compressed adversaries

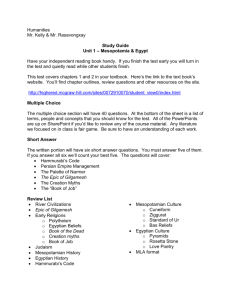

advertisement

Chapter 2 Notes The Rise of Civilization: The Art of the Ancient Near East The change from hunter - gatherer to the stable life of a farmer herder caused such change in human society that its impact cannot be overstated. It was so great it has been called the Neolithic Revolution. This change first took place in Mesopotamia a Greek word meaning “the land between the rivers” (Tigris and Euphrates). This is the core of an area called the Fertile Crescent, a land mass that forms a huge arc from the mountainous border between Turkey and Syria through Iraq to Iran’s Zagros Mountains. It was here that man first learned how to use the wheel and the plow and how to control floods and construct irrigation canals. The land became a giant oasis. It is the land of the Bible and the presumed locale of the Biblical Garden of Eden. The region gave birth to three of the world’s great modern faiths - Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Because of this the area has always been of interest to historians. It was not until the 19th century that systematic evacuations opened the world’s eyes to the extraordinary art and architecture of the region. The flurry of activity was largely motivated by Christians wanting to discover the places of the Bible to counteract the “Higher Criticism” by those trying to explain away the Bible. The great European museums began acquiring Mesopotamian artworks after the first discoveries. Their directives were the same - obtain as many well preserved art works as you can while spending the least amount of time and money as possible. Soon the North American museums followed. Great cities of the Bible were discovered; Ninevah of the Assyrians, Babylon and the Royal Cemetery of Ur. Sumerian Art The discovery of the treasures of ancient Ur, the city of Abraham, brought the Sumerians to the world stage after 4000 years. The Sumerians transformed the vast river valley into the Fertile Crescent of the ancient world. In the forth millennium the Sumerian established the first great urban communities and developed the earliest known writing system. City-States Ancient Sumer was not a unified nation but rather was made up of a dozen or so citystates, each under the protection of a different deity. The rulers were god’s representatives on earth and stewards of their earthly treasure. The rulers and priests directed all communal activities including canal construction, crop collection, and food distribution. Agriculture was developed to a point that only a portion of the population had to produce food. This enabled the rest of the population to be organized into a labor force that allowed specialization. Labor specialization is the hallmark of the first complex urban societies. Activities that once were individualized were now institutionalized, things such as defense against nature and against enemies. People could specialize in manufacturing, trade, administration, and skilled arts. City Planning and Religion The local god’s temple formed the cities monumental nucleus. It was the focus of religious practice and the administrative and economic center. The temple staff had both religious and administrative duties. Writing The oldest known written documents are Mesopotamian records of administrative acts and commercial transactions. This was done by creating pictographs (simplified pictures standing for words) into soft clay tablets with a sharp cool called a stylus. The tablets were written with pictorial signs from the top down and were arranged in boxes that read from right to left. By 3000 -2900 BC the signs were further simplified to a group of wedge-shaped (cuneiform) signs. This marked the beginning of writing as historians strictly define it. By 2600 BC cuneiform texts were sophisticated enough to express complex grammatical constructions. The White Temple of Uruk One of the best preserved examples of Sumerian temple architecture is the 5000 year old White Temple named for its white washed walls. It was built several centuries before the pyramids and says much about the Sumerian desire to provide monumental settings for worship. The Temple stood on top of a ziggurat or high platform, 40 feet above street level. The stair way led up the side but did not end up at the top in front of the temple doors as it was aligned in other cultures. The corners of the temple are aligned to the points of the compass. It was 61’x16, met for the priests and perhaps a select few, but not the masses. The temple had several chambers, the largest was the cella or central chamber where they would wait for the gods to descend from the heavens and appear in