Gothic Conjugation

John Seery

Pomona College

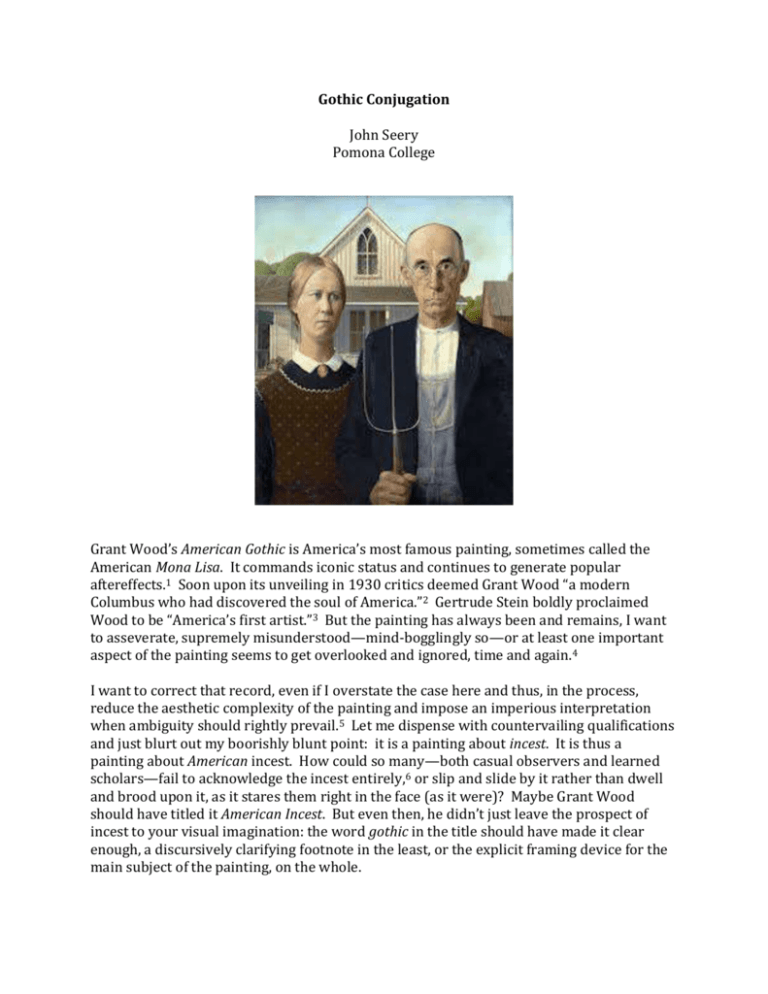

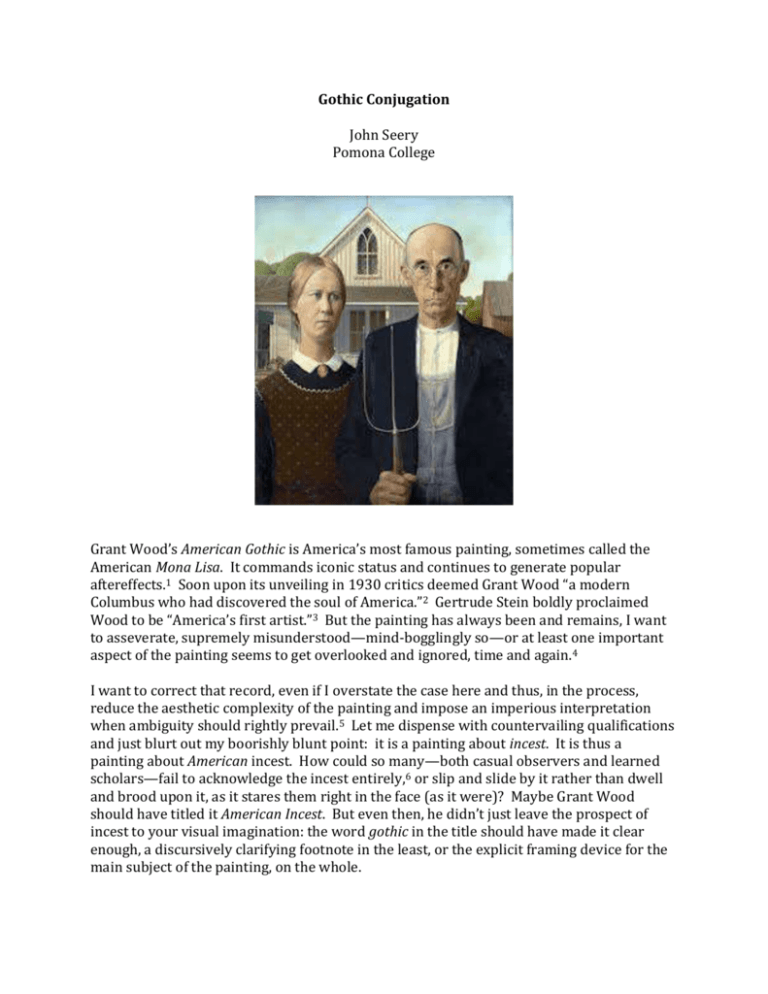

Grant Wood’s American Gothic is America’s most famous painting, sometimes called the

American Mona Lisa. It commands iconic status and continues to generate popular

aftereffects.1 Soon upon its unveiling in 1930 critics deemed Grant Wood “a modern

Columbus who had discovered the soul of America.”2 Gertrude Stein boldly proclaimed

Wood to be “America’s first artist.”3 But the painting has always been and remains, I want

to asseverate, supremely misunderstood—mind-bogglingly so—or at least one important

aspect of the painting seems to get overlooked and ignored, time and again.4

I want to correct that record, even if I overstate the case here and thus, in the process,

reduce the aesthetic complexity of the painting and impose an imperious interpretation

when ambiguity should rightly prevail.5 Let me dispense with countervailing qualifications

and just blurt out my boorishly blunt point: it is a painting about incest. It is thus a

painting about American incest. How could so many—both casual observers and learned

scholars—fail to acknowledge the incest entirely,6 or slip and slide by it rather than dwell

and brood upon it, as it stares them right in the face (as it were)? Maybe Grant Wood

should have titled it American Incest. But even then, he didn’t just leave the prospect of

incest to your visual imagination: the word gothic in the title should have made it clear

enough, a discursively clarifying footnote in the least, or the explicit framing device for the

main subject of the painting, on the whole.

2

The painting’s title tells us something about gothic horrors, but the painting doesn’t show

us those horrors outright. It obscures them, hides them, hints at them, presents them

obliquely, requires the viewer to figure things out. It is thus also a painting (to be insistent)

about cover-up, about guarded family secrets, about incest-as-taboo, family abuse as a

whispered practice largely left un-discussed, rarely mentioned let alone showcased in

public, but apparently prominent enough to be depicted as the backdrop to the American

family structure as such.7 If that’s Grant Wood’s insinuating assertion, why—after so much

lingering scrutiny of this painting, 85 years worth—haven’t we been talking about it?

