Swinton local history pamphlet

advertisement

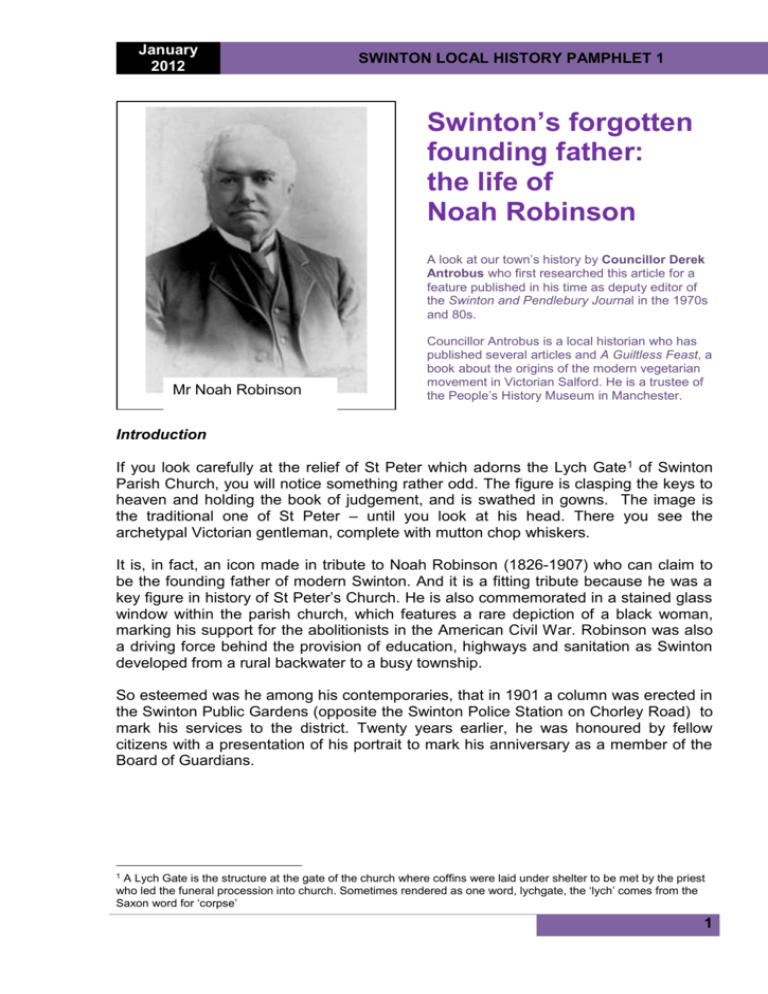

January 2012 SWINTON LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLET 1 Swinton’s forgotten founding father: the life of Noah Robinson A look at our town’s history by Councillor Derek Antrobus who first researched this article for a feature published in his time as deputy editor of the Swinton and Pendlebury Journal in the 1970s and 80s. Mr Noah Robinson Councillor Antrobus is a local historian who has published several articles and A Guiltless Feast, a book about the origins of the modern vegetarian movement in Victorian Salford. He is a trustee of the People’s History Museum in Manchester. Introduction If you look carefully at the relief of St Peter which adorns the Lych Gate 1 of Swinton Parish Church, you will notice something rather odd. The figure is clasping the keys to heaven and holding the book of judgement, and is swathed in gowns. The image is the traditional one of St Peter – until you look at his head. There you see the archetypal Victorian gentleman, complete with mutton chop whiskers. It is, in fact, an icon made in tribute to Noah Robinson (1826-1907) who can claim to be the founding father of modern Swinton. And it is a fitting tribute because he was a key figure in history of St Peter’s Church. He is also commemorated in a stained glass window within the parish church, which features a rare depiction of a black woman, marking his support for the abolitionists in the American Civil War. Robinson was also a driving force behind the provision of education, highways and sanitation as Swinton developed from a rural backwater to a busy township. So esteemed was he among his contemporaries, that in 1901 a column was erected in the Swinton Public Gardens (opposite the Swinton Police Station on Chorley Road) to mark his services to the district. Twenty years earlier, he was honoured by fellow citizens with a presentation of his portrait to mark his anniversary as a member of the Board of Guardians. 1 A Lych Gate is the structure at the gate of the church where coffins were laid under shelter to be met by the priest who led the funeral procession into church. Sometimes rendered as one word, lychgate, the ‘lych’ comes from the Saxon word for ‘corpse’ 1 January 2012 SWINTON LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLET 1 Life in Brief Robinson was born in Chapel Street, Salford. At the age of six, he came to Swinton where his father, Thomas Robinson, had made his home at Ivy Cottage, Wardley Lane, Worsley – close to the Morning Star public house in the Wardley2 area. His father had built the Albert Mill which stood until the latter decades of the 1900s by St Peter’s Church, behind the site of the current Swinton police station. He married a widow, Mrs Howarth in 1867. She died within a year and they had no children. Mrs Howarth had a daughter from her first marriage who continued to live with Robinson. For much of his life he lived at Poplar House, 216 Chorley Road, which stood opposite St Peter’s Church. He died there in July 1907, a few days before his 81st birthday. He left in his will nearly £15,000. Robinson was buried at Eccles Parish Church. On the day of his funeral, the Albert Mill closed and flags were flown at half-mast. The streets of Swinton were lined with people on both sides to pay tribute as the cortege went past. He attended school in Swinton under the tutelage of his uncle Luke Smith. In his Reminiscences he described the Swinton he first knew as “in a very primitive state”. Writing in 1901, he recalled: “When I went to school , 69 years ago, down Burying Lane, to Swinton, which is now called Station Road, there was neither pavement nor edging stones”. No streets were lit and people had to fetch domestic water from pumps and wells. His work Robinson’s life was dedicated to seeking to remedy this ‘primitive state’. He was active during a period of great change. According to his Reminiscences, he possessed an accounts book which recorded the changing population and rateable value of Swinton. In 1815, the population was around 5,500 (with a rateable value of £7,300) and changed little until the 1840s. Robinson notes the arrival of the Swinton Industrial Schools3 and the decisions of the trustees of the Duke of Bridgewater to open up their extensive landholdings in Swinton for building as contributing to growth. But the most significant factor was the establishment of a Local Board (see below) which brought clean water and drainage to the area. By 1851, the population had risen to 10,188 with a rateable value of £20,095 and by 1901 the number of citizens stood at 30,954 with a rateable value £115,726. 