370012MyersMod_LG_28

advertisement

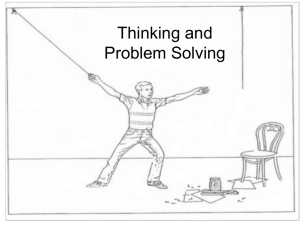

MODULE 28 PREVIEW Concepts, the building blocks of thinking, simplify the world by organizing it into a hierarchy of categories. Concepts are often formed around prototypes, or the best examples of a category. When faced with a novel situation for which no well-learned response will do, we may use problemsolving strategies such as trial and error, algorithms, and rule-of-thumb heuristics. Obstacles to successful problem solving include the confirmation bias, mental set, and functional fixedness. Heuristics provide efficient, but occasionally misleading, guides for making quick decisions. Overconfidence, framing, belief bias, and belief perseverance further reveal our capacity for error. Still, human cognition is remarkably efficient and adaptive. With experience we grow adept at making quick, shrewd judgments. Studies of artificial intelligence reveal the strengths of the human mind. Although the computer shines on certain memory tasks and in making decisions using specified rules, it is dwarfed by the brain’s wide range of abilities and capacity for processing unrelated information simultaneously—although computer systems have been designed to mimic the brain’s interconnected neural units. GENERAL INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES 1. To explore how we construct concepts and solve problems. 2. To discuss obstacles to problem solving. 3. To explore how we make decisions and form judgments, and to present computer models of human thought processes. MODULE GUIDE Introductory Exercise: Fact or Falsehood? Concepts 1. Describe the nature of concepts and the role of prototypes in concept formation. Cognitive psychologists study cognition, which is the mental activity associated with processing, understanding, and communicating knowledge. To think about the countless events, objects, and people in our world, we organize them into mental groupings called concepts. To simplify things further, we organize concepts into hierarchies. Although we form some concepts by definition, more often we form them by developing prototypes—a best example of a particular category. The more closely objects match our prototype of a concept, the more readily we recognize them as examples of a concept. Exercises: The Limits of Human Intuition; Cognitive Complexity Project: Prototypes and Concept Formation Video: Discovering Psychology:Cognitive Processes Solving Problems 2. Discuss how we use trial and error, algorithms, heuristics, and insight to solve problems. We approach some problems through trial and error, attempting various solutions until stumbling upon one that works. For other problems we may follow a methodical rule or step-by-step procedure called an algorithm. Because algorithms can be laborious, we often rely instead on simple rule-of-thumb strategies called heuristics. Speedier than algorithms, heuristics are also more error-prone. Sometimes, however, we are unaware of using any problem-solving strategy; the answer just comes to us—as an insight. Lecture: Jokes, Riddles, and Insight Exercises: Dice Games to Demonstrate Problem Solving; The “Aha!” Experience Projects: Problem-Solving Strategies; The Tower of Hanoi Problem 3. Describe how the confirmation bias and fixation can interfere with effective problem solving. A major obstacle to problem solving is our eagerness to search for information that confirms our ideas, a phenomenon known as confirmation bias. This can mean that once people form a wrong idea, they will not budge from their illogic. Exercise: Confirmation Bias Lecture: The Confirmation Bias and Social Judgments Another obstacle to problem solving is fixation—the inability to see a problem from a fresh perspective. The tendency to repeat solutions that have worked in the past is a type of fixation called mental set. It may interfere with our taking a fresh approach when faced with problems that demand an entirely new solution. Our tendency to perceive the functions of objects as fixed and unchanging is called functional fixedness. Perceiving and relating familiar things in new ways is an important aspect of creative problem solving. Exercises: Demonstrating Mental Set; Functional Fixedness Film: Creative Problem Solving Transparencies: 120 The Four-Card Problem; 121 The Candle Mounting Problem and Its Solution; 122 The Nine-Dot Problem and Its Solutions Making Decisions and Forming Judgments 4. Explain how the representativeness and availability heuristics influence our judgments. The representativeness heuristic is a rule of thumb in which we judge the likelihood of things in terms of how well they seem to represent particular prototypes. If something matches our mental representation of a category, that fact usually overrides other considerations of statistics or logic. The availability heuristic operates when we base our judgments on the availability of information in our memories. If instances of an event come to mind readily, we presume such events are common. Although both heuristics enable us to make snap judgments, they can also lead us to ignore other relevant information and thus to err. Exercises: The Representativeness Heuristic; The Base-Rate Fallacy; The Availability Heuristic PsychSim:Rational Thinking Videos: Discovering Psychology: Judgment and Decision Making; Are We Scaring Ourselves to Death? 5. Describe the effects that overconfidence and framing can have on our judgments and decisions. Overconfidence, the tendency to overestimate the accuracy of our knowledge and judgments, can have adaptive value. People who err on the side of overconfidence live more happily and find it easier to make tough decisions. At the same time, failing to appreciate one’s potential for error when making military, economic, or political judgments can have devastating consequences. The same issue presented in two different but logically equivalent ways can elicit quite different answers. This framing effect suggests that our judgments and decisions may not be well reasoned, and that those who understand the power of framing can use it to influence important decisions—for example, by wording survey questions to support or reject a particular viewpoint. Exercises: The Overconfidence Phenomenon; Framing Decisions Lecture: The Disjunction Fallacy or Irrational Prudence Belief Bias 6. Discuss how our beliefs distort logical reasoning, and describe the belief perseverance phenomenon. We show a belief bias in our reasoning, accepting as more logical those conclusions that agree with our beliefs. Similarly, we more easily see the illogic of conclusions that run counter to our beliefs. We also exhibit belief perseverance, clinging to our ideas in the face of contrary evidence because the explanation we accepted as valid lingers in our minds. Once beliefs are formed and justified, it takes more compelling evidence to change them than it did to create them. Lecture: Belief Bias Simulating Thinking: Artificial Intelligence 7. Describe artificial intelligence, and contrast the human mind and the computer as information processors. Artificial intelligence (AI) is the science of designing computer systems to perform operations that mimic human thinking and do “intelligent things.” The most notable AI successes focus computer capacities for memory and precise logic on specific tasks, such as playing chess and diagnosing illnesses. In those areas where humans seem to have most difficulty—manipulating huge amounts of numerical data, retrieving detailed information from memory, making decisions using specified rules— the computer shines. But even the most sophisticated computers are dwarfed by the most ordinary of human mental abilities—recognizing a face, distinguishing a cat from a dog, exercising common sense. For now, the brain’s capacity for processing unrelated information simultaneously and the wide range of its abilities outstrip those of the computer. But hopes grow that a new generation of computer neural networks—computer systems designed to mimic the brain’s interconnected neural networks—will produce more humanlike capabilities. The most exciting feature of artificial neural networks is their capacity to learn from experience as some interconnections strengthen and others weaken. Lecture: The Computer and Common Sense Video: Segment 28 of the Scientific American Frontiers Series, 2nd ed.