In analyzing American literature, literary scholars routinely associate the genre and history

of gothic novels with incest;8 in fact, gothic incest tropes are so commonplace in the U.S.

literary canon and, accordingly, so commonplace in the secondary literature, they are now

regarded as cliché and a bit passé, a shopworn scandal.9 But art historians and museum

curators who write about Grant Wood seem to have a hard time connecting the dots

between incest and the gothnic-ness of American Gothic. The few who do dare mention it,

quickly and tight-lippedly drop it.10

Surveying the scholarship about American Gothic, one notices a common form of

storytelling: commentators typically indulge in retellings of Wood’s upbringing and

biography and then use these vaguely contextualizing anecdotes to forward a particular

interpretation of American Gothic, one with a warmly homespun spin. The basic story goes:

Grant Wood was born on a farm in Iowa; when he was ten, his father died; the family

moved to Cedar Rapids; after high school the budding artist left Iowa for Minnesota; then

he left the U.S. for Europe to study the art masters; then he broke from European influences,

returned to his native land, transformed his style of art and became the regionalist painter

about whom one now reads in art history textbooks, a rather good-natured, salt-of-theearth fellow whose folksy signature was to paint haystacks that look like gumdrops and

trees that look like lollypops.

One day, the story goes, the ever do-gooding Grant Wood stumbled upon a modest

farmhouse in Eldon, Iowa that was a quaint example of the “carpenter gothic” style of

country home building. He had studied Gothic cathedrals in Europe, so something about

the transplanting of high-European religiosity onto the lowly plains of the Midwest called

out to him for visual rendering. He made some sketches, he asked a woman and a man to

pose as models for him, and he painted a farm couple standing in front of the house. He

entered the painting in a contest, it won third place, the Chicago Institute of Art purchased

the painting, some people thought he was making fun of farmers, but almost immediately

the painting became famous and Wood became an overnight celebrity. Snooty East-coast

art critics, academic and otherwise, enjoyed the apparent dig at Midwestern provincialism

but didn’t regard the painting as worthy of sustained scrutiny, although crafty advertisers

and clever cartoonists kept the image alive in the public domain through parodic recastings

of the couple.11 From 1930 to 1990 or so, a viewing consensus (more or less) emerged

about the painting, a stabilized interpretation to the effect that homey, wholesome, cornpoke-ish Grant Wood had produced a regionalist gag piece whose pious characters may be

stern, perhaps troubled, okay maybe slightly creepy, but certainly not downright diabolical.

Surely good-natured Grant would do no such thing.

3

And so, cherubic homeboy Grant Wood is commonly construed and rendered to be

characterologically incapable of painting a painting about incest. Such selective biography

mapped onto regionalist stereotypes apparently provide sufficient solace and safeguard

against the threat of caustic national critique. An upright reading of American familydom,

one that requires moral and visual blinders, then prevails and suppresses the painting’s

possible depravities.

A few art historians started breaking ranks with the one-sidedly reverential reading of

American Gothic. In 1974 Matthew Baigell called the painting “a vicious satire.”12 In 1975

James Dennis detected sinister, Edgar Allen Poe-like forces at work in the painting.13 In

1983 Wanda Corn broke the story that the couple was never meant to be a husband and

wife but, instead, was a painting of a protective father and his unmarried daughter.14 Corn

attended carefully to the conflicting connotations of the term gothic in the title, and she

inquired into the possibility that a gothic painting about a father and his spinster daughter

might well spell trouble out on the isolated plains of mid-America—and Wood had indeed

been hanging out with local writers who wrote about farmers’ spinster daughters as a

source of sexual trouble—but Corn resolved her doubts in favor of an affectionate rather

than vexed reading of the painter’s intent and, therewith, of the painting’s import.15

And then a second wave of American Gothic trouble hit: hometown hero Grant Wood was

gay! Who knew? In 1997 Robert Hughes outed Wood as a “deeply closeted homosexual”

and called American Gothic the expression of a “gay sensibility.”16 In 1998 I had a few

words to say about Robert Hughes’ “gay camp” analysis,17 and in 2000 Henry Adams also

discussed Grant Wood’s person and paintings as gay.18 By 2010 R. Tripp Evans had

produced a massive tome dedicated to exploring the total gayness of Wood’s oeuvre,19 and

in 2013 James Maroney, Jr. regretted that Evans had beaten him to the gay punch.20

But the traditional and the troubled interpretations have not been squared off against, let

alone reconciled with, one another. How, one now wonders, could a single twodimensional painting provoke and sustain these archly rival readings: the straight reading,

the incest reading, and the gay reading?

Maybe every painting is subject to interpretive projection. If Harvard historian Steven Biel

is right, American Gothic especially lends itself to multiple interpretations; and scholarly

commentators of the work, if Biel is right, should acknowledge those plural and rival

readings of the painting but, if they are to follow Biel’s own example, they shouldn’t try to

adjudicate and judge between and among them. Biel seems to be playing the role, too well,

of an impartial historian who stands above the interpretive fray (which means, you manage

to write an entire book about American Gothic and yet mention incest but once, and barely

so). Corn seems overly intent on making Grant Wood a respectable figure for the stodgy

world of art history, which for years had excluded American Gothic from high-minded

acceptance. Evans’ mission, focusing on Wood-the-artist as gay, is overwhelmingly clear

(although Evans’ gay-gloss doesn’t sit well, on his telling, with any strong emphasis on

incest; instead, Evans construes American Gothic as Wood’s confrontation with his manly

father). Thomas Hoving, former director of the Metropolitan Museum in New York,

4

explicitly wants to redeem an art connoisseur’s non-scholarly, directly observational

approach to American Gothic, and so he thinks it best to notice, for instance, the painting’s

blue sky rather than “getting hung up” on the gothic window.21

My own agenda isn’t to push in order to privilege, finally, a definitive interpretation over

others’ insights into the painting. Rather, my sharp-elbowed concern is that so many

viewers of the painting, scholarly and popular, seem to be engaging in incest-elision and

incest-avoidance as they struggle to discern and to narrate the significance of the painting.

In the spirit of full disclosure, allow me to digress for a bit, in order to reveal my own stakes

and investments (as I see them) in the painting. This “here’s where I’m coming from”

background is precisely about where I came from, namely Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Wood’s

hometown was also the city of my birth and youth, though we belonged to vastly different

eras (66 year age difference, with no overlap). I calculate that my father’s parents’ farm, in

Coggon, Iowa, was about 15 miles from Grant Wood’s parents’ farm, 4 miles east of

Anamosa. Like Wood, I attended Cedar Rapids Washington High School (different buildings,

though). In retrospect, I realize I walked in many of his tracks: the Carnegie public library

where I cut my teeth was the place where he exhibited his early paintings; he taught some

classes at Coe College, and I spent a good deal of time on that campus, and one of my sisters

was graduated from there; for my lumberyard summer job every summer, for which I had

to travel from the N.E. side of town to the S.W. side, I passed right by, literally hundreds of

times (via 2nd Avenue, for the natives), Wood’s studio at 5 Turner Alley, where he painted

American Gothic.