2 The Sindsley Brook rises at Clifton and runs alongside the former Brook Tavern (now converted to a supermarket) and along Moorside Road and marks the boundary between the old towns of Swinton and Worsley. Wardley was historically part of Worsley. Since 1974, when the towns amalgamated, Wardley has been incorporated into a Swinton ward. The motorway – which divided Wardley from the rest of Worsley - marks a more modern and visible boundary. In Robinson’s time, Swinton was part of the Worsley township, in the parish of Eccles and in the Hundred of Salford. It changed to becoming its own parish and own local authority. 3 The Swinton Industrial Schools were basically a training centre for poor children. Built by the Manchester Poor Law Guardians in 1846, they occupied the site of the Swinton Town Hall. 2 January 2012 SWINTON LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLET 1 He involved himself in all the local institutions whose role was to improve the lot of the people of Swinton. To understand his influence, it is necessary to have a rough idea of what those institutions were. At the start of the 19th century, local government was organised around the church with the local Anglican parish being the centre of political as well as religious life. The parish was required to elect an Overseer of the Poor (often a churchwarden) and a Surveyor of Highways. But this was usually too great a burden for local communities. In some places such as Worsley, there continued the Court Leet – the ancient manorial court – which was primarily responsible for nuisances, weights and measures, and keeping the peace. (Larger towns from 1835 were able to consolidate all these powers under a borough council – often know as the Corporation). From the 1830s, the institutions of local government were reformed. The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 – forever associated with the workhouse – also combined parishes into Unions administered by elected officials known as the Poor Law Guardians. Robinson was a Guardian from 1865 until 1901, representing the township of Worsley (which encompassed Swinton) on the Barton-upon-Irwell Board of Guardians. In response to outbreaks of cholera, the Public Health Act of 1848 allowed for setting up Local Boards of Health, responsible for housing, sanitation, and drainage. These bodies were renamed Local Boards and given wider powers by the 1858 Local Government Act. Again, Robinson was a member of the Local Board from 1867 to 1875. Turnpike Trusts – ad hoc bodies established by Parliament to improve and maintain highways and charge a toll – were more effective than the Parish Surveyor. Robinson’s career in public service seems to have started in 1841 when he recalls keeping the highways accounts for Swinton and so it is fitting to start by looking at the development of highways. Robinson recalled how the Surveyor for Pendlebury levied a 10 pence (5p) rate 4 which was the maximum rate allowed. But that did not raise enough money to complete the stretch of Station Road from the Windmill Inn in Pendlebury to the Swinton boundary. Fortunately, the law did not prescribe how many times the Surveyor could levy a rate in any one year – so he raised the rate three times to pay for the work. According to Robinson, this prompted the Swinton Surveyor to pay, by levying two tenpence rates, for the improvement of Station Road from the Bull’s Head so the whole stretch was completed. But Robinson believed that Swinton benefited most from the establishment of turnpike roads and in particular the passing in 1836 of the Pendleton Road Trust Bill which allowed commissioners to borrow money to cut a new road from the Morning Star to The rate determined the amount ratepayers were required to pay. Each property had a rateable value – an estimate of how much it was worth. The rate was levied at x amount in the pound. So for every pound of rateable value, the ratepayer would pay x. Thus a property valued at £50 levied at ten pence in the £, would pay 50 x 10 pence. 