operational guidelines for paediatric psychology services

advertisement

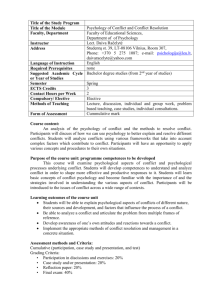

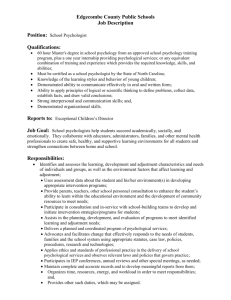

A Guide to Commissioning Paediatric Clinical Psychology Services in the UK Paediatric Psychology Network Briefing Paper September 2008 1 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. What is Paediatric Clinical Psychology? 4 3. What training and qualifications do paediatric clinical psychologists have? 6 4. What do paediatric clinical psychologists do? 8 5. How are paediatric clinical psychology services organised? 12 6. What evidence is there that paediatric clinical psychologists are effective? 16 7. Summary and Conclusions 18 8. References 19 Appendix – Examples of bids for paediatric clinical psychology posts 2 22 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document was written and produced by the Paediatric Psychology Network (PPN). The lead authors were Melinda Edwards and Penny Titman and we would like to acknowledge and thank the following: The PPN committee, Diane Melvin, Alisdair Duff, Clarissa Martin, Judith Houghton, Annie Mercer, Mandy Byron, Daniela Hearst, Sara O’Curry. 3 PROVISON OF PAEDIATRIC CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY SERVICES 1. INTRODUCTION This briefing paper provides a description of the role of a clinical psychologist working in paediatrics hereafter referred to as a ‘paediatric clinical psychologist’ and an overview of current paediatric clinical psychology services across the UK. It describes the context in which they have developed and the different organisational and management systems in which current services operate. The paper looks at the evidence base for psychological interventions in paediatric work, including the value added by these interventions and services. The aim of the document is to provide a guideline for psychologists developing such services, professional colleagues who use or wish to lobby for such services, trust boards and commissioners. 2. WHAT IS PAEDIATRIC CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY? Paediatric clinical psychology is a well established area of clinical psychology for children and young people with medical conditions and physical health needs. It has much in common with the field of clinical health psychology which has developed for adults and uses many of the same psychological theories, models and research evidence base (BPS, 2007a). In addition, it also draws on those areas of applied psychology (e.g. developmental and systemic) that are relevant to the particular needs of children, young people and their families, as well as the healthcare system providing services for them. Between 10 - 30% of children are affected in some way by chronic illness or physical health problems (Eiser, 1995). These conditions often have consequences for the emotional and social development of the young person. They also affect families and others involved in the child’s care. Whilst many children and families can be very resilient and cope well with the demands of a physical illness, children with a chronic illness are known to be at increased risk of developing psychological problems when compared to healthy children, with estimates of psychological difficulty ranging from 10% to 37% (Glazebrook et al, 2003, Meltzer et al, 2000, Kush & Campo, 1998). 4 Recent government guidelines on the development of services for children with physical health problems, for example the National Service Framework for Children in Hospital (DoH, 2004: Standard 6) recognise the importance of psychological input for children with chronic illness or disability: “Much can be done to help children and young people with long term conditions experience an ordinary life. A key element of this support should be good mental health input to maximise emotional well-being and prevent or minimise problems.” And standard 7 states that: “Attention to the mental health of the child, young person and their family should be an integral part of the children’s service, and not an afterthought…It is therefore essential for a hospital with a children’s service to ensure that staff have an understanding of how to assess and address the emotional well-being of children”. In “Making Every Young Person with Diabetes Matter” (DOH, 2005), the report notes: “Routine psychological support should be part of normal provision, rather than restricted to crisis management… services should consider the impact on families of diagnosis and adapting to life with diabetes and (staff) should be able to refer directly to specialist psychology that form part of the team” The importance of psychological input as part of a comprehensive medical treatment plan is also included in some of the National Institute for Clinical Effectiveness (NICE) guidelines, for example the guidelines for diabetes (NICE, 2004). These emphasise the importance of psychological aspects of care and recommended that routine psychological assessment should be included, in order to evaluate the effects of persistent hypoglycaemia and recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis on cognitive functioning. These documents recommend that psychological services should be considered as an integral part of children’s medical health care. This is because it is recognised that psychological input can have a direct impact on health outcomes by addressing problems such as adherence to treatment, as well as reducing psychological distress. Psychological interventions can often lead to a shorter stay in hospital and fewer medical appointments. In addition, addressing the child’s and family’s emotional needs alongside their physical health needs helps increase satisfaction with care. 5 3. WHAT TRAINING AND QUALIFICATIONS DO PAEDIATRIC CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGISTS HAVE? Clinical child psychology is the foundation for developing skills and expertise in the field of paediatric clinical psychology (Spirito et al, 2003). The vast majority of psychologists working in paediatric settings are clinical psychologists, with a very few health, academic and counselling psychologists. Paediatric clinical psychologists have an extended training (a minimum of 7 years). They have an undergraduate degree in psychology (3 years) and will have undertaken relevant experience as an assistant psychologist (typically 13 years) before being selected for post graduate training to doctoral level in applied clinical psychology (3 years). Their undergraduate psychology degree will have provided theoretical