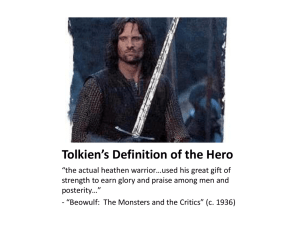

1. Intertextuality in Fantasy

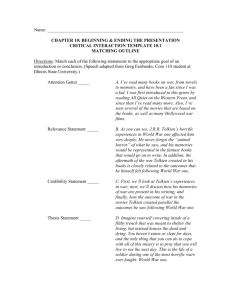

advertisement