4 3 January 2012 SWINTON LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLET 1 Lynnyshaw (sic) thus improving the connection between Walkden and Swinton. Altogether, the Pendleton Bill provided for 23 miles of road to be built, paid for by tolls to be collected at toll bars at Pendleton, Irlam, Pendlebury, Swinton and Agecroft. At some of the toll bars there were weighing machines as vehicles (horse-drawn in those days) were charged by weight. When toll roads were abolished, the rates in Swinton went up by 1s 4d (about 7p) in the £ as the cost of maintenance switched from the road user to the ratepayer. The enormous burden this put on local communities was recognised and the Local Government Act of 1888 vested responsibility for the upkeep of main roads in the newly-created county councils. Robinson’s first elected position as a Guardian for the Barton Union, administering the Poor Law, seems to have been a consequence the Cotton Famine starting in 1862. The Cotton Famine was the period during the American Civil War when the blockade of southern ports mean no cotton was being exported the mills of Lancashire. This led to the closure of mills and terrible poverty and suffering. Robinson sought to relieve the poor with the Rev Dr Alfred Dewes5 and the Rev Thomas Wilson, both clergy at Christ Church, Pendlebury. Robinson was closely involved with the growth of the church in Swinton and so he would have been involved in administering relief. This “very sad year for Swinton”, according to Holland, was the year Robinson “commenced a career of usefulness in Swinton which did not cease until a short time before his death”. Robinson himself recalled in December 1882: “Twenty years ago, a black scourge hung over Swinton. The cotton famine had begun to make itself manifest. I was looking over my relief-book, and I find the relief-committee commenced its operations on the 20th August 1862 and it was 1865 before we could close the book. “I was appointed a member of the relief committee and I saw many painful scenes during my visiting of people out of work through no fault of their own, which I hope I shall never see again nor that anyone here may witness such a time.” In the same speech he says that he was then nominated for election as a Guardian without being consulted at all – the first he knew about it was when he was congratulated by one William Yates on his way to church one Sunday morning! He was elected in 1864 and retired in 1901, having served as chairman in 1870-1. It was Robinson’s service as a Guardian which led him to confront probably the greatest issue of the time which led to the establishment of Swinton's first local authority – the Local Board established in 1867. Public health had been a concern since the early years of the century. In particular, outbreaks of cholera saw a massive death toll in European cities throughout the period. Cholera was proven in 1854 to arise from polluted water and water pollution was classified as a ‘nuisance’ and thus dealt with by the manorial Court Leet. The 1848 Dr Dewes, born in Coventry in 1825, was curate at St John’s, Pendlebury, and later the first vicar of Christ Church from 1859 until 1874 when he took over the newly-built St Augustine’s. 5 4 January 2012 SWINTON LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLET 1 Nuisance Removal Act allowed Guardians to appoint local committees to deal with nuisances and the first time this arose in the area was in 1853 with what Robinson calls ‘a slight outbreak of cholera’. A more severe outbreak occurred in 1866 – the fourth and final pandemic to afflict Europe – and on Sunday, September 9th, several deaths were reported in Swinton. A policeman called on Robinson to seek advice on what to do with the bodies. He immediately went with the policeman to see Dr Dorning, then medical officer for Worsley. The situation was recognised as being serious and the two men settled on the idea that a local committee needed to be set up and an Inspector of Nuisances appointed. Robinson then travelled to Patricroft the same night to call upon the Clerk to the Barton Union who immediately sent out messengers summoning a meeting of the Guardians the following morning. That meeting appointed a committee which met each evening with Dr Dorning to hear his report and act on his advice. Eighteen deaths were reported and this caused great alarm