Aristotle and the Good Life - The Richmond Philosophy Pages

advertisement

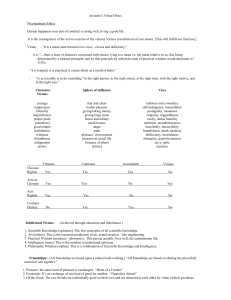

Aristotle and the Good Life You should aim to have read the texts set out in the reading list. To begin (and as a minimum) I suggest you start with NE I,II,X. Next read the Crisp article followed by Norman (chaps 3&4) and Hughes (chap 3). For a brief overview of Aristotle consult Barnes. 1. Context Intellectual background and interests. Works in practical philosophy - Magna Moralia (not by A). Eudemian Ethics. Nichomachean Ethics. (EE IV-VI = NE V-VII). Politics. NE X9 - ethics and political science parts of a single enquiry. Edited lecture notes. The Greek city state. Male citizen body who participated in the governance of the state. Relatively small social and public space. Attitude to those outside of that culture. Prior to impact of Christianity Aristotle 384-322 BCE. 2. The purpose and method of ethics Ethics is concerned with praise and blameworthy actions and the states of character of (rational) agents. The focus is on the question of how one ought to live, of what the good life is. Ethics aims to elucidate the good for individual and community (NE I 2). Ethics centrally interested in virtues (and vices) - a virtue (arete) is a disposition of character which has the right pattern of motivation. Virtues include courage, temperance, generosity, magnanimity, truthfulness, justice. Significance of the emotions and their development. Theoretical and practical knowledge. Ethics is not a fit subject for the young and inexperienced. Naturalism - ethics grounded in an account of human nature Cannot expect precision beyond that which is appropriate for the subject matter (NE I 3). Look to the opinions of the wise and the many. 3. The human good Action - means and ends. The teleological framework. Everything has an end or purpose (telos): knives, eyes, foxes and humans. The ultimate end of human action is happiness; it is an end sought for its own sake; it is complete and self-sufficient. 'Happiness'. The concept of eudaimonia - flourishing, well-being, a fulfilled life. Richer notion of happiness than mere pleasure. But N.B. the contribution of pleasure. Candidates for the eudaemon life (I 4,5): a life of money making; a life of sensual pleasure; a life in which one is well thought of. Not capture what we can mean when we talk of a fulfilled life or of what is to enjoy wellbeing or to flourish or to be truly happy. 1 4. Function and the function argument The function argument (NE I 7). The good life for some thing is a life spent in pursuit and realisation of its end. The ultimate end of some kind (say a species) can be identified by a consideration of its distinctive function (ergon), capacities or characteristic activity. An X achieves its goal or end (telos) when it functions properly. Humans share features with all other kinds of organisms - at the most general of levels - all organisms have as functions survival, growth, reproduction. Humans are distinguished by possession of reason (and language). Possession of logos is essential to being human. The human function is the exercise of reason. As an essentially rational creature the good life must a life guided by reason. Aristotle tell us that 'human good turns out to be activity of the soul exhibiting (in accordance with) excellence, and if there are more than one excellence (virtue), in accordance with the best and most complete' (NE I 7). 'Happiness is an activity of the soul in accordance with perfect virtue' (NE I 13). At this stage the detail of such a life remains to be specified and Aristotle goes on to analyse the nature of the virtues in the following books. The concept of soul. The form or organising principle, animating the matter of our body. Human flourishing consists in performing well those activities of which our soul renders us capable (Hughes p.37). Across a complete life happiness, well-being, flourishing consists in the exercise of the virtues. A person acts in certain ways because she sees that it is the right thing to do and is moved to act for its own sake. Pleasure in the action. 5. The virtues and the mean Moral virtue (or virtues of character) and intellectual virtue. Key role of practical wisdom (phronesis). The highest skill or virtue of the mind in thinking about practical matters to see what is good for oneself and for men in general. The practically wise man (phronimos) can judge what ought to be now in this particular situation. Develop virtue through being brought up properly, habituation, engagement with others and practice. Performing just actions, being generous and so on leads one to develop that kind of character and to choose such actions for their own sake. Virtues are dispositions developed through practice and habituation. The importance of having the right kind of emotional responsiveness. To possess a virtue is to observe the mean between excess and