A Speech Act Analysis of Christian Religious

advertisement

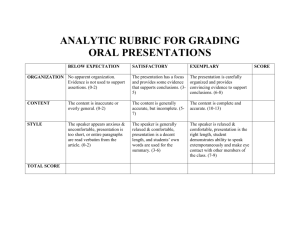

A SPEECH ACT ANALYSIS OF CHRISTIAN RELIGIOUS SPEECHES By Sola Timothy Babatunde (PhD), Department of English, University of Ilorin, Ilorin. INTRODUCTION The utilization of the contributions of linguistics, philosophy, psychology and sociology in the examination of how language is used to mean in communication generally has always been a rich and rewarding exercise. This is especially so in Christian religious communication. This chapter does a semantic analysis of evangelical Christian religious speeches, using the speech act theory of meaning. Precisely, our attention is focused on the following aspects of evangelical religious speeches: (a) The influence of context in religious communication; (b) The organisation of the message and the intention behind this organization; (c) The possible areas of misunderstanding and communication break-down , and how participants incommunicative process endeavor to guide against this (breakdown); (d) The role of audience in influencing the message of the speaker and its presentation; and lastly, (e) Audience participation and the overall reaction of the audience to speaker and his message. The speech act analysis is limited to Evangelical Christian Religious Speeches (ECRS) and the data collection is restricted to Ilorin. Four main speeches/sermons of about thirty minutes are used; two recorded speeches delivered in a situation of interpersonal (face – to – face) communication, and the other two transmitted through the radio (courtesy of radio Kwara Christian religious programme producer). In discussing our findings, we have referred to other speeches outside the main ones and cited examples that will assist in explicating our analysis. The frequency table of 1 speech act types presented at the end, however, involves only the four main speeches analysed. Tape – recorded, orally delivered speeches are used in the study because of the established primacy of speech in linguistics. The speech act theory proposed by Kent Bach and Robert M. Harnish (1979) as been mainly adopted for this study. The Bach and Harnish theory is more comprehensive, in our view, than those of Austin and Searle. Bach and Harnish lay emphasis on intention and inference, and the theory provides a schemata through which one understands the process where by the audience infers the illocutionary force in a speech act. We also see the Bach and Harnish theory as informing the inferential theory proposed by Allan (1986). As such Allan’s updated version becomes relevant in specifying, in an informal way, the stages in hearer’s reasoning to infer the speaker’s message (1986:251-252). In addition, the Bach and Harnish theory does not seem adequate to account for the undertow current of speech act that coordinates all the other speech acts in a connected discourse and it does not seem adequate in accounting for the overall pragmatic, sociological, historical and linguistic factors that are usually in operation in a communicative situation: the emphasis of the theory appears to be on the immediate context of the social exchange. For these reasons, we shall adopt Adegbija’s master speech acts theory which recognizes the importance of the non – immediate context of discourse’, and is adequate in accounting for meaning in a second language situation (English as a second language, ESL). In short, Adegbija proposed a pragmasociolinguistic context which captures the cultural, historical and psychological backgrounds of the context of communication which are important in analysing the speaker’s intention and specifying the hearer’s inference. In all, the master speech act theory looks at a piece of connected discourse as a single speech act, while the individual speech acts in the discourse are concatenated to achieve a recognizable illocutionary act. This idea, we shall see later is important in helping us to recognize the overall illocutionary act performed in Christian religious speeches .Thus, we intend to do a semantic analysis, only with emphasis on the speech act theory. Since the research is a semantic 2 analysis, we shall occasionally draw on any useful contribution of linguistics to meaning explication. The audience or hearer (s) in this essay, unless specially qualified , refers to two groups of people : the first group consists of those members of the audience that share the same belief with the speaker /preacher. The message is meant to give this group more information that will confirm their belief; these are the believers. The second group consists of the unbelievers, those who do not share the same belief with the speaker. These have their various degree of tolerance for the speaker’s message. The speaker’s intention is to persuade this group to share his belief. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND The study of meaning, semantics, though relatively new in linguistics , is bedeviled by a cross- current of theories and approaches mainly because of its amorphous nature. The study of meaning cannot be avoided because it is a crucial factor in communication. The approaches to the description of meaning vary mainly because they are influenced by two variant philosophical constructs -- behaviourism and mentalism. There is no space to review these in this short chapter. We shall only point out the aspect of the Speech Acts Theory that has been used in this study. The Speech Act Theory, first proposed by Austin , is an attempt to bridge the gap between the philosophical and the sociological approaches to semantics. Its main tenet is a consideration of the social and linguistic contexts of language use. The final version of Austin’s theory was published in 1962. Austin does not separate the phonic medium from the non –linguistic medium because of his recognition that the non – linguistic medium is superimposed on the linguistic either to reinforce or contradict it. Austin’s analysis starts with establishing a distinction between constative and performative utterance. Constatives are utterances /statements that can be either true or false. They constitute only one part of meaningful utterances. Performatives, on the other hand, have no truth value. When a performative utterance is made, one has 3 already engaged in an action , a speech act. For instance, by saying “I nominate you head boy of the school”, a speech act has already been performed by the utterance. Essentially, this is the distinction drawn between saying something and doing something by the use of language. Performatives, Austin asserts, should be brought under the scope of logical and philosophical investigation. Austin differentiates between locutionary, illocutionary and perlocutionary acts. i. A locutionary act is the production of meaningful utterances; The utterance of certain noises, the utterance of certain construction, and the utterance of them with certain “meaning” in the favorite philosophical sense of that word; i.e. with a certain sense and a certain references. (Austin, 1962: 94) ii. An illocutionary act is an act performed in saying something. iii. A perlocutioanry act is an act performed by means of saying something; persuading someone to believe that something is so. It concerns the effects of the act of saying something. Austin did taxonomy of speech acts. He has five; verdictives, behabitives, expositives, exercitives and commisives. John Searle‘s philosophy of language is mainly contained in is book, Speech Acts: An Essay on the Philosophy of Language, published in 1967. His hypothesis is that in speaking a language, one is engaging in a rule –governed activity. He says it is a matter of convention that a particular expression performs a particular action. Searle claims that a speech act is an intentional behaviour . He adds that being understood but not producing effect is the goal of speech acts. To explain the rule –governed hypothesis of language, Searle talks of two rules : constitutive and regulative rules. Constitutive rules constitute (and also regulate) an activity the existence of which is logically dependent on rule. Regulative rules, on the other, regulate pre-existing activities whose existence are logically independent of rules. Searle’s theory of speech acts is powerful because it combines Austin’s conventional theory and Grice’s intentional theory of meaning. However, the intentional theory is 4 problematic, for the intention to produce an effect cannot be overlooked in an adequate account of illocutionary acts. Some other defects have also been identified by Adegbija (1982). For instance, he observes that Searle’s focuses just on specific acts and not on the complexity of acts such as deductions, explanations, etc. We shall not dwell on the comments on Searle’s theory in detail here, but it is just important