throughout the area, including neighbouring Salford where the borough council urged the Barton Union to take further action. One suggestion proffered was to incorporate Pendlebury, historically part of Pendleton, into the borough. This was discussed at a public meeting involving the Borough Council and the Barton Union at the Royal Oak Hotel, Pendlebury. The Barton Union agreed to appoint a permanent Inspector of Nuisances and this satisfied Salford that the issue was being addressed. It soon became clear, however, that without a proper system of drainage there could be no effective solution to water pollution. The Local Government Act of 1858 had replaced Local Boards of Health with more powerful local government agencies known simply as Local Boards. Robinson saw that this was the way forward and a group of ratepayers put forward a proposal to establish such a Board for Swinton. A public inquiry was held at the Bull’s Head Hotel in Swinton in early 1867 and the session lasted just half-an-hour, no objections being raised. The Swinton Local Board, which also covered the majority of the neighbouring township of Pendlebury, met for the first time in May 1867 at St Peter’s School in Swinton. It changed its name to Swinton and Pendlebury Local Board in 18696. The new Board set to work in earnest, and immediately concluded agreements with the Manchester Corporation for the supply of water – which until then had to be carried from pumps and wells – and with the Salford Corporation for the supply of gas. This led to much disruption as roads were dug up to lay new pipes. In September, 1868, however, the water supply for Swinton was turned on for the first time. In the same month, the streets of Swinton were lit for the first time. A survey was undertaken and contracts let to develop a drainage system for the area. For Robinson, these improvements were the reason that the town grew so quickly thereafter. Robinson remarked in 1882 how his duties as a Guardian took him to the workhouse and observed how few who ended there could read or write. He was convinced that 6 Following the Local Government Act 1894, Swinton became a civil parish, and the area of the local board became Swinton and Pendlebury, an urban district of the administrative county of Lancashire. In 1907 there were exchanges of land with the neighbouring Worsley Urban District, and in 1933 most of Clifton and a part of Prestwich Urban District were added to Swinton and Pendlebury. 5 January 2012 SWINTON LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLET 1 education was a way of avoiding poverty and through his association with St Peter’s Church, did his best to promote schooling – for him, the 1870 Elementary Education Act which made school places available to all up to the age of 13 had come “not a moment too soon”. Swinton had historically been part of the parish of Eccles. A chapel was built in Swinton in 1791 and it was only 1865 that it became a parish in its own right, the Rev Henry Robinson Heywood being the vicar. A new church was completed in 1870 to replace the chapel and Robinson appears to have supervised the contractual arrangements – he was present when the topstone was laid and there to witness the removal of scaffolding. He was parishioners’ warden7 at the church from 1871 until 1890. In 1887 a decision was taken to build a new school at St Peter’s and Robinson, who for 34 years until 1898 was treasurer of the School, was called upon to cut first sod a mark of his prominence in advancing education locally. In his Reminiscences he devotes a whole section to describing the progress of education in the vicinity, praising the neighbouring town of Walkden in particular for the foresight of its citizens in providing cheap education from the earliest times. Robinson was proud of these achievements and he certainly played a significant role in modernising the machinery of local government in Swinton and Pendlebury and advancing the cause of education. But he is also a bridge between the antiquated, medieval system and one more befitting an industrial age. It is interesting to note that the last meeting of the Worsley Court Leet in 1888 appointed Robinson the Constable for the district. The county authorities also sought to honour him by making him a Justice of the Peace – a position he declined. But other honours were bestowed on him. In December 