Trash or Treasure - Sweet Briar College

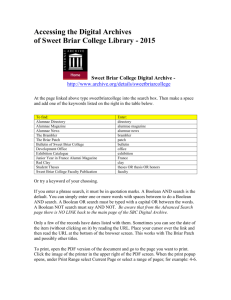

advertisement

Trash or Treasure by Emily Poore Introduction Archaeology is the study of any culture by the analysis of its physical remains in order to provide more information about a time and place in the past. Archaeology provides another dimension to the conventional understanding of our past. The physical evidence that is part of this exhibit differs from the traditional written documents used to create history. Written documents reflect the ideas, beliefs, and activities of the minority of literate individuals who left behind a written record. These ideas and beliefs are not explicit and require the interpretation of historians. History, then, is a modern construction of the past. Large segments of the population and the day-to-day events of a group are often left out or ignored in an approach based only on written documents. In contrast, archaeological remains include the actual objects used by individuals within a community. Within a collection of physical objects, all of the residents of a community have a voice, whether or not they had the ability or opportunity to leave written records. By uncovering the physical objects of a culture, archaeologists seek to construct narratives about their history that is often left unspoken in written documents. Within the discipline of archaeology, the trash of one generation becomes, in later generations, the treasure that sheds light on the events of the past. The objects in this exhibit are literally the trash from Sweet Briar College during its first decades. Out of the ground and cleaned, these artifacts are no longer trash, but the physical remains of an earlier culture and the basis from which historical narratives can be constructed. The process of exploring archaeology also brings the understanding that the physical objects important to us might be used by future generations to understand today’s society. Sweet Briar Excavation The Sweet Briar excavation was led by Anthropology Professor Claudia Chang in spring 1985 as a student exercise into the methodology of archaeological fieldwork. Students excavated a wooded area behind Woodland Road in four units with three vertical levels to an ultimate depth of sixty centimeters. The College used trash dumps around campus, similar to the one excavated, until the 1960s. Using excavated glass Coca-Cola bottles that bear a patent date of November 1915, a more specific date for the disposal of this group of artifacts can be formed. The bottle design patented by the Coca-Cola Company in 1915 was in use from 1916 to 1923, when it was replaced by a newer design.1 Given that the Coca-Cola bottles found in the excavation bear the 1915 patent date, it is possible to date the use of this particular trash dump to roughly the period between 1916 and 1923. Information about the manufacture of various excavated ceramics support this date, with companies in business from the 1880s through the first three decades of the 20 th century. 1 Orser & Fagan, Historical Archaeology (New York: Harper Collins College Publishers, 1995) 77. This examination of the artifacts, therefore, will focus on this early period in the College’s history. The objects have been organized into seven categories: academic, Sweet Briar issue (objects provided by the College), personal items, food and drink, health and beauty, beyond Sweet Briar, and parts of the Sweet Briar utopia. In addition to the artifacts, College course catalogs, student handbooks, bulletins to parents, and newspaper articles from the period will provide a written perspective on the period. Student course catalogs and handbooks were published by the College because they portrayed the image of Sweet Briar College that was approved by the faculty and administration. The reality of day-to-day life at Sweet Briar, however, is not clear in these documents. The collective ideal expressed in today’s brochures and course catalogs is often different from the actuality of everyday life for an individual at Sweet Briar, and the same is true of life at Sweet Briar in the first decades of the College. Objects that are used and discarded document all of life in a community, not only the representations chosen for publication. This examination of Sweet Briar artifacts will present the objects, in addition to traditional written documents, as another source of information about the early years of the College. Academic Sweet Briar College was incorporated in 1901 through the bequest in the will of Indiana Fletcher Williams’ to establish “a school or seminary for the education of . . . young women.”2 Williams desired a school to be established in the memory of her daughter, Daisy, that would educate women to become “useful members of society.”3 The College’s first board of directors spent the next five years building the College and preparing for the arrival