Investigating sign language development, delay

advertisement

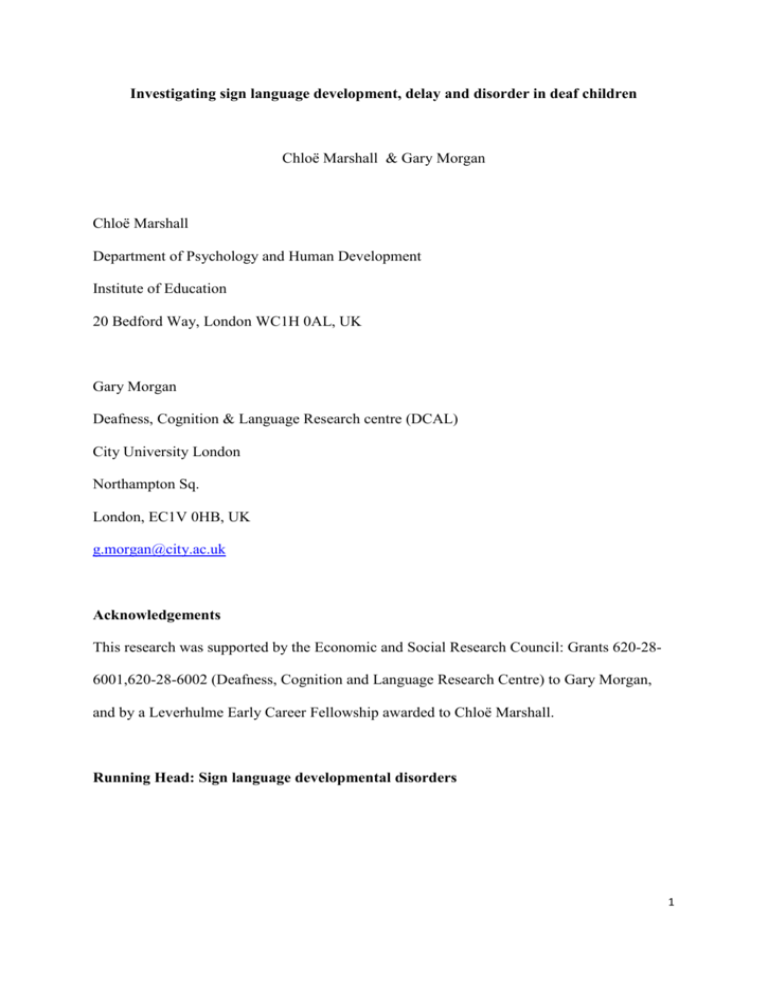

Investigating sign language development, delay and disorder in deaf children Chloë Marshall & Gary Morgan Chloë Marshall Department of Psychology and Human Development Institute of Education 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL, UK Gary Morgan Deafness, Cognition & Language Research centre (DCAL) City University London Northampton Sq. London, EC1V 0HB, UK g.morgan@city.ac.uk Acknowledgements This research was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council: Grants 620-286001,620-28-6002 (Deafness, Cognition and Language Research Centre) to Gary Morgan, and by a Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship awarded to Chloë Marshall. Running Head: Sign language developmental disorders 1 Abstract Around 7% of hearing children have a language learning disorder. In this chapter we explore whether a language disorder can also occur in deaf children who sign. One of the most researched areas in deaf children’s development is their acquisition of language. Native signers achieve predictable milestones during language development but represent a small group within the deaf child population. Many studies have found serious and long-lasting effects of early language deprivation on linguistic and communicative competence in deaf children with hearing parents. However there has been little attempt to tease apart whether these problems are caused by delayed exposure, a language learning disorder or both. Indeed, the distinction between delay and disorder is a very difficult one to make and is tied to how we assess children’s signing skills. This chapter reviews what we understand about sign language developmental disorders. As with the study of language impairment in hearing children, much of the devil is in the detail. Establishing a research methodology which can reliably separate out effects of natural variation, delay and disorder is all about who is in the research team and what tools are available for assessment. Notwithstanding these challenges, it is important that a deaf child’s language assessment can pinpoint what aspects of language need to be addressed so that any intervention is evidence based. Our studies indicate that the picture is a complex one, with both variation across children and differences between language disorder in the deaf and hearing populations. Key words: deafness, sign language, language disorder, specific language impairment, assessment 2 Many species communicate, but only humans have language. Language is universal across all cultures, and it is almost impossible to imagine how activities so central to our lives such as maintaining relationships, thinking and instructing others could happen without it. For example, current ideas about how children develop theory of mind stress the vital contribution of their language and communications skills (Pyers & Senghas, 2009; Meristo, Hjelmquist & Morgan, 2012). Language has been termed an “instinct”, an innate ability that is as specialised an adaptation as the spider’s web or the honeybee’s dance (Pinker, 1994). At the same time we also know that the language-making instinct is sensitive to the richness and type of input that the child receives (Hoff, 2006). Language development in children follows a predictable pattern. Children assemble their first phonemes in order to produce single words before they begin to combine those words into sentences. They produce content words (such as nouns and verbs) before function words (such as articles and prepositions) and construct short, grammatically simple sentences before longer sentences involving complex constructions such as relative clauses (Brooks & Kempe, 2012). The robustness of children’s language development is no more evident than in the context of children learning signed languages, where with native exposure they follow a similar pattern and achieve the major milestones at very similar ages to children learning spoken languages (see chapters in Morgan & Woll, 2002; Schick, Marschark & Spencer, 2006). There are individual differences in all aspects of cognitive development, and language development is no exception. Fenson and colleagues (1994) report that the average Englishspeaking child produces his or her first word around 10-12 months of age and by 16 months has a productive vocabulary of about 40 words. Nevertheless, individual children vary considerably, with children at the 90th percentile producing around 180 words at 16 months, whilst those at the 10th percentile produce only 10 words (Fenson et al, 1994). Similar 3 figures have been shown for Deaf children exposed to British Sign Language from birth (see Woolfe et al, 2010). Thus within the typical language-learning child population there is variation in rate and patterns. We are able to track this with precision in many spoken languages because normed tests of language development have been created. It is more challenging when the language being acquired does not have these normed tests or when children are exposed to more than one language at the same time, as is the case for the majority of young children in the world. At the same time there is developmental variability that goes beyond the bounds of what is expected. A small minority of children in all languages will fall below the natural bounds of language development. For example, van der Lely (1997) describes a case study of an English-speaking hearing child who at the age of 5 produced just three words. Thus normed tests also allow researchers and clinicians to pinpoint more serious and persistent language learning disorders. There are various reasons why a child’s language development might be thrown off its expected time-course. Those reasons can be external to the child, such as poor quality language input, or they can be internal to the child (Hoff, 2006; Reilly et al, 2010). This chapter focuses on an internal or organic reason, Specific Language Impairment (abbreviated to SLI). SLI is a developmental language disorder characterised by a delay in language development that cannot be explained by low general intelligence, a sensory impairment that would prevent language uptake, inadequate opportunity for acquiring language, or a known neurological cause such as traumatic brain injury or epilepsy (Bishop, 2014; Reilly et al, 2014). SLI is known to be genetic in origin, although the aetiology is complex and not yet well understood (Newbury, 2013). It can be diagnosed as young as the preschool years (Reilly et al, 2010), and whilst for some children it will resolve, for others it will persist into adulthood (Tomblin et al, 1992). 4 SLI has been researched in a large number of typologically diverse spoken languages, including Cantonese (Stokes et al, 2006), English (Tomblin et al, 1997), French (Thordadottir & Namazi, 2007), Gulf Arabic (Shaalan, 2010), Hebrew (Friedmann & Novogrodsky, 2004), Russian (Tribushinina & Dubinkina, 2012), Swedish (Hansson, Nettelbladt & Leonard, 2000) and Turkish (Rothweiler, Chilla & Babur, 2010). Recently there has been a growth in interest and work on SLI in bilingual children (Armon-Lotem, 2010; Paradis, 2010). SLI has been much less researched in signed languages, but several studies in British Sign Language (BSL) have been published in the last 10 years, and the aim of this chapter is to summarise their findings and to set out a description of what methods and personnel are needed for this enterprise. This is an interesting topic both theoretically and practically. Understanding both the universal and modality-specific characteristics of SLI will enable us to understand more about the disorder in general. In practical terms it is crucial that professionals working with deaf children are able to identify cases of SLI, particularly in the challenging contexts of late language exposure. The plan of the chapter is as follows. We begin by reviewing some of the linguistic features of SLI across different languages. We then discuss issues involved in identifying and researching SLI in the deaf signing population, which includes details about methods, testers and analysis. The bulk of the chapter is given over to reviewing a set of studies of SLI in deaf signers who use BSL, and a comparison of the profile of sign SLI to that of hearing children with SLI in spoken languages. We conclude by setting out a roadmap for future research on SLI in signed languages. 