1882 a ceremony took place to mark his years of service as a Guardian. He was presented with a portrait of himself sitting in the Overseer’s Chair. In 1901, the Noah Robinson memorial, marking his retirement as a Guardian, was unveiled in the Swinton Public Gardens in the presence of Robinson, the local MP Mr O. Leigh Clare, and Mr H. A. Heywood, of the county council. It was inscribed: “Erected to commemorate the services rendered to the district by Noah Robinson who for more than 36 years filled the post of Guardian of the poor and also discharged many other public duties in a manner which has won for him the gratitude and esteem of his friends and neighbours.” After his death, a Noah Robinson Memorial Window was dedicated in Swinton church in October, 1909. It was donated by Miss Howarth (presumably Robinson’s stepdaughter) and bears the words: “To the glory of God and in memory of Noah Robinson, born July 19th, 1826, departed this life, July 11th, 1907. Churchwarden of this Church 1871-1890 and Treasurer of St Peter’s Day and Sunday School from 1864 to 1898.” During the 1840s, a Mr T Robinson is names as the incumbent’s warden – perhaps his father, Thomas? This family link would explain his close association with the church. 7 6 January 2012 SWINTON LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLET 1 Some reflections There is much that can be learned from this story other than the career of one man. Firstly, we may note how the machinery of local government has changed over time to tackle the challenges that confront society. We have seen the arrangements change depending on the nature of the problem. The Poor Law Union was a federation of parishes which included Eccles Parish – and Swinton was just a small settlement within that parish. The Local Board was a response to public health concerns. Secondly, we can see a relationship between the local authority and economic growth. The pressure of growth – the increasing population of Swinton – meant that measures had to be taken to accommodate the influx of people into Swinton (generated by the growth of mills and mines – an issue not addressed in this paper). At the same time, the actions of the local authority in providing the necessary infrastructure clearly stimulated more growth. Finally, we can see how Swinton has changed over time. It changed from being at the margins of the Eccles Parish and administered through the Worsley Township, to developing its own local government. Initially it was separate from Pendlebury which was seen as part of Pendleton. Only from 1888 did Lancashire mean anything significant in terms of local government. Swinton was always part of the Salford Hundred. Swinton’s fate has always been enmeshed with its neighbouring communities and this is a reminder that Swinton is not a natural and eternal entity but one which has been in constant flux. The Swinton Community Committee asked that this pamphlet be produced to help preserve our heritage. The memorials to Noah Robinson exist within Swinton. I hope that this paper gives some meaning to the stones and glass which commemorate his service. Bibliography Eccles and Patricroft Journal, December 9, 1882, p8, cols 1-3 Eccles and Patricroft Journal, July 19, 1907, p10, col 1 Eccles and Patricroft JournaL, October 25, 1907, p5, col 3 Englander, D., (1998) Poverty and Poor Law Reform in 19th Century England, 1834-1914: From Chadwick to Booth, London and New York, Longman Fletcher, D., (1929) Swinton Church and Parish: Brief History, publisher unknown Heys, K., (1958) The Stained and Painted Glass Windows in the St Peter’s Parish Church, Swinton, publisher unknown Holland, P., (1914) Recollections of Old Swinton, Swinton, W. Pearson Midwinter, EC (1969) Social Administration in Lancashire 1830-1860, Manchester, MUP Robinson, N., (1901) Reminiscences (mimeograph in personal possession of author) Shaw, H., (1949) A Brief History of Christ Church and School, Pendlebury, publisher unknown Thornhill, W., (ed) (1971) The Growth and Reform of English Local Government, London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson Tupling, G. H., (1952) ‘The Turnpike Trusts of Lancashire’, in Memoirs and Proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, 94, session 1952-1953 Waterson, C., (2004) ‘Hon Guardian for Swinton Township’, in Lifetimes Link, Issue 14, November-May, 2004 7