the cella. It is not certain if the temple had a roof. The Warka Vase This vase is the first great narrative relief sculpture known. It depicts a religious festival in honor of the goddess Inanna, the goddess of love and war. The sculpture divided the vase into three bands called registers or friezes. This way of telling a story was a new kind of composition that is in use even today. The lowest band is of ewes and rams in the strict profile. This is above crops and a wavy line representing water. These and the alternating animals were staples of the Sumerian economy and were associated with fertility, a procession of naked men fill the central band. The men carry baskets and jars overflowing with the abundance of the land to be presented as an offering. The men are a composite of frontal and profile views, with large staring frontal eyes in profile heads. The anatomical parts depicting gender are not avoided. Art historians call this early approach to representation conceptual as opposed to optical, because artists who used it did not record the immediate, fleeting aspects of the figures. Instead they rendered the human bodies distinguishing and fixed properties. The fundamental forms of figures, not their accidental experience, dictated the artist’s selection of the composite view as the best way to represent the human body. The top tallest band depicts a tall female figure with a tall horned headdress. A smaller nude man is bringing an offering to be deposited at the goddess’s shrine. Another large partially clothed male figure, referred to as a priest-king; the size of the two figures indicate their importance. This convention is called hierarchy of scale. Perhaps this depicts the marriage between the goddess and the ruler, reaffirming the leader’s exalted position in society. Perpetual Worshipers from Eshnunna (Sumerian Votive Figures) Further insight into Sumerian religious beliefs and rituals comes from a cache of figures reverently buried beneath the floor of a temple at Eshnunna. What can we tell about these figures? (Sculpture Handout) These are Votive Figures. A votive offering is a gift of gratitude to a deity usually made in fulfillment of a vow. Carved soft gypsum is an inexpensive material in which gender is distinguished. Hands clasped Eyes large and inlaid with shell and black limestone. What does the open-eyed stare mean? The Standard of Ur In the 3rd millennium BC the leading families of Ur buried their dead in vaulted chambers beneath the earth. Along with riches and objects of expensive materials, dozens of bodies were found in the tombs of the richest. It is believed that these were musicians, servants, charioteers, and soldiers sacrificed in order to accompany the “kings and queens” in the after life. The most significant work from an art historical point of view found in these tombs of Ur was the so called Standard of Ur. A rectangular box with sloping sides inlaid with shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone. Originally thought to have been mounted on a pole, Leonard Wooly thought it was a kind of military standard, hence the nickname. One side is called the “War Side” and the other the “Peace Side.” But they may have been a single narrative. The space is divided into three horizontal bands on each side. The narrative reads left to right and bottom to top. On the war side, four mule-drawn four wheeled chariots roll over enemies. Above foot soldiers lead away captured foes. In the upper register, soldiers present bound captives, stripped naked to degrade them, to a king like figure, who has stepped out of his chariot. What visual tells us who the king is? In the lowest band on the peace side, men carry provisions, possibly war booty, on their backs. Above attendants bring animals, perhaps as spoils of war, and fish for the Great Banquet depicted on the upper band. There dignitaries and the king feast while a Lyre player and singer entertain the group. The absence of written narrative makes it difficult to pinpoint a specific event or character, but it is another early example at narrative. Bull Headed Lyre The musical instrument depicted here is a Bull Headed Lyre that is could be the one depicted on the standard of Ur. The bulls head is made of wood and covered with gold. The hair and beard are lapis lazuli. The narrative on the sound box of the Lyre depicts human headed bulls. Imaginary composite creatures are common in ancient Near East art and Egypt. A heroic figure embraces the two man bulls in a Heraldic Composition (Symmetrical on either side of a central figure. His body is a composite view as is scorpion man on the bottom. The animals are in profile. The sound box is a rare example