But I must say: as a kid growing up in Cedar Rapids, I never thought about Grant Wood.

Looking back, I don’t think it occurred to me even once that I was passing Wood’s studio

during all the times I drove past it—that just didn’t matter. We never discussed Grant

Wood in the schools, though I guess we were aware on some level that he had been an

artist who achieved some acclaim—somewhere. During my years in Cedar Rapids, I never

once visited the Veterans Memorial Building, which houses Wood’s gothic War Memorial

stained glass—that building was a place you entered only if you wanted to watch

professional (i.e., fake) wrestling matches. Yes, I was aware that there was a Grant Wood

Elementary School in the city, but that was of note only because a friend’s father had been

the architect of the building, which he designed as two white-roofed cone-shaped buildings

connected by a walkway—and so everyone joked that the school looked like a woman’s

brassiere.

Though Cedar Rapids had plenty of civic boosterism in those days, no one tried to impress

the up-and-coming youth that bygone locals-made-good, such as Carl Van Vechten, Bobby

Driscoll, William Shier, Paul Engle, Arthur A. Collins, and Grant Wood, should serve as role

models for the rest of us. We weren’t taught to identify with them, and we didn’t care about

them. I didn’t give a hoot about Grant Wood.

Flash forward to my mid-thirties: by then a Ph.D’ed political theorist who had taught at

several universities, I was fortunate to spend a sabbatical year at the Stanford Humanities

Center, during a time when Wanda Corn served as Director of the Center. Early on that

5

year, Wanda gave a brilliant and eye-opening presentation on Grant Wood and American

Gothic. She started her talk not by lecturing, but by asking us—the fellows in residence—

to look at the painting and tell her what we saw. I knew enough about that painting to

know that she was stepping on my hometown turf, but I didn’t feel at all proprietary (more

like plain old stupid, especially regarding art history). My initial, untutored reaction was

that the man in the painting bore a distinct resemblance to my grandfather: bald-headed,

gaunt-faced, wire-rimmed glasses—and a farmer. Wanda pointed out some of the

painting’s features that we, as a group, had overlooked: the pitchfork echoed in the man’s

overalls; the serpentine strand of hair falling out of the woman’s hair bun; the pitchfork as

mirroring, upside-down, the gothic window above. She then told the tale that the woman

who posed for the painting was Wood’s sister, Nan, who was 30 at the time; and the man

who posed, Wood’s dentist, was 62 at the time. The age disparity between the two, on

closer inspection, perhaps becomes noticeable enough, while also remaining open to

question. And so Wanda dropped the bombshell that this couple was a father-daughter

couple, not a husband-wife pairing—though the ambiguity might provide some salacious

colorings. But Wanda assured us that amiable Grant Wood was just not that kind of guy.

Something at the time struck me as wrong. By then, I had published a couple of books on

irony, and during that year in residence at Stanford I was writing a book about death; the

bridge between the two, irony and death, had to do with my being obsessed with the

Orphic tradition of infernal travelers, dead poets who commune across generations via

ironic artistries. So my head was primed at the time to receive Grant Wood as a

mischievous Orphic artist. But closer to home, my own experience spending time on family

farms (my mother also grew up on a farm, in Ossian, Iowa) quickly divested me of

romanticizing farm life. Whenever (still) I hear others speaking in a romantic register

about family farming, I suspect that they don’t quite know what they are talking about. To

me, the farm—whatever its virtues—was also a place of blood, animal dung, dirt, bad

smells, violence, killing, patriarchy, isolation, abuse, and addiction, both wet (alcoholism)

and dry (religion).

6

By all accounts, Grant Wood hated his early years on the farm—at least the farming part—

and sympathetic commentators tend to read his later “regionalism” as a homecoming

reconciliation with his past (those gumdrop haystacks and lollypop trees of his are so

fanciful!). My farm-animus-detector, however, sensed that Wood’s fabled landscapes—the

basis for his renowned “regionalism”—were perhaps an ironic cover for the complicated

views of a 1st generation citified individual. With respect to American Gothic’s threat of

father-daughter incest, Corn seemed to me to soften that menace by claiming that Jay

Sigmund and Ruth Suckow—Wood’s close friends who were publishing darkly sexualized

works around the farmer’s-spinster-daughter theme—were deploying that farmer’s

maiden daughter merely as a “stock literary figure.”22 Me, I suspected that such a figure

might be more than just a literary contrivance.

Some facts and figures I am now adducing, though I already knew them experientially,

growing up in such an environment: The sociological and demographic history of Iowa in

the 19th and 20th centuries featured a landscape dotted by a multitude of ethnic-religious

communities, bounded communities that were bumping up against one another and were

thus struggling to retain their respective self-same identities. Next to Cedar Rapids was the

Amana Colonies, home to a German-Lutheran pietist group. Cedar Rapids had also been

home to a sizeable Czech community, an African-American community, as well as an ArabMuslim community. Pella, Iowa had attracted a large group of Dutch Reformer immigrants.

Kalona (and elsewhere) was home to a good number of Amish and Mennonite groups. The

Mesquaki Native American tribe had its reservation in Tama, Iowa. Other outposts

featured French Icarians, German Swedenborgians, Mormon sects, Swedish Baptists,

Swedish Methodists, and dedicated Jewish enclaves. Throughout Iowa there were selfstanding (and often long-standing) immigrant communities from Hungary, England, Wales,

Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Scotland, Ireland, Switzerland, Austria, Russia, Italy, Canada,

and Croatia.23 Such groups erected formidable barriers against assimilation into any

supposedly stewing Midwestern melting pot.

My mother, Mildred Jean Knudsvig, hailed from nine generations of “purebred” NorwegianAmerican Lutherans. My father, Francis Thomas Seery, hailed from five generations of

purebred Irish-American Catholics. The two left their isolating farm-religico communities

and met and mingled in Cedar Rapids. Big band jazz brought them together, as well,

perhaps, as did the increasingly scientific and agricultural atmosphere of corn hybridity

that one found promoted and sold in the city. Suffice to say, my parents’ respective clans

were not happy by Mildred’s and Francis’s defecting (even sacrilegious) experiment in

exogamy.

In such a setting, the ethnic and religious pressures for procreation, and in particular, inbreeding of some kind, were palpable, fierce, and consequential. Grant Wood came from a

sternly devout Quaker farm family (his father forbade the reading of fairy tales). In Cedar

Rapids, Wood knew he was the subject of a good deal of whispered town gossip about why

he wasn’t yet married. He heard the swirling rumors about how he was too close to his

mother. His sister was encroaching on spinsterdom when she married at 24 (and was

separated from her husband at the time she posed for American Gothic). Wood reportedly

wanted to find a genuine spinster to pose for the painting, but was too embarrassed to put

7

that question to anyone, so he settled for his sister (a faux-spinster but a credible stand-in).

