Address from Fergal Tobin, President of Clé, the Irish Publishers

advertisement

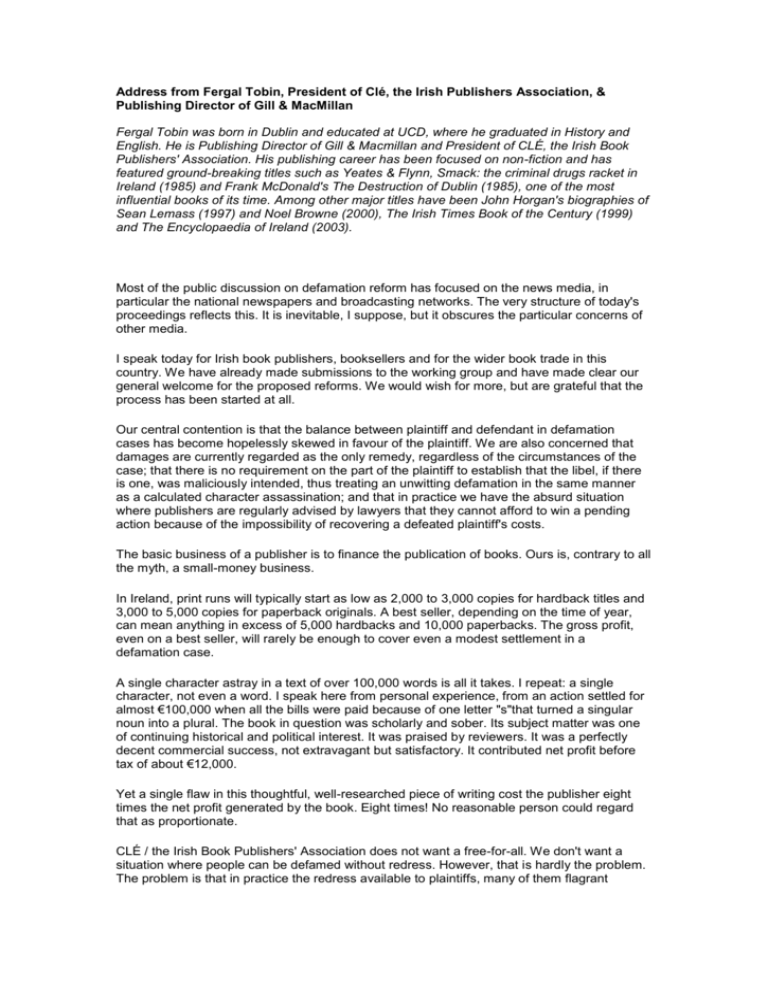

Address from Fergal Tobin, President of Clé, the Irish Publishers Association, & Publishing Director of Gill & MacMillan Fergal Tobin was born in Dublin and educated at UCD, where he graduated in History and English. He is Publishing Director of Gill & Macmillan and President of CLÉ, the Irish Book Publishers' Association. His publishing career has been focused on non-fiction and has featured ground-breaking titles such as Yeates & Flynn, Smack: the criminal drugs racket in Ireland (1985) and Frank McDonald's The Destruction of Dublin (1985), one of the most influential books of its time. Among other major titles have been John Horgan's biographies of Sean Lemass (1997) and Noel Browne (2000), The Irish Times Book of the Century (1999) and The Encyclopaedia of Ireland (2003). Most of the public discussion on defamation reform has focused on the news media, in particular the national newspapers and broadcasting networks. The very structure of today's proceedings reflects this. It is inevitable, I suppose, but it obscures the particular concerns of other media. I speak today for Irish book publishers, booksellers and for the wider book trade in this country. We have already made submissions to the working group and have made clear our general welcome for the proposed reforms. We would wish for more, but are grateful that the process has been started at all. Our central contention is that the balance between plaintiff and defendant in defamation cases has become hopelessly skewed in favour of the plaintiff. We are also concerned that damages are currently regarded as the only remedy, regardless of the circumstances of the case; that there is no requirement on the part of the plaintiff to establish that the libel, if there is one, was maliciously intended, thus treating an unwitting defamation in the same manner as a calculated character assassination; and that in practice we have the absurd situation where publishers are regularly advised by lawyers that they cannot afford to win a pending action because of the impossibility of recovering a defeated plaintiff's costs. The basic business of a publisher is to finance the publication of books. Ours is, contrary to all the myth, a small-money business. In Ireland, print runs will typically start as low as 2,000 to 3,000 copies for hardback titles and 3,000 to 5,000 copies for paperback originals. A best seller, depending on the time of year, can mean anything in excess of 5,000 hardbacks and 10,000 paperbacks. The gross profit, even on a best seller, will rarely be enough to cover even a modest settlement in a defamation case. A single character astray in a text of over 100,000 words is all it takes. I repeat: a single character, not even a word. I speak here from personal experience, from an action settled for almost €100,000 when all the bills were paid because of one letter "s"that turned a singular noun into a plural. The book in question was scholarly and sober. Its subject matter was one of continuing historical and political interest. It was praised by reviewers. It was a perfectly decent commercial success, not extravagant but satisfactory. It contributed net profit before tax of about €12,000. Yet a single flaw in this thoughtful, well-researched piece of writing cost the publisher eight times the net profit generated by the book. Eight times! No reasonable person could regard that as proportionate. CLÉ / the Irish Book Publishers' Association does not want a free-for-all. We don't want a situation where people can be defamed without redress. However, that is hardly the problem. The problem is that in practice the redress available to plaintiffs, many of them flagrant opportunists and gold diggers, is out of all proportion to the offence caused. It is against this background of bitter experience that we have responded to the report of the working group. We welcome item 1 in the working group's summary of recommendations which proposes a defence of "reasonable publication" and would add only that this definition should provide for a mitigating plea of due care on the part of author and publishers in the preparation of a book. In this connection, recommendation 10 - proposing a fast-track, no jury process in appropriate cases, a kind of small