of the recurring theme in both literature and art of animals acting like people. Later examples are Aesop’s Fables in ancient Greece, medieval bestiaries, and Walt Disney’s cartoon animal actors. Head of an Akkadian Ruler In 2334 BC the city states of Sumer came under the domination of a great ruler, Sargon of Akkaid. Under Sargon, whose name means “true king,” and his followers, the Akkadians introduced a new concept of royal power based on unswerving loyalty to the king rather than the city state. During the rule of Sargon’s grandson Naram -Sin, governors of cities were considered mere servants of the king, who, in turn called himself, “King of the Four Quarters. A magnificent copper head from this period embodies the new concept of absolute monarchy. This head was part of a larger statue that did not survived. It was possibly destroyed when the Medes sacked Ninevah in 612 BC. There are signs of mutilation beyond a mere toppling. To show domination the conquering enemy gouged out the eyes (made of precious stones perhaps), broke off the lower part of the beard, mashed the nose, and slashed the ears of this royal portrait. In spite of this the authority and dignity of the king still is evident. There is a masterful balance of naturalism and abstract patterning on the beard, showing great skill in depicting the different textures and sensitivity to formal pattern. Another amazing fact is that this is the earliest known, great monumental work of life-size, hollow-cast, metal sculpture. Victory Stele of Naram-Sin The godlike sovereignty of the Akkadian kings is evident in this victory stele of Naram Sin the grandson of Sargon. The victory commemorates his victory over the Lullupi people of the Eastern Iranian Mountains. It is inscribed twice, once in honor of NaramSin, and once for the Elamite king who captured Sippar (the city of Naram Sin?), in 1157 BC, and took the stele as booty back to Suza where it was found. On the stele Naram-Sin leads his victorious army up the slopes of a wooded mountain. His routed enemies fall, flee, die, or beg for mercy. The king stands alone, far taller than his men, treading on the bodies of two fallen Lullupi. He wears a horned helment signifying divinity-- this is the first time that a king appears as a god in Mesopotamian art. At least three favorable stars shine in approval. By storming the mountain, Naram-Sin appears to be climbing to heaven. This arrogance and conceit is common among the great warrior peoples of Mesopotamia. His troops march up the mountain behind him in orderly files, suggesting the discipline and organization of the king’s forces. The enemy in contrast is in disarray, in various agonizing positions. What do we notice about the figures? Composite - frontal horns, profile head, frontal torso, profile legs. This is the first landscape in Near Eastern art since the Catal Hoyuk mural. The figures are placed on successive tiers rather than on horizontal registers as was the rule in Mesopotamian and Egyptian art. The Ziggurat of Ur Around 2150 BC, the Gutians brought an end to Akkadian power. The cities of Sumer united and drove out the invaders and established a Neo-Sumerian state ruled by the kings of Ur. Historians call this period the third dynasty of Ur. It was during this period that the gigantic Ziggurat of Ur was constructed. The Ziggurat of Ur was built about 1000 years after the White Temple at Uruk and was much grander. The base is a solid mass of mud brick 50 feet high. The builders used baked brick laid in bitumen, an asphalt like substance for the facing of the entire monument. Gudea The most conspicuous preserved sculptural monuments on the Neo-Sumerian age art portraits of Gudea of Lagash. His statutes show him seated or standing, hands tightly clasped, head shaven, sometimes wearing a woolen brimmed hat, and always dressed in a long garment that leaves one shoulder uncovered and an arm exposed. Gudea was zealous in granting the gods their due, and all his statues he commissioned showed his great piety, and wealth and pride. The statues are made of diorite an imported rare and dark stone that was very hard and difficult to carve. An inscription on the statue brags of the material it was made from as better than most materials. Almost two dozen portraits of Gudea survive. They were all based in temples. He built or rebuilt at great cost, the temples where his statues were placed. The headless example we have is important because it depicts Gudea with a temple plan on his lap. Building temples helped to insure blessing on the people and elevate Gudea’s pious position. Gudea’s portraits are in contrast to many works of rulers in that it emphasizes a more votive approach