deficiency (NE II 6, 8-9). Virtue is a mean between two vices. Consider e.g. the virtues courage and good temper. The doctrine of the mean is not a doctrine of moderation (consider the failure involved in not being angry enough sometimes) and it is not an appeal to a method of (quasi) quantification or measurement - c.f. mean 'in relation to the thing' 2 The doctrine of the mean telling us to have the right motivations to undertake the appropriate action to the right degree on the right occasion towards the right people. Empty and unhelpful? Conflict of virtues and judgements . The role of practical wisdom. The rationality of the emotions - our responses properly attuned to the states with which we are confronted. The unity of the virtues. Of the challenges and questions which arise let's consider some of the following. 6. Instrumentalism? Flourishing and the virtues. The various virtues are pursued for their own sake and for the sake of eudaimonia. So, should we regard happiness as a more final end? We always choose happiness for its own sake. This is not the case with honour, pleasure, intelligence, and good qualities generally. We do pursue them partly for their own sake, but also for the sake of happiness in the belief they will be instrumental in promoting it (NE I 7). But why should being pursed for their own sake and for that of something else render virtues inferior? See Norman pp 28-31 for discussion on this and related issues. We should see A's point as being that happiness is not the same kind of thing as a virtue such as courage, but that happiness is constituted by possession of them. 7. The consistency of Aristotle's account : inclusive and dominant goods Happiness or flourishing is then a state enjoyed in virtue of being virtuous in character and acting accordingly. At the risk of oversimplification there is a dispute as to whether we should understand happiness to consist in one kind of activity, for whose sake we ultimately do everything else (the dominant interpretation). Or, whether happiness consists in a package of activities (the inclusivist interpretation). The picture through much of NE is that happiness consists in a range of goods or activities - a life guided by practical wisdom. This encourages the inclusivist view of e.g. Ackrill. In NE X 7 we are told that happiness is to be identified with just one good: it consists in a single rational activity, that of philosophical contemplation. This looks as clear a statement of the dominant view as one could wish for. Then in NE X 8 it appears that a flourishing life consists in the multifaceted activities of good citizenship. Is Aristotle just inconsistent? Perhaps a problem in the editing of the lectures? The life for the few and the life for the many? Is the inclusivist interpretation the more plausible? Again note the constitutive relationship between a set of goods and activities and a fulfilled life. One suggestion - could we see contemplation as the best element of the 3 good life, but one which is not the good for the whole human being since we are not in fact gods or pure intellects? Another suggestion (stretching perhaps what the text can stand!) - there is an interplay and interdependence between practical and theoretical reasoning in a fulfilled life. In acting as well as we can we understand what it means to act in that fashion and the way in which our conduct relates to the structure of one's life and the world in which that life unfolds. Theoretical reflection for its own sake and directed at a life guided by practical wisdom is how we can come to give fullest expression to our distinctive capacity of reason. C.f. Hughes pp. 45-51 8. Problems with the function argument Analogy with artefacts - who or what determines the function of humans? Analogy with organs - the function of an organ specified in relation to the creature of which it is a part. Of what whole in the individual human a part? But appeal to the notion of flourishing being connected to essence? But is reason or logos our essence? Why should our flourishing be determined by our unique feature(s)? What is characteristically human? One might emphasise the continuities with animals. The teleological background Women and slaves - a problem? 9. Virtue and morality Is the Aristotelian account unduly conservative? Narrow cultural space. Promotion of traditional virtues. Scope for reflection and criticism? Is it committed to egoism? Selfishness and moral egoism. The good life grounded in consideration of the self. The question of what kind of person to be opens space for seeing the needs of others as such. The virtuous criminal. I may employ great skill, intelligence, courage and judgement in my criminal activities. I may even be generous to the poor. There seems much to admire about my character, but my actions are wrong. How can the Aristotelian approach account for this? Challenges to naturalist accounts of morality. 4