At the time he painted American Gothic, his mother and his sister were living with him in

the 900 square foot apartment at 5 Turner Alley. The three were sleeping side by side by

side (his sister in the middle), like sardines in a can. Small wonder, perhaps, that Sigmund’s

and Suckow’s fascination with sexual and gender turmoil in middle-American families

might seem more than merely literary to Grant Wood in such rumor-filled, supercharged

settings, within his studio apartment and throughout the region at large.

What, if pressed, would be the basics for an incestuous reading of American Gothic? I don’t

have a formulaic methodology in mind; more like a mish-mash argument drawing on

formal elements in the painting along with extramural evidence. Such a case will remain,

after all, circumstantial and speculative. There can be no smoking gun for naysayers (that

is, if the title doesn’t count as one). I suppose I, too, am importing my own gut sense of

Grant Wood’s person into the presentation, a homegrown sense of him as capable of

sustaining wry irony, someone who partially conceals his motives and meanings (maybe

even to himself). Exhibit A: His public comments about American Gothic were always cagey

and provocative, never serving to quell controversy; for instance, about American Gothic he

said, “I’d rather have people rant and rave against my painting than pass it up with ‘Isn’t

that a pretty picture?’”24 And he conceded (an “admission”) that the painting projects an

apparent contradiction about the figures portrayed, between falseness and goodness: “I

admit the fanaticism and false taste of the characters in American Gothic, but to me, they

are basically good and solid people.”25 (Wanda Corn and R. Tripp Evans both seize on this

quote, at length, to emphasize the “basically good and solid people” side of Wood’s

testimony;26 but I wonder about Wood’s peculiar use of the term fanatic: in what sense are

these people “fanatics?” Because they worked hard? Because they were die-hard religious

believers? Because they had doggedly pursued an American dream? Something’s missing.)

I find additional support for Wood’s devious inscrutability in a comment his friend Paul

Engle made in a 1977 interview (cited by Evans): “Sudden success also brought almost

instant sadness and darkness to Grant, [but] that is another story. He was a gifted, fine,

complicated person…[whose] outward, cheerful, plain-person image concealed a troubled

life.”27 Evans reads that concealed trouble as closeted homosexuality; I would not disagree,

but I don’t think that that word, that concept, that analytic angle—homosexuality—conveys

the whole story.

I want to say that the painting discloses all sorts of possible lines and legacies of incest:

father-daughter; daughter-father; mother-son; sibling-sibling; father-son; Biblical; ancient

Greek; Roman; Christian; middle-European; American; and maybe more.28 The canvas is a

palimpsest of past and poorly understood transgressions; it is, as Freudians might say, an

overdetermined, frozen-frame snapshot that has multiple, moving, and murky influences

leading up to it.

The painting’s overcast ecclesiasticality draws on a number of visual cues: the painting is a

formal exercise in verticality (Grant Wood even said as much); the figures are elongated;

our eye looks upward; we notice a possible church spire in the background; the gothic

window is echoed in the woman’s hair-do as well as the pitchfork; the pitchfork is repeated

8

in the man’s overalls; the man is wearing a black overcoat that could be associated with

Sunday service. The woman’s face is a knock-off Madonna-face from the Renaissance

period29 (as well as a knock-off Victorian face30).

But the pitchfork is also a sharp, violent instrument, the signal tool of the Devil, so the

straightforwardly church-ish reading starts to go south. The blackness of the man’s

overcoat, for instance, now looks a bit worrisome. We start to suspect gender trouble in

the couple’s body language. The woman’s averted gaze, on close review, looks disconcerted

and disconcerting—more than just the look of preoccupation. The man’s eyes, slightly offkilter we now observe,31 do not engage us directly and thus, also slowly unsettle. On

second thought, both sets of eyes could be the eyes of a victim or a perpetrator.

The strand of hair falling out of the woman’s hair bun is clearly serpentine. We notice (or

learn, after Googling) that one of the plants on the porch is a “snake plant” (sansevieria

trifasciata). The woman’s cameo brooch seems to feature a fuzzy allegorical figure with

possibly snaky hair. What’s up with all the snakes on the woman’s side of the painting in

American Gothic?

Wood-ites will quickly explain at this point that just prior to painting American Gothic,

Grant painted a painting of a woman holding a snake plant, titled Woman with Plants

(which, in addition to a sansevieria features a begonia, which is also carried over into

American Gothic; also carried over is the same cameo brooch). An elderly Madonna figure

holding a snake plant (in Woman with Plants) would seem to skew pretty conspicuously

toward a biblical interpretation, a mash-up of Edenic and Christian themes. The basic idea

of situating a woman with a snake in a garden environment: we’re now in the realm of

originary temptation and forbidden knowledge. Then take note of the odd fact that the

model for Woman with Plants was Grant’s mother: we probably—eventually—have to ask,

what does it mean to depict a withered woman as a snaky, Eve-like temptress? And more,

what does it mean to depict your elderly mother as a biblical temptress, the basis for the fall

from innocence? And then, jumping back to American Gothic: if we see sexual temptation

thematized in Woman with Plants, is it too far a stretch to extend that Genesis story

(recontextualized to a midwestern farm setting) to Lot and his daughters in American

9

Gothic? The Lot story is not about a father abusing his daughters; rather, it is about

daughters taking sexual advantage of their drunken father (for the sake of procreation, and

maybe more). We start to recall that Jay Sigmund described the farmer’s spinster daughter

as a sexual monster with cruel fangs.32 And Ruth Suckow wrote several sad pieces about

the frustrations (including sexual) of isolated farmwomen. Maybe their good friend Grant

Wood wasn’t exactly a naïf about such matters.

Looking over American Gothic again, one’s eye might be drawn to that fateful gothic

window, and then it might occur to one to ask: What goes on behind the closed curtains of

that gothic window, which formally ties together the man and the woman in the painting?

If the woman is a daughter, where’s the man’s wife? If the daughter is standing in for the

wife at the moment portrayed in the picture, does she stand in for the wife upstairs in the

bedroom of the gothic house as well? (Literary theorists immediately understand houses in

the American gothic tradition as a site of domestic abjection.33) Maybe the daughter has

tempted the father. Maybe the father has violently abused his daughter. Maybe, if the

cameo brooch depicts a snake-haired Medusa, a mythic figure whose gaze turns men into

stones, we are looking at a woman whose gaze has turned the man in the painting into a

man of stone (and, by extension, if we mesmerized spectators stare at the painting in a

certain way, perhaps we are liable to become emotionally blinded to his horrors?34)

In another interpretive stretch—but maybe not, given Wood’s mythic, biblical, allegorical,

and literary chops—we recall that Oedipus blinded himself with his mother’s brooch. The

brooch that appears in Woman with Plants and American Gothic was, in real-life, a brooch

that Wood bought in Italy for his mother. On that stretched reading, Wood, in painting

Woman with Plants and American Gothic as companion pieces, would be depicting

himself—a painter concerned with motifs of visibility and invisibility—as Oedipus,

someone who has slept with his mother and who has, unwittingly, killed his father. Are we

overthinking the brooch (and its allusive connections to snakes), or did Wood deliberately

(or sub-consciously) make it a visual centerpiece, in two companion pieces, for us to behold

and to ponder beyond its surface appearance?

