Lecture 1: Bridging Quali & Quanti

advertisement

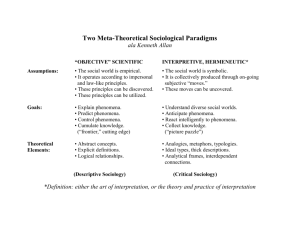

北京师范大学 教育研究中的比较―历史方法 Lecture 1 The Essence of Comparative-Historical Studies: Bridging Quantitative and Qualitative Methods in Educational Research A. Max Weber’s Aporia for researchers of the social sciences 1. "Sociology is a science concerning itself with interpretive understanding of social action in order thereby to arrive at a causal explanation of its course and consequence. We shall speak of 'action' insofar as the acting individual attaches a subjective meaning to his behavior. …Action is 'social' insofar as its subjective meaning takes account of the behavior of others and is thereby oriented in its course." (Weber, 1978, p. 4) 2. Statements of the problem: a. Problem of interpretive sociology: Weber stipulates that sociology should strive to provide "interpretive understanding" of the "subjective meaning" underlying social action. b. Problem of positive sociology: Weber at the same time stipulates that sociology should strive to render "causal explanation of course and consequences of social action. c. Problem of micro- and macro-sociology: How can reciprocity of subjective meanings of different individuals participating in social interaction be possible? B. Juxtaposing the Natures and Features of Quantitative and Qualitative Methods in Educational Research Objects of Inquiry Aims of Inquiry Quantitative Method Natural phenomena; Pre-existing & given reality; Natural facts Regularities; Universal and exhaustive laws of causal explanation Orientations of Inquiry Objectivity; Value-neutrality Methodological Approach Method of Inquiry Logical-positivism; Empiricism Scientific experiments; Empirical survey Mode of Explanation Causal explanation in: Nomological-induction model; Probabilistic-deductive model W.K. Tsang Historical-Comparative Method in Ed Research Qualitative Method Cultural phenomena; Man-made & constructed reality; Artifacts Meanings & significances; Subjective meanings; Social meanings; Cultural meanings Subjectivity; Value-laden & culturally significant Empathetic understanding; Interpretive approach Ethnography; Hermeneutics; Psycho-analysis Intentional explanation Rational-choice model; Interpretive-purposive mode 1 C. Three Interpretations of Weber’s Aporia 1. Alfred Schutz in begins his major scholarly work The Phenomenology of the Social World (1932/1967) the chapter entitled “The Statement of Our Problem: Max Weber’s Basic Methodological Concepts.” He defines “Max Weber’s initial statement of the goal of interpretive sociology ” as “to study social behavior by interpreting its subjective meaning found in the intentions of individual individuals. The aim, then, is to interpret the actions of individuals in the social world and the ways in which individuals give meaning to social phenomena. But to attain this aim, it does not suffice either to observe the behavior of a single individual or to collect statistics about the behavior of groups of individuals, as a crude empiricism would have us to believ. Rather, the special aim of sociology demands a special method in order to select the materials relevant to the particular questions it raise.” (Scgutz, 1967, Pp.6-7) 2. Jurgen Habermas in his book On the Logic of the Social Sciences (1988/1967) also starts with Weber’s aporia. Habermas underlines that “The definition of sociology that Weber gives in the first paragraphs of Economy and Society applies to method: ‘Sociology is a science concerning itself with interpretive understanding of social action in order thereby to arrive at a causal explanation of its course and consequence’ We may consider this sentence as an answer to the question, How are general theories of social action possible? General theories allow use to derive assumptions about empirical regularities in the form of hypotheses that serve the purpose of explanation. At the same time, and in contradistinction to natural processes, regularities of social action have the property of being understandable. Social action belongs to the class of intentional actions, which we grasp by reconstructing their meaning.” (Habermas, 1988/1967, Pp. 10-11) 3. Georg H. von Wright in his book Explanation and Understanding (1971) underlines, “It is … misleading to say that understanding versus explanation marks the difference between two types of scientific intelligibility. But one could say that the intentional or nonintentional character of their objects marks the difference between two types of understanding and of explanation.” (von Wright, 1971, p.135) Instead he distinguishes two traditions of explanation prevailing in the methodology of history and social sciences, namely causal/nointentional and intentional explanation: a. Causal explanation: It refers to the mode of explanation, which attempt to seek the sufficient and/or necessary conditions (i.e. explanans) which antecede the phenomenon to be explained (i.e. explanandum). Causal explanations normally point to the past. ‘This happened, because that had occurred’ is the typical form in language.” (von Wright, 1971, p. 83) It seeks to verify the antecedental conditions for an observed natural phenomenon. b. Teleological explanation: It refers to the mode of explanation, which attempt to reveal the goals and/or intentions, which generate or motivate the explanadum (usually an action to be explained) to take place. “Teleological explanations point to the future. ‘This happened in order that that should occur.’” (von Wright, 1971, p. 83) D. Debate between Methodological Individualism and Methodological Collectivism 1. The reductionism and