5 <1> SLI: diagnosis and cross-linguistic characteristics Diagnosing SLI in any child is not straightforward (Williams & Lind, 2013). SLI is unlike Down Syndrome, Williams Syndrome or Velocardiofacial Syndrome, for which the genetic bases are well understood and where simple and accurate genetic tests exist for diagnosis. Instead, SLI is like Developmental Dyslexia, Autism Spectrum Disorder, and Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), which are behaviourally defined. A diagnosis of SLI relies principally on assessing children’s performance on standardised tests of language. However, this is more complicated than it might sound. Language abilities occur on a spectrum, meaning that decisions have to be made as to where the cut-off between typical and atypical performance lies, and such decisions have a degree of arbitrariness (Reilly et al, 2014). Decisions also have to be made as to which aspects of language are assessed: should both language comprehension and language production be measured, and which of syntax, morphology, vocabulary, pragmatics and phonology should carry most weight in the assessment process (Dockrell & Marshall, in press)? All of these issues are very relevant for studying SLI in deaf children’s sign language development as well. The inclusion of “specific” in the term SLI is designed to indicate that this is an impairment solely of language, or at least that the child has marked weaknesses in language in comparison to non-language abilities .With respect to diagnosis, this means that alongside the criterion that language is impaired, there are also various exclusionary criteria. SLI cannot be diagnosed when the child has low non-verbal abilities because these might conceivably affect the child’s language-learning abilities. Like language, however, non-verbal ability occurs on a spectrum, meaning again that rather arbitrary decisions have to be made as to what counts as “low”. SLI is frequently co-morbid with other developmental disorders, meaning that children who have it are at increased risk of also having, for example, reading difficulties (dyslexia and/or poor reading comprehension) and ADHD (Reilly et al, 2014). 6 Language impairment is also a common feature of autism. Such co-morbidity challenges the notion of an impairment that is ‘specific’ to language and is the subject of massive debate in the literature. How specific to language SLI actually is, becomes relevant when working with deaf children who might have a suspected developmental disorder. The complexities of diagnosis mean that even in hearing monolingual children there is considerable debate about the exact criteria for a diagnosis of SLI, about whether those criteria identify a homogeneous and coherent group of children, and even whether the term ‘SLI’ has scientific, clinical or educational validityi (Reilly et al, 2014). Nevertheless, it is critical that children with low language levels are identified so that they can be offered support from clinical and educational services. Different diagnostic criteria will, of course, capture different proportions of children within their net, but estimates that SLI affects approximately 7% of children at the age where they would start school (Tomblin et al, 1997) are widely accepted. The children who receive a diagnosis of SLI form a heterogeneous group with respect to the severity and profile of the disorder (Leonard, 1988). One of the goals of SLI research has been to uncover “clinical markers”, i.e. language characteristics that the vast majority of individuals with SLI share, that persist even in individuals whose overt language difficulties appear to have resolved, and which are heritable (Bishop, 2006). Three clinical markers have been proposed for English-speaking children: omission of tense morphemes (saying, for example, “Yesterday I walk” instead of “Yesterday I walked”, hence omitting the -ed suffix; Rice & Wexler, 1996), inaccurate repetition of non-words (e.g. perplisteronk, a made-up word which most children with typically developing language will repeat accurately the first time they hear it, but which children with SLI are unlikely to be able to do; Bishop, North & Donlan, 1996), and inaccurate repetition of sentences (Conti-Ramsden, Botting & Faragher, 2001). 7 Cross-linguistic research on SLI is valuable because it allows researchers to investigate whether such clinical markers are relevant just for English or whether they are the same for other languages too. In much of our own work on sign language SLI we have followed this idea of identifying clinical markers based on spoken language research, and have investigated whether these might be different in a signed language compared to a spoken language. Different languages afford the possibility of different types of errors in acquisition. For example, Chinese has no tense marking, so Chinese-speaking children with SLI do not have the opportunity to make tense-marking errors. However, Chinese, in contrast to English, is a tonal language. Might Chinese-speaking children make errors in their choice of tone for words? Such comparative research is important because it allows us to look beneath the surface characteristics of the language and gain insight into what is more fundamental to the disorder, thereby gaining insight into what the underlying causes of the disorder might be. Cross-linguistic studies reveal that problems with inflectional morphology (and not just tense marking) are characteristic of SLI in many languages, including Dutch, German, Italian, and French (Crago, Paradis & Menn, 2008). Non-word repetition is also problematic across a range of languages, including Dutch, Spanish and Swedish (de Bree, Rispens, & Gerrits, 2007; Girbau & Schwartz, 2007; Kalnak et al, 2014). Several syntactic constructions have also been found to pose problems for children with SLI in numerous languages, including wh-questions (i.e. questions with ‘who’ ‘which’, or ‘what’, Schulz & Friedmann, 2011) relative clauses (i.e. the underlined portion of the girl who lives next door; Friedmann & Novogrodsky, 2004) and passive sentences (i.e. ‘the dog was chased by the cat’; van der Lely & Harris, 1990). The picture of SLI that emerges from such cross-linguistic research, therefore, is of a disorder that principally affects syntax, morphosyntax and phonology, and in which 8 vocabulary and pragmatic impairments may be present in some children but are less severe (Leonard, 1998; Rice, 2013; van der Lely, 1997). Is this the same profile that we see in deaf children acquiring sign languages? <1> Studying deaf children with SLI Our understanding of sign SLI is growing (for British Sign Language - BSL: Morgan, Herman & Woll, 2007; Mason et al., 2010; Marshall et al., 2013; Marshall et al., in press; Herman et al., 2104; and for American Sign Language – ASL: Quinto-Pozos, Forber-Pratt and Singleton, 2011). Several years prior to setting up our own systematic study of SLI in signing children, there were two areas of work that were very informative. Firstly, some of our colleagues were documenting the existence of atypical sign language use in both children and adults with developmental and acquired disorders. While these individuals had difficulties in wider cognitive skills as well as language, they did give us a good grounding in how to study this topic. Amongst these studies were reports of children with Down syndrome (Woll & Grove, 1996) and deaf adults with aphasia (e.g. Atkinson, et al, 2005; Marshall et al, 2004). This early groundwork suggested to us that it was possible to study atypical sign language and to compare atypical sign language users with hearing populations with similar profiles (for an overview of this work, see Woll & Morgan, 2012). Secondly, our colleagues in speech and language pathology practice were informing us regularly of children whom they believed had SLI in their signing. Through our interaction with speech and language therapists working with deaf children it became obvious to us that children with language impairments above and beyond the expected range of language variation were being identified and evaluated in clinics. Indeed, even children with native or high quality sign language exposure early in development were being referred for assessments. Thus we had developed some expertise in working with atypical signers and 9 there was a growing awareness that sign SLI might be a real disorder. In order to find systematic evidence of sign SLI, however, there were several factors to deal with. These were: 1. Late exposure to sign language is the norm for deaf children. 