knowledge in psychological models and research methodologies based on an understanding of normal development. During postgraduate (doctoral level) training they will have gained clinical experience of working in a variety of interdisciplinary settings with a range of different patient groups and presenting problems, including working with children, adults and people with learning difficulties. The psychologist will have learned to apply evidence based practice across the life span, to be proficient in cognitive and neuropsychological assessment and to be able to use a variety of therapeutic techniques at an individual, group and systemic level. They will also have had extensive training in research methodology and will have completed a substantial research thesis. This comprehensive training ensures paediatric clinical psychologists have the necessary skills to work with complex psychological difficulties within multi cultural contexts and draw on a range of evidence based techniques. The report “Understanding ‘customer’ needs of clinical psychology services”, prepared for the Division of Clinical Psychology, BPS, surveyed commissioners, managers and clinicians and concluded that the unique contribution and skills of clinical psychologists were their broad knowledge base, range of approaches/ treatment modalities, skills in supervision, dealing with complex presentations and ability to work with teams, supporting service and organisational developments (Cate, 2007) After qualification, clinical psychologists working in paediatrics are required to undertake Continuing Professional Development (CPD) in order to continue to update their knowledge and skills base, and may have undertaken further training in specialist therapeutic techniques (e.g. family therapy) or areas of expertise (e.g. neuropsychology). The Paediatric Psychology Network (PPN), a network of the Faculty of Children and Young People within the British Psychological Society (BPS) organise a national annual study day contributing to the CPD of psychologists through a series of lectures and networking opportunities with national and international experts in this field. 6 Most psychology services will provide regular placements to doctoral clinical psychology training courses. This will involve 6 or 12 month placements, with trainees undertaking supervised clinical work for 6 sessions per week. These posts are funded by regional training centres. Some paediatric clinical psychology departments also employ assistant psychologists who have completed an undergraduate psychology degree. Assistant psychologists work under close supervision and are able to support the work of the paediatric clinical psychologists, for example by carrying out some structured assessments and developing research protocols. 7 4. WHAT DO PAEDIATRIC CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGISTS DO? Paediatric clinical psychologists work with children and young people with a medical illness and/or physical symptoms, their families and/or carers, including staff. They aim to reduce distress, promote optimal development, improve psychological well being and improve health outcomes for these young people and their carers. In order to achieve these goals, paediatric clinical psychologists work at several different levels: Direct clinical work with children, young people and their families referred because of identified concerns or those who are considered at risk of developing difficulties Consultation and joint work with other members of the multi-disciplinary health care team involved in the child’s care Conducting audit, research studies and evaluation Participating at a strategic, service or policy level within the wider system to improve care for children 4.1 Direct work with the child / young person and his or her family Paediatric clinical psychologists offer assessment and therapeutic work for children and families affected by physical illness problems. Some examples of these types of work include: Promoting adjustment and maximizing quality of life for children with chronic medical conditions Facilitating understanding and adaptation to the challenges of the child’s illness and treatment regime Assessment of psychological difficulties such as anxiety, depression, body image issues, and challenging behaviour. These difficulties may develop as a result of, or be exacerbated by, the child or young person’s medical condition and associated treatment demands Formulation of an appropriate psychological treatment plan drawing on a variety of theoretical models and evidence based practice Preparation for invasive or distressing procedures Symptom management techniques e.g. pain management techniques Promoting adherence to medical and allied medical treatment 8 Trauma work and bereavement support, including working with siblings and other family members Psychological and/or developmental assessments (psychometric tests, standardised assessments and individually designed assessments and interviews) Preparation and support for adolescent populations in the transition process to adult services as part of transitional care programmes Group work with children, young people or families e.g. psychoeducational workshops, support groups and user feedback groups Identification of co-morbid mental health needs which may require referral on to specialist Child and Adolescent Mental Health (CAMHS) services and risk assessment e.g. of self harm Proactive work with children and their family based on an agreed protocol e.g. for children undergoing organ or bone marrow transplant Preparation and support around reintegration into school and home following treatment and/or prolonged hospital admission 4.2 Consultation and joint work One of the advantages of the psychologist working as an integral part of the medical team is that this reduces the barriers between physical and psychological models of care and facilitates communication between team members. This helps to improve access to psychology services for children and families compared to having to refer outside of the health service to community child mental health services such as local CAMHS. Paediatric clinical psychologists work alongside the rest of the health care team in order to promote psychologically informed work by other members of the multidisciplinary team and therefore provide psychological input to a wider range of children and families. This can include consultation in multiprofessional ward rounds and psychosocial meetings, where the psychological needs of the child/family can be considered in