of the first students in 1906. The College experienced a great deal of growth and change in its first decade; enrollment increased, new faculty were hired, and new buildings were added to the campus. By 1916, the College had graduated six classes of women and was preparing to greet Sweet Briar’s second president, Emilie Watts McVea.4 The College’s academic environment also experienced changes in the early decades, although not as drastic as in other areas of College life. The early directors of the College viewed an education in the classics as the most appropriate way to prepare women to become useful members of society. The course catalogs, or year books, from the first decades of the College detail the curriculum at Sweet Briar during this time. Admission requirements in 1915, for example, required candidates to have completed a total of 15 units of year-long study in English, mathematics, history, French or German, and Latin. The most intensive study was required of Latin, where four units were desired versus just three of English.5 A bachelor of arts was the only degree offered in 1915 in six courses of study; English, modern languages, ancient languages, history and economics, math and physics, and science.6 By 1925, the College had grown enough to support both a bachelor of arts and a bachelor of science degree, with new majors in philosophy and psychology, biology, chemistry, and social science.7 2 Martha Stohlman, The Story of Sweet Briar College (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956) 39. Stohlman, The Story of Sweet Briar, 39. 4 Stohlman, The Story of Sweet Briar, 128. 5 The Tenth Year Book of Sweet Briar College 1915-1916, 11. 6 1915-1916 Year Book, 30. 7 Catalogue of Sweet Briar College 1925-1926, 41-42. 3 In the early 20th century, an emphasis on the classics was not unusual in the education of young people, male and female. The appearance of courses in the sciences, however, is more surprising during an era when a woman’s place was still largely considered to be in the home. Although the number of professional women was increasing during the first decades of the 20th century, their number in the general population of women was still small. The presence of scientific equipment such as test tubes and glass tubing in the uncovered artifacts demonstrates that early Sweet Briar students were not only learning the theory or history of chemistry and biology, but also participating in laboratory experiments. The early administrators of the College, therefore, were serious about preparing women to become useful members of an increasingly modern and scientific society. Although courses in domestic science were offered at Sweet Briar during this period, disciplines beyond the traditional woman’s sphere of home and children were also included in the curriculum established by the College in its first decades. The presence of a handmade apple among the excavated artifacts suggests the merit given to art in the early College curriculum. Art curriculums in the early part of this century focused on drawing and painting, not the sculpture techniques that would have produced this apple. Although this apple was not produced as part of the art curriculum at Sweet Briar, it demonstrates that a member of the community enjoyed something with aesthetic as well as functional qualities. The 1915 catalog offers both historical and studio art classes as electives, and advertises an art studio among the facilities available for students.8 These references to an art program are also in the 1925 catalog, but despite the increased number of courses of study, art still does not appear as a major. In the early decades of the College, art was an acceptable and encouraged elective, but not considered the basis for four years of study. The first directors of Sweet Briar College sought to establish a school where young women could be educated to meet the needs of a larger society. This task was taken seriously, and a curriculum was formed that promoted the classics and science. Sweet Briar’s curriculum followed the lead of top women’s colleges founded in the nineteenth century, most notably the Seven Sisters (Smith, Mount Holyoke, Barnard, Vassar, Radcliffe, Wellesley, and Bryn Mawr), in educating young women in math and science as well as foreign languages, literature, and history. This curriculum adequately prepared two of the five members of the Class of 1910 to pursue graduate work in their field after graduation from Sweet Briar.9 Sweet Briar Issue In addition to providing a fine academic education for the students willing to believe in a young, small school, the early administrators also sought to build a self-sufficient community. Sweet Briar’s country location necessitated this to a degree. Faculty lived on campus from the very beginning, first in Sweet Briar House, later in apartments and houses built on Elijah Road and Faculty Row. Students, with