2. Few standardised sign language assessments are available. 3. The skills required from testers to identify sign SLI are very specialized and come from multiple disciplines. 4. There is an incomplete understanding of the adult sign language system (i.e. the target) with which to compare children’s development. In the following section we expand on each of these in turn. <2> Late exposure to sign language The main stumbling block for studying the differences between delay and disorder in deaf children is that the vast majority (90-95%) of deaf children who are exposed to a sign language are born to hearing non-signing parents. This means that even in cases where hearing parents learn BSL and sign with their children from an early age there will be question marks over the quality and quantity of exposure to sign. We do not know how much exposure to sign is necessary for typical development or whether primary language exposure can come from adult non-native learners, and in general it is not completely clear what ages are the most critical or sensitive for different aspects of sign language phonology and grammar (Ferjan Ramirez, Lieberman & Mayberry, 2013; Morgan, 2014; Schick, 2004). In sum, from the outset of studying sign language SLI it is important that one understands the complexities of the population. The typical situation for a deaf child who learns a sign language is late exposure to a less than optimal input. This means that if a child displays a 10 language delay, it is challenging to determine whether this is because of the late exposure (an external factor) or because of SLI (a factor internal to the child). In a wider context, disentangling language impairment from language delay is also a challenge when studying hearing children who are exposed to two spoken languages at different rates. Not all bilingual children have balanced exposure to both languages at all stages of their development. While there is a general consensus that bilingualism in children does not cause permanent language delays (Genesee, Paradis & Crago, 2004), some bilingual children do have reduced input of one language temporarily during early language acquisition, which slows down acquisition of that language. A proportion of such children also have SLI, but it is difficult to diagnose SLI in children with uneven bilingual exposure (Paradis, Schenider, & Sorenson Duncan, 2013; Bedore & Peña, 2008). With respect to sign SLI, the best way to minimise the issue of impoverished input is to look for SLI only in native signers. This was confirmed in an early case study of a native signer who had very marked BSL delay (Morgan et al., 2007). Because this child had deaf signing parents, his delayed language development could not be explained by late or inadequate exposure to BSL. However, native signers make up a very small proportion of the signing child population. It is not possible to exclude from studies of SLI deaf children who have hearing parents, as this strategy would rule out 90% or more of the population. <2> Paucity of standardised sign language assessments In the wider SLI literature, diagnosis and profiling of cases of SLI relies on the use of standardised assessments of language, both omnibus tests and tests of more specific components of language such as syntax or vocabulary. In our sign SLI work we have used standardised measures to eliminate children with low non-verbal cognitive abilities or impaired motor difficulties that might contribute to their communication difficulties (see 11 Mason et al., 2010). In addition we used two standardised measures of BSL to confirm that the children’s language development was significantly below that expected for their age i.e. beyond natural variation. However, sign language tests are currently fairly limited with respect to which aspects of the language can be tested, compared to what is available for English. Worldwide, very few standardised measures of sign language exist because of difficulties obtaining a sufficiently large sample given the size and nature of the deaf population, and also because of the limited research on sign language and sign language acquisition in many countries (Mann & Haug, 2014). The exact same issue is present in studying SLI in many spoken languages, for which no assessment tests are available. We were fortunate in having two available measures (Receptive Grammar: Herman, Holmes & Woll, 1999; Narrative production: Herman et al., 2004). For each, the standardisation was based on a sample comprising deaf and hearing native signers, deaf children in hearing families on bilingual (BSL/English) educational programmes, and deaf children in hearing families on Total Communication programmes (using a range of communication approaches including BSL and English-based sign systems). Since the standardisation sample comprises, in the main, deaf children in optimal language learning environments, performance on these tests was used as an initial and only preliminary guideline. In subsequent testing of more specific aspects of signing, when we developed new language tests but did not have access to a standardisation sample, children’s scores were compared with those of children from the same schools. Both sets of children entered signing environments at similar ages and came from comparable home language learning backgrounds. This last point is important, because children with suspected SLI should be compared on tests with children with the same background language histories and quality of 12 input. Furthermore, we are currently adapting the BSL narrative production test to spoken English as in our recent studies many deaf children chose to narrate the story in English. <2> Range of skills required from testers and researchers It is important to stress that the systematic evaluation of language disorder in deaf children in our work was made possible by two main factors: 1) A team of native Deaf and hearing sign bilingual researchers, working closely with psychologists, linguists and clinicians with skills in sign language linguistics, language and cognitive assessments, and 2) the team’s knowledge of language acquisition in deaf and hearing populations. These areas of expertise and skill were necessary at all stages in the identification of SLI in deaf signing children, but we are aware that many professionals working with deaf children are not fluent signers or do not have a strong background in SLI and language assessment. In this latter scenario it is advisable a child with a suspected SLI in sign language be assessed by trained specialists through a referral service. However, it is often the case that referral to specialist services will not be possible. Many cases where a deaf child has been identified with slower than expected language development have been because of the gut instinct of the child’s parents, teacher or language specialist. This was often the case in our initial work, where language pathologists working with deaf children who signed informed us about children with severe sign learning delays. Nevertheless we had to attempt a systematic evaluation of children using whatever resources were available to us. If standardised assessments are not available, we advise a methodology for differentiating delay and disorder based on comparing the suspected SLI case with children who have received similar quantity and quality of exposure to a sign language on some form of language measure (see Mann, this volume). <2> An incomplete understanding of the adult sign language system 13 While no fully comprehensive linguistic analysis of any language has yet been completed, this situation is more exaggerated for sign languages, where there are great gaps in our knowledge and much disagreement. For example classifiers