conjunction with their medical needs. It may involve joint clinics and appointments with other professionals. It may also involve development of programmes undertaken with or by other staff (e.g. preparation for surgery, transition programmes). All clinical psychologists have training and experience in supervision, and can support the work of other members of the multi disciplinary team by providing case supervision of psychologically based work. They are also able to provide training for other members of the team to enable them to take on some work 9 which may be described as “low intensity” interventions (BPS, 2007b), for example managing procedural fear and distress and protocol based assessments. This enables more children and families to have access to psychological interventions, and is a cost effective way of delivering psychological care and making optimal use of psychology skills. The psychologist is often also used as a resource to facilitate team development and provide staff support within the clinical specialty team, for example facilitating support groups or providing support on an individual level. The aim of this work is to help manage and reduce staff stress but also to promote effective communication and teamwork amongst colleagues. Paediatric clinical psychologists can also be a valuable resource for community and education services around the child, providing support, consultation and training around psychosocial aspects of care for professionals and voluntary sector staff. 4.3 Audit, training and research Paediatric clinical psychologists have extensive experience of designing and carrying out research as part of their doctoral training. They are able to undertake, support and/or supervise both uni-professional and multiprofessional audit and research work. The psychologist may be directly involved in multidisciplinary research programmes (e.g. assessing long term impact of chronic health problems). Psychologists are well placed to advise medical teams on the use of good quality patient reported outcome measures as a primary outcome measure in medial research, as well as leading in the development of new robust illness-specific measures. Paediatric clinical psychologists provide teaching and training to other professional groups, as well as within psychology. For example, paediatric clinical psychologists contribute to the “Child in Mind” training scheme run by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, which provides basic training in understanding psychological difficulties for all doctors as part of their training in paediatrics and child health. 4.4 Strategic work and policy development Paediatric clinical psychologists contribute to the development of policy and guidelines at a local and national level. Examples of this include developing multidisciplinary guidelines, or protocols for specific clinical areas. These may be developed for the specific needs of the local population or applied more widely. For example, the Paediatric Psychology Network (PPN) has developed evidence based practice guidelines for managing invasive or distressing procedures and these have been disseminated nationally to relevant organisations including the Royal College of Nursing and The Royal College of Surgery. Paediatric clinical psychologists provide input and expertise to inform the development of NICE guidelines for specific areas of 10 child health, for example for childhood eczema, oncology and diabetes, and offer specialist advice to many national support groups and charities serving families with children with a range of physical health conditions. Paediatric clinical psychologists also work with their Trust’s executive teams to help interpret national standards at a local level, identify service needs and develop action plans to address unmet need. This may include contributing to local delivery plans with PCTs and regional commissioners. 11 5. HOW ARE PAEDIATRIC CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY SERVICES ORGANISED? The Paediatric Psychology Network (PPN), a network of the Faculty of Children and Young People within the British Psychological Society (BPS), is the professional group representing paediatric clinical psychology in this country and has over 170 members to date. The PPN aims to promote the development of paediatric clinical psychology, including professional practice, clinical governance, research and training. 5.1 Models of service provision The Paediatric Psychology Network completed a national review of paediatric services nationally in 2007/8, which included responses from 58 services, including those based in district hospitals, regional hospitals and in community services. The results indicate that psychology services are organised in a variety of ways, which can be categorized by the following models. Fig 1 - Service Model Paediatric Psychology / Integrated within health teams 5% 9% Mental Health Teams 7% CAMHS 79% Other The most prevalent model (79% of services) was that of a dedicated paediatric clinical psychology service, often based within a specialist Children’s Hospital/Department (e.g. Sheffield, Bristol, Great Ormond Street Hospital, Evelina Children’s Hospital, Yorkhill, Alder Hey, Leeds, Birmingham, Oxford). In this model, psychology sessions are integrated within one or more multi-disciplinary health teams across a variety of clinical specialties and in some instances, provide generic cover across all paediatric specialities or duty systems to cover all inpatient services 12 A further 7% of psychology services to paediatrics described themselves as being integrated within a broader multidisciplinary mental health service (e.g. North Middlesex, Manchester) for example in a psychiatry liaison service or integrated mental health service. These teams often have a mental health remit as well as working with children with a physical illness and include services such as risk assessment following self harm. 9% of clinical psychology services to paediatrics were based in Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) providing: (i) Locality based services for children with medical conditions as part of general CAMHS caseload (e.g Cambridgeshire) or with special clinics/dedicated sessions for these referrals (e.g Cystic Fibrosis service in Carshalton). (ii) Sessional input to local DGH as uniprofessional psychology service or part of a CAMHS Liaison service (e.g. Coventry, Staffordshire). 