the exception of a small number of day students, all lived on campus. Faculty and students alike dined in the Refectory on food grown in the College’s orchards or farm field, accompanied by milk and cream from the 8 9 1915-1916 Year Book, 64. Alix Ingber ed., Tradition and Change: A Sweet Briar Anthology (Sweet Briar College, Summer 1998) 6. dairy. The first board of directors planned a farm to provide the College with flour, meat, vegetables, and milk.10 The orchards and the dairy were the most successful, and most enjoyed, of these endeavors. The residents of Sweet Briar not only lived and worked in a community, but also found time to play, with frequent theatrical performances, class rivalries, and athletic contests. Train service and a road between Lynchburg and Charlottesville linked the College to the rest of Virginia, but the College was still isolated from external facilities capable of providing a sufficient amount of fresh food and electricity for a growing community. Sweet Briar built its own power plant to provide electricity for the College. Polly Bissell ’17 recalled that “ lights blinked at 10:20 p.m., and were turned off at the power plant at 10:30.”11 The College not only provided the light bulbs found in the excavated trash dumps, but also the electricity that resulted in light. Personal Items The College provided many other necessities of life to its residents. In 1918, students were asked to bring only towels and an extra blanket to furnish their rooms. The College provided furniture, rugs, bed linens, and additional supplies could be purchased in Lynchburg.12 Students generally arrived on campus by train with their belongings packed in trunks. The College ensured that students needed to pack only clothing and a few personal items, quite different from the carloads seen when students move in today. Beyond the dresses, skirts, bathing suits, raincoats, and sensible shoes suggested as necessary attire for a new Sweet Briar student13, most women brought additional items from home. These items are classified as personal belongings because they appear in limited numbers among the excavated artifacts. Objects that were used by all the members of the community, china from the Refectory for example, are more numerous. Individual pieces of china, however, that appear without a mate in the excavated trash dumps are more likely the result of a personal place setting, either used in the private homes of faculty and staff or in the dormitory rooms of students. Like today, students during the 1910s and 1920s found time for a cup of tea or drink of water in their room in the evening, and a teacup would come in handy for this purpose. These individual pieces of china come in a variety of patterns, from a bright yellow glaze to a hand-painted flower pattern. A brightly decorated teacup or an elegantly painted cup was a small and convenient way for a student to demonstrate her individuality in a room filled with institutional furniture. The leisure activities of the residents of the early College can also be seen from excavated personal items. A metal kazoo was uncovered, perhaps used to provide music for the frequent theatrical productions or at step singing. Step singing began in 1922, when seniors took their honored position on the refectory steps on Sunday afternoons, while the other classes formed a square in front of them and took turns singing.14 Although some songs were popular tunes or old favorites, from the very beginning Sweet Briar students 10 Stohlman, History of Sweet Briar, 55. Ingber ed., Tradition and Change, 7. 12 1918-1919 Student Handbook, 49. 13 Ingber ed., Tradition and Change, 43. 14 Stohlman, The Story of Sweet Briar, 141. 11 modified the words to hold a particular appeal to the community. A kazoo, then, may have been one way to provide a tune for these impromptu gatherings before the convenience of battery-powered cassette players used today. Food & Drink The Refectory, now remodeled into the Pannell Art Gallery, was the location of the common meals provided for the community by the College. Students and faculty dined together at meals served by waitresses employed by the College. Punctuality was important, as “the Refectory door was locked ten minutes after the bell rang for meals.” 