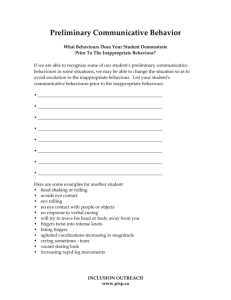

Experiences of restrictive practices

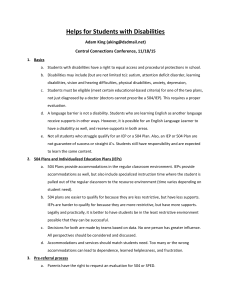

advertisement