5% of clinical psychology input included community based palliative care/ life threatening illness teams (e.g. the Diana Teams) In terms of the location of services, 90% of regional/national services were hospital based, with the remaining 10% being specialist services that were based within their specialist teams outside of the hospital setting (e.g Bath Pain Management unit). 70% of psychology services to district hospitals were hospital based. Most regional services (95%) have either dedicated psychology sessions to particular specialities or a mixture of dedicated and generic sessions. In district hospitals and those served by liaison services, a predominant model of generic sessions was evident. Within current paediatric clinical psychology services, there were notable differences in organisation between district and larger regional hospitals. For example, 75% of psychology services in specialist/regional hospitals were both managed and funded by the hospital trust, whereas management was shared equally by CAMHS and hospital trusts in district hospitals. Funding for specialist areas of work came from both PCTs, hospital trusts and CAMHS but with much greater funding for generic work from CAMHS. To date there has not been a systematic evaluation of models of service provision. Feedback was elicited from the Heads of the psychology services who participated in the survey regarding their views about an optimal service model, and 86% supported a paediatric clinical psychology service which is hospital based, integrated within the multi disciplinary health team(s), and which has good access to a mental health service, either a psychiatry liaison team or CAMHS. Respondents reported that the distinct advantages of the predominant model include greater accessibility and responsiveness to referrals, effectiveness of 13 working relationships within the multi-disciplinary health team, opportunities for early intervention/ proactive work and joint research within the health teams. The few challenges reported with this model were more evident in services with fewer dedicated psychology sessions, and services that were based outside of the hospital. These included challenges in meeting clinical demands, funding difficulties and limited access to service developments. Also, challenges in maintaining effective links including difficulties referring on to local CAMHS (as cases often did not meet the threshold for referral criteria). In services with mixed management (acute health and mental health), there were reported challenges around clinical models and service/funding priorities reflecting management conflicts between acute health trust and CAMHS management. The Division of Clinical Psychology advises that service models should reflect the needs of the population served, local resources and structures and ensure patient safety through appropriate professional and clinical governance structures. All paediatric clinical psychologists are required to have appropriate professional supervision and it is important that professional management is effectively linked to service management to ensure resources are used as effectively and efficiently as possible. 5.2 Workforce planning Please refer to Appendix 1 for examples of bids made to secure psychology time within paediatrics, including identifying the number of sessions required. In order for a paediatric clinical psychologist to provide an effective, safe, evidence based service to a multi-disciplinary paediatric medical team, time is required for the following: Direct clinical work with children & families Consultation to and liaison with the health and social care systems around the child Activities relating to clinical governance (including audit & research) Continuous Professional Development In 2001, the BPS recommended a minimum of 2.0 wte clinical psychologists to input to paediatrics for a population of up to 250,000, but this figure did not take account of specialist or supra regional paediatric services. 14 The results of the PPN National Survey indicated considerable diversity in the clinical psychology provision within paediatric services. The range nationally was 0.2 – 18.3 wte psychology posts. Within specialist/regional children’s hospitals/departments a mean of 5.2 wte posts was reported and services to district general hospitals provided a mean of 1.0 wte posts. Some clinical specialties have developed their own recommendations regarding levels of psychology provision. For example, the Cystic Fibrosis Trust guidelines recommend 0.4 wte of a paediatric clinical psychologist per 50 patients. Within renal services, the BAPN (British Renal Unit Survey) recommends a minimum of 0.3 wte of psychology time (2 sessions for direct work and I session for consultation) per million population. Within Cleft services, the workforce recommendation is for 1 wte per 250,000 population (approx 150 births with Cleft lip and Palate). A Dutch working party of paediatricians and psychologists recommended 0.3wte psychology input for each paediatrician, based on a review of how many children were referred to paediatric clinical psychology services. 15 6. WHAT EVIDENCE IS THERE THAT PAEDIATRIC CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGISTS ARE EFFECTIVE? There is a good evidence base to support the clinical effectiveness of psychological interventions for a number of medical conditions and illnesses (Spirito and Kazak, 2006, Drotar et al, 2006). However, at present, there is less research on the cost effectiveness of these types of intervention. 6.1 Clinical Effectiveness A recent review by Spirito and Kazak (2006) summarises the evidence base for interventions in paediatric clinical psychology based on peer reviewed research papers and some examples from this are summarised here. Empirically supported treatments include the use of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for managing pain, including procedural pain (Powers, 1999) and recurrent abdominal pain (Janicke and Finney, 1999) and for managing symptoms with no known organic cause (Powers, 2005). CBT has also been found to be effective in a number of other interventions for children with a chronic illness e.g. for adolescents with cystic fibrosis (Hains et al, 1997) and for asthma. CBT is also effective in managing symptoms of anxiety or depression associated with chronic illness (Kaminsky et al, 2006). A combination of CBT and systemic techniques has been shown to be effective in reducing stress symptoms in cancer survivors and their parents (Kazak et al, 2004). Relaxation and self-hypnosis was shown to be effective in the management of pediatric headache (Holden, Deichmann & Levy, 1999). Behavioural therapy can be effective for some problems such as enuresis and encopresis (Mellon and McGrath, 2000, McGrath et al 2000) and for some feeding and eating problems (Benoit et al, 2001). Behavioural and multi component therapy has been shown to be of benefit in improving adherence to treatment (Lemanek et al, 2001). 