Thinking about the continuities and transitions from Woman with Plants to American

Gothic: if Wood substituted his mother-model in the former for his sister-model in the

latter, can we psychoanalytically translate the obvious mother-son incest of the former to

brother-sister incest in the latter, thus recognizing sibling incest as the background drama

for American Gothic? (A Madonna motif can bespeak either motherhood or virgin-girl-dom,

or both at once). Or are we just taking this too far?

Some recycled hearsay to add to the mix: Growing up, Grant was something of a momma’s

boy on the farm, cowering under his mother’s influence, and literally under her apron, out

of fear of his overbearing father.35 Later, as an adult, Grant referred to his mother as “the

most beautiful woman in the world.”36 He told people that he would never marry anyone

while his mother was still alive, and several writers mistakenly referred to Wood and his

mother as a married couple (Wood’s secretary even wrote a play in which he slipped up at

one point and referred to Wood’s mother as “Mrs. Grant”37). At 34 years old, as a man who

had never dated, about whom gossipers wondered whether he loved his mother “too

10

much,” he asked his mother to move in with him, into his dinky studio apartment at 5

Turner Alley. His mother would explain that she moved in “solely to please Grant.”38 For

ten years they slept side by side (albeit in separate pullout beds), and the reported plan to

provide her with a separate, cordoned off bedroom space in the studio never materialized.

When he finally married (after his mother’s death), Grant married a woman who was close

to his mother’s age, a woman who had looked after Wood’s mother when she was ill; and

even during that short-lived marriage, Wood’s travel companion and publicist, Park Rinard,

lived with the couple. As for his relationship with his sister Nan, one of Nan’s friends would

later say that Grant was “everything to her—a father, brother, and friend.”39 When Nan did

marry for a spell, she noticed that “seeing our [her and her husband’s] love was hard on

Grant.”40

American Gothic—so titled—makes an audacious claim of some sort, a claim on and about

us, as Americans, such that a gothic aspect or underbelly is to be ascribed to our national

character. It behooves us to take up the interpretive challenge the artist seems to lay out

before us. How are we to make sense of the two senses of the gothic? How are we to bring

together the clash of the traditional and of the troubled (gay and incest) readings? Allow

me to draw on some theoretical frameworks by which we might be able to piece together

some parts of the puzzle.

A Freudian reading:41 The standard Freudian formula (which may not be a good reading of

Freud after all42) is that an incest taboo helps liberate children from the throes of their

overweening parents; it helps children grow up, and sends them out into the world. By that

account, Grant Wood would seem to have been locked in an arrested, pre-sexual state of

development wherein he successfully claimed ongoing possession of both his mother’s and

his sister’s full affections. In the process, he experienced no great Oedipal tussle,

triangulation, or resolution with his father, who died before the male-to-male contest ever

escalated. Such a reading would perhaps help explain the sardine-like bedroom

arrangements at 5 Turner Alley as well as the apparent fungibility (and ambiguity) of

mother-daughter (and barren/virgin) images depicted within and across Woman with

Plants and American Gothic.43 But (to shorten a more elaborate critique) a Freudian

apparatus isn’t very helpful at getting at gay desire, relegating it instead to stunted or

aberrant sexual development; and it doesn’t lend much positive insight into non-Oedipal

personalities. It does alert us to incest, but the prospect of homosexuality throws it for a

loop. Judith Butler’s critique of Freudian analysis is apt here: Freud’s emphasis on Oedipal

incest needs to be exposed as a heteronormative conceit, a thoroughgoing bias or

unexplored assumption that heterosexual desire is the norm and anything else is immature

or aberrant.44 Butler, like Robert Hughes before her, would thus help us see American

Gothic as a possible spoof on heteronormative coupledom; but even with her helpful

critique of Freud, it’s still hard to understand why a gay painter would, in Woman with

Plants, depict his elderly mother as a wrinkled temptress.

A gay reading: Evans uncovers extraordinary evidence about Wood’s obsession with his

mother, and he drops the word incest several times in his analysis but then swiftly backs

away and repairs to a conclusion that Wood’s mother-love—in life and apparently in

painting— provided a “platonic” shield and alibi for being gay. Curiously Evans doesn’t

11

deploy any sort of Edenic rendering of snakes in parsing Woman with Plants and American

Gothic, a conspicuous omission which certainly eclipses any connotation of mother-astemptress or spinster-as-temptress. He interprets the snake plant in Woman with Plants as

a symbol of “phallic aggressiveness,”45 and the plants in the painting “identify Hattie

[Wood’s mother] with the goddess of domesticated plants as surely as the harvest scene

behind her”—namely, the classical figure of Demeter.46 He finds the strongest evidence for

this Greek-ified reading of the painting—again, with Hattie as Demeter—in the brooch

she’s wearing. He claims that the original brooch clearly features pomegranates in the

figure’s hair, which he says clinches his Demeter reading—though he wonders why Wood

painted the figure in the cameo in an “illegible” manner.47 His answer is that Wood wanted

to keep private his association of his mother with Demeter, a mother in mourning—yet

Evans proposes nevertheless that a Demeter theme somehow promotes in the painting a

seasonal, pastoral connection to death and rebirth, which somehow accords with Wood’s

own homecoming to Iowa.

Pushing that undercover interpretation even further, Evans speculates that Wood’s first

choice of the woman model for American Gothic “was, in all likelihood, his mother.”48 He

imagines that the couple was originally supposed to be a depiction of Wood’s own mother

and father (question: how, exactly, would that be “gothic?”), but Wood, Evans reasons,

refrained from asking his mother because it would have brought painful memories back to

her. Choosing his sister Nan instead, Wood defused the unsettling image of his parents’

reunion. But (and Evans’s interpretation seems to depend on a whole series of such

imagined steps) that new pairing provided an opportunity to present his sister as a

Persephone figure in the company of her underworld abductor, Satan.49 The loosened hair

from the bun depicts, says Evans, the violence of Persephone’s kidnapping, and at the same

time suggests the loss of sexual inhibition in Persephone’s physical union with Hades. The

snaky hair might also, he ventures, connect Hattie to Medusa (thus making the brooch not

so definitively a Demeter brooch after all)—and all of that virginal sexuality, Evans admits,

might raise issues about “the darkened bedroom window Wood positions between these

two figures”—but he concludes that such hints of sexuality between the maiden and the

man merely draw a “connection to jokes about promiscuous farmers’ daughters.”50 In the

end, Evans thinks that the farm couple in American Gothic—effectively Wood’s mother and

father—wasn’t a critical portrayal at all, because “Wood respected his parents too much,

and loved them too deeply, to have attacked them in this work.”51 Unlike a possible Judith

Butler reading of American Gothic as a spoof on heteronormativity, Evans essentially views

the painting as a gay man’s covert (and uneasy) exercise in heteronormative restoration

and father-son reconciliation.