to note that some of the observed limitations of Searle’s theory serve to ignite research work in the speech act theory of meaning. Bach and Harnish‘s theory is an intention and inference approach to communication. Bach and Harnish argue that before somebody communicates, he has something in mind, he has an intention and his belief is that the hearer should recognize this intention. Bach and Harnish see linguistic communication as an inferential process, and “the inference the hearer makes and takes himself to be intended to make” depends on what the speaker says on the “mutual contextual beliefs “(MCBs), the important contextual information the participants share together. The hearer relies on MCBS to determine the meaning of what is uttered and also the force and content of the speaker’s illocutionary act. Bach and Harnish contend that two types of inferences operating in communication can lead to two types of acts: the direct and indirect speech acts. The former involves the literal strategy of analysing a speech act. The indirect inference looks beyond the literal meaning of the act to understand the speaker’s intention. It is the belief which the speaker and hearer share that enables them to communicate effectively in this situation. In their theory, Bach and Harnish talk of the speech act schemata (SAS), an organisation in the brain that concerns some information one already has which enables one to decode a speech act. In addition to MCBs, Bach and Harnish recognize two other general beliefs, the linguistic presumption (LP), and the communicative presumption (CP). LP refers to the mutual belief in a linguistic community that whenever any member utters an element of that language, the hearer, who is also a member, knows the meaning of the 5 element. CP refers to the mutual belief that a speaker who performs a speech act actually has an intention which he wants the hearer to recognize. So, if a speaker says something, he is believed to be performing a recognizable illocutionary act. A thorough study of Bach and Harnish‘s theory shows that they have provided a comprehensive step by step analysis of the process which a learner goes through in an attempt to identify an illocutionary act. As Adegbija 1982) has observed, however, the process may not be discreet as the SAS suggests. Bach and Harnish’s theory also provides an idea of how meaning is perceived in indirect speech acts. There, however, appears to be an undue emphasis on the perception of the speaker’s intention before communication can take place. Cohen (51) observes that intention is not enough in understanding illocutionary acts. As the theory stands, a number of aspects, like the MCBs, need to be further developed and characterized. Bach and Harnish have outlined taxonomy of illocutionary acts. They have communicative and non-communicative illocutionary acts. The non-communicative illocutionary acts are also referred to as the conventional acts; the affective and the verdictives. These affect institutional states of affairs-thus they are conventional. Bach and Harnish argue that conventions “are actions which, if done in certain situations count as doing something else”(109) . Bach and Harnish propose four categories of communicative illocutionary acts; Constatives, Directives, Commisives and Acknowledgements. They have a long list of the types of acts which fall into each of the categories. The analysis based on these categories is presented as Appendix One at the end of this chapter. Bach and Harnish’s conception is that the fulfillment of illocutionary intents is in the recognition of the attitude expressed by the speaker, and types of illocutionary intents correspond to types of expressed attitudes. Illocutionary uptake and perlocutionary effect are achieved if the hearer forms a corresponding attitude that the speaker intended him to form. It is this expressed attitude and its achievement that forms the backbone of Bach and Harnish taxonomy. 6 Adegbija , in an unpublished paper titled “What is semantics in English as a Second Language (ESL)?” calls for a unified theory of meaning explication after pointing out the inadequacies of earlier theories. This call had earlier on been made in Adegbija where he argues that illocutionary acts need not always be conventional; that variables like intention and the pragmatics of the situation of interaction are very important. Adegbija says the pragmatics of the situation of interaction may include the following: - the cognitive of affective states of the participants - special relationships obtaining among participants, like husband and wife, etc. - presence of lack of mutual beliefs and understanding - the nature of the discourse and the relationship of this to the interest of participants. - World knowledge, both specific and general. He refers to the aggregate of the linguistic act resulting from the global context of an utterance as the master speech act. The whole gamut of contextually relevant factors in discourse is referred to as “pragmasociolinguistics context”. Adegbija proposes three layers of meaning: (a) The primary layer handles literal meaning in utterances. (b) The secondary layer is concerned with indirect aspects of meaning, this can be inferred from the immediate context of an utterance. It also takes care of area of pragmatics like implicature, presupposition, etc. The tertiary layer is the master speech act level of meaning which handles the non – immediate context of an utterance, which is the pragmasociolinguistic aspect of utterance. The three layers are seen as aiding one another in describing meaning. It has the merit of handling meaning in both the L1 and L2 situations without attempting a modification of the theory. However, as the theory stands, it may give the impression that each of the layers is discreet aspects of semantic description in reality, which I fear , is not so. The process by which the brain interprets utterances is not as discreet as the model seems to suppose; for in most cases, one is not conscious of interpreting the literal meaning 7 in indirect speech acts before considering the secondary meaning. The entire process is a continuous event which varies in depth in accordance with the level of competence of the decoder. In spite of the above, the theory proposes a comprehensive approach to meaning, which calls for a further development. It attempts to simplify an intellectual explication of meaning, for it pin points those variables we should pay attention to. Allan’s submission is on the assumption that the speaker (S) constructs his utterance (U) with the intention that the hearer (H) can reason out his message in the context in which it is uttered. He therefore presents the following as a model of the stages in H’s reasoning: a. Perception and recognition of S’s utterance as linguistic. b. Recognition of U as a sentence element of language spoken with the appropriate articulation and having the senses of a locution. The CP is said to be involved at this point. c. Recognition of S’s proposition by matching the locution to the world spoken of. The theory of denotation is deployed here. d. Recognition of the primary illocution of U on the basis of the form of the locution and the definition of illocutionary acts which form part of the theory of speech acts. e. S’s presumed reason for performing the primary illocution is sought in the light of various assumptions and presumptions of the CP, knowledge of language (L) and use of L. f. The illocutionary point of U, i.e. S’s message in U, is recognized when at last no further illocutions can be inferred. (Allan, 1986: 251-252). Allan’s submission rests on the premise that “speech acts are pragmatic events that can only be accounted for satisfactorily within a theory that takes account of pragmatic factors” (280). 8 DATA ANALYSIS INTRODUCTION Hypothetically, the encoder of a religious message has some intentions which he wants the audience to recognize. We can also assert that behind every Christian religious communication is the speaker’s intention to persuade the audience; for Christian religious communication is directed towards the beliefs of the audience – the speaker believes something and wants the audience to share this belief. The speaker then persuades his audience, modifying their attitudes and beliefs towards an intended direction. Also, mutual contextual beliefs (MCBs) function in a situation of Christian religious communication. MCBs are the important contextual information the participants share together. As we shall show later, the speaker relies on MCBs to achieve parsimony in his speech. Bach and Harnish are of the view that illocutionary acts are understood by the audience through an inferential process. In their speech act schemata (SAS), Bach and Harnish talk of the hearer (H) understanding the ‘operative meaning ‘ of an utterance .