6.2 Cost Effectiveness Research on psychological influences on health care use has shown that there is a link between psychological distress and increased use of health care. For example, Goldman and Owen (1994) showed that high levels of anxiety increased use of health care resources and therefore increased the cost of treatment. Cote et al (2003) showed that children with diabetes who have associated low mood have higher utilisation of health services. The psychological well being of medical patients has an impact on treatment and recovery, and therefore addressing these psychological factors may result in 16 reduced overall costs of treatment through shorter length of stay. In addition, psychological interventions for procedural fear or anxiety can enable a procedure to go ahead rather than be cancelled, helping to maximise efficient use of resources. At present, very few studies have quantified the cost of psychological intervention in order to identify any benefit in terms of medical cost offset. These benefits may include better use of health resources (such as higher levels of adherence, higher attendance at clinic appointments) resulting in lower medical costs through reduced complications in long term (Lemanek et al, 2001). Indirect cost benefits also include improved staff retention and a reduction in the number of days sickness reported when staff feel well supported in their work. Examples of paediatric studies which have included an evaluation of the medical offset cost of psychological intervention include a study of motivational techniques with adolescents with diabetes (Channon et al, 2007). A controlled trial of multisystemic therapy for diabetes demonstrated reduced inpatient admissions and significantly lower care costs for adolescents with poorly controlled diabetes (Ellis et al, 2005). Holmes, Walker, Llewellyn and Farrell (2007) showed that the cost of providing a transition care programme was covered by the cost savings made through fewer admissions to hospital. Within clinical health psychology focusing on adult patients, there is a more robust body of evidence from studies demonstrating cost effectiveness. These include Chiles, Lambert and Hatch (1999), who carried out a meta analysis of psychological interventions and estimated that the medical cost offset was around 20%. Another study looking at psychological assessment within plastic surgery, showed that effective assessment reduced the number of patients proceeding to surgery, resulting in cost savings that recouped the salary of a psychologist (Clarke et al, 2005). Studies have demonstrated the cost effectiveness of CBT in pain management in the adolescent and adult sickle cell population (Thomas, 2001) and interdisciplinary pain management (involving psychological therapy) in spinal pain treatment (Hatten, 2006). “Medical Crisis Counselling” (Koocher et al, 2001) has also been demonstrated to be cost effective in reducing distressing psychological symptoms accompanying a diagnosis of chronic illness (i.e. there were no increases in overall medical costs and some decreased mental health utilisation costs). Generally, psychological interventions can result in fewer cancelled or delayed medical procedures through universal management strategies for all children from extra help from play specialists (often supervised by psychologists) to direct intervention by psychologists for more complex cases. The cost benefits of this are evident to Trusts through greater through put and more funds from ‘payment by results’ 17 7. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS Paediatric clinical psychologists are uniquely positioned to provide a breadth of interventions along the multiple care pathways for children and young people with physical and health needs. They are able to work collaboratively alongside other health care providers taking a lead in promoting a psychologically informed perspective to improve the quality of care and health outcomes. Paediatric clinical psychology is a rapidly developing field of applied psychology within health care. This has resulted in improved integration of psychology within paediatric health service provision and strategic development of services which is integral to providing quality, holistic services for children in line with key DOH and NHS targets. The PPN can provide further information and can be contacted via the chair of the committee, Melinda Edwards : melinda.edwards@gstt.nhs.uk 18 8. REFERENCES Benoit, D., Madigan, S., Lecce, S., Shea, B. and Goldberg, S. (2001) Atypical maternal behaviours toward feeding disordered infants before and after intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22, 611-626. British Psychological Society (2003) Briefing paper: Child clinical psychologists working with children with medical conditions. Faculty for Children and Young People BPS, UK. British Psychological Society (2007a) Briefing paper No 27 Clinical Health Psychologists in the NHS. Division of Clinical Psychology, BPS, UK. British Psychological Society (2007b) New Ways of Working for Applied Psychologists NWWAP: The end of the beginning, BPS, UK. Cate, T. (2007). Understanding ‘customer’ needs of clinical psychology services. Division of clinical psychology, BPS, UK. Channon, S., Huws-Thomas, M., Rollnick, S., Hood, K., Cannings, R., Rogers, C. and Gregory, J. (2007). A multi-centre randomised controlled trial of motivational interviewing with adolescents with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 30, 1390-1395. Chiles, J., Lambert, M. and Hatch, A. (1999). The impact of psychological interventions on medical cost offset: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6, 204-220. Clarke, A., Lester, K.J., Withey, S.J. and Butler, P.E.M. (2005). A funding model for a psychological service to plastic and reconstructive surgery in UK practice. British Journal of Plastic Surgery, 58, 708-713. Cote, M., Mullins, L., Hartman, V., Hoff, A., Balderson, B., Chaney, J. and Domek, D. (2003). Psychosocial correlates of health care utilisation for Children and adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes mellitus. Children’s Health Care, 32, 1 – 16. Department of Health (2004) National Service Framework for Children – Standard for Hospital Services HMSO: London Eiser, C. (1995) Growing up with a Chronic Disease. Jessica Kingsley, London Ellis, D., Naar-King,S., Frey, M., Templin, T., Rowland, M. and Cakan, N.