rather than emphasizing the ruler’s greatness in himself. Hammurabi The unification of Sumer under Ur was short lived and soon returned to the more familiar independent and coexisting city states for almost two centuries. Babylon asserted itself under the powerful rule of Hammurabi, reestablishing a centralized government over Southern Mesopotamia. Hammurabi (1792 -1750 BC) was famous for his conquests, but even more for his law code. The code is inscribed on a tall black-basalt stele that was carried off as booty to Suza in 1157 BC, together with the Naram -Sin stele. At the top is a relief depicting Hammurabi in the presence of the flame-shouldered sun god, Shamash. The king raises his hand in respect. The god bestows upon Hammurabi the authority to rule and enforce the laws. The sculptor depicted Shamash in the familiar convention of combined front and profile views, but with two important exceptions. His great headdress with its four pairs of horns is in true profile. Hammurabi’s code is among the oldest and the most extensively detailed written laws yet discovered. This is due to the discovery of the stele which depicts Hammurabi receiving the rod and ring, from Shamash, symbolizing authority. The symbols derive from builder’s tools--measuring rods and coiled rope--and connote the ruler’s ability to build social order and measure people’s lives and render judgments. The scene communicates that Hammurabi had the god-given authority to enforce the laws spelled out on the stele. Why is this important? Lion Gate (Hittite’s) The Babylonian Empire was eventually overrun by the Hittites, a people from Anatolia, who conquered and sacked Babylon around 1595 BC. They then returned to their homeland. The remains of their strongly fortified capital city are near Boghazkoy Turkey. In contrast to the mud brick of Mesopotamia, the walls were made of large blocks of heavy stone. Symbolically guarding the gateway to the citadel are two large seven foot lions. There are simply carved and project from massive stone blocks on either side of the entrance. This theme is echoed in other ancient cultures. The Palace of Sargon II at Dur Sharrukin (Khorsabad) During the first half of the first millennium the Assyrians were the dominant force in the Near East. Their name comes from the city of Assur, named for the god Assur and located on the Tigris River. At the height of power they ruled from the Tigris to the Nile and from the Persian Gulf to Asia Minor. The excavations of their palaces have yielded much. The unfinished royal citadel of Sargon II (721-705 BC) reveals in its ambitious layout, the confidence of the Assyrian kings and their might. Its strong city walls reflect a society fearful of attack during a period of almost constant warfare. The city is a square mile in area, with the palace on a mound 50 feet high and covering some 25 acres, with almost 200 courtyards and rooms. Sargon II regarded the palace as an expression of his grandeur. Lamassu Guarding the gate to Sargon II’s palace were colossal limestone monsters called Lamassu, winged man headed bulls placed to ward off the kings enemies. The task of moving and installing these massive creatures was so great it was depicted in limestone reliefs in the palace celebrating the feat. The Lamassu are giant high relief sculpture intended to be adjacent to corners and walls. They depict a conceptual view of the creature rather than an optical view. The frontal is at rest, whereas the side view depicts the creature in motion. In fact the creature is made with five legs to depict both views. (Two seen from the front and four from the sides, sharing on leg in each view) It is almost 14 feet tall. Relief Carvings Extensive narrative reliefs depicting battlefield victories and the slaying of wild animals decorated the walls. The degree of documentary detail in the Assyrian reliefs is without parallel in the ancient Near East. Nothing comparable has been found that was made before the Roman Empire. One of the most extensive and earliest examples of a cycle of narrative reliefs comes from the palace of Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC), at Kalhu. Throughout the palace, painted gypsum reliefs sheathed the lower parts of the mud-brick walls below brightly colored plaster. Rich textiles on the floor contributed to the luxurious ambiance. Every relief celebrated the king and bore an inscription naming Ashurnasirpal and describing his accomplishments. This example depicts an episode that occurred in 878 BC when Ashurnasirpal drove his enemy’s forces into the Euphrates River. In relief two Assyrian archers shoot arrows at a fleeing foe. The enemy soldiers are in the water, two apparently