Evans’s wildest conjecture is that “Wood appears to have longed, at some level, to be his

sister and assume her privileges within the family.”52 That’s basically the extent of Evans’s

“gay” reading: kindly Wood wanted to be effeminate and yet yearned belatedly for the

approval of his manly father. Such a reading requires that Evans contain any incest

contamination between Wood and his mother, between Wood and his sister, and between

Wood and his father.53 It requires a bucolic reading that relies almost entirely on Greek

rather than Genesis myths.54 It’s a reading that seems premised on the unspoken

12

assumption that a closeted gay man, such as Grant Wood, could never truly be a painter of

the gothic—which contravenes almost everything we know about the gothic genre.55

A queer (as opposed to gay) reading: Michel Foucault famously made the claim that

homosexuality was not “invented” until around 1870. Following Foucault, I suggest that it

might be inapt or awkward or reductive to deploy retrospectively the contemporary

analysis of gayness (or homosexuality) in order to understand Grant Wood’s 1930ish

milieu. Wood, I submit, simply doesn’t fit well into a “gay” box. Also following Foucault,

numerous writers—especially those concerned with the gothic—will often use, instead, the

more protean term queer in order to get at subversive sexualities that elude or exceed

latter-day sexual binaries. Foucault also makes the point that the modern family is not

simply a private realm unto itself but is, rather, the locus of an extensive regulatory

apparatus that connects sexuality and kinship with economic and political structures of

power.56 To cut to the quick: Foucault (like Freud, but divested of ambient homophobia)

thinks that family incest is the unspoken secret lurking behind and propping up our

economic and political institutions. Interrogating family incest, then, is a good starting

point for conceptualizing radical social critique.

Ruth Perry, following Foucault’s lead, points out that many of the gothic/incest writers of

the late 18th century were women and gay men. Why, she asks, did the gothic tropes of

incest so appeal to homosexual men in particular?57 By way of an answer she cites several

authors who propose that the conventions of gothic/incestuous desire provided a

protective camouflage, a screen, for an even-more forbidden desire, namely homosexual

desire.

Agnieszka Monnet, also explicitly following Foucault, goes beyond a “gay screen” analysis

and places Grant Wood’s American Gothic in a gothic tradition of “queer” critique.58 Gothic

queerness, she proposes, isn’t simply an aesthetic depiction of transgression; it also

prompts or induces (or “performs”) self-implicating ethical and political skepticism. We

look at American Gothic and we sense scandal; but the ambiguous form of storytelling

doubles back upon itself and invites us to question why we define the wrongdoing as

wrong in the first place.59 That might be the real horror of the gothic: it doesn’t simply

bring to light and expose scandal; it also calls into question, as inadequate, our

conventional categories of moral and political judgment.

For Monnet, the gothic queerness of American Gothic —its ambiguous portrayal of incest

both as taboo and as family norm—gestures in the direction of radical questioning and

limns the possibility of a radical politics of some sort. To use her terminology, American

Gothic ought to be regarded as a “protest painting.”60 For Monnet, incest isn’t just a cover

for homoerotic desire; rather, incest is a kindred (rather than competing) trope for

prohibited self-sameness. Grant Wood, by making the woman figure in American Gothic

scandalously ambiguous, seems to be calling into question the very roles of mother,

daughter, wife, father, the family in general, and the larger national arrangements

(“American”) for constituting family life. From that widened perspective, the traditional

and the troubled readings of the painting no longer seem so opposed; the incestuous (and

13

queer) family narrative starts to occupy the same standing as the iconic American family;

the two senses of the gothic start to blur into one.

Recall that Wood explicitly said that he didn’t want people to gawk at American Gothic and

conclude merely that it is “a pretty painting.” The painting doesn’t seem, on that authorial

testimony, to be an inducement finally toward consolation and reconciliation; it serves,

rather, as a lingering provocation (a protest painting, one that incites people to “rant and

rave,” as Wood expressly preferred). For what alternative politics, you might ask? The

philosopher Richard Rorty condemned the gothic mode as a “stumbling block to effective

political organization,”61 whereas democratic theorist Bonnie Honig responds that gothic

ambivalence may help rouse receptivity to pluralized and de-romanticized political

attachments and projects.62 Perhaps the queer provocations in American Gothic don’t

readily translate into an “effective political organization,” but we likely could heed them as

a cry for alternative notions of family and of love: Maybe living with your elderly mother in

close confines isn’t an exercise in arrested development, aberrant sexuality, Platonic

shielding, or gay cover-up. Maybe Grant Wood’s queering the American family, resisting (in

real life) and depicting (on canvas) our conventional arrangements as constrictive and

abusive, is coaxing us in roundabout ways toward more capacious loves and everlasting

commitments. Maybe the subversive sense of the gothic in American Gothic doesn’t

sabotage entirely the iconic overtones of the gothic in the painting: maybe the painting is

both affirmation and protest, such that it makes sense for Wood to insist, after all, that his

Gothicized subjects, despite all of their faults, are “basically good and solid people.” As

Bonnie Honig says, in gothics, “the nice guy and the scary one are often the same person.”63

For me, the marvel of American Gothic is that it does seem to invite and sustain multiple

and rival interpretations.64 Viewers are certainly entitled to look at the painting and see

what they see (or not see). My incest reading, a corrective account, isn’t meant to erase a

“Greek” or “gay” or even a straightforwardly straight interpretation of the painting. I

welcome and appreciate the many rich readings the painting continues to generate. I do

insist, however, that the non-incest readings of the painting cannot make full sense of the

painting’s title.

See especially Wanda M. Corn, Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision (New Haven: Yale

University Press, 1983); Steven Biel, American Gothic: A Lie of America’s Most Famous

Painting (New York and London: Norton, 2005); and a plethora of websites devoted to

American Gothic parodies.

2 Ernest Goldstein, Grant Wood, American Gothic (Champaign, Illinois, Garrard Publishing,

1984), p. 2.

1

14

Henry Adams, “The Real Grant Wood,” Art & Antiques:

http://www.artandantiquesmag.com/2010/10/the-real-grant-wood/

4 A few examples in which the threat of incest seems to have been overlooked: J. Seward

Johnson, Jr. produced a 25-foot-tall statue of American Gothic that was exhibited in Chicago

and has been traveling through the country, titled “God Bless America.” Michael Daugherty

(Cedar Rapids native) composed an “American Gothic for Orchestra” piece (2013) that

features a bluegrass hoedown. A good number of children’s art books have appeared in

print, designed to introduce kids to American Gothic. In 2008 filmmaker Sasha Waters

Freyer produced a wonderful film, “This American Gothic,” which, incidentally, features

Wanda Corn, Steven Biel, and myself as talking-head commentators; my own comments

about incest, however, didn’t quite make the final cut.