(2005). Multisystemic treatment of poorly controlled type 1 diabetes: Effects on medical resource utilisation. Jnl of Pediatric Psychology, 30, 656-666. Faculty for Children and Young People (2001) Guidelines for commissioning and purchasing child clinical psychology services. BPS. Finney, J., Eiley, A., Cataldo, M. (1991) Pediatric psychology in primary care: effects of brief targeted therapy on children’s medical care utilisation. Jnl Pediatric Psychology, 16, 447-461. 19 Glazebrook, C., Hollis, C., Heussler, H., Goodman, R. and Coates, L. (2003) Detecting emotional and behavioural problems in paediatric clinics. Child: Care, Health and Development, 29, 141-149 . Goldman, S.L., Owen, M.T. (1994). The impact of parental trait anxiety on the utilization of health care services in infancy: A prospective study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 19/3, 369-381. Hains, A., Davies, W., Berhens, D. and Biller, J. (1997). Cognitive behavioural interventions for adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Jnl of Pediatric Psychology, 22, 66987. Hatten, A.L., Gatchel, R, J., Polatin PB, and Stowell, A.W. (2006). A cost utility analysis of chronic spinal pain treatment outcomes: Converting SF-36 data into quality-adjusted life years. Clinical Journal Pain, 22, (8). Holden, W., Deichmann, M., and Levy, J. (1999) Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: Recurrent pediatric headache. Jnl of Pediatric Psychology, 24, 91-109. Holmes-Walker, D.J., Llewellyn, A.C. and Farrell, K. (2007). A transition care programme which improves diabetes control and reduces hospital admission rates in young adults with Type 1 diabetes aged 15-25 years. Diabetic Medicine, 24, 764769. Janicke, D. and Finney, J. (1999) Empirically supported treatment in pediatric psychology: recurrent abdominal pain. Jnl Pediatric Psychology, 26, 115-28. Kaminsky, L., Robertson M. and Dewey D. (2006). Psychological correlates of depression in children with recurrent abdominal pain Jnl Pediatric Psychology, 31, 956-966. Kazak, A., Aldefer, M., Steisland, R., Simms, S., Rourke, M. & Barakat, L. (2004) Treatment of posttraumatic stress symptoms in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families: a randomised clinical trial. Jnl of Family Psychology, 18, 407-415. Koocher, G.P., Curtis, E.K., Pollin, I.S & Palton, K.E (2001) Medical Crisis Counselling in a Health Maintenance Organisation: Preventative Intervention, Professional Psychology; Research and Practice. 32, 52-58. Kush, S. and Campo, J. (1998). Handbook of pediatric psychology and psychiatry. Allyn and Bacon, Needham Heights, MA. Lemanek, K., Kamps, J. and Chung, N. (2001) Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: Regimen adherence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 26, 25375. McGrath M.L., Mellon, M.W., Murphy L. (2000) Empirically Supported Treatments in Pediatric Psychology: Constipation and Encopresis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 25, 225-254. 20 Mellon, M.W. and McGrath, M.L. (2000) Empirically Supported Treatments in Pediatric Psychology: Nocturnal Enuresis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 25, 193214. Meltzer, H., Gatward, R., Goodman, R. and Ford, T. (2000) Mental health of Children and Adolescents in Great Britain. The Stationery Office, London. Paxton, R. and D’Netto, C. (2001) Guidance of Clinical Psychology workforce planning. Division of Clinical Psychology Information leaflet (6). The British Psychological Society. Powers, S. (2005) Behavioural and Cognitive behavioural interventions with pediatric populations. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 10, 65-77 Powers, S. (1999) Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology. Procedure-related pain. Jnl of Pediatric Psychology, 24, 131-145. Robins, P., Smith, S., Glutting, J. and Bishop, C. (2004) A randomised controlled trial of a cognitive behavioural family intervention for pediatric recurrent abdominal pain. Jnl of Pediatric Psychology, 30, 656-666. Spirito, A. and Kazak, A. (2006) Effective and Emerging treatments in pediatric psychology. New York: Oxford University Press. Thomas, V., Gruen, G. and Shu, S. (2001) Cognitive –Behavioural Therapy for the Management of Sickle Cell Disease Pain: Identification and Assessment of Costs. Ethnicity and Health 6 (1): 59-67. 21 Appendix Example bids for paediatric clinical psychology posts Clinical Psychology Input to Neurosurgery March 2004 Following extensive consultation, it has been agreed that a new post for the provision of clinical psychology to Neurosurgery will be established, supported by funding from the Neurosurgery Modernisation group. The table below lists the psychological needs of the children and families within main diagnostic groups with an estimate of clinical psychology time required. Diagnostic category No. children Psychological problems 1.Hydrocephalus 80 approx/year Intervention required impaired cognitive functioning and learning difficulties psychometric assessments & recommendations for special educational needs attention problems as above procedural anxiety related to repeated admissions for surgery desensitisation and coping strategies psychological adjustment to shunt coping strategies for child and parents difficulties with social interaction and peer relations behaviour problems social skills training, strategies for reintegration to school, liaison with local services cog/ behav management (CBT) for child and parents 22 Estimate of time needed 1 day/week Diagnostic category 2. Tumours 3. Epilepsy No. children 80 new cases/yr Psychological problems Intervention required procedural anxieties as above post surgical anxiety and associated behav. probs. related to short term effects of brain trauma coping strategies for child and family, liaison with local services intellectual and functional impairment associated with neurological deficits psychometric assessment with management advice behaviour and personality changes cognitive behavioural management for child and parents (CBT) depression and low selfesteem self –esteem training behavioural changes functional assessment and management adjustment to significant neurodevelop mental deficits rehabilitation coping strategies CBT for child, advice to parents, school behav. problems on ward and at home 23 Estimate of time needed 1 day/week 1 day/week Diagnostic category 