( Bach and Harnish 20). With the aid of the CP and MCBs, the hearer makes a choice of what the speaker actually means among the possible ‘meanings’ of the utterance. Concerning implication, McCawley (245) says “what is conventionally implicated by an utterance depends not only on the utterance but on what other utterances the speaker could have produced but did not ‘. Also, Allan recognizes a possible range of illocutions which H can infer from U; and this is a factor of the whole gamut of the contextual experience of H. This is the basis of all our analysis in this chapter. Also, in a body of discourse, the understanding of a speech depends on the understanding of the other speech acts in that context. This a hint at the importance of inter speech act connections in making inferences (Adegbija 143). Concerning the relationships that exist between implicature and presupposition, Adegbija says ‘working out an implicature is crucially dependent on the awareness of 9 the speaker and the hearer on the presuppositions of the content of interaction ‘(Adegbija, 1982:174). Implicature, a ‘sophisticated inferential procedure’, is only possible through understanding the presuppositions of a situation of social interaction’ – the pragmasociolinguistic context. Among the basic presumptions the audience make in a given religious communication situation are the following: 1. There is a mutual belief that the speaker who performs a speech act actually has an intention to say something- a ‘new s’ for the audience. 2. The audience presumes that the speaker is capable of handling the topic. This does not mean that the audience will not be critical enough to perceive lapses in the speech act, which can lead to communication break down. 3. Lastly, the audience presumes that the speaker is telling the truth and that the speaker has a good intention. Here the audience is usually conscious of the Bible passages referred to and the interpretation offered by speaker. The separate analysis of the two groups of data (i.e. face to face interpersonal communicative situation and the radio message) which follows, it to enable us state with clarity, the influence of context on evangelical Christian religious speeches and perhaps on language use generally. Context is a major variable recognized to be essential by the speech act theory of meaning explication. 3.2 Features of Face –to –Face Interpersonal Evangelical Christian Religion Speeches. What are the peculiar features of evangelical Christian religious speeches delivered in the context of interpersonal face-to-face communication? How does the speaker manipulate his language and the speech as a whole? How does the audience infer the illocutionary intent of the speaker? How does the audience factor affect the entire presentation? We shall offer some answers to these questions now. As we highlight the outstanding features of the speeches, we shall do some analysis of the examples used. The sample analysis will illustrate the entire analysis presented in Table 1. 10 1. Acknowledging The Existence Of God Speakers acknowledge the existence of God by thanking him for one thing or the other. We shall illustrate this with an example from the speech titled “Christians and Cults”(cc). The speaker opened his speech with the utterances: Example1. I thank God for giving me the privilege of being with you this afternoon. The illocutionary act type is Acknowledgement: Thank. The speaker exploits the following mutual benefits: i. That (a) God exists; ii. That the God expects a show of appreciation from man (MCBs); iii. That it was a privilege for the speaker to be there at that time; i.e. either that somebody else might have stood in his stead or that something might have disturbed him from standing there. These inferences are made because of world knowledge and the belief between the speaker and the hearer: i.and ii. rely on the social context of the speech; it is a meeting of people who share a mutual belief in the existence of God. It is also a Christian injunction that we must give thanks of God for everything. The speaker expects that the audience will realize his intention to act in accordance with this tacit belief. The speaker also observes that it was an afternoon. This hints at the tendency to state a fact that the audience is aware of ;not informing , but only making a mutually perceivable observation. Speakers do not always express their acknowledgment in such straight terms. In the speech titled ‘ Holiness unto the Lord” (H.L), the speaker spent about five minutes acknowledging the presence of God by explaining that he is the source of all blessings, and assuring his audience of mighty blessings from God. There is another example, from the speech titled “The Blessings in Giving ‘ that is particularly interesting. The first utterance of the speaker was ‘ I thank God because he will use you mightily to bring about a revival’. It is interesting because it combines two illocutionary 11 acts: Acknowledgement and Constative. This is a case of speech nesting. The speaker makes some presuppositions: i. God brings about revival by using people; ii. The audience constitutes the sort of people God uses to bring revival; iii. The speaker has enough grounds to believe the proposition which the audience will also understand; iv. One can thank God for something God has not done, but which one believes he will do. The combination of thank and prediction emphases the prepositional content by assuring the audience that the speaker really means the prediction. The acknowledgement, ‘I thank God’ makes the proposition felicitous by confirming that the speaker actually believes that P (and he wants his hearer to believe that P). The acknowledgment of the existence of God contributes to the communicative process by setting the mood, and assuring the audience that they have not come to the wrong place. The acknowledgment and the recognition that God is the source of all blessings help to establish a common ground of reference between the interlocutors. 2. A Statement Of Purpose. In most cases, after rapport with the audience, the speakers state what they want to do. In CC, the speaker tries to limit the focus of the speech by introducing another term ‘occult’. The speaker gives a simple information in the utterance, “the word ‘cult’ is a very broad one, it’s a very broad one “. It is an attempt to describe ‘cult’ and information is given about the scope of the word. The utterance is somewhat ambiguous because apart from it being informative, it is also assertive, and the repetition of ‘it’s a very broad one’ is given to confirm the assertive illocutionary act. Taken in context, the above utterance limits the scope of the speech and the speaker introduces another word, “occult”. He then emphasizes his justification for bringing in the new word, which explains the emphasis on the broadness of the initial topic given to him to speak on. This background will enable us understand better the commissive act that comes up later in the speech: 12 “So I will talk about the Christian and the occult.” With this utterance, the speaker commits himself to a future course of action. From the speech act above we can infer that: i. the speaker is allowed to limit the focus of his speech; ii. the speaker believes the audience will be interested in the ‘new’ topic ; and, iii. the prepositional content of saying what the focus of the speech is in order. The speaker has channeled a course for himself, and the audience will evaluate his contribution in line with how faithful he as to promise. H.P Grice (1975:44) will insist the speech act (commissive) should be examined on its overall contribution unto the entire discourse. As can be seen, the illocutionary intent is that the audience knows the focus of the entire discourse. In HL the speaker repeats the topic several times and ‘directed’ the audience to repeat it too. Apart from emphasizing what the object of the speech is, he achieves audience participation. 