burden of illness of bacterial cellulitis and erysipelas of the leg in the Netherlands. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006; 20: 834-839. 4 Berwick D. Measuring NHS Productivity. How much health for the pound, and not how many events for the pound. BMJ 2005; 330: 975-976 5 Dong SL, Kelly KD, Oland RC, Holroyd BR, Rowe BH. ED management of cellulitis: A review of five urban centers. American J Emerg Med 2001; 19: 535-540 6 Bisno AL, Stevens DL. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N Eng J Med 1996; 334: 240 –245 7 Low DE, McGeer A. Skin and soft tissue infection: necrotizing fasciitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 1998; 11: 119 – 123 8 Field A. Discovering Statistics using SPSS for Windows. Sage, London 2000 9 Cramer D. Advanced quantitative data analysis. Open University Press, Maidenhead. 2003 10 Wetherill GB. Intermediate statistical methods. Chapman & Hall, London. 1981 Mason A, Goldacre M, Daly E. Using case fatality rates as a health outcome indicator – a literature review. Report to the Department of Health. Oxford: National centre for Health Outcomes Development, 2000 11 12 Lakhani A, Coles J, Eayres Daniel, Spence C, Rachet B. Creative use of existing clinical and health outcomes data to assess NHS performance in England: part 1 – performance indicators closely linked to clinical care. BMJ 2005; 330: 1426 – 1431 13 Dupuy A, Benchikhi H, Roujeau J, Bernard P, Vaillant L, Chosidow O, Sassolas B, Guillaume J, Grob J, Bastuji-Garin S. Risk factors for erysipelas of the leg (cellulitis): case-control study. BMJ 1999; 318: 1591 - 1594 14 Cox NH, Colver GB, Paterson WD. Management and morbidity of cellulitis of the leg. J R Med 1998; 91: 634-637 15 Leman P, Murkherjee D. Flucloxacillin alone or combined with benzylpenicillin to treat lower limb cellulitis: A randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med J 2005; 22: 342- 346 16 Salgado OF, Villar JJ, Hidalgo CA, Villalobos SA, de la Torre LJ, Aquilar GJ, da Rocha CI, Garcia OMA, Nuno AE, Ramos CC. Martin PM. Epidemiological characteristics and mortality risk factors in patients admitted in hospitals with soft tissue infections. A multicentric STIMG (Soft Tissue Infections Malacitan Group) study results. An Med Interna 2006; 23: 310-316 17 Vinh, D.C., Embil, J.M. Rapidly progressive soft tissue infections. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5: 501513 16 18 Hepburn, M.J., Dooley, D.P., Skidmore, P.J., Ellis, M.W., Starnes, W.F., Hasewinkle, W.C. Comparison of short-course (5 days) and standard (10 days) treatment for uncomplicated cellulitis. Arch Int Med 2004; 164: 1669-1674 19 Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Everett HF, Dellinger P, Goldstein EJC, Gorbach SL, Hirschmann JV, Kaplan EL, Montoya JG, Wade JC. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41: 1373 –1406 17