here - The Communication Trust

advertisement

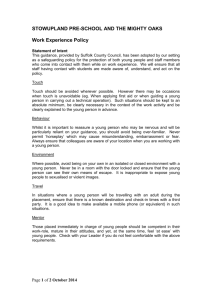

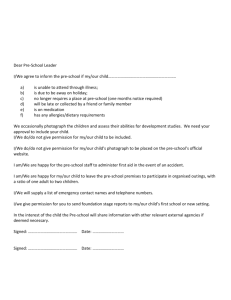

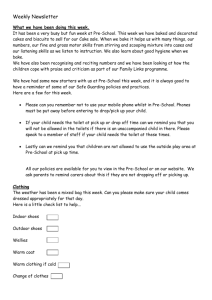

Oral language skills and poverty ‘I have children coming into our school who don’t know their own name – and don’t even know that they have a name.’ Headteacher, Hull ‘The truth is a lot of our white children in nursery have fewer words of English than bilingual children.’ Headteacher of a multi-ethnic, multilingual school in Lambeth Language skills are a critical factor in social disadvantage and in the intergenerational cycles that perpetuate poverty. Poor language skills are the key reason why, by the age of 22 months, a more able child from a low income home will begin to be overtaken in their developmental levels by an initially less able child from a high-income home – and why by the age of five, the gap has widened still more. On average a toddler from a family on welfare will hear around 600 words per hour, with a ratio of two prohibitions (‘stop that’, ‘get down off there’) to one encouraging comment. A child from a professional family will hear over 2000 words per hour, with a ratio of six encouraging comments to one negative (Hart and Risley, 2003). Low income children lag their high income counterparts at school entry by sixteen months in vocabulary. The gap in language is very much larger than gaps in other cognitive skills (Waldfogel and Washbrook, 2010). More than half of children starting nursery school in socially disadvantaged areas of England have delayed language - while their general cognitive abilities are in the average range for their age, their language skills are well behind (Locke et al, 2002) A survey of two hundred young people in an inner city secondary school found that 75% of them had speech, language and communication problems that hampered relationships, behaviour and learning (Sage, 1998) Vocabulary at age 5 has been found to be the best predictor (from a range of measures at age 5 and 10) of whether children who experienced social deprivation in childhood were able to ‘buck the trend’ and escape poverty in later adult life (Blanden, 2006). Researchers have found that, after controlling for a range of other factors that might have played a part (mother’s educational level, overcrowding, low birth weight, parent a poor reader, etc), children who had normal non-verbal skills but a poor vocabulary at age 5 were at age 34 one and a half times more likely to be poor readers or have mental health problems and more than twice as likely to be unemployed as children who had normally developing language at age 5 (Law et al., 2010). The cycle can be broken Research shows that it is not poverty per se which matters most. The child’s communication environment (the early ownership of books, trips to the library, attendance at pre-school, parents teaching a range of activities and the number of toys and books available) is a more important predictor of language development at two, and school entry ‘baseline’ scores at four than socio-economic background alone (Roulstone et al , 2011) Work with parents is vital. ‘Growing up in Scotland’ longitudinal research has found that progress in language amongst 3-5 year olds was most affected by factors in the home 1 environment, while progress in problem-solving was more affected by external factors such as type of pre-school education attended Intervention needs to be early. The Scottish research found that progress in language amongst 3-5 year olds was strongly predicted by language skills at 2, and that for children whose parents had no or lower qualifications, poor early communication skills were highly likely to persist through the pre-school(3-5)period ‘Any strategies for improving school readiness via the pre-school setting need to include , for more disadvantaged children, strategies which seek to influence the child’s home environment and parenting experiences at the same time..to ensure that children’s cognitive ability is maximised... such strategies should focus on the quality of the parent-child relationship and frequency of home learning activities’ Growing up in Scotland, 2011 Why does poor language affect the life chances of children in low income families Poor language predicts poor literacy skills. At the age of six there is a gap of a few months between the reading age of children who had good oral language skills at 5, and those with poor oral language skills at 5. By the time they are 14, this gap has widened to five years’ difference in reading age (Hirsch, 1996) Poor language also predicts behaviour problems. Two thirds of 7-14 year olds with serious behaviour problems have language impairment (Cohen et al 1998).65% of young offenders have speech, language and communication difficulties, but in only 5% of cases were they identified before the offending began (Bryan et al, 2008). Poor language and communication skills in school leavers reduces the probability of getting into employment. Employers now rate communication skills as their highest priority, above even qualifications. 47% of employers in England report difficulty in finding employees with an appropriate level of oral communication skills (UK Commission for Employment and Skills, 2009). 