3. Developing the Discourse. The speakers tend to introduce a number of stylistic devices in the development of their speeches. In one way or the other, the devices help to reinforce the truth value of the claims made: all in the bid to persuade the audience. Among the common device are the following: a. Allusions, references and testimonies. Speakers at times make passing references to incidents they are familiar with to augment their discussions. An example is taken from CC, where the speaker refers to an incident about the woman who went to Jerusalem. He makes this reference to help him explain better what he refers to as “real Christian”. Let us analyze the first utterance of the allusion: “I know one Christian woman who has been to Jerusalem”. (Constative) The prepositional content is that the speaker is expressing knowledge, thereby making a claim that he actually knows that woman. The utterance has two speech acts. Going by Chomsky’s transformational generative grammar (TGG) the sentence has two 13 sentences in its deep structure: i. I know a Christian woman. ii. The woman went to Jerusalem. The process of embedding has taken lace to give us this surface structure and the coreferring coordinator, ‘who’, conjoins the two sentences. The first clause is an assertive. It helps to assure the audience that the speaker is making a personal claim. The illocutionary act of the dependent clause, on the other hand, helps the speaker to inform the audience about what he (the speaker) knows. The following inferences can be made from the utterance: i. Jerusalem has, at least, a historical significance for Christianity (Basis: World Knowledge). ii. There is a practice that a visit to such a place has a religious significance, (Basis: MCBs). iii. Some people believe that some one who visits such a place is a faithful proselyte (Basis: MCBs) The speaker wants to ensure that the audience infer his illocutionary intent so he asks, “She is a good Christian, isn’t she?” He then concludes the allusion by asserting that a visit to Jerusalem does not make one to be a good Christian. In all, the allusion helps the speaker to make his point easily. Stories, anecdotes and Biblical allusions help speakers to validate the truth value of their claims. The dramatic presentation of stories brings life into the discourse (speaker mimic actions and speech patters); the allusions give vivid descriptions which appeal to the imagination of the audience. A clear example is the story of the philosopher who wanted to know whether there is really anything like witchcraft (see’ Christian and Cults’ (CC)). The allusions and testimonies are made appropriate by a direct relation to the discourse. The audience then makes an immediate appreciation of the contribution of the stories to the overall development of the discourse. 14 (b)Other Rhetorical Features Questions: Speakers try to establish a normal conversation thus, they ask some rhetorical questions. At times, some sort of response is expected from the audience, but these non-verbal responses like asking the audience to signify something with the raising up of hands etc. But in most cases, the questions are rhetorical ones that don’t expect a reply from the audience. The intention is to establish an interpersonal communicative mood which will make both the speaker and the hearer active participants in the communicative process. Again, we are taking an example fro “CC “Do you know how they were passing these spirits around the school?” (A Directive: Question). Specifically, the prepositional content is aimed at making the audience visualize how the familiar spirits pass their spirits around the school. The speaker perceived that the audience was becoming too relaxed and too inactive, so he found a way of involving them. This question can be framed in another way to illustrate what the speaker expected: Do you want to know how they were passing their spirits around the school? This interpretation of the question is borne out of the view that the speaker wanted to arouse the interest of his audience in the story he was about to tell them. We have another example in “Holiness Unto the Lord”(HL). The speaker noticed that the audience was getting relaxed and distracted by his gesticulation, and therefore asked, “Are you getting what I’m saying?” This is a direct question that would have called for an answer, but because of the context, both the speaker and audience were aware of the act that no direct answer was required. The principle that was in operation was “silence means consent”; since no one said ‘no’ it meant the answer was in the affirmative. The speaker intended to achieve the perlocutionary effect of rousing the audience from their passive enclave. Before the question was asked, the speaker had been explaining a crucial point about holiness. His voice got to a peak, such that he needed to relax his voice. The question, therefore, helped to bring in this desirable pause. When the speaker continued again, the voice was low and it started rising gradually. Whenever the speaker felt the need to take a pause he would drag the 15 third and the penultimate words ending a sentence e.g. “holiness un – to – the – lord”. This is also done for emphasis. ii.Repetition: Another rhetorical device employed in the Christian religious speeches is repetition. From CC we have the following examples: (a) The word ‘cult’ is a very broad one, it’s a very broad one” (b) That he could smell something terrible, a terrible smell Example (a) was analyzed earlier, we shall then analyze (b) here. It is a Constative: Description. The speech act is taken from the story of a philosopher who wanted to test for existence of witchcraft; ‘he’ then refers to the philosopher. Before I proceed with the analysis, it is pertinent to mention the presence of inter-speech act connection. It is a feature of an orally delivered speech which is a carry – over from a grammatical element of loose inter – sentential connection recognizable in spoken utterances. Because of the loose connectives, it has to refer to the previous speech act if the speech act it is heading will be meaningful. The same thing is applicable to the pronoun he. “that he could smell something terrible, a terrible smell”, is a Constative and the propositional content describes the subject’s (he) olfactory feeling. The lexical collection of the speech act deserves some attention : ‘Smell’ and‘ Terrible’ occur twice in the speech act, and they perform different functions at each occurrence. The initial occurrence of ‘smell ‘is a verb, while the second occurrence is a noun; ’terrible‘ is an adjective, a qualifier in the first occurrence, whereas it modifies ‘smell’, a noun , in the second occurrence. Though instances of these are eh exception (perhaps not the rule),the variation functions stylistically by introducing ‘elegant’ variation into the discourse, thereby emphasizing the speaker’s illocutionary intent. ‘terrible’ and smell collocate to intensify ‘smell’ something terrible;’ terrible smell’ expresses the speaker’s intention better because the modifier is close to the modified noun, “smell, unlike what operates in ‘smell something terrible’ – it is rather mild here, not forceful. 16 In HL we see another mode of repetition; the speaker keeps hammering on ‘Holiness unto the Lord’, which is the topic of discourse- no variation in lexis. iii.Tonal Variation : Tonal variation is a feature superimposed on the lexical items in a speech act, thereby intensifying the illocutionary force of the (speech) act. It is used for emphasis: a sudden fall in tone has an additional effect of getting the attention of the audience; the audience is made to listen keenly. Tonal variation is also employed to give a threat. It may be a threat to a part of the audience. For instance, in H.I, the speaker said,”If you are not holy, you will not see the Lord”. The threat is directed more to those who are not living in holiness, though those who are already in holiness received as assurance that they will see the lord because they have met, at least, one of the conditions for seeing it. 3. Lexical and Semantic Features Certain lexical items /features assume a sort of rhetorical significance which speakers use to advantage. Some lexical items assume ‘special ‘semantic connotations in religious utterances. They are the lexemes of a group and speakers exploited the mutual belief that the hearers would understand the connotations. For example; “They said we should reach out and convert people” (Constative: Informative). The intention was to inform by reporting. (The example is taken from CC).The connotations of ‘reach out’ and ‘convert’ are significant. ‘Reach out’ in the Christian religious sense refers to the process of evangelization, going out to tell people about the Christian religion. ‘Convert’ is the process of influencing the hearer’s belief; such that the hearer accepts the speaker’s expressed belief. The speaker exploits the social context in presupposing that the audience will understand the strictly religious meaning of the lexical items; thus he did not offer to explain the meaning of the items. Other items found in the data collected are: i. Deliverance: set free from the domination of the evil spirits and sin 17 ii. Minister to need: preach the word of God to help solve somebody’s spiritual and physical problems. iii. Judgment day: reference to a day when Christ will bring all deeds of men for reckoning. iv. Reconciled unto God: to confess ones sins and decide to obey God. v. Separated unto God: to live ones life in accordance with the directions of God. These expressions are among the registers of the