15 Even the College president was present at these meals, leading a silent grace before the meal was served. Students who were unable to make it to meals because of illness could have a meal delivered to their rooms for $ .25. If a student was too hungry to wait until mealtime, bread, butter, jam, and fruit was available in the Refectory an hour before and after meals for a nominal fee.16 Mealtime, however, was not the only opportunity to eat at Sweet Briar. A number of food containers were among the excavated artifacts. The size of these containers, for example, a sardine can, are small enough to suggest a single serving, not the large institutional size that must have been used for meals served in the Refectory. If the College was cooking for both students and faculty, these containers suggest that someone was snacking between meals. From the archaeological evidence, sardines and canned preserves must have been the snacks of choice at Sweet Briar in the 1910s and 1920s. Mason jars and their milk glass lids were found in the excavated trash dumps and could have contained any number of canned fruits or vegetables when full. Another popular source of between-meal snacks on campus was the Boxwood Inn. A teahouse started by the faculty in 1907 was housed in the little cottage beside Sweet Briar House to provide students with a place to gather for food, drink, and conversation two afternoons a week.17 In 1922, the Boxwood Inn, now the Alumnae House, was built to provide a permanent home for the teahouse and accommodations for overnight visitors. 18 The Boxwood Inn was a favorite gathering spot on campus, attracting those in search of desserts or Coca-Cola, which was an extremely popular refreshment on campus. A number of bottles and fragments were found in the excavation, in addition to numerous references to five-cent Cokes in personal accounts of alumnae. Coca-Cola was so popular at Sweet Briar that during World War II a sugar ration limited the amount of Coke available to one cup per day per student. None would be sold during the morning, and at night only “if the day’s ration is not exhausted.”19 A plea was made in The Sweet Briar News for students to cooperate with the management of the Inn, who were doing their “best under a war-time ration to keep us satisfied.”20 During the 1910s and 1920s, Coke was sold in glass bottles, and it is these bottles, and other soda bottles like them, that demonstrate the frequency with which students gathered at the Inn for a drink. 15 Ingber ed., Tradition and Change, 7. 1925-1926 Student’s Handbook, 94. 17 Stohlman, The Story of Sweet Briar, 106. 18 Stohlman, The Story of Sweet Briar, 145. 19 Ingber ed., Tradition and Change, 46. 20 Ingber ed., Tradition and Change, 46. 16 Health & Beauty The greatest number of glass bottles uncovered contained health and beauty products. The items used for health purposes were basic in nature. Several fragments of cobalt-blue Milk of Magnesia glass bottles were found. Milk of Magnesia was a common cure-all for stomach complaints and was probably administered by Dr. Mary Harley, the College physician and hygiene professor from 1906 until her retirement in 1935. According to students, castor oil was another favorite remedy administered by Dr. Harley to any visitor to the infirmary.21 Other medicine bottles were excavated, but it is unknown exactly what they originally contained. These bottles bear markings on their sides for measuring, and often the name of the drug company is part of the bottle’s design. Small, brown glass bottles were also found, one with an eyedropper still in the neck of the bottle. These bottles do not bear the same markings as the larger medicine bottles, and the eyedropper would suggest that these fluids were dispensed in much smaller quantities. One rubber stopper was found in the excavated trash dump and it is likely that all these bottles used such stoppers. Only one toothbrush was found among the excavated artifacts, but many Listerine bottles were found. With replaceable bristles, the concept of replacing entire toothbrushes regularly was not common. The power of Listerine to fight bad breath and kill germs, however, was widely accepted. In 1914, Listerine became the first mouthwash available over-the-counter, which explains its dominance in the archaeological record.22 More numerous than medicinal bottles, however, are the bottles that contained some form of beauty product. Cosmetic compacts, nail polish, cold cream, perfume, and talcum powder bottles were all found in the excavated trash pit. Many of these bottles are decorative and ornate, while some, especially those containing cold creams, are more functional. Popular brands included Pond’s cold cream, Carbona perfume, Cutex nail polish, Coty perfume, and A.S. Hinds cream. Despite the single-sex atmosphere, early students were still concerned about their appearance. They used a variety of beauty products; items they probably believed would improve their appearance. Even if there were not men to impress most days of the week, men from neighboring colleges were invited for regular Saturday evening dances.23 Beyond Sweet Briar Many of these beauty products were manufactured in other states or countries. For example, one popular cream bottle was A.S. Hinds Honey and Almond Cream manufactured in Portland, Maine, from 1870 to 1925.24 One perfume bottle is marked as being made in France. These bottles demonstrate the influence of the wider world on Sweet Briar. Students and faculty came from variety of places; in 1906, the first 51 students were from twelve states 25, and that number grew as Sweet Briar grew. The number of A.S. Hinds bottles excavated make it unlikely that a student brought them directly from Maine. Instead, 21 Stohlman, The Story of Sweet Briar, 176. Http://www.oral-care.com/listerine.html, 11/19/98. 