4. Road traffic accidents No. children 1/ month Psychological problems intellectual changes as result of major brain trauma behaviour changes Intervention required psychometric assessment and advice, as above behav analysis/ CBT family work coping strategies consultation to schools Estimate of time needed 0.5 day/week family adaptation to damaged child 5. Others eg spinal surgery, cysts, abscesses, haemorrhage, congenital abnormalities reintegration to school cognitive/behav ioural changes adaptation to treatment and outcome as above as above Other activities: research and development 0.5 days/week psychosocial meeting 1 hr/week neuro-oncology meeting 1.5 hrs/week professional eg psychology dept meetings, supervision Total time: 5 days/week, 1.0 WTE Proposed Grading: Band 8b 24 0.5 days/week Bid for Paediatric Clinical Psychologist within Cardiac Services Role Project sponsor Project lead / manager Management Accountant sign-off Name Title Clinical Unit Manager Psychologist Management Accountant Statement of purpose: Brief description of what you are proposing The purpose of this investment proposal outline is to demonstrate the need for 1 Whole Time Equivalent (wte) Clinical Psychologist at Band 8b within Cardiology; the post would be 0.5 clinical, 0.5 staff support. Currently there is no staff support service and Cardiac Nursing sickness rate is running above the trust average; this has resulted in and has resulted in 1052 missed shifts since the start of the calendar year and, at the end of month 4, the Unit has spent £171,882 on Agency Nursing. Increasing the capacity of the service from 0.4 to 1.4 wte would provide significant improvements in three main areas; - the development of a staff support service in order to reduce stress and reduce the amount of short and long term sickness amongst the Cardiac Nursing Staff - provide greater equity to children and families who require the service - develop a psychosocial research strategy for the Cardiology to Service to improve the quality and capacity of cardiology research NHSProfessionals (NHSP) have been unable to fill all these shifts which has meant that either beds have been staffed with insufficient numbers, or closed. The large number of unfilled shifts has meant that beds have had to be closed and this has resulted in a decrease in throughput in the unit and a loss of income. Furthermore, the additional psychologist would contribute to effective decision making and unit policy development and enable greater provision of education to health professionals, both nationally and internationally. Strategic context: Please describe your proposal and how it meets the criteria that will be used to score you proposal. Where you have material to add against criteria, please use all the space you need under the heading. Scoring criteria for all other bids Staff Due to a long-term issue with high levels of sickness a stress survey was undertaken for the nursing staff by an external provider. The findings highlighted three areas which needed to be addressed; “I am unable to take sufficient breaks due to demands/pressure on me” “Different groups at work demand things from me that are hard to combine” “Workload is too much to obtain job satisfaction” 25 A number of away days were held with Band 7 nurses in order to address the issue in the short term. One of the goals of this exercise was to provide the Band 7 nurses with tools to address stress issues on the ward. The department is putting in another bid to increase nursing levels within the unit and the provision of a staff support service is a necessary development to ensure both that there is a suitable structure in place to support both existing and any new staff within the cardiothoracic unit. The provision of a staff-specific psychological services would address these issues, reduce both the sickness rate and hence reduce the amount of agency staff used, the number of unfilled shifts and the number of shifts which have been staffed under optimum levels of staffing. For the size group of the staff, above 150, it is necessary for 0.5 wte to be dedicated to setting up, providing and monitoring the service. Members of Paediatric Intensive Care Units are at risk of feeling burned out and disempowered as they are confronted with issues of life and death, reduced quality of life, children in pain and distress and their emotionally overwhelmed families as evidenced by studies (Gehring, Widmer, Banziger & Marti, 2002 and Meyer, De Maso & Koocher, 1996). The challenges posed necessitate supervision and specific training to increase individual coping and stress management as well as enhance team development, and can be provided by experienced clinical psychologist. The high levels of agency staffing is not only expensive but provides a degree of discontinuity in the quality of care offered and increases levels of stress amongst existing experienced staff. A major indirect impact of this has been the inability to staff beds which has impacted on Waiting List, 18 Week and Theatre Utilisation targets. Clinical The literature suggests that 25%-40% of children with CHD meet criteria for ‘caseness’ or clinically significant levels of anxiety or low mood. Anxiety and low mood, if unidentified/untreated can interfere with adherence to treatment and increase demand on services through increased preoccupation with symptoms. This is particularly true in cardiology where breathlessness, dizziness and palpitations mimic cardiac symptoms. In these cases patients need to be seen by a psychologist integrated within the cardiac multidisciplinary team. Research carried out by the current post-holder in the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Clinic, which saw 609 patients last year, demonstrated that 20%, 121 patients, of affected children showed clinically significant levels of anxiety and low mood at that time point. There is no clinical psychology provision for these patients. A conservative estimate is that 20% of children presenting in cardiology will have clinically significant levels of distress which may interfere with treatment, adjustment, adherence and exacerbate/mimic heart symptoms. Increasing our clinical psychologist service by 0.5 wte would mean that approximately 40% of patients who be able to be seen by the psychologist; currently there is only capacity to see less than 20% of patients. Although there would still be a large degree of unmet need this increase in capacity would allow more effective identification, prioritisation and treatment of psychological difficulties. Patients would be prioritised based on existing guidelines.This is a group of patients which have been identified as requiring psychological support, yet the sample size is representative of less than 1% of all patients seen within the cardiothoracic unit during 06/07. It is therefore difficult to quantify the level of unmet clinical need and therefore determine clinical priorities however, patients treated in the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Clinic would be prioritized by the new postholder. 