Christians religion, and in most cases they form part of the MCBs. Speakers also employ some lexical items which demonstrate an awareness of unbelievers and believers in the audience. Depending on the illocutionary intent of the speaker, the audience (and by extension, the world) is either divided or united. This feature is worthy of mention, because, as I shall illustrate, it serves an overall persuasive function. We shall first illustrate how the audience is united: “No one of us should be involved in such things!” (From CC) Directive: Prohibitive. The propositional content is that the audience should not be involved in spirits. The speaker wanted to show the evils of occultism and thereby advised his audience not to have anything to do with it. “us” shows a collective belief (belief that the members of the audience are all Christians), then there must be a collective action taken on occults. The speaker did not differentiate between those who are ‘real’ and ‘unreal’ Christians because he wanted the unreal Christians to associate themselves with the crowd, which is the first step towards taking a decision to be realistically and spiritually part of this group of real Christians; that is, ‘reconciling ‘themselves with God. The choice of the collective pronoun is a persuasive move on the part of the speaker. On the other hand, language is used by speakers to alienate, so to speak, the unreal Christians. Examples include: i. If you are a real Christian, you want a complete separation from the occult . (from CC) ii. Who is on the Lord’s side?(from “Who is on the Lord’s Side?”(WLS)) 18 Above all, God has said you will be saved (from “In times like this”(TT)). iii. Utterance (i) is both assertive and suggestive. The assertive is not very direct and it is more than a suggestion. The utterance can be grammatically and semantically severed into two: A. If you are a real Christian(conditional ) B. You want a complete separation from the occult. In A, the speaker puts ‘real’ before the noun, ‘Christian’ so as to affirm his illocutionary intent. The conditional element of the utterance divides the audience, and the world at large, into two camps-- those who lack a complete separation from the occult, and those who do not. It is only the real Christians that are expected to separate themselves from the occult. “Complete” is emphasized through a tonal rise, and the intention is to make it clear to the audience that it is not a partial separation that is advocate, but a complete one. ii. Who is on the Lord’s side? (Directive; Question) What roles are involved? what obligations are instituted? and what needs does this question presuppose? These are some of the questions we must address our minds to for a proper understanding of this speech act. On a first hearing, the audience casts themselves in the role of answering the question reflectively. The present tense, ‘is’ , points to the urgency of the need for this answer the question pre-supposes that there are two sides: the Lord’s and the other side which the speaker assumes the audience is aware of. Or, it is a matter of urgent choice. The speaker emphasized this question later in the discourse with the utterance.” Choose you this day whom you will serve” (Exodus32:26 and Joshua 24:15). There is an obligation contained in the directive. A verbal answer is not expected but a thoughtful one that will influence the belief of the audience. My argument is that the question at once recognizes the existence of two groups of people in the audience. The speaker intends to persuade his audience that they should belong to the Lord’s side, so he paints it attractively: iii. Above all, God has said you will be given if you give (A Retrodictive). 19 The illocutionary intent is that God really promised, and the speaker wants the audience to believe it .The speaker believes that the audience will not question the authenticity of his report for it is presupposed that he (the speaker) has a credible source of information. The proposition is that God will give to only those who give. The adverbial phrase, ‘above all’, endows the speech act with the quality of relative importance. The phrase functionally relates the speech act in which it is contained with previous speech acts. What, however, is of more interest to us, is the condition from God; only those who give will be given. The audience is aware of the conditional element and this knowledge potentially divides the audience into two groups, i.e. those who are to expect God’s provision, and those who are not to expect it. The audience is enticed by the blessings, thus they will endeavour to meet the precondition to expecting God’s blessings. iv. ‘The people of God shall be saved’ (Constative:Assertive). This is a strong assertive, rendered with a tone of finality; a definitive statement; “the people of God” and “be saved” rely on MCBs for clarity. The context will enable the hearer to infer the operative (intended) meaning of the utterance. Contained in whatever meaning one may give to “the people of God” is the information that God is only one of ‘those’ who have followers. If not, the restrictive noun phrase (NP) would be out of place and irrelevant. If God is not the only one with adherents, then it is likely that for members of the audience belong to those others who have people. It is with this NP that the speaker achieves a division of the world at large into, at least, two camps. But unlike all other examples examined in this section, the division has been done with a leaning , a preference expressed for one of the camps as being the better of the two .This preference is expressed here in the proposition that people of God are saved. It is germane, at this point, to mention the two connotations of ‘saved’ in Christian circles. The first connotation, which is not the meaning expressed in the speech act under discussion, refers to a situation whereby someone gives his life to 20 Christ, and is therefore saved from the destruction Christians believe will come when someone who does not accept Christ dies. The second meaning, as used here, refers to the protection Christians have from the looming dangers of living in this world. The speaker wanted the audience to understand he was referring to the second meaning and this is made clear if one considers this speech act in the context of other speech acts. The speaker tried to point a sordid picture of the situation in this life (what happens in times like this), and he slipped in an antidote for this sickly situation of the world; i.e. being one of the people of God and enjoying God’s protection. In all, lexical items are used by evangelical Christian religious speakers to show an awareness of two groups of hearers, but the items are used as persuasive devices, persuading the ‘unreal Christians’ that it is better to join the speakers camp. 4. Code - Switching Another feature of interpersonal face-to-face religions communicative situation in Nigeria is the tendency for speakers to code-switch. Code – switching is a sociolinguistic phenomenon bedeviled with the rumbling tides of definition. For our purpose, we shall describe code – switching as a situation when language users show a tendency to shift from the linguistic features of one language to another. Examples abound in ‘Christian and Cults’: “Iya Alakara” and “Pa da sehin, ko fi ehin wole”. These are Yoruba expressions employed because the speaker presumed there were some Yoruba speakers o\in is audience. We now analyze “Iya Alakara”. Contextually, the phrase was used when the speaker was discussing witchcraft. Semantically, the speaker had to use the Yoruba expression because the English translation, “the seller of bean cake”, does not capture the perlocutionary effect the speaker intended to arouse in the audience. Culturally, the speaker explicated the belief known to the audience that women who sell “akara” are known to practice witchcraft, at least, among the Yorubas. It is in analyzing this that one readily perceives “The tertiary layer” proposed by Adegbija (1984:13). The speaker went beyond the immediate context (of formal speech rendered in a second language) to draw on a socio-cultural phenomenon that would enable him communicate 21 effectively. The hearers’ inference also has to depend on this whole gamut of nonimmediate context. The speaker got the expected reaction because the audience giggled at the mention of “Iya Alakara,’ an indication of the recognition of the speaker’s illocutionary intent. 3.3 Features Of The Radio Message Obviously, the evangelical Christian religions speeches delivered through the radio admit of a wider range of audience than the face-to-face interpersonal speeches: how does the speaker(s) then contrive the message(s) to suit the communicative situation? We want to examine the extent and types of mutual beliefs (MCBs) in the radio message. To avoid unnecessary duplication we shall only mention those features that are peculiar to the radio message: that is, we shall not mention the features shared by the radio message and face-to-face interpersonal message. 