23 Ingber ed., Tradition and Change, 6. 24 Julian Harrison Toulouse, Bottle Makers and Their Marks (Camden, NJ: Thomas Nelson, Inc., 1971) 54. 25 Stohlman, The Story of Sweet Briar, 77. 22 it would seem that this particular cream was available for purchase in Amherst or Lynchburg, where all Sweet Briar students would have access to it. National and international news events also influenced Sweet Briar. World War I was one of the first major international events during the College’s life. Life continued as usual at the College, with students rallying around the war by organizing a Red Cross, rolling bandages, and knitting socks and sweaters for American soldiers.26 Emilie Watts McVea, the president of the College, announced an end to the war on November 9, 1918. Sweet Briar, however, still lacked radio reception, and it was four days later that the College learned that peace was actually signed on November 11, 1918.27 Despite its isolation, the College community was not content to remain separate from the country and the world. By 1920, students attended Sweet Briar from 38 states. 28 The College also set its sights internationally, and in 1919 the first international student was welcomed from France. A year later another foreign student from Serbia joined the Sweet Briar community.29 Sweet Briar students, however, did not venture internationally as part of the curriculum until 1930, when the first students spent a year studying in France. Although there was not a study abroad program at the College until 1930, there were objects found in the excavated trash dumps that suggest an international consciousness. A plate made in Germany and decorated with Dutch style houses could have been a souvenir from a European tour, or perhaps an object purchased in this country to remind the owner of a trip or a dream to travel. Likewise, a Chinese coin could be a souvenir or a gift from someone who had been travelling. Sweet Briar Utopia Among the excavated objects were several items that bring to mind some of Sweet Briar’s unique characteristics. One of these artifacts is a piece of a balustrade footing, part of the College’s architecture. Ralph Adams Cram, one of America’s most distinguished architects, designed the campus. Cram’s original 1902 plan included a classical arrangement of 17 Georgian Revival brick buildings around a quadrangle with parterres and formal plantings, fountains, and pools. The College’s board of directors, experiencing a shortage of funds and a preference for a simpler layout, began the College with just four of Cram’s original buildings, Gray, Academic (Benedict), Carson, and the Refectory (Pannell). Throughout the years Cram served as the College’s architect, more buildings were added and changes were made to the original plan. Although later buildings did not always conform to Cram’s original plan, his plan is still the framework underlying the Sweet Briar College Campus and provides Sweet Briar with its essential character today. Cram’s architecture is a source of pride for the College and is viewed as a distinguishing feature of Sweet Briar. Another distinguishing feature of the College today is its country location and its horseback riding program. One of the artifacts uncovered in the trash pits was a horse or mule shoe. The shoe is too large for a typical riding horse, but still brings to mind images of 26 Ingber ed., Tradition and Change, 8. Ingber ed., Tradition and Change, 8. 28 Stohlman, The Story of Sweet Briar, 147. 29 Stohlman, The Story of Sweet Briar, 142, 147. 27 the riding program that draws students to Sweet Briar from around the country today. The riding program was popular from the early days of the College when written consent from parents was necessary for students to participate. Thanksgiving was celebrated with a morning fox hunt, beginning with the very first Thanksgiving celebrated at Sweet Briar College in 1906. Naturally, during the first years of the College, horses were used more often for practical reasons than for recreation. Horse and buggies provided transportation until automobiles became more prevalent, and the animal that wore the shoe in this exhibit probably worked in the fields that were still being farmed on Sweet Briar’s campus. Finally, the dairy, which closed in 1994, still holds a special place even among students who never tasted fresh Sweet Briar Dairy milk. The College provided milk and cream for the community from the very first decade. Cream bottles found in the excavated trash dump were used to transport the cream from the dairy to the Refectory, or perhaps also to other places in Amherst County. In