employ a particular handshape to pick out a class of nouns (e.g. flat objects) and can be used to describe a whole sentence e.g. ‘the book is under the bed’. However there is a profound lack of consensus in the research on classifiers in sign languages, with linguists disagreeing as to whether they are polymorphemic or not morphological at all (see Emmorey, 2003; Morgan & Woll, 2007). This lack of clarity as to how to describe different parts of the grammar extends to the status of pronouns, verb agreement (inflectional morphology) and even to phonology. This means it is difficult to know how to best conceptualise different language structures and to know what to expect of their acquisition in deaf children who sign, and this also slows down psycholinguistic work on the language. More generally, confusion arises when distinguishing signs from communicative gestures even in linguistic descriptions of adult native signers. The role of gesture in a grammar of a sign language is crucial for studying SLI. Describing linguistic skills can be especially difficult in children with limited signing who are adept at using the visual modality creatively to communicate. For example, if a deaf child uses mime, how is this different to what linguists call ‘constructed action’ (Quinto-Pozos, 2007)? In the first SLI case we reported (Morgan, et al, 2007), we observed that Paul used exaggerated gestures and facial expressions in spontaneous interaction. We argued this was a strategy to compensate for his poor linguistic competence, making his impairments less noticeable. He often used pointing to pictures, to himself and to others in lieu of full sentence structures. In addition Paul used more affective facial expression instead of the specific face and head linguistic markers, for questions, negations or manner modifications with verbs (for a recent example of this face strategy in deaf children with autism, see Denmark, et al, 2014). 14 With these four factors outlined, we hope to have highlighted issues that we dealt with during the evolution of our research studies. We suggest it is important to be aware of these four factors before embarking on the study of sign SLI. With this background complete, the next section outlines findings from a series of studies on groups of signing children who have SLI. Some children appeared in several studies allowing us to begin to develop profiles of impairment. Our aim in this chapter is to compare what we have found in BSL with what is known for these same linguistic domains in spoken languages. <1> Phonological skills The first component of sign language that we discuss here is phonology. Phonology is the level of linguistic organisation below the morpheme or word, and which organises the medium through which language is transmitted: be that vocal/auditory in the case of spoken languages or manual/visual in the case of signed languages. In signed languages, the units of organisation are generally considered to be handshape (i.e. the configuration of the hand), orientation, location, movement, and non-manual features (Brentari, 1998; Stokoe, 1960/2005). As we explained earlier, a marked difficulty in repeating non-words (i.e. spoken forms that follow the phonotactics of a particular language but have no meaning) is a robust feature of SLI in many languages (de Bree, Rispens, & Gerrits, 2007; Gathercole & Baddeley, 1990; Girbau & Schwartz, 2007; Kalnak et al, 2014).). Repetition is particularly difficult when the non-word is phonologically complex and contains phonological structures that are late-acquired, for example, consonant clusters and/or unusual stress patterns (Bishop, North & Donlan, 1996; Gallon, Harris & van der Lely, 2007) We investigated the manual phonological abilities in deaf signing children with and without SLI, using a test of non-sign repetition with non-signs at different levels of complexity (Mann, Marshall, Mason & Morgan, 2010; Marshall, Denmark & Morgan, 2006; 15 Mason et al., 2010). Non-signs are manual forms that fit the requirements for being signs but are not known as existing signs in BSL. There are not exact parallels between phonological complexity in spoken and signed languages but our non-signs differed in whether they contained an unmarked or a marked handshape (markedness can be defined as a sign which is more difficult to articulate and perceptually complex and is predicted to be more difficult to repeat). They also differed in whether they had a single movement (either path or internal movement) or a movement cluster (i.e. path plus internal movement, which again is predicted to be more difficult to repeat). An example of a BSL non-sign with a marked handshape but a single movement is shown across the two stills in figure 1. ----------------INSERT FIGURE ONE HERE------------------ The non-sign repetition test has norms derived from 91 deaf children ages 4-11 years (see Mann et al., 2010 for more details). In Morgan et al.’s (2007) case study of a native signer, the subject, whom we called Paul, performed extremely poorly on the non-sign repetition test (see Woll & Morgan, 2012). We tested a group of deaf signers with suspected SLI on the same test in Mason et al., (2010) to see if poor non-sign repetition could be a clinical marker for sign SLI (using the process outlined in section 2 previously). Of the 13 children tested only 5 demonstrated impaired non-sign repetition, where “impaired” performance was defined as a score lower than one standard deviation below the mean. Thus it appears that repeating non-signs is a weak skill in only a subset of our sample of sign language users with SLI, as opposed to being a clinical marker as has been reported for spoken language SLI. At first glance, the performance of our group of SLI children on the non-sign repetition task, on which the majority performed comparably to typically developing deaf controls, might appear to challenge the hypothesis that SLI is caused by a phonological 16 short term memory deficit (Gathercole and Baddeley, 1990). However, as we have argued elsewhere (Marshall et al., 2011), the repetition of non-signs appears to be a difficult task even for typically developing deaf children. Our explanation for this difficulty is that the phonological content of a non-sign is less predictable than the phonological content of a spoken non-word, and therefore its retention in short term memory is more cognitively costly. The basic idea here is that signs in BSL may have fewer limiting constraints than spoken language words with respect to how their sub-lexical components can be combined. In a sense there are more degrees of freedom for how sub-components combine in a sign than a word and this makes processing demands higher (Marshall et al., 2011). A developmental impairment in processing at the phonological structure of a sign might lead to impairments at several levels of the language, with one consequence being on the acquisition of new signs and the construction of the lexicon. If a child does not lay down good phonological representations, then building up a lexicon will be more difficult and accessing that lexicon in different contexts will be compromised. This leads us onto studies of lexical skills in children with SLI. <1>Vocabulary and semantic fluency In studies of spoken language SLI, profiles of impairment are heterogeneous, for example more children have impairments in expressive vocabulary than in receptive vocabulary, although not all children with SLI have vocabulary difficulties. Nevertheless, impaired vocabulary acquisition and word production are found in some children with SLI (Marshall, 2014). We were initially surprised to find that the native signer with SLI reported in Morgan et al (2007) had relatively unimpaired vocabulary. We assessed Paul’s receptive vocabulary using a non-standardized BSL version of the British Picture Vocabulary Scale (Dunn et al. 1982). His receptive BSL vocabulary was normal for his age, when compared to norms 17 collected from groups of normally developing signing children. We decided to look at vocabulary knowledge in other ways by developing a semantic fluency test for BSL. Research on hearing children with SLI has investigated the speed and accuracy of their lexical access skills using fluency tasks (Henry, Messer & Nash, 2012; Messer & Dockrell, 2013). In a semantic fluency task, participants are asked to produce as many words as they can from a specific semantic category, such as ‘animals’ or ‘food’ within a limited time period, most usually one minute. The test gives an indication of children’s semantic organisation: if they are able to generate exemplars in response to a superordinate label, e.g. ‘animals’ or ‘food’, then this suggests that their semantic knowledge is organized taxonomically. Furthermore, they often generate words in bursts of semantically related clusters of items, for example “cat, dog, rabbit, cow, horse, sheep, hen, duck…” (in this example, a cluster of pets followed by a cluster of farm animals), which suggests that semantically-related words are stored close together in the lexicon. In hearing children with SLI, there is evidence that at least some children generate fewer words during the course of the minute than their chronological age matched peers, suggesting a difficulty accessing either the phonology or the semantics of the word, or both (Henry et al, 2012; Messer & Dockrell, 2013). We used the semantic fluency task in BSL, with the categories “food” and “animals” as these are amongst the most commonly used categories in the spoken language literature. We tested 22 typically developing deaf signing children, aged 4 years to 15 years, and a group of 13 deaf signers with SLI, aged 7-14. Our findings indicated no differences between the SLI group and a subgroup of age-matched typically developing deaf signers in terms of overall numbers or types of responses (Marshall et al., 2013). This mirrors what we found with Paul’s receptive vocabulary. However, subtle differences were observed: the SLI group 18 produced fewer signs in the first 15 seconds than their typically developing peers and there was also some evidence of word-finding difficulties in the SLI group, suggesting that their access to signs was slower and less accurate. For example, a 14-year-old child signed MOUSE IN WHEEL – YOU KNOW and 7 seconds later retrieved HAMSTER. Another 14year-old created many compound signs, some of which were real items (DOGFISH, CATFISH, GOLDFISH), but others were not (REDBERRY, SEABIRD). A third child, aged 9, signed ORANGE BUT NOT HORSE, and never found the correct sign for the animal she was searching for. Our conclusion is that the deaf children with SLI who participated in this study did not differ from those without SLI in terms of the semantic organization of the BSL lexicon (at least, the limited part of the lexicon that we investigated), but that they accessed signs less efficiently. It is not clear from our data whether this is due to slower access to the semantic component of the sign, or to less efficient mapping from the semantic to the phonological form, meaning that the phonological form of the sign is retrieved more slowly or not at all. This matter is also subject to debate in the spoken language literature (Marshall, 2014). <1> Syntax and morphology One major area of language difficulty in hearing children with SLI is in their understanding and use of grammar. Indeed, the areas of syntax and inflectional morphology (i.e. the use of morphology on verbs to mark person and tense information e.g. third person singular ‘s’ and past tense marker ‘ed’) have been the most widely-studied in the SLI literature. Studies consistently report that hearing children with SLI have impairments in syntax and inflectional morphology that are more severe than their impairments in other components of language such as vocabulary. This means that not only do children with SLI score lower than their chronological age-matched controls on tests of syntax and morphology, but they also score 19 lower than younger typically developing children matched for scores on a vocabulary test (for a review, see Leonard, 1998). As we discussed earlier, the sorts of syntactic constructions that pose problems for children with SLI include wh-questions, relative clauses and passive sentences (Schulz & Friedmann, 2011; Friedmann & Novogrodsky, 2004; van der Lely & Harris, 1990). In English, the omission of the past-tense morpheme –ed is common in SLI. All these constructions have in common the features of being grammatically complex and acquired relatively late by typically developing children. Impairments are consistently found across a variety of measures, including comprehension tasks and production tasks such as sentence repetition and narrative elicitation. In Morgan et al. (2007) we reported that Paul’s comprehension of BSL grammar was 1.3 standard deviations below the mean compared with the standardised scores for children of his age. In addition, his performance was atypical or of a different quality to other signers, with success on some difficult items and failure on many easier ones. His performance could not be characterized as that of a younger learner, as by failing early items and passing more difficult ones his performance actually appeared random. Analysis of Paul’s sentence production in a conversation sample and elicited picture descriptions revealed that his expressive BSL was restricted to small sentences made up of one or two signs with very limited grammar. Despite this, Paul clearly enjoyed communicating and provided a range of appropriate affective (but non-linguistic) facial expressions and gestures. This supported our assessment that he was not autistic. Here we show examples of Paul’s descriptions from the picture tasks to an adult Deaf native signer, compared with similar age typically developing deaf children. Target picture: a dog in a box. 20 Paul: DOG whole body gesture with hands on the head (top of box) Adult: DOG WHERE? P: whole body gesture to show looking up A: PICTURE WHAT? P: BOX A: AND? C: DOG A: DOG WHERE? P: looks away and changes topic Typically developing native signer aged 4;6: C: POINT (picture) CL-(cube)-CL-(small animal)-SIT-IN-BOX English Translation: ‘there, the dog is in the box’ Target picture: a man giving a boy a letter. Paul: GIVE GIVE SQUARE GIVE (citation forms) A: SQUARE GIVE WHO? C: GIVE GIVE POINT (picture) LETTER A: PICTURE WHAT? C: LETTER POINT Typically developing native signer aged 4;6: C: MAN LETTER GIVE-3rd person agreement English Translation: ‘the man gives the letter to (him/her)’ 21 Sentence repetition requires the child to repeat back a sentence as accurately as they can as soon as they have heard it spoken by the assessor, and it has been used across a range of spoken languages. In a later group study of children with sign SLI we reported impaired performance on morpho-syntactic aspects of BSL by using a sentence repetition paradigm (Marshall et al., 2014). The child BSL sentence repetition test required children to repeat 20 signed sentences (including 3 practice items). Marshall et al. (2014) reported across the board impairments for 11 deaf children of hearing parents aged 7;4-12;9 with sign SLI compared with age-matched non-impaired controls. The stimuli to be repeated by children were presented on a video and consisted of 20 sentences with differing degrees of complexity attuned to the language agerange of the participants. Significant group differences were found for each linguistic element coded for: lexical content, spatial morphology, sign order, sentence meaning and facial expression. Previous work using sentence repetition in spoken languages has emphasised that verb morphology is difficult for children with SLI. We therefore looked in more detail at this component of BSL grammar. On the sign test the highest score for repeating sentences that included classifiers and agreement verb morphology was 9. There was a significant difference between the SLI group’s mean (4.27 points) and the control group’s (6.00 points). See Marshall et al. (2014) for more details. <1>Narrative The highest level of language organisation we investigated in sign SLI is narrative production. In contrast to conventional language tests, which elicit production and test comprehension using artificial tasks, narrative tasks provide a more naturalistic setting to examine children’s language skills (Dockrell & Marshall, in press). Because of the challenges posed to young children in constructing a coherent narrative, these tasks