1. Arresting Audience Attention Encoders of the radio message spend the opening part of their speeches trying to appeal for decoders’ attention; and they (encoders) contrive to sustain this attention. In the speech titled “Armageddon’, the speaker spent more than ten minutes outlining why it was beneficial for the audience to hear him out. This was done through a sort of logical appeal. Let us sample some utterance for exemplification: i. It is a very important topic today and you cannot afford to miss it. (Information and Advisory). This utterance is one of the opening utterances of the speaker. The speaker, in an attempt to evaluate the topic of discourse, informs the audience and gives an assertive advice to the audience not to miss the discourse. The speaker has not revealed the topic before evaluating it. This serves to create suspense in the audience, thereby persuading hearers to listen to the message. The speaker acts on the belief that if the topic is important, then it must attract some attention from the audience. To further convince the audience, the speaker makes a ‘revelation” that ‘the Lord is unfolding mysteries to his own people’. He went on to assert that the topic is meant for the ‘children of light’ and ‘the children of the Kingdom’. While inferring the meaning of 22 this utterance, the audience may be faced with a number of questions: Who are the ‘children of light’ and ‘of the kingdom’? The audience will want to listen to the speech so that they may find answers to these questions. The lexical items have been carefully selected and are geared towards arresting the attention of the audience: ‘light ‘, in ‘the children of light’ has a socio-cultural significance, for it is almost instinctive that one would want to be associated with light and not darkness. Darkness is associated with the devil, which represents everything that is evil: while light stands for goodness, benevolence and everything positive. So, if the speaker says the message is meant for the children of light, the hearer will consider himself a child of light, and so will listen. ii. Many Christians, when they hear it (Armageddon), they shiver, they sake, they tremble, fear comes unto them (Informative). The speech act was uttered after the speaker had finally revealed the topic of discourse. The speaker was still evaluating the topic so as to solicit audience interest. The illocutionary force is that the topic is so important and mysterious that some Christians for fear whenever Armageddon is mentioned. The audience wanted to know why these Christians do fear and tremble, and the speaker did not leave them in much suspense; he said, ‘It is because of lack of understanding of that word’. A non –Christian member of the audience would wonder about the mysterious nature of the topic that even Christians don’t understand it. So as to understand, hearers will want to listen, more so when the speaker has even asserted that the Lord wanted to reveal the meaning of the word to any willing listener. A collection of verbs (shiver, shake, tremble and fear) is used to describe the feeling of some Christians whenever they hear the work, “Armageddon’. These verbs have been piled up so that the speaker would place the topic on a high pedestal. The audience also would see themselves shivering while listening to the report of the reaction of others; so as not to shiver for long, the audience would listen. Putting the audience in this helpless situation goes to validate another Christian belief that only through a ‘broken heart’ can the Lord Jesus enter in. 23 The speaker would not stop until he has specified the type of audience the message would benefit: iii. Once again, I want to reiterate that this message is going to benefit those Christians who want to grow in the Lord’ (Assertive). The speaker was making a claim here, and his intention was to make the audience know the type of Christians the message would benefit. He (the speaker) was acting on the belief that a normal person would want to grow and not remain in the same position. Since people need growth, and the message would supply the nourishment for this spiritual growth, then there is the need to listen to what the speaker would have to say. He went ahead to specify the type of growth he was referring to in “Those Christians who are hungry and thirsty after righteousness; those who are not satisfied with what they know about the word of God”. Here, the speaker was exploiting the inquisitive nature of man, the nature that will always want man to seek after knowledge. The audience would hear this and the inquisitive instinct would be aroused. If man continues to be swayed by lack of contentment and inquisitiveness, he will always seek for knowledge: iv. a) The mysteries of the kingdom, they are meant to be understood by the children of the kingdom (Assertive). b) My sister, my brother, you are a child of the kingdom, you are a child of God (Assertive). c) There should be no veil, no darkness in the understanding of the word of God to you (Assertive). d) And so is this message for you today (Assertive). e) And God, surely, will bless you in the name of Jesus Christ (Assertive). With these five speech acts the speaker assures his hearer that the message is meant for him. The speaker enrolled the audience in his group and assured the audience that they really belonged there. By forming this association with the audience, the speaker persuades the audience to listen. Through the piling up of Assertives, the audience would be certain and assured that the speaker really meant what he was saying. 24 The topic had earlier on been referred to as a mystery and the speaker has justified this by reporting the reaction of other Christians to the topic. So when ‘mystery’ is used in (a), the audience is expected to recognize the inter-speech act connection. This brings to mind the whole gamut of the Master Speech Act Adegbija (1982:125) mentions. He observed that the understanding of the whole utterance will depend on the recognition of the illocutionary force of the individual speech acts contained in a discourse. As the study has confirmed , all elements in a discourse are geared towards achieving a specific act and the audience would need to understand the elements before the speaker could be said to have achieved his intention . v. Be wise today, build your house upon him, he cannot fail (Advisory , Advisory and Assertive) (From Armageddon). With these three speech acts, the speaker finally ended his appeal for the audience’s attention. In the few preceding illocutionary acts, the speaker reiterated God’s intention: That the hearers’ knowledge is increased. The speaker refers to Proverbs chapter 24, verse3; where it is mentioned that through wisdom and understanding a house is built on a firm rock. The speaker asserts that this firm rock is Jesus Christ and wisdom is provided in the word of God. (Source: The Holy Bible) By inference, it would be understood that it is an act of wisdom to acquire God’s knowledge; that a life that has an orientation in God’s knowledge will stand firm in the storms of life; and, that success is sure if one builds his life on the firm rock (Jesus Christ) that cannot fail. Because of the socio-political reality shared by the interlocutors, the speaker felt the need to emphasize the firmness of the knowledge (of God) he wanted to expose to his audience. Some members of the audience might be looking for solace. Thus, the panacea presented by the speaker, through syllogism is expected to be appropriate to this type of audience’s needs. 