5 I am well aware of the impossibility of policing the meaning of art works: see Jacques

Derrida, “Restitutions,” in The Truth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod

(Chicago: University of Chicago Pres, 1987), pp. 255-382.

6 Several big, glossy Grant Wood books written in the last 20 years don’t mention incest at

all; to name just a few: Kate Jennings, Grant Wood (Avenel, New Jersey: Crescent Books,

1994), Brady M. Roberts, James M. Dennis, James S. Norns, and Helen Mar Parkin, Grant

Wood: An American Master Revealed (San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks, 1995); Wende

Elliott and William Balthazar Rose, Grant Wood’s Iowa (Woodstock, Vermont: The

Countryman Press, 2013).

7 Grant Wood said, shortly after the unveiling of American Gothic, “The people in American

Gothic …are American…and it is unfair to localize them to Iowa.” “Open Forum,” Des Moines

Sunday Register, December 21, 1930. AAA, 1216/286.

8 Ruth Perry, “Incest as the Meaning of the Gothic Novel,” The Eighteenth Century, vol. 39,

no. 3 (1998), pp. 261-278; Shawn Salvant, “Pauline Hopkins and the End of Incest, “ African

American Review, vol. 42, no. 3-4 (Fall-Winter, 2008), pp. 659-677; Bernice M. Murphy, The

Rural Gothic in American Popular Culture: Backwoods Horror and Terror in the Wilderness

(New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013); Mary Chapman, “The Masochistic Pleasure of the

Gothic: Paternal Incest in Alcott’s ‘A Marble Woman,’” in Robert K. Martin and Eric Savoy,

editors, American Gothic: New Interventions in an National Narrative (Iowa City: University

of Iowa Press, 1998), pp. 183-201.

9 Katie Roiphe, “Making the Incest Scene,” Harpers (November 1995).

10 Biel mentions gothic incest (actually twice) but attributes it mostly to my imagination:

Biel, American Gothic, p. 52-53; interestingly, that section in his book related to incest is

picked up in a review of the book: David Mehegan, “Goth Chic,” Boston Globe, May 21, 2005

(http://www.boston.com/ae/theater_arts/articles/2005/05/21/gothic_chic/?page=full);

R. Tripp Evans, in his majesterial and immensely admirable Grant Wood: A Life (New York:

Alfred A. Knopf, 2010) forwards incestuous mother-son readings of Woman with Plants (pp.

89-90), Portrait of Nan (278-9), and Parson Weems Fable (277-8), and he mentions that

American Gothic is “haunted” by incest and seems to present a “vaguely incestuous scene”

(pp. 92, 94; see also 77), but he doesn’t press or explain at all an incestuous reading of

American Gothic, as he does the other paintings under review.

11 And, before those advertisers recuperated the image, the painting was enlisted as a war

recruitment poster for WWII, substituting the title “American Gothic” underneath by the

3

15

banner, “Government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from

the earth.”

12 Matthew Baigell, The American Scene: American Paintings of the 1930’s (New York:

Praeger, 1974), pp. 110.

13 James M. Dennis, Grant Wood: A Study in American Art and Culture (New York: Viking,

1975), pp. 229-35.

14 Corn, Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision.

15 Wanda M. Corn, “Grant Wood: Uneasy Modern,” in Grant Wood’s Studio: Birthplace of

American Gothic, edited by Jane C. Milosch (Munich, Berlin, London, New York: Prestel,

2005), p. 125; Evans, Grant Wood: A Life, p. 103.

16 Robert Hughes, “American Visions,” Time magazine (Special Edition 1997); and Robert

Hughes, American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf,

1999), p. 439.

17 John Seery, “Grant Wood’s Political Gothic,” Theory and Event (Johns Hopkins University

Press, Muse Project--on-line journal), vol. 2, no. 1, March 1998.

18 Henry Adams, “The Truth About Grant Wood,” College Art Association annual conference,

New York, February 26, 2000.

19 Evans, Grant Wood: A Life.

20 James H. Maroney, Jr., Hiding in Plain Sight: Decoding the Homoerotic and Misogynistic

Imagery of Grant Wood (Leicester, VT: Gala Books, 2013):

http://jamesmaroney.com/art/grant-wood/Hiding_in_Plain_Sight_full.pdf

21 Thomas Hoving, American Gothic: The Biography of Grant Wood’s American Masterpiece

(New York: Chamberlain Brothers, 2005)

22 Corn, “Grant Wood: Uneasy Modern,” p. 124. Corn sees Suckow’s treatment of the farm

spinster figure as tragic, but she sees Sigmund’s treatment as comic. She references

Sigmund’s poems “The Serpent” in this regard and also mentions his “Hill Spinster’s

Sunday.” But as I read the latter, I read the sexual frustrations and dreams of a spinster,

which aren’t particularly humorous. I also see Sigmund’s broaching the themes of:

temptation (“Tempted”); pressures on farm women for procreation (“Maize Country Natal

Day”); a rebellious minister’s wife (“The Minister’s Wife”). I don’t detect much comedy in

those vignettes. And I certainly don’t agree with her assessment that his poem “The

Serpent” is a comic depiction of the spinster figure; I find the register regarding the

spinster’s hypocrisy and mien as caustic and damnable. In the film, “This American Gothic,”

Corn contends that the spinster daughter theme reflected a concern about children taking

care of elderly parents. I think these accounts minimize the salaciousness of the spinster

figure in the works of Suckow, Sigmund, and Wood. Ruth Suckow, “Best of the Lot,” Smart

Set 69 (November 1922), pp. 5-36; “Midwestern Primitive,” Harpers Monthly Magazine 156

(March 1928), pp. 432-42; “Spinster and Cat,” Harper’s Monthly Magazine 157 (June 1928),

pp. 59-68; Jay Sigmund, “The Serpent,” Frescoes (Boston: B.J. Brimmer, 1922), pp. 40-42;

“The Minister’s Wife, Frescoes, pp. 36-38; “Hill Spinster’s Sunday” in Jay G. Sigmund: Select

Poetry and Prose, Paul Engle (ed.), (Muscatine, Iowa: Prairie Press, 1939), p. 19; “Maize

Country Natal Day,” in Select Poetry and Prose, pp. 27-28; “Tempted,” in The Plowman Sings:

The Essential Fiction, Poetry, and Drama of America’s Forgotten Regionalist Jay G. Sigmund,

Zachary Michael Jack (ed.), (Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Plymouth, UK:

University Press of America, 2008), p. 64. Evans also discounts any “hint” of sexuality in a

16

father-daughter pairing in American Gothic, attributing it to “inevitable (if ironic) jokes

about promiscuous farmer’s daughters.” Evans, Grant Wood: A Life, p. 101.

For some of this 19th century demographic information about Iowa, see:

http://publications.iowa.gov/135/1/history/7-1.html; and

http://www.kindredtrails.com/Iowa-History-2.html

23

Nan Wood Graham, with John Zug and Julie Jensen McDonald, My Brother, Grant Wood

(Iowa City: State Historical Society of Iowa, 1993) p. 76.