have been used to 22 investigate patterns of SLI in spoken languages (e.g. Botting, 2002; Wetherell, Botting & Conti-Ramsden, 2007). English speaking children and adolescents with SLI have been reported to produce narratives similar to those of younger typically developing children (Merritt & Liles, 1987; Wetherell et al., 2007). For example, Marini, Tavano and Fabbro (2008) found that they produced narratives with less developed sentence structure and use of verb morphology, and that they had problems with the anaphoric use of pronouns. In Morgan, et al (2007), Paul’s performance on the BSL Narrative Production Test (Herman et al, 2004) was at the 25th centile for all criteria (grammar and story structure elements). When we separated the grammar and story structure scores (introducing the characters, building up to a climax, providing a story coda, etc.) he scored higher in these elements (22/34 - 65%) than in his BSL grammar (9/30 - 30%). Thus it might have been the case that children with sign SLI are less weak in pragmatic aspects of language particularly in narrative. However in a recent larger study of sign SLI we in fact did not confirm this earlier prediction. Herman et al (2014) investigated the narrative skills of a group of 17 deaf children with sign SLI with a mean age of 10 years (range = 5;00–14;8). All children were from hearing parents and had been exposed to BSL before age of 5 (mean years of exposure = 6;6, range = 3;8–9;0). This group was compared with a control group of 17 deaf child signers matched for age, gender, education, quantity, and quality of language exposure and non-verbal intelligence. Children were asked to generate a narrative based on events in a language free video (the BSL production test – Herman, et al, 2004). Narratives were analysed for global structure, information content and local level grammatical devices, especially verb morphology. The language-impaired group produced shorter narratives (mean 26 clauses) than the non-impaired signers (mean 45 clauses). There were also significant differences in the 23 structural quality of the narratives between groups. For example at the start of the story good narrators set the scene (identify the main participants and objects). We see this in a sample from a 12 year in the control group. CL refers to classifier signs, LOC are specific locations in sign space: GIRL WALK-CARRY-TRAY (body movement indicating walking, using CL-HOLD-TRAY at the same time) ROLE SHIFT OH THERE (point to location of table) PUT-DOWN-TRAY (CL-HOLD-TRAY) ON TABLE HMM (strokes chin) WHICH FOOD BOWL (LOC-1) LOTS SWEETS LOC-2 (CLPLATE) SANDWICH LOC-3 (CL-PLATE) CAKE “So the girl carries in a tray of food and places it on a table nearby. She thinks to herself ‘which bowl should I fill with sweets?’ She puts the bowl over there, the plate of sandwiches here and the cake next to it”. In contrast we do not see this scene setting or clarity in the next example from a similar part of the story recounted by a 12 year old child in the SLI group: WALK (the handshape used is unclear as the child uses two hands instead of one) SIT SIT (different locations to show two people) BOY LAZY HANDS-TOGETHERLEAN-HEAD-ON-SOFA (use of gesture to describe boy’s actions) WATCH-TV (unclear handshapes) HE DEMAND DEMAND (unclear articulation which looks like the sign DON’T-KNOW) GIRL WALK “Comes in and they sit, the boy is sat lazily with his head back watching TV. He keeps asking for things and the girl goes over there”. In all the aspects of the BSL narrative components, SLI children were worse than controls i.e. semantic content, grammar including use of classifiers and role-shift (see Herman et al, 2014 for more details). Lastly in terms of pragmatic inferences we also found that the SLI children were worse at demonstrating an understanding of the motives of the characters in their own stories. We tested this by asking children to answer questions about 24 their stories which required some inference making. For example, the last question on the test is: ‘Why did the girl tease the boy’? The answer to this question is not supplied in the video stimuli but instead requires some perspective taking abilities and touches on Theory of Mind. A correct response would be ‘She wanted to surprise him’ and an incorrect one would be something like ‘The girl was naughty’ which only gives superficial information on motivations of the characters. Scores for answering these questions, where the maximum level is 6 points, were: SLI group mean 1.73 points and control children: mean 3.25 points. Similar difficulties in inference making have been reported for children with SLI in spoken languages (e.g. Norbury & Bishop, 2003). <1>Conclusions In this chapter we have detailed the growing evidence that sign SLI exists. In fact from our group study we estimated a prevalence rate for SLI in BSL of 6.4% (Mason et al., 2010). This is similar to the prevalence rates reported by Tomblin et al. (1997) for the hearing population. As we stated in the introduction, understanding both the universal and modalityspecific characteristics of SLI will enable us to understand more about the disorder in general: explanations of SLI must be able to account for both the spoken and signed modalities. The existence of SLI in a signed language, as we have argued elsewhere (Mason et al., 2010), is problematic for theories of SLI that claim that children with SLI have language impairments because they cannot process the rapid temporal changes in speech as efficiently as their non-language-impaired peers. The visual system does not have the same temporal resolution as the auditory system. Finding SLI in a signed language does not, of course, prove that temporal processing deficits do not cause SLI in hearing children, but it provides support for the view that at least some cases of SLI have an underlying cause that is not tied to one modality. 25 As we also stated at the outset, the study of sign SLI has revealed a complex and interesting picture of the disorder. Further, in some aspects of sign we see parallel levels of breakdown across modalities (verb morphology and syntax) while in other aspects we see no such consensus (phonological processing). We have argued this is characteristic of the typological differences across BSL and some spoken languages e.g. phonology might be organized differently in BSL than it is in English making different demands on the processing of the stimuli between modalities. Finally studying this disorder is also complex because of a set of issues related to the language, the child, the testers and the tests. When studying spoken languages, a lot is generally known about the adult target and typical child language development, and the path for attaining the adult target, the degree of variability, ages of acquisition of different words, grammatical morphemes and syntactic structures, etc, are known. For many spoken languages (although by no means all) a large number and variety of language assessments are available (Dockrell & Marshall, in press). This is rarely the case for signed languages. This means that a multi-faceted approach – experimental studies in psycholinguistics, corpus-studies, development of signed language assessments, detailed case studies, etc. – is crucial. Our work to date has been cross-sectional, meaning that our data on each child are limited to one point in a child’s development. There is a real need for longitudinal studies tracking sign language development in children with SLI over time (plus typically developing deaf children in comparison). Rice (2013, p.225) points out that data from a large longitudinal study of hearing monolingual English-speaking children in the USA suggests that “once acquisition of a particular language dimension begins, the children with SLI follow, on average, the same growth trajectories as children without SLI” – i.e. the gap between SLI and typical does not get wider, though nor does it close, over time. We cannot 26 assume that this would be the case for sign SLI, where sign input that the children are getting may be of lower quantity and quality compared to what would be the case for hearing children with SLI. Finally, there is a chronic need for research into language interventions for children with SLI in signed languages. Although there is no “quick fix” for SLI in spoken languages, there is a growing evidence base of what works and what does not with respect to language interventions (Law et al., 2003; Law et al., 2012). The recommended methodology for evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions is the randomised control trial (Law et al., 2003), i.e. studies whereby children are randomly allocated to groups and where a comparison can be made between a group who receives the intervention and a group who does not. Randomised control trials require preliminary studies before they can be undertaken, but it is our enduring aim that others will take up this challenge in BSL and in other signed languages. It is hoped that the initial work that we have outlined in this chapter assists in this endeavour. 