25 3. Other Rhetorical Devices Apart from arresting audience’s attention, speakers employ some devices in the development of their messages. Among these features are the employment of a conversational tone and explicitness of presentation. a. Conversational tone: As regards the use of a conversational tone, two features are prominent: the use of a deliberative style and the supply of the feedback. i. The deliberative style refers to a device whereby speakers assume the style of debate and try to carry the audience along with as if they were engaging in a collective or joint business. It is a rhetorical device aimed at establishing rapport with the audience. It is one of the elements employed to help the speakers achieve their desired goal of persuasion. The pointer to his feature is the request introduced by ‘let us ‘as seen in the following examples: –Let us read it again. (from ‘Armageddon) -Let us go into the word of God. (“From the City of God”) -Let us go there together. (from ‘the City of God’) All these three utterances are Directives. The speakers want the assumed attentive and cooperative audience to peruse the specified portion in the Bible with them; the speakers try to emphasis this so that they would be conscious of the fact that some people were listening to them. The speakers see the need to create a face-to face interpersonal communicative mood, for it created an impression that he was not just talking to the air. The speakers have a conception of their audience and they ‘fashion’ their messages to suit their conception (of the audience). In other words, the examples have shown that the speakers’ conception of their invisible audience makes them to ‘Cooperate’ with the audience and contrive their speeches to meet the appropriateness conditions of discourse. ii. The second aspect of this conversational tone is the speakers’ efforts to supply feedbacks to their speeches. In a situation where the speaker is physically present, the audience can react to the speakers’ requests wherever necessary. In Christian religious speeches, such requests 26 are couched in utterances like ‘Praise the Lord’ and say ‘Amen to that’. Whenever such occasion arose, the speakers in this group of data would say “Hallelujah’ to his own (speaker’s) request of “Praise the Lord” and ‘Amen” to “Say amen to that”. The speaker has to substitute this personal reaction with the feedback he would have got if the audience were physically present. b. Explicit and Clear Presentation A major presupposition in force in a Christian religious message delivered through the electronic media is the (assumed) ignorance of the audience concerning the deep things of Christianity. Speakers refuse to take anything for granted. Because of this, speakers strive towards explicitness and clarity. In effect, some lexical items and some concepts that would have been taken for granted in a face-to-face interpersonal communicative environment were explained. Such items in ‘Armageddon ‘were: the spirituality of the Bible, the spirit of God, the tree of life, and the river of life. Let us take a look at the following utterances: i. The Bible is a spirit book to be understood only through the spirit of God (Assertive). The speaker is not only reporting but he is displaying a belief, a state of affairs, and inviting his audience in contemplating and responding to it. The illocutionary intent was to convince the audience that the Bible was a viable authority. Through this, the speaker was justifying his constant reference to the spirituality of the Bible, and then he would not be questioned by the audience fro taking it as the source of information. Contained in the utterance are two speech acts, and both are Assertives: – The Bible is a spirit book and the Bible can only be understood through the spirit of God. By association, this Assertive will help the audience to infer why the speaker has referred to the knowledge of the topic as the knowledge of God. That is, it is knowledge of God because the topic is taken from the spiritual book which can be understood only through the spirit of God. So the spirituality of the book has something to do with the spirit of God. 27 ii. He that has an ear let him hear what the spirit, the spirit is saying to the church (Requisitive). The speaker continues with his emphasis on the spirituality of the Bible and with the assertion that it is the spirit of the Bible and with the assertion that it is the spirit that explicates these mysterious things. Because the utterance also has an assertion, I don’t want to see it as just a request to listen. The assertive has the effect of emphasis of the need to listen. The speaker emphasizes ‘ear’ and ‘the spirit’. The lexical items have religious connotations which were explicated by the speaker. He said ‘ear’ does not refer to the spiritual things. He said it was the spirit and not any preacher or evangelist that was speaking. With the mention of the spirit as the speaker of the message, the speaker makes the audience to look beyond the limitations of mortal wisdom for the source of what the audience would learn from the topic of discourse. The other rhetorical devices identified in the previous section like repetition and emphasis through tonal variation, were also used here to clarify the speaker’s communicative intention. Speech making is an act and an art; the rhetorical features are the ornaments, the embellishments employed by speakers to sweeten and beautify their speeches. The rhetorical features are superimposed on the speech acts to affirm the illocutionary intention of the speakers. FINDINGS AND CONCLUSION Some of the major findings of this study are discussed in this section. a. Master Speech Acts and Constatives Mc Croskey (1968) observes that all messages in a rhetorical communication are meant to persuade the audience; and, Barret (1973:257) argues that every communication is a social act, and every social act is potentially persuasive. He argues further that persuasion is “the study of ways in which speakers affect the 28 thinking, feeling and behaviour of people”. The object of persuasion in the data analyzed is to influence the attitude of the audience towards the intended direction. The analysis done here has revealed that there is a directive force underlying religious speeches which serves as a binding wire to join all the individual speech acts together as recognized by Adegbija (1982: 125). The Master speech act makes the audience see the whole message as a single speech act and puts the perlocutionary effect of the message in a clear perspective. If one knows the overall intentions, it becomes easy to verify whether the intended effect is achieved or not. The analyses have shown that Constatives constitute 82% of the total speech acts in the analysed data. This indicates that Constatives are very important in religious communication. The special function of Constatives is corroborated by earlier studies in the field. Adegbija states that “The main function of Constatives is to provide felicity for the mapping of the sequences of speech acts performed in an advertisement into one master speech act, a process in which the general pragmasociolinguistic context of the ad and the reader’s world knowledge play a crucial role” (Adegbija, 1982: 126-127). This study reveals that speakers perform especially Informative and Assertive acts to convince the audience, thereby creating plausibility for the Advisory act the speakers were looking forward to performing at the end of the speech. Constatives also help the speaker to reiterate his point better – all geared towards influencing the belief(s) of the hearers. Mc Croskey’s observation mentioned earlier validates the above observation about Constatives: The speaker directed his religious message towards the attitudes and beliefs of the audience, so as to modify these towards an intended direction. This hypothesis has been convincingly confirmed by our analysis. All the rhetorical devices recognized in the speeches have been explained to be motivated by the speakers’ persuasive intention, and persuasion prepares the ground for the final advice given to the audience to join the speakers’ group (of Christians). 29 As noted earlier, a constative, in Bach and Harnish’s conception, is the expression of a belief, and the expression of an intention that the hearer forms (or continue to hold) a like belief (Bach and Harnish, 1979: 42). Precisely then, in Christian religions speeches, they (Constatives) are used in our data to tell the audience about the belief held by the speaker as shown by the following example: The only rock that is firm and stable is the rock that is the Lord Jesus Christ. Assertive (from Christian and Cults) This is a strong assertion. The illocutionary intent is that Jesus Christ is the only stable and firm rock. It is the master speech act because all the speech acts are intended to state this fact. The speech act presupposes that: i) A rock is very firm and stable. ii) There are many types of rock. (Basis: the use of ‘only’ and world knowledge) iii) That there is only one rock that is firm and stable (Basis: knowledge of the Bible). At this point, the audience will have to go beyond the literal level to infer the meaning of the speech act. For instance, the literal level will reveal that Jesus is not a rock. Consequently, the non-literal interpretation is applied to derive the meaning of the speech act, i.e. that the utterance is a figurative expression. The basis of the application of the non-literal level is the CP and the MCBS. The importance of the speech act is that it informs those who don’t known, and helps those who already know about this Rock to confirm their knowledge. In other words, Constatives do two or three things in Christian religious speeches: they inform the audience, they help confirm the belief