25 Dorothy Dougherty, “The Right and Wrong of America,” Cedar Rapids Gazette, September

6, 1942.

26 Corn, “Grant Wood: Uneasy Modern,” p. 125; Evans, Grant Wood: A Life, p. 103

27 Evans, Grant Wood: A Life, p. 129.

28 Those who associate Gothic arches with high-European religiosity (along with high

European cathedrals) might be forgetting that the word gothic was coined and applied to

such arches as a term of abuse. The new gothic arches allowed stonemasons to build taller

churches than Roman arches had allowed; but the fifteenth century Italian writer Vasari

found the new arch architecture to be ugly and barbaric—as if built by “Goths,” those

barbarians who had once ruined Roman civilization. See Goldstein, Grant Wood: American

Gothic, p. 13.

29 Grant Wood said that he admired and studied assiduously the Gothic painting style of

fifteenth-century German-Flemish painter Hans Memling. Irma René Koen, “The Art of

Grant Wood,” Christian Science Monitor, March 26, 1932 (cited in Jane C. Milosch, “Grant

Wood’s Studio: A Decorative Adventure,” in Grant Wood’s Studio, p. 104). See also

Goldstein, Grant Wood: American Gothic, p. 23.

30 Goldstein, Grant Wood: American Gothic, pp. 36-7.

31 Evans is very good on this point of the man’s slightly averted gaze. Grant Wood: A Life, p.

97.

32 Sigmund, “The Serpent.”

33 See, for instance, Robert K. Martin, “Haunted by Jim Crow: Gothic Fictions by Hawthorne

and Faulkner,” in American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative, pp. 129-142.

34 Evans is particularly good on the Medusa imagery. See Grant Wood: A Life, pp. 101-2 (and

also pp. 126-7),

35 Ibid., p. 79.

36 Ibid., p. 80.

37 Ibid., p. 89.

38 Ibid., p. 88.

39 Ibid., p. 57.

40 Ibid.

41 I’m greatly influenced here by the psychoanalytic framework proffered in Michael

Rogin’s reading of Herman Melville’s novel Pierre, or, The Ambiguities—a novel that turns

on an incest plot. Michael Rogin, Subversive Genealogy: The Politics and Art of Herman

Melville (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985).

42 See my “Stumbling Toward a Democratic Theory of Incest,” Political Theory, vol. 41, no. 1

(February 2013), pp. 5-32.

24

17

For what it’s worth, Rogin points out that siblings Pierre and Isabel “coiled together” like

the rope-snakes of the Medusa head. Rogin, Subversive Genealogy, p. 174. (Special thanks to

Shayna Citrenbaum for alerting me to this connection, and many others.)

44 See Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York:

Routledge, 1990); and Butler, Antigone’s Claim: Kinship Between Life and Death (New York:

Columbia University Press, 2000).

45 If anything, the pointedness of the sansevieria trifasciata or snake plant is gendered in a

female direction, commonly referred to as “mother-in-law’s tongue.”

46 Evans, Grant Wood: A Life, pp. 84-8.

47 Ibid., p. 86.

48 Ibid., p. 95.

49 Evans talks about the conflation of Satan and Hades in Western art and literature, but he

seems to enact that conflation by mentioning Dante’s Inferno along with a suggestion about

“Hades’ fiery world”—and all of this is in support of a reading of American Gothic as an

underworldly pairing of Persephone and Dis/Satan. Yet one is reminded that Dante’s

Inferno, at the bottom, is not a place of fire, but rather cold ice. Ibid., p. 100.

50 Ibid., p. 101

51 Ibid., p. 103

52 Ibid., p. 128.

53 Evans doesn’t apply this sister-substitution thesis of his to his analysis of American

Gothic: If Wood is imagining himself as female-sister-figure in American Gothic, then the

attempted reconcilation with the father isn’t depicted/imagined as a man-to-man

reconcilation; rather, it would fall under the visual, if ambiguous, auspices of a putatively

husband-wife pairing (today, one might detect transgender inklings in Wood’s psychic

substitution). In my own 1998 piece (“Grant Wood’s Political Gothic”) I do suggest that

Grant Wood was the true spinster—around whom town gossip circulated—at the time he

painted American Gothic, and thus his own identification with the female figure in the

painting may have been strong. Following through on that point, we would have to retain

more than a hint of an incestuous coupling, a father to son pairing, now wedded, as it were,

under the terms of the painting’s conventions.

54 Evans observes allusions to Eve the temptress and to biblical accounts of the fall from

Eden in Arnold Comes of Age, Portrait of Nan, and Parson Weems’ Fable, but he doesn’t make

those associations with the snake plant in Woman with Plants and American Gothic. Evans,

Grant Wood: A Life, pp. 278-9.

55 Perry cites a number of works associating the gothic with incest: Perry “Incest as the

Meaning of the Gothic Novel.”

56 Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley

(New York: Vintage books, 1978), pp. 106-7.

57 Perry, “Incest as the Meaning of the Gothic Novel,” pp. 269-70.

58 Gilian Silverman (writing about Pierre) also has a problem with positing incest as a

stand-in for homoerotic desire. Silverman, “Textual Sentimentalism: Incest and Authorship

in Pierre,” American Literature, vol. 74, no. 2 (June 2002), p. 363.

59 Monnet uses the figure paradiastole to describe American Gothic’s visual-narrative

strategy of calling into question the moral terms by which one identifies a wrong-doing as

wrong. Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet, The Poetics and Politics of American Gothic: Gender and

43

18

Slavery in Nineteenth-Century American Literature (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing,

2010), pp. 11-13.

60 I import the term “protest painting” from Monnet’s analysis of Melville’s Pierre as a

“protest novel.” She doesn’t use that term with respect to American Gothic, but her analysis

of Pierre is consistent with her analysis of Wood’s painting: “…it is not necessary to insist

on reading the incest theme literally as a veil for homosexuality. Incest itself is a very queer

and important source of radical probing of conventions in the gothic. Generally, the way

that the gothic deals with incest is as a complex problem rather than a shocking taboo. It

often invites readers to undermine the absoluteness of strictures against its perpetrators

rather than reinforce them….It is also possible to see the incest theme as a synecdoche for

illegal sexuality in general. In this light, Pierre dramatized the hypocrisy and repressiveness

of persecuting people for loving outside of social conventions (which the book exposes as

nothing more than codified ideals that few real people actually live up to). This reading

views Pierre as a kind of protest novel, decrying hypocritical intolerance for sexual lapses

in general….” Monnet, The Poetics and Politics of American Gothic, p. 88.

61 Richard Rorty, Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America

(Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1998), pp. 94-95.

62 Bonnie Honig, Democracy and the Foreigner (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University

Press, 201), pp. 115-22.

63 Ibid., p. 119.

64 Steven Biel is right, in other words, but he needs to theorize the undecidability that he

oversees.