27 References Armon-Lotem, S. (2010). Instructive bilingualism: Can bilingual children with SLI rely on one language in learning a second one? Applied Psycholinguistics, 31, 29-36. Atkinson, J., Marshall, J., Woll, B., & Thacker, A. (2005). Testing comprehension abilities in users of British Sign Language following CVA. Brain and Language, 94, 233-248. Bedore, L., & Peña, E. (2008). Assessment of bilingual children for identification of language impairment: Current findings and implications for practice. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 11, 1–29. Bishop, D. V. M. (2006). Developmental cognitive genetics: How psychology can inform genetics. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 59, 1153-1168. Bishop, D. V. M (2014). Ten questions about terminology for children with unexplained language problems. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 49, 381-415. Bishop, D. V. M., North, T., & Donlan, C. (1996). Nonword repetition as a behavioural marker for inherited language impairment: evidence from a twin study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37, 391-403. Botting, N. (2002) Narrative as a tool for the assessment of linguistic and pragmatic impairments. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 18, 1-22. Brentari, D. (1998). A Prosodic Model of Sign Language Phonology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Brooks, P. & Kempe, V. (2012). Language development. Chichester, UK: Wiley. 28 Conti-Ramsden, G., Botting, N. & Faragher, B. (2001) Psycholinguistic markers for SLI. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 741-748. Crago, M., Paradis, J., & Menn, L. (2008). Cross-linguistic perspectives on the syntax and semantics of language disorders. In M. J. Ball, M. R. Perkins, N. Müller, & S. Howard (Eds.) The handbook of clinical linguistics. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. Pp.275289. de Bree, E., Rispens, J., Gerrits, E. (2007) Non-word repetition in Dutch children with (a risk of) dyslexia and SLI. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 21, 935–944. Denmark, T., Atkinson, J., Campbell, R., & Swettenham, J. (in press). How do typically developing deaf children and deaf children with autism spectrum disorder use the face when comprehending emotional facial expressions in British Sign Language? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. Dockrell, J., & Marshall, C. R. (in press). Assessing language skills in young children. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Emmorey, K. (2003). (Ed.). Perspectives on classifier constructions in sign languages. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Fenson, L., Dale, P. S., Reznick, J. S., Bates, E., Thal, D. J., & Pethick, S. J. (1994). Variability in early communicative development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 59(5). Ferjan Ramirez, N., Lieberman, A. M., & Mayberry, R. I. (2013). The initial stages of language acquisition begun in adolescence: When late looks early. Journal of Child Language, 40, 391-414. 29 Friedmann, N., & Novogrodsky, R. (2004). The acquisition of relative clause comprehension in Hebrew: A study of SLI and normal development. Journal of Child Language, 31, 661-681. Gallon, N., Harris, J., & van der Lely, H. K. J. (2007) Non-word repetition: an investigation of phonological complexity in children with Grammatical Specific Language Impairment (SLI). Journal of Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 21, 435-485. Gathercole, S., & Baddeley, A. (1990). Phonological memory deficits in language disordered children: Is there a causal connection? Journal of Memory and Language, 29, 336– 360. Genesee, F., Paradis, J., Crago, M. (2004). Dual language development and disorders: A handbook on bilingualism and second language learning. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing. Girbau, D., & Schwartz, R. G. (2007). Non-word repetition in Spanish-speaking children with Specific Language Impairment. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 42, 59–75. Hansson, K., Nettelbladt, U., & Leonard, L. B. (2000). Specific language impairment in Swedish. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 43, 848-864. Henry, L. A., Messer, D. J., & Nash, G. (2012). Executive functioning in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 53, 37–45. Herman, R., Holmes, S. & Woll, B. (1999). Assessing British Sign Language Development: Receptive Skills Test. Forest Bookshop. Gloucestershire, UK 30 Herman, R., Grove, N., Holmes, S., Morgan, G., Sutherland, H. & Woll, B. (2004). Assessing BSL Development: Production Test (Narrative Skills). City University Publication. Herman, R., Rowley, K., Mason, K., & Morgan, G. (2014). Deficits in narrative abilities in child BSL users with specific language impairment. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 49, 343-353. Hoff, E. (2006). How social contexts support and shape language development. Developmental Review, 26, 55-88. Kalnak, N., Peyrard-Janvid, M., Forssberg, H., & Sahlén, B. (2014). Non-word repetition: A clinical marker for SLI in Swedish associated with parents’ language-related problems. PLoS ONE 9(2): e8944. doi:10.371/journal.pone.0089544 Law, J., Garrett, Z., & Nye, C. (2003). Speech and language therapy interventions for children with primary speech and language delay or disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD004110. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004110 Law, J., Lee, W., Roulstone, S., Wren, Y., Zeng, B., & Lindsay, G. (2012). ‘What works’: Interventions for children and young people with speech language and communication needs. London, UK: Department for Education. (Research report DFE-RR247-BCRP10). Leonard, L. (1998). Children with Specific Language Impairment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Mann, W., & Haug, T. (2014). Mapping out guidelines for the development and use of sign language assessment: Some critical issues, comments and suggestions. In D. Quinto31 Pozos (Ed.) Multilingual aspects of signed language communication and disorders. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters. Pp. 123-139. Mann, W., Marshall, C. R., Mason, K., & Morgan, G. (2010). The acquisition of sign language: The impact of phonetic complexity on phonology. Language Learning and Development, 6, 60-86. Marini, A., Tavano, A., & Frabbro, F. (2008), Assessment of linguistic abilities in Italian children with specific language impairment. Neuropsychologia, 46, 2816–2823. Marshall, C. R. (2014). Word production in children with developmental language impairments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 369: 20120389. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0389 Marshall, C. R., Denmark, T., & Morgan, G. (2006). Investigating the underlying causes of SLI: A nonsense sign repetition test in British Sign Language. Advances in SpeechLanguage Pathology, 8, 347-355. Marshall, C. R., Mann, W., & Morgan, G. (2011). Short term memory in signed languages: Not just a disadvantage for serial recall. Frontiers in Psychology 2:102. doi: 10.3389/ fpsyg.2011.00102 Marshall, C. R., Mason, K., Rowley, K., Herman, R., Atkinson, J., Woll, B., & Morgan, G. (in press). Sentence repetition in deaf children with Specific Language Impairment in British Sign Language. Language Learning and Development. 