of the audience and prepare the way for the master speech act. b. Perlocutionary Effects Adegbija (1982:180-183) convincingly argues that a perlocutionary effect, that is the effect the message has on the hearer, could result from ‘(a) the illocutionary act H understands S to be performing: (b) the propositional act H understands S to be performing and, (c) the thought H understands S to mean to express by P (the proposition). Adegbija also projects Davis’ argument that it is not sufficient to be 30 understand in performing an illocutionary act, “but what we want to bring about are certain effects, on the thoughts, actions and feelings of our hearers, for our purpose in bringing these about is the point or purpose of our communicating and the achieving of our purpose is the performance of a perlocutionary act” (Davies ). The foregoing argues, just as Bach and Harnish have conceded, that achieving illocutionary uptake and perlocutionary effect does not terminate if the hearer recognizes the illocutionary intent of the speaker, but if the hearer forms a corresponding attitude that the speaker intended him to form. This is the back-borne of Bach and Harnish’s taxonomy, and indeed of the entire theory. In Evangelical Christian Religious Speeches, two types of perlocutionary effects can be identified, and the two types have to do with the two broad types of audience we have identified with Christian religious communication, that is, the believers and the unbelievers. i. The speaker wants his message to achieve the effect of informing a believer, thereby increasing his audience’s (believers’) knowledge in God, and strengthening the believer’s belief in the Christian religion. For instance, in “Armageddon”, the speaker said the message would benefit those Christians who want to grow in the Lord; those Christians who are hungry and thirsty after righteousness …’ this comment, analysed earlier, is supposed to admit believers into the message. The speaker seems to presuppose that believers may not want to be attentive since they already ‘know’ about the Bible. Another example to show that speakers want believers to listen to them is the utterance “Many Christians when they hear it [Armageddon] they shiver, they shake, fear comes unto them”. The proposition of this Information act is that some Christians hear Armageddon and tremble because they don’t understand it, why don’t you (my hearer) listen so that you will understand and not tremble? Those of them who ‘tremble’ will hear the comment and decide to sit tight; and someone who doesn’t tremble will want to know whether there is more to Armageddon than he actually knows. 31 At the end of the message, the speaker will expect these believers to become informed and their belief will be consolidated. This is the first type of intended perlocutionary effect in religious speeches. ii. The perlocutionary effect of the speaker’s message on the unbelievers’ thoughts, feelings and belief(s) is the second type of intended effect to be identified. The speaker wants a change in the unbeliever’s belief and the master speech act is designed more to achieve this aim. This intention of the speaker is usually overtly stated in religious communication. There is usually a provision for the hearers’ reaction at the end of the message when the speaker would invite anybody who wants to decide for Christ, to come to the front. In most cases, especially when the interpersonal communicative situation is obtainable, many hearers do respond by standing up, raising up their hands, going to the pulpit, or in any other way stipulated by the speaker. Where we have this type of responses, we can say the message has secured ‘up-take’: the speaker has been understood by the hearer, and an effect has been produced. In most cases, this seems to be the ‘ultimate perlocutionary effect’ of the Christian religious communication message (Adegbija, 1982: 283). This effect is usually very immediate; it is immediate because the communication situation allows for it. There are, however, some cases when the audience will leave the immediate content of the message to go and ponder over the speaker’s invitation, and then end up having his belief modified, or even changed. It is pertinent to note, however, that this discussion does not assume that everybody who listens to a Christian religious message will show a perlocutionary effect of either (I) or (ii). There are cases when the effect would not be the one intended by the speaker. Some hearers make a mockery of the message, while others actually know more than what the speaker can say. These are perlocutionary effects all the same, only that they are not the intended effects. c. The Indirect Speech Act Adegbija (1982: 113), says one of the motivations for the use of the indirect speech acts, at least in consumer advertisements, is the need for the advertisers to 32 separate themselves from the message. This study, however, reveals that speakers try to create a rapport with the audience, and at the same time they identify themselves with their message. As a result, the use of the indirect speech act is unnecessary. Indirect speech acts are context dependent, for their comprehension relies on the mutual beliefs of the interlocutors. In essence, if the audience does not have a similar world knowledge with the speaker there may be communication breakdown. The audience of the Christian communication, especially the radio message, is varied. So as to avoid a communication gap, the speakers make a sparing use of the indirect speech act. The heavy dependence of the indirect speech act on the pragmasociolinguistic context is confirmed by Lyons (1977:784-784) and Adegbija (1982: 89). The dominant type of indirect speech act is the one analyzed earlier in this section: “The only rock that is firm and stable is the rock that is the Lord Jesus Christ.” We said the audience will have to go to the non-literal level to infer the meaning of the utterance. Even here, the speaker tries to clarify what he means so as to avoid misinterpretation. The indirect speech act has a negligible 2.8 percent of the data analysed in this study. CONCLUSION In conclusion, this study is important because it analyses religious speeches, and religion is an indispensable social phenomenon. The analysis shows us how language is used to mean in this important social phenomenon. The evangelical religious speaker has an intention which he wants the audience to recognize and respond to. Further studies are, however, required in communication to help us determine the amount and nature of the indirectness involved in our day-today social interaction. 33 THE TYPES AND PERCENTAGE OF SPEECH ACTS IN THE EVANGELICAL RELIGIOUS SPEECH ANALYSED DATA 1 2 3 Assertives 30 35 39 Predictives 1.0 2.4 1.0 Retrodictives 16 1.5 10 Descriptives 4.0 CONSTANTIVES 1.3 Ascriptives Informative 24 25.8 Confirmatives 4.6 1.6 25 Concessives 0.8 1.4 1 Retractives Disputatives Responsives 1.2 Suggesives 3.5 Supportives DIRECTIVES Requestives 3.8 Questions 2.0 Requirements Prohibitives 4.6 10 4.4 6.5 3.2 Permissives Advisories 3.6 3.0 1.2 COMMISIVES Promises 3.3 10 Offers 1 7 4 1 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Apologise Condole Congratulate Greet 0.8 0.5 100% 100% Thank Bid Accept Reject TOTAL KEY: 1: Christian and Cults; 2: Holiness Unto the Lord’; 3: Armageddon; 4. City of God 34 100% The break down of the speech act types shows that: Constatives: 82% Directives: 13.3% Commisives: 4.1% Acknowledgement 0.6% 1. ‘Christian and Cults’ has a total number of 250 speech acts. (40 mins) 2. “Holiness unto the Lord’ has 260 speech acts (40 mins) 3“Armageddon’ has 223 speech acts (35 mins) 4 The City of God has 201 speech acts (30 mins) The indirect speech act has a negligible 2.08 percent in all the four speeches. REFERENCES ADEGBIJA, E.E.., A Speech Act Analysis of consumer Advertisements. Ph.D. Dissertation, Bloomington: Indiana University,, 1982. “What is semantics in English as a second Language (ESL)?” Unpublished. Austin, J. L. How to Do things with Word. 2nd ed., ed. Jo Urmson and Marina Shisa, Cambbridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press .1962. Bach K. and Harnish, Robert M. Linguistic Communiction and Speech Acts . Massachussets: MIT Press, 1979. Bloomfield, L. Language. London: Allen and Unwin, 1935. 35 Lyons, John. Sematics 2 Vols., Cambruidge: London, 1977. Pratt, M. L. Towards A Speech Act Theory of Literary Discourse. London: Indian University Press, 1977. Searle, John. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language Cambridge University Press, 1969, p. 12 “Indirect Speech Acts”. Syntax and Semantics Vol. 111, Ed.P. Cole and J.L . Morgan. New York: Academic Press, 1975, 59 – 82. Traugott and Pratt, Linguisitcs for Students of Literatures New York: Harcourt Brace Javonovick, Inc., 1980. 36