methodological individualism a. F.A. Hayek: "There is no other way toward an understanding of social phenomena but through our understanding of individual actions direct toward other people and guided by their expected behavior." (quoted in Lukes, 1994, p. 452) W.K. Tsang Historical-Comparative Method in Ed Research 2 b. Karl R. Popper: "All social phenomena especially the functioning of all social institutions, should always be understood as resulting from the decisions, actions, attitudes, etc. of human individuals, and …we should never be satisfied by an explanation in terms of so-called collectives." (quoted in Like, 1994, p. 452) c. J.W.N. Watkins: "I am an advocate of …the principle of methodological individualism. According to this principle, the ultimate constituents of social world are individual people who act more or less appropriately in the light of their dispositions and understanding of their situation. Every complex social situation or event is the result of a particular configuration of individuals, their dispositions, situations, beliefs and physical resources and environment. There may be unfinished or halfway explanations of large-scale social phenomena (say, inflation) in terms of other large-scale phenomena (say, full employment); but we shall not have not arrived at rock-bottom explanations of such large-scale phenomena until we have deduced an account of them from statements about the dispositions, beliefs, resources, and interrelations of individuals." (Quoted in Luke, 1994, p. 452) d. Jon Elster: "By this (methodological individualism) I mean the doctrine that all social phenomena ― their structure and their change ― are in principle explicable in ways that only involve individuals ― their properties, their goals, their beliefs and their actions. Methodological individualism thus conceived is a form of reductionism. To go from social institutions and aggregate patterns of behavior to individuals is the same kind of operation as going from cells to molecules," (Quoted in Wright, 1992, p. 111) 2. Classical sociologists’ conception of methodological collectivism a. Emile Durkheim's methodological collectivism i. Sociology is "the study of social facts" (Durkheim, 1982/, p. 50) ii. "A social fact is any way of acting, whether fixed or not, capable of exerting over the individual an external constraint; or which is general over the whole of a given society whilst having an existence of its own, independent of its individual manifestation." (1982, p.59) c. Education as a social fact: i. "This definition of a social fact can be verified by examining an experience that is characteristic. It is sufficient to observe how children are brought up. If one view the facts as they are and indeed as they have always been, it is patently obvious that all education consists of a continual effort to impose upon child ways of seeing, thinking and acting which he himself would not have arrived at spontaneously. " (1982, p. 53) ii. "Each society sets up a certain idea of man, of what he should be, as much from the intellectual point of view as the physical and moral; that this ideal is, to a degree, the same from all citizens, that beyond a certain point it becomes differentiated according to the particular milieux that every society contains in its structure. It is this ideal at the same time one and the various, that is the focus of education. Its function, then, is to arouse in the child : (1) a certain number of physical and mental states that the society to which he belongs considers should not be lacking in any of its members; (2) certain physical and mental states that the particular social group (caste, class, family, profession) considers, equally, ought to be found among all those who make it up. Thus it is society as a whole and each particular social milieu that determine the ideal that education realizes. Society can survive only if there exists among its members a sufficient degree of W.K. Tsang Historical-Comparative Method in Ed Research 3 homogeneity; education perpetuates and reinforces this homogeneity by fixing in the child, from the being, the essential similarities that collective life demand. But on the other hand, without a certain diversity all co-operation would be impossible ; education assures the persistence of this necessary diversity by being itself diversified and specialized." (2006, p.79-80) e. "Sociology can…be defined as the science of institutions, their genesis and their functioning." (Durkheim, 1982, p. 45) D. The Hermeneutical Arc: Institutionalization of Social Interaction 1. Habermas’ solution to the General Theory of Social Action: a. At the beginning of his book On the Logic of the Social Sciences, Habermas poses the fundamental problem “How are general theories of social action possible?” (Habermas, 1988/1967, P. 11) b. Subsequently, Habermas provides the following solution to the problem: “In the terminology of Max Weber,…we can say that in a certain way sociology presupposes the value-interpretation of the hermeneutic sciences, but is itself concerned with cultural tradition and value-system only insofar as they have attained normative power in the orienting of action. Sociology is concerned only with institutionalized values. We can now formulate our question in a more specific form: How are general theories of action in accordance with institutionalized values (or prevailing norms) possible?” (Habermas, 1988, p. 75) 2. The institutionalists’ solutions E. Comparative-Historical Method on Institutions: Big Structures, Large Process and Hugh Comparisons W.K. Tsang Historical-Comparative Method in Ed Research 4