26 Research The Unit Lead is keen to develop multidisciplinary research and psychosocial research. The current post holder has insufficient time to coordinate this or increase the capacity and profile of the multidisciplinary research. This is a particular shortfall on a unit where there are unique treatments and opportunities for novel research with new patient groups and existing patient groups Outline of demand and capacity issues. There is currently no support service for the nursing staff and this need has been identified through the staff stress survey and a staff questionnaire carried out by the current postholder and ECMO Coordinator has highlighted that staff are keen to have regular support. The current capacity of the psychological service for children/families is 0.4 wte post which covers Cardiac Critical Care, Ladybird Ward, ECMO and Cardiac Outpatients with waiting times varying between 2 to 12 weeks. The current level of provision means that the wards have no cover for 5 days of the week and there is no cover when the postholder is on annual leave / study days. A recent audit of clinical psychology provision to cardiology found that there is a capacity for 117 new cases (261 appointments), which is less than 1% of cardiology patients (7315 for 06/07). In addition, the majority of referrals were found to have come from 2 consultants. With the Psychologist able to provide a service to fewer than 1% of children presenting, there is a significant risk that many children’s needs are not being met. Another clinical psychologist would mean that another 195 appointments would be available meaning that 456 appointments would be available which would reduce the waiting list to 7 weeks. The existing 0.4 wte post covers Cardiac Critical Care, Ladybird, ECMO and Cardiac Outpatients. Consequently the waiting list for psychology is significantly affected by the rate of referrals, with waiting times varying from 2 weeks to 12 weeks. 0.4 wte means that the wards have no cover for 5 days of the week and that inpatients/families in crisis can wait up to 5 days to be seen and there is no cover when the psychologist is on annual leave. 27 Financial Summary (a completed breakdown should be included with the proposal) Year Capital Costs Revenue Costs Non-recurring revenue costs Income expected from related activity Planned revenue savings First Year Recurring £31,317 £62,635 £58,930.97 Budget breakdown: Please show the broad cost headings for the investment. Staff Costs Equipment costs Maintenance Costs Consumables Costs Training Costs Installation Costs Please ensure VAT is added to the costing, including for Medical Equipment bids. Mid point of Band 8b (Pay point 41) is £62,635 including High Cost Area Allowance & on cost. Therefore, allowing for recruitment, 6 months of 1.0 wte Band 8b is £31,317 Dependant on timely recruitment we estimate that it would take 2 months for the service to be set up – at this moment it is difficult to quantify the savings which could be expected within the first year. Outcomes Brief outline of how you will demonstrate that the investment has generated the benefits that you intended, for example details of performance indicators, satisfaction measurement, evidence of clinical effectiveness, reduced risks. Please tell us, where appropriate, why it isn’t possible to demonstrate clearly the benefits from an investment The efficacy of clinical supervision and its effect on job satisfaction and quality of patient care has been shown to be enhanced by nursing staff being given both supervisor and supervisee roles as well as training in clinical supervision (Hyrkas, Appelqvist-Schmidlechner and Haataja, 2006.) Setting up such a system would require some further evaluation of the needs of the target staff group as the supervision needs of staff have been found to vary with grade (Butterworth et al., 1999) and experience (Hyrkas et al., 2006.) In addition, a system of assessing the quality and effectiveness of the staff support provided would need to be built in from the start and continually monitored, since the effectiveness of clinical supervision and staff satisfaction with supervision has been shown to increase after 2-5 years (Butterworth et al., 1999.) The staff support strategy will be evaluated with pre and post measures of staff stress, job satisfaction and patient satisfaction using standardised measures as well as specific goal setting by staff. It is therefore difficult to quantify the impact of the service but it estimated that spend on Agency Nursing will decrease by 20%. This would result in a £58,930.97 saving annually, based on projections from this year’s spend on agency staffing. As this is based on the staff support aspect of the post this is the saving on 0.5 of the post (i.e. £31,355.) The clinical part of the position would be providing indirect benefit to the unit in terms of throughput; this is difficult to quantify and linked more closely with the Cardiothoracic Unit’s 28 bid to increase staffing and throughput. The part of their role the postholder will be expected to undertake a needs assessment, put in place appropriate systems dependent upon the results of the needs assessment and undertake an ongoing evaluation this process Clinical Outcomes / benefits for patients: The early identification and treatment of mental health issues that interfere with or mimic cardiac symptoms will ensure that psychological and developmental issues are taken into consideration in multidisciplinary team and family decision making. This will enable the supporting of patients and families who have significant difficulty adjusting post-operatively (e.g. reactive depression following ICD insertion, health anxiety following cardiac surgery, reduced function or mobility that cannot be explained by the objective health status) Outcomes and performance management will be measured through Board/Monitoring reports: Monitor the number and diagnosis of patients seen by a psychologist Sickness and absence monitoring Activity targets Income target Theatre utilisation 29