the later years of the dairy, it was able to produce enough milk to satisfy the demands of the students and to sell in the Lynchburg area. Even though the dairy is gone, it and cows will remain part of Sweet Briar’s image for many years to come. There are many pieces of the College that have come to symbolize a Sweet Briar utopia. This ideal image of the College is constructed from its distinguishing characteristics, the programs that separate Sweet Briar from the hundreds of other colleges and universities in the country. These images of Sweet Briar can be traced to the first decades of the College and are visible in the archaeological record. Conclusion Today, Sweet Briar College stands as a testament to the value of Indiana Fletcher Williams’ vision of educating young women and the success of the board of directors in making it a reality. Nearly every aspect of the early College confirmed its mission to create a place for young women to learn. Sweet Briar’s country location fostered a sense of isolation that allowed all members of the community to put their effort into the task at hand: for students, learning, and for faculty, teaching. The farm and dairy allowed the community to be self-sufficient to a degree. Although this isolation and self-sufficiency made Sweet Briar a separate and protected community, Sweet Briar did retain ties with the larger national and international community. Four years of focused study at Sweet Briar were intended to prepare students to contribute to a broader community after graduation. The early College, however, was not interested solely in the intellectual well-being of its students. Sweet Briar’s location also contributed to the physical health of the community. Fresh, country air and daily exercise were encouraged as appropriate measures to ensure good health. Indiana Fletcher Williams’ vision and the steps taken by the board of directors to implement it, illustrate ideals in learning that are still valued today. There are elements of Sweet Briar today that are cherished as links to the past. The riding program and student traditions are parts of Sweet Briar that continue to define the community today. In many ways, Sweet Briar remains a utopia. While higher education for women is no longer a radical idea, single-sex institutions are not common. Sweet Briar remains a unique opportunity for young women, not because there are few other choices for higher education, but because Sweet Briar remains dedicated to preparing young women to become productive members of a world community through hands-on learning. The architecture, pastoral atmosphere, and student traditions are the visual elements of the Sweet Briar utopia. The essence of the Sweet Briar utopia, however, lies in the process of education. The community of learning that was formed by the first board of directors sought to construct an isolated, residential college dedicated to serious learning. For students entering Sweet Briar in the 1910s and 1920s, this community represented an ideal where they could strengthen their minds by reading the Greek and Roman classics, conducting chemistry experiments, learning a modern language, or participating in the arts. They found equal pleasure and education outside of the classroom, on the athletic fields, along hiking trails, and in dormitory rooms. Traditional sources of information have emphasized this mythic utopian image of the College’s early years, an image in part borne out by the objects recovered archaeologically. The objects, however, also record the day-to-day life of students at Sweet Briar. These objects of daily reality are the new information that this exhibition brings to light and they have in fact changed our understanding of the College’s early years. For this reason, the objects displayed in this exhibit - Coke bottles, compacts, and light bulbs, our forebears’ trash - are truly treasures, bringing us new and different knowledge about our collective past. Bibliography Ingber, Alix ed. Traditions and Change: A Sweet Briar Anthology. Sweet Briar College, Summer 1998. Orser, Charles & Brian Fagan. Historical Archaeology. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers, 1995. Renfrew, Colin & Paul Bahn. Thames and Hudson, 1996. Schlereth, Thomas. Artifacts and the American Past. Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1981. Schlereth, Thomas, ed. Material Culture Studies in America. Association for State and Local History, 1982. Stohlman, Martha. The Story of Sweet Briar College. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956. Toulouse, Julian Harrison. Bottle Makers and Their Marks. Camden, New Jersey: Thomas Nelson, Inc, 1971. The Tenth Year Book of Sweet Briar College 1915-1916. Catalogue of Sweet Briar College 1925-1926. http://www.oral-care.com/listerine.html, 11/19/98. Archaeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice. Nashville: London: American