floating on inflated animal skins. Their destination is a fort where their compatriots await them. The fort is shown in the middle of the water. Why? It must have been on land some distance away. The artists purpose was to tell the story clearly and economically. In art, distances can be compressed and human actors enlarged so they stand out in their environment. Things are greatly out of proportion. The sculptor also combined different view points in the same frame, just as the figures are composites. Viewers see the river above while the figures and trees are from the side. Check out the archers do you notice something strange? The artist depicted the bow strings in front of their bodies but behind their heads. All these liberties with optical reality still result in a vivid easily legible retelling of a decisive moment in the king’s victorious campaign, which was the artist’s primary goal. Assyrian Painting Much rarer than stone reliefs, an example of Assyrian painting was glazed brick in which color was fused to the baked clay by firing. Our example depicts the king Ashurnasirpal II, with attendants and a soldier, as he is offering up a libation (ritual pouring of a liquid) in honor of the protective gods. Further Reliefs Reliefs were discovered in Ninevah, the palace of Ashurbanipal (668-627 BC), the conqueror of Elamite Suza. Made two centuries after the Kalhu reliefs, we see examples of hunting reliefs. This hunt was not in the wild but in a controlled environment to ensure the king’s safety and success. The lions were released from cages (not in this view) into a large arena. They charge the king in his chariot, who with attendants, fight off the beasts, leaving a trail of dead and dying animals repulsed using excessive amounts of force. The artist brilliantly expressed the staining muscles and veins of the beasts. Portraying the king’s adversaries with great strength, courage, and nobility served to further elevate the kings grandeur because of the worthiness of the foes. Babylon The Assyrian Empire was never very secure, often putting down revolts. During the reign of Ashurbanipal’s reign the empire collapsed from the simultaneous onslaught of the Medes and the Neo-Babylonians. The Neo-Babylonians controlled the Assyrian Empire until the Persian conquest. The most renowned Neo-Babylonian King was the great Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 BC) whose exploits are recounted in the book of Daniel in the Bible. Nebuchadnezzar restored Babylon to one of the greatest cities of antiquity. The cities famous Hanging Gardens were counted among the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. Its enormous Ziggurat was believed, by some, to be the ancient Tower of Babel. Babylon was built with mud-bricks, but faced with dazzling blue bricks faced the most important monuments. Ishtar Gate and Processional Way The Ishtar Gate was one of those impressive monuments. Each brick was glazed and the animal reliefs molded then glazed, separately, then set in proper sequence. On the gate profiles of Marduk’s dragon and Adad’s bull alternate. Lining the processional way leading up to the gate were reliefs of Ishtar’s sacred lion, glazed in yellow, brown, and red with a blue background. Persian Cyrus of Persia (559-529 BC) captured the city of Babylon. In 525 BC Egypt fell and by 480 BC the Persian Empire was the largest the world had yet known, from the Indus River in South Asia, to the Danube River in Northeastern Europe. Only successful Greek resistance prevented the Persians from embracing Southeastern Europe. The Empire ended with the death of Darius III in 330 BC, after his defeat to Alexander the Great. Persepolis The most important source of knowledge about Persian art and architecture is the ceremonial and administrative complex on the citadel of Persepolis. The city was built by the successors of Cyrus, Darius I (522-486 BC) and Xerxes (486-465 BC). It was built between 521 and 465 BC. Situated on a high plateau, the heavily fortified city stood on a wide platform overlooking the plain. Alexander the Great razed the site in a gesture symbolizing the destruction of Persian Royal power. Some said it was for the sack of the Athenian Acropolis in the early 5th century. Even in ruins the city is still impressive. The approach to the citadel led through a monumental gateway called the Gate of All Lands, a reference to the harmony among the peoples of the vast Persian Empire. Assyrian inspired colossal man-headed winged bulls flanked the great entrance. Broad ceremonial stairways provided access to the platform and the royal audience hall, or apadana, a huge hall 60 feet high and 217 feet square, containing 36 