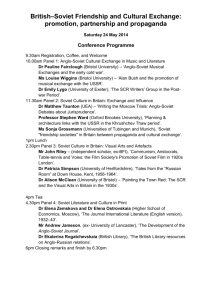

Allies and Adversaries:

advertisement

Allies and Adversaries: The Joint Chiefs of Staff, The Grand Alliance, and U.S Strategy in World War II Mark A. Stoler, Allies and Adversaries: The Joint Chiefs of Staff, The Grand Alliance, and U.S. Strategy in World War II. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000. xxii 1 380 pp. $37.50. When did U.S. foreign policy begin to adopt a global strategy that increased the role of military planners? Many scholars have emphasized the rise of the National Military Establishment and its pivotal role in the shaping of a "national security policy" during the early Cold War. Mark Stoler shifts the emphasis, showing how the "full-scale U.S. participation after Pearl Harbor in a global and total war" (p. x) allowed the armed forces for the first time to assume a crucial role in policy formulation. Offering new archival evidence and extremely detailed analysis, this study sheds valuable light on U.S. military strategy as well as interallied diplomacy. [End Page 129] Traditionally, U.S. military planners had deferred to civilian authority. But under the imperatives of imminent global war, Stoler reminds us, that tradition was reversed: the first State-War-Navy Liaison Committee was established in 1938; coordinated planning continued to evolve with the Joint Army-Navy Board's shift to the Executive Office of the President a year later; this led to the establishment of the much more powerful Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor; and it was after the JCS had repeatedly demonstrated its excellent record in war and postwar planning that the State Department accepted the creation of a State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee in 1944. Besides highlighting the role of JCS representatives Ernst King and George Marshall, Stoler credits military planners such as army General Stanley Dunbar Embick and Admiral William D. Leahy (the first chief of staff to the commander in chief), for their determination to expand the role of the uniformed heads in policy making. Stoler traces the origins of the wartime strategic debates to the interwar disputes between army and navy leaders. Scarred by the First World War experience, and always wary of British intentions, army planners advocated hemispheric defense and, well into 1941, only indirect material support of Great Britain. The navy, by contrast, sought to promote cooperation with Britain and to achieve supremacy in the Pacific by stressing a global view of U.S. national policies. Once the United States became involved in the war, these conflicting views found two common denominators: a global strategy that emphasized the importance of facilitating as well as keeping in check Soviet efforts to repel the Nazi armies and a growing disenchantment with Britain's manipulative reliance on a Mediterranean strategy. By focusing on Anglo-American differences, Stoler is able to pinpoint the origins of U.S. global planning. Even before Pearl Harbor the armed forces realized that "countering British proposals would require a global rather than a hemispheric alternative, one which would clearly delineate U.S. national interests"; and since both the president and the State Department had failed to "prioritize an appropriate course of action," the military planners began to assume the initiative (p. 29). Britain's tendency to outmaneuver the Americans in the interallied conferences of 1942-1943 confirmed the need for a general strategy, leading the JCS to emulate London's coordination of war aims with broader national goals, including planning for the postwar order. Particularly stunning in this account is the revelation that the U.S. armed forces soon abandoned their support for a Germany-first strategy in favor of a Pacific-first approach. This change was in part a reaction to Britain's emphasis on Mediterranean operations, which both army and navy leaders saw as conductive primarily to British imperial interests. Also, as Marshall and King argued, their Pacific-first proposal "would do more to help the Russians than any Mediterranean activity" (p. 265), preventing a Japanese attack on the Soviet Far East. President Franklin Roosevelt was never converted to a Pacific-first approach, but from mid-1943 he concurred with his JCS advisers that Churchill's politically motivated strategies had become a hindrance and that cooperation with the Soviet Union was necessary to win both in Europe and against Japan. [End Page 130] These considerations prompted the United States to accommodate the Soviet Union for the time being, a posture that seemed justifiable inasmuch as the projected opening of the second front in Europe was likely to prevent the Soviet Union from dominating the peace table. The JCS and its own advisory branch, the Joint Strategic Survey Committee, also emphasized—and certainly overestimated—the importance of a Soviet contribution to the Pacific War after Germany's defeat. The military planners were more astute in their insistence on expanding U.S. bases, particularly in the Mandated Islands, for the postwar period. This idea, however, presupposed a spheres-ofinterest approach that neither Roosevelt nor the State Department was ready to accept as an alternative to a postwar international organization. Not until the presidency of Harry Truman did the JCS gain approval for the basing policy. The growing focus on Soviet power was founded on the realization, spelled out by U.S. military planners at the end of 1944, that the postwar period would be "the age of the Big Two" (p. 227) and that Britain was on the decline. This realization compelled the United States to seek to adjust its differences with the Soviet Union for the war effort and even make concessions in Eastern Europe while foiling Britain's designs there. Eventually, younger U.S. officials, joined by Navy Secretary James Forrestal, insisted that the United States should prevent further Soviet expansion by relying on its naval and nuclear power more than on British support. After the Soviet Union repeatedly violated the Yalta agreements, and, even more, after the use of nuclear bombs against Japan made Soviet intervention there irrelevant, the U.S. armed forces reassessed the need to protect allies in Western Europe and even to preserve the European empires. This reversal was particularly significant for the U.S. Army, which abandoned its unilateral, limited strategy as well as its Anglophobic sentiments. Stoler's book certainly underscores the increasing influence of the JCS in policy making. He correctly points out that starting from the interallied conferences of late 1943 the Joint Chiefs got most of what they wanted. He also reveals that military planners formulated several wartime and postwar policies, such as unconditional surrender or a proposed international police force, before the president enunciated them. But Stoler's conclusion that military planners "dominated policymaking during the war" (p. 266) unduly stretches the point. His definition of the planners' relationship with the president as "symbiotic" seems more plausible. The broader question that Stoler fails to address is whether all this influence really translated into a capacity to conceive a "grand strategy." He emphasizes the military planners' frustration with the president's political expediency and with his tendency to rely on erratic, short-term military solutions. But then Stoler admits that some of the most salient proposals from the armed services, such as the Pacific-first approach, the proposal for a trusteeship system, and even the military's tendency to "appease" the Soviet Union, were rather myopic and counterproductive. Above all, as Stoler also concedes, the military planners' reversal of mid-1945 was a "paradigm shift" from traditional anti-British sentiments based on a "limited view of U.S. national security concerns" to a new strategy "based on an unlimited, global view of [End Page 131] both U.S. national security and Soviet goals" (p. 268). In that sense a JCS "grand strategy" did not fully emerge until the dawn of the Cold War. More poignant and deserving further analysis is Stoler's point about the Joint Chiefs' ability to incorporate economic and political considerations into their plans. Especially notable was the planners' effort to minimize U.S. casualties as a "political goal" for a "democratic society at war" (p. 269). Stoler's argument surely gains merit from this finding. Perhaps Stoler's book is not as provocative as he intended it to be, but it certainly provides new insights into the interplay between policy makers and military planners. For some time it will remain a standard reference on wartime strategy and diplomacy. Alessandro Brogi Yale University