claims court - is especially welcome. We also welcome the intellectual assumption behind recommendation 12 - that the defence of fair comment should be re-named that of "honest opinion", although quite how that might work in practice would depend on very careful legislative draughtsmanship and possibly on test cases in the courts. The proposal - number 17 in the recommendations - that defamation actions in most circumstances be statute barred after one year and absolutely after six years, if carried into law will rid us of a particularly scandalous anomaly. The reiteration of the Law Reform Commission's recommendation that an offer of amends, whether by apology or otherwise, should not be construed as an admission of guilt and should be taken into account in mitigation of damages would be a major step forward. However, a step backward would be the LRC's recommendation that in some circumstances yet to be defined, a defamation action might survive the death of the plaintiff. We realise that it is thus in some jurisdictions - Italy, for example - but it seems to us to be unwise: leaving aside the temporal absurdity involved, in practice it could be a charter for frivolous litigation, even unto the seventh generation. We note that it is recommended that the present law of criminal libel be replaced by a new offence of "publication of gravely harmful statements" and that calculated malice in the material complained of should be a condition for such a prosecution. We cannot, however, understand why the principle of malice should not be extended to other defamation pleadings, all the more so when it is now recommended that a two-tier system for the tort of defamation be established: fast-track before a single judge in a non-jury court on the one hand and the traditional Circuit Court and High Court actions on the other. If this proposal is enacted, plaintiffs who ignore the fast-track remedy in favour of traditional proceedings should be required to establish malice on the part of the defendant in order to succeed at this level. Here is a perfect opportunity to come closer to Boston than Berlin and to adapt this requirement of United States law into our own. And while we are at it, why not require plaintiffs who insist on by-passing the fast-track procedure in order to have their day in the High Court to show some evidence to the court that they can cover the full costs of the action in the event of their losing? Let them gamble with their own money rather than with the defendant's. Otherwise justice is denied. I have known many cases where a defence could not be mounted because of the certainty that a defeated plaintiff would be unable to discharge our costs. As has often been said, defamation is for the very rich and the very poor. We welcome the proposal to introduce a defence of innocent defamation which would mean that printers, booksellers, wholesalers and distributors would no longer be joined to libel actions. The fact that they can be so joined at present is a patent absurdity and an anachronism. As I said, publishing is a business but it is not just any old business. The presence of an indigenous publishing industry, one animated by Irish concerns, sensitive to Irish culture and mores and alert to the nuances of our society is all the more valuable given the immense gravitational pull of what Myles na Gopaleen used to call "the friendly kingdom adjacent". Most Irish book publishers are small businesses. Most members of CLÉ could not survive the sort of hit I described earlier. And so we have the chill effect: don't go there, don't publish in that area, don't turn over that stone. I knew for almost twenty years that many of the dramatis personae at the Moriarty and Flood-Mahon tribunals were deeply compromised. I did not go there. We have all not been going there for too long. We don't go there because we don't want to go out of business. And that is the reality of the present law. The penalties are so great that book publishers can't afford the least slip. One distinguished publisher nearly went that way in the 1980s. It is a matter of pure good luck, combined with the chill effect, that a successful defamation action has not yet bankrupted an Irish book publisher. But it will happen sooner or later if these reforms - and I would hope, more to follow - don't go through. Is that really the kind of country we want?