colossal columns. An audience of thousands could have stood within the hall. The reliefs decorating the walls of the terrace and staircases leading to the apadana represent processions of royal guards, Persian nobles, and dignitaries, and representatives from 23 subject nations bringing the king tribute. Every one of the emissaries wears his national costume and carries a typical regional gift for the conqueror. The reliefs are technically superb, with subtly modeled surfaces and crisply chiseled details. The reliefs like most ancient reliefs were painted, and must have been striking. The reliefs are more rounded and project further from the background, than those in Assyria. The drapery folds of the figures seem to be influenced by Greek Archaic art. Persian art testifies to the active exchange of ideas and artists among all the Mediterranean and Near Eastern civilizations to date. Under the single mindedness of the Persian masters, this heterogeneous work force workforce, with a widely varied cultural background, created a new and coherent style that perfectly suited the expression of Persian imperial ambitions. Sasanian Art Alexander the Great’s conquest of Persia in 330 BC marked the beginning of a long period of first Greek then Roman rule in large parts of the Near East, beginning with one of Alexander’s generals, Seleucus I (312-281 BC), founder of the Seleucid dynasty. In the third century AD, however, a new power arose in Persia that challenged the Romans and sought to force them out of Asia. The new rulers called themselves, Sasanians. The New Persian Empire was founded in 224 AD, when the first Sasanian king, Artaxerxes I (211-241 BC), defeated the Parthians. The Empire endured over 400 years, until the Arabs drove them out of Mesopotamia in 636, just four years after the death of Muhammad, the prophet and founder of Islam. The son and successor of Artaxerxes, Shaper I expanded Sasanian territory. He erected for himself a great palace at Ctesiphon, the capital his father had established near modern Baghdad in Iraq. The central feature of the palace was the monumental iwan, or brick audience hall, covered by a barrel vault (a deep arch over an oblong space) that came to a point almost 900 feet above the ground. The facade to the left and right of the iwan was divided into a series of blind arcades (a series of arches without actual openings, applied as wall decoration. A thousand years later, Islamic architects looked a Shapur’s palace and its soaring iwan and established it as the standard for judging their own engineering feats. Triumph of Shapur I over Valerian The Sasanian army was so powerful that in 260 AD, Shapur I succeeded in capturing the Roman Emperor Valerian near Edessa, (in modern Turkey). His victory over the mighty Roman Empire was so important that it was commemorated in a series of rock cut reliefs in the cliffs of Bishapur in Iran, far from the sight of triumph. Shapur appears larger than life, riding from the left and wearing the same distinctive tall Sasanian crown worn by the king in the silver portrait. The crown breaks through the relief’s border and draws attention to the king. The crumpled body of a Roman soldier lies between the legs of the king’s horse. This is a time honored motif. Here the sculptor probably meant to personify the whole Roman army. At the right, attendants lead in Valerian, who kneels before Shapur and begs for mercy. Above a putto-like or cupid-like figure, borrowed from the repertory of Greco Roman art hovers above the king and brings him a victory garland. Similar scenes of kneeling enemies before triumphant generals was common in Roman art, but here they are reversed, perhaps rubbing it in their face with their own compositional pattern. This adds an ironic level of political meaning to this message in stone. Conclusion The birth of civilization--urban life--and the invention of writing both occurred in Mesopotamia in the fourth millennium BC. There, the Sumerians built the first monumental temples and filled their religious precincts and tombs with statues, reliefs, and objects of gold, lapis lazuli, and other costly materials. Their successors - the Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Persians, and others continued the traditions of monumental art and architecture, erecting ruler portraits, stele recording victories and law codes, and great palaces decorated with painted narrative reliefs. At times challenging both the Greeks and Romans for supremacy of the Mediterranean, the empires of the ancient Near East finally succumbed to the Arabs in the seventh century AD. Thereafter, the greatest artists and architects of Mesopotamia worked in the service of Islam.