10.1080/15475441.2014.917557 32 Marshall, C. R., Rowley, K., Mason, K., Herman, R., & Morgan, G. (2013). Lexical organisation in deaf children who use British Sign Language: Evidence from a semantic fluency task. Journal of Child Language, 40, 193-220. Marshall, J., Atkinson, J., Smulovitch, E., Thacker, A., & Woll, B. (2004). Aphasia in a user of British Sign Language: Dissociation between sign and gesture. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 21, 537-554. Mason, K., Rowley, K., Marshall, C. R., Atkinson, J. R., Herman, R., Woll, B., & Morgan, G. (2010). Identifying SLI in Deaf children acquiring British Sign Language: Implications for theory and practice. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 28, 33-49. Meristo,. M., Hjelmquist, E., & Morgan, G. (2012). How access to language affects theory of mind in deaf children. In M. Siegal & L. Surian (Eds.). Access to language and cognitive development. New York : Oxford University Press. (pp. 44–61) Merritt, D., & Liles, B., (1987), Story grammar ability in children with and without language disorder: story generation, story retelling, and story comprehension. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 30, 539–552. Messer, D., & Dockrell, J. (2013). Children with word finding difficulties: continuities and profiles of ability. First Language, 33, 433-448. Morgan, G. (2014). Critical period in language development. In The Encyclopaedia of Language Development. P. Brooks & V. Kempe (eds). SAGE. Pp. 115-118. 33 Morgan, G., Herman, R., & Woll, B. (2007). Language impairments in sign language: breakthroughs and puzzles. International Journal for Language and Communication Disorders, 42, 97-105. Morgan, G., & Woll, B. (2007). Understanding sign language classifiers through a polycomponential approach. Lingua, 117, 1159-1168. Newbury, D. (2013). The genetics of developmental disorders. In C. R. Marshall (Ed.) Current issues in developmental disorders. Hove, UK: Psychology Press. Pp. 46-72. Norbury, C. F. & Bishop, D. V. M., (2003), Narrative skills of children with communication impairments. International Journals of Language and Communication Disorders, 38, 287– 313. Paradis, J. (2010). The interface between bilingual development and specific language impairment. Keynote article for special issue with peer commentaries. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31, 3-28. Paradis, J., Schneider, P., & Sorenson Duncan, T. (2013). Discriminating children with language impairment among English language learners from diverse first language backgrounds. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 56, 971-981. Pinker, S. (1994). The language instinct. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company. Pyers, J., & Senghas, A. (2009). Language promotes false-belief understanding: Evidence from Nicaraguan Sign Language. Psychological Science, 20, 805-812. Quinto-Pozos, D. (2007). Can constructed action be considered obligatory? Lingua, 117, 1285-1314. 34 Quinto-Pozos, D., Forber-Pratt, A., and Singleton, J. L. (2011). Do developmental communication disorders exist in the signed modality? Perspectives from professionals. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 42, 423-443. Reilly, S., Tomblin, B., Law, J., McKean, C., Menash, F. K., Morgan, A., Goldfield, S., Nicholson, J. M., & Wake, M. (2014). Specific language impairment: A convenient label for whom? International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 49, 416-451. Reilly, S., Wake, M., Ukoumunne, O. C., Bavin, E., Prior, M., Cini, E., Conway, L., Eadie, P., & Bretherton, L. (2010). Predicting language outcomes at 4 years of age: Findings from Early Language in Victoria Study. Pediatrics, 126, E1530-E1537. Rice, M. L. (2013). Language growth and genetics of specific language impairment. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 223-233. Rice , M. L., & Wexler, K . (1996). Toward tense as a clinical marker of specific language impairment in English-speaking children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 39, 1239-1257. Rothweiler, M., Chilla, S., & Babur, E. (2010). Specific language impairment in Turkish: Evidence from case morphology in Turkish-German bilinguals. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 24, 540-555. Schick, B., Marschark, M., & Spencer, P. E. (Eds.). (2006). Advances in the sign language development of deaf children. New York: Oxford University Press. Schick, B. (2004). Acquiring a visually-motivated language: Evidence from diverse learners. In Schick, B., Marschark, M., & Spencer, P. (eds.).Advances in the Sign Language 35 Development of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Children. New York: Oxford University Press. Schulz, P., & Friedmann, N. (2011). Specific language impairment across languages: Properties and possible loci. Lingua, 121, 333-338. Shaalan, S. (2010). Investigating grammatical complexity in Gulf-Arabic speaking with specific language impairment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University College London. Stokes, S.F., Wong, A. M-Y., Fletcher, P., & Leonard L.B. (2006). Nonword repetition and sentence repetition as clinical markers of specific language impairment: The case of Cantonese. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 219-236. Stokoe, W. C. (1960). Sign language structure: An outline of the visual communication systems of the American Deaf. Reprinted in (2005). Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 10, 1-37. Thordadottir, E. T., & Namazi, M. (2007). Specific language impairment in French-speaking children: Beyond grammatical morphology. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 698-715. Tomblin, J. B., Freese, P. R, & Records, N. L. (1992). Diagnosing specific language impairments in adults for the purpose of pedigree analysis. Journal of speech and Hearing Research, 35, 832-843. Tomblin, B., Records, N., Buckwater, P. Zhang, X., Smith, E., & O’Brien, M. (1997). Prevalence of specific language impairment in kindergarten children. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 40, 1245-1260. 36 Tribushinina, E., & Dubinkina, E. (2012). Adjective production by Russian-speaking children with specific language impairment. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 26, 554-571. van der Lely, H. K. J. (1997). Language and cognitive development in a grammatical SLI boy: Modularity and innateness. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 10, 75-107. van der Lely, H. K. J., & Harris, M. (1990). Comprehension of reversible sentences in specifically language impaired children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 55, 101-117. Wetherell, D., Botting, N., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (2007). Narrative in adolescent SLI: a comparison with peers across two different narrative genres. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 42, 593-605. Williams, D., & Lind, S. (2013). Comorbidity and diagnosis of developmental disorders. In C. R. Marshall (Ed.) Current issues in developmental disorders. Hove, UK: Psychology Press. Pp. 19-45. Woll, B., & Grove, N. (1996). On language deficits and modality in children with Down Syndrome: A case study of twins bilingual in BSL and English. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 1, 271-278. Woll, B., & Morgan, G. (2012). Language impairments in the development of sign: Do they reside in a specific modality or are they modality-independent deficits? Bilingualism, Language & Cognition, 15, 75-87. Woolfe, T., Herman, R., Roy, P., & Woll, B. (2010). Early vocabulary development in deaf native signers: a British Sign Language adaptation of the communicative development inventories. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 322-331. 37 38 Figures and tables Figure 1. Example of a nonsense sign in BSL. The clips show the start and end positions and the arrow shows the path of movement. i Indeed, there is debate over which term should be used, with other terms such as ‘primary language impairment’, ‘developmental language disorder’, ‘speech and language difficulties’, ‘speech and language disorder’ and ‘developmental dysphasia’ being used in the research and applied literature (Bishop, 2014). We use the term ‘specific language impairment’ throughout this chapter, whilst recognising that other researchers may prefer another term. 39