2 What works in interrupting the cycle Early intervention There is good evidence that co-ordinated, community-wide, interagency strategies to upskill the children’s workforce and get key messages across to parents of young children can improve language skills across the community, with a particular impact on disadvantaged children. Stoke Speaks Out is a multi-agency strategy set up in 2004 to tackle the high incidence of speech and language difficulties in Stoke-on-Trent. It aims to support attachment, parenting and speech and language issues through training, support and advice. It developed from local Sure Start initiatives which identified that between 60% and 80% of children assessed in Stoke at age three to four years had a language delay. Stoke Speaks Out developed a multi-agency training framework for all practitioners working in the city with children birth to seven years or their families. The training has five levels, ranging from awareness-raising to detailed theoretical levels, and was jointly written by the project team of speech and language therapists, a clinical psychologist, a midwife, play workers, teachers and a bilingual worker. All levels have an expectation that the practitioner will create change in their working environment. In addition the initiative has developed resources for parents, including a model for toddler groups to follow which enhances language development, and a website offering practical information for parents to help with children's language development. ‘Talking walk-ins’ provide drop in sessions at Children’s Centres where parents can get advice from speech and language therapists. As a result of the initiative, the percentage of three to four year olds with significant language delay in the area has reduced from 64% in 2004 to 39% in 2010. The work in Stoke is one example; similar impact has been achieved in other local areas. In Sandwell, a ‘Time to Talk’ community-wide initiative reduced the percentage of children whose language gave cause for concern from 32 to 21%. In Brighton and Hove, a two year project ‘Talking and Learning together’ developed a local, accessible and integrated service empowering parents/carers and early years staff to help all children learn to talk. The results show a huge rise in the number of children entering Key Stage 1 (at the age of five) with age-appropriate language skills, and a significant decline in the number of referrals to the speech and language therapy service. The national Every Child a Talker programme has built on initiatives like these and has already demonstrated rapid impact over a short period; recent data shows a drop of seven percentage points in children with poor language skills over just seven months in the early years settings involved. Work in schools to teach children important language and communication skills Work on oral language is not currently given priority in schools. Literacy and numeracy dominate. And yet: Children aged nine with poor reading comprehension made greater improvements in reading when provided with an intervention to develop their oral language than they did 3 when provided with an intervention directly targeting reading comprehension skills (Snowling et al, 2010) Socially disadvantaged children can catch up with other children in language skills after just nine months if their teachers are trained to have the right kind of conversations with them(Hank and Deacon, 2008) Small group interventions to boost language skills have a rapid, measurable effect on vocabulary and other aspects of language development – themselves very strong predictors of later academic achievement. Key Stage 1 children (ages five to seven) receiving one such intervention, for example, made on average 14 months progress on a test of vocabulary and language development after just ten weeks of twice weekly group help. It is never too late. Re-conviction rates for offenders who studied the English Speaking Board’s oral communication course fell to 21% (compared to the national average of 44%) greater than the fall to 28% for offenders who followed a general education course (Moseley et al, 2006). Jean Gross, Communication Champion September 2011 References Blanden, J. (2006) Bucking the Trend – What enables those who are disadvantaged in childhood to succeed later in life? London: Department for Work and Pensions. Bryan, K. (2008) Speech, Language and Communication difficulties in juvenile offenders. In C. Hudson (ed) The Sound and the Silence: Key Perspectives on Speaking and Listening and Skills for Life. Coventry: Quality Improvement Agency. Cohen, N., Barwick, M., Horodezky, N., Vallance, D. & Im, N. (1998). Language achievement, and cognitive processing in psychiatrically disturbed children with previously unidentified and unsuspected language impairments. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39, 865–877. Hank, N., & Deacon, S.H. (2008). Building Vocabulary in High Poverty Children. Literacy Today. 54, 29. Hart, B., and Risley, T. (2003). The early catastrophe: The 30 million word gap by 3. American Educator, 27(1), 4-9. Hirsch (1996) The Effects of Weaknesses in Oral Language on Reading Comprehension Growth cited in Torgesen, J. (2004). Current issues in assessment and intervention for younger and older students. Paper presented at the NASP Workshop. Law, J. et al (2010) Modelling developmental language difficulties from school entry into adulthood. Journal of speech, language and hearing research, 52, 1401-1416 Locke, A., Ginsborg, J., and Peers, I. (2002). Development and disadvantage: Implications for early years and beyond. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 37(1), 3-15 Moseley, D.; Clark, J.; Baumfield ,V.; Hall, E.; Hall, I.; Miller, J.; Blench, G.; Gregson, M.; Spedding, T. (2006). The impact of ESB oral communication courses in HM Prisons - an independent evaluation. UK Online: Learning and Skills Development Agency. 4 Parkes, a. and Wight, D. (2011) Growing Up in Scotland - 2011: Research Findings No.3/2011: Growing Up in Scotland - Parenting and Children's Health Roulstone, S. et al (2011) Investigating the role of language in children’s early educational outcomes DfE Research Report 134 Sage, R., (1998) Communication Support for Students in Senior Schools. Leicester: University of Leicester Snowling, M., Clarke, P., Hulme, C. (2010) Reading comprehension: nature, assessment and teaching. London: Economic and Social Research Council UK Commission for Employment and Skills (2009) The Employability Challenge http://www.ukces.org.uk/tags/employability-challenge-full-report Waldfogel, J. and Washbrook, E. (2010) Low income and early cognitive development in the U.K. London: Sutton Trust 5