SB829 assign 1

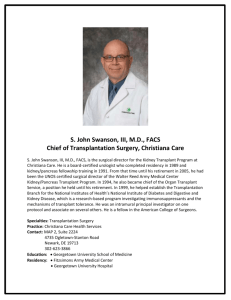

advertisement

Andrea Kelley SB 829 March 13, 2012 Assignment 1 The National Kidney Foundation reports that 26 million Americans have chronic kidney disease, a condition that often leads to kidney failure or end stage renal disease (ESRD).1 Malek, Keys, Kumar, Milford, and Tullius reported that by the end of 2010, 700,000 people in the United States were predicted to advance to ESRD from chronic kidney disease.2 The overall Medicare cost for managing ESRD was $17 billion in 2002.3 For patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD), continued well-being depends on critical treatments: either dialysis or kidney transplantation. Due to the shortage of organs, most patients will progress to dialysis before transplantation. While dialysis does lead to patients feeling improvement, it has some negative aspects as well. While receiving dialysis, a patient is either committing to a time-consuming home treatment (peritoneal dialysis) or an average of nine hours per week at a dialysis center for hemodialysis. Access to kidney transplantation offers possible improvement of patients' health and lifestyle. Transplantation has been shown to increase a patient's longevity, lead to lower cost of healthcare, and improvement to quality of life.4 Considering the patient population in the United States, there is a disproportionate number of black Americans with ESRD. In the year 2000, blacks represented 12.7% of the U.S. population and 32% of the ESRD patient population.5 African Americans had a four-fold increase in the incidence of ESRD when compared to the Caucasian population.6 Of those patients pursuing a transplant, 33% are African American and over 50% are ethnic minorities. While waiting for their transplants, the mortality rate is twice that for nonwhite patients as it is for white patients and white patients overall receive their transplants sooner.7 In a study reviewing transplant rates for patients in Wisconsin, the authors found that African American patients diagnosed with ESRD between 1982 and 1985 were 35% less likely to receive a kidney transplant than their white counterparts. This rate worsened with time – patients diagnosed between 2001 and 2005 who were African American were 74% less likely to be transplanted.8 Several studies found that non-white and African American patients had a transplant rate approximately half of that of whites.9 One study in the Southeast found the 1 “Kidney Disease,” National Kidney Foundation, accessed March 11, 2012, http://www.kidney.org/kidneyDisease/. 2 Sayeed K. Malek et al., “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Kidney Transplantation,” Transplant International 24 (2010): 420, Accessed March 1, 2012, doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2010.01205.x 3 R. S. D. Higgins and J. A. Fishman, “Disparities in Solid Organ Transplantation for Ethnic Minorities: Facts and Solutions,” American Journal of Transplantation 6 (2006): 2556. 4 G. Caleb Alexander and Ashwini R. Seghal, “Why Hemodialysis Patients Fail to Complete the Transplantation Process,” American Journal of Kidney Disease 37 (2001): 321. 5 Joanne M. Churak, “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Renal Transplantation,” Journal of the National Medical Association, 97 (2005): 153. 6 Higgins and Fishman, “Solid Organ Transplantation,” 2556. 7 Malek, “Disparities in Kidney,” 419. 8 Kelly L. Stolzmann et al., “Trends in Kidney Transplantation Rates and Disparities,” Journal of the National Medical Association, 99 (2007): 927-928. 9 Eszter Panna Vamos, Marta Novak and Istvan Mucsi, “Non-Medical Factors Influencing Access to Renal Transplantation,” International Urology Nephrology, 41 (2009): 608, Accessed March 11, 2012, DOI transplant rate to be 59% less for African Americans and that there were disparities throughout the steps of the transplant process.10 Of transplanted African Americans, the average national time of the waiting list was 1,335 days compared to 734 days on average for Caucasian patients.11 Having a shorter waiting time is important because earlier transplants have been shown to be related to a better prognosis overall.12 Another significant and sometimes overlapping demographic that impedes access to a renal transplant is low socioeconomic status. In the study of the Southeastern transplant center mentioned previously, the authors sought to examine whether poverty accounted for the racial disparities in transplantation. While income level did not account for all disparities, it was considered to be explanatory in about one third of African Americans surveyed.13 A number of other studies have indicated that socioeconomic status acts as a potential barrier to transplantation.14 One study suggested that patients with high income were five times as likely to receive a transplant as those in the low income bracket.15 Therefore, the ideal target audience for the intervention is African American adults with low socioeconomic status diagnosed with ESRD. Examining the causes of the disparity reveals a multifaceted and complex issue. There are a number of biological and genetic factors that are cited as contributing to the decreased transplants among the African American population. Transplant protocol requires matching by ABO blood type and human leukocyte antigen (HLA). In patients with ESRD waiting for renal transplant, most African Americans have blood group B or O which has a wait time twice that of patients with group A and four times that of AB.16 Additionally, African American patients have been shown to have increased immunological response and require more closely matched HLA typing.17 Illnesses that lead to ESRD and can complicate renal transplantation are also higher in the African American community, including diabetes and hypertension.18 Due to the lower rates of organ donation by the black population, it can be harder to find a good match.19 In addition to the genetic factors of the patients and donor pool, there are causes to be found within the medical community. One report suggests that internalized racism may be a factor in the decreased numbers of black patients being referred to the transplant evaluation. The youngest black candidates were 40% less likely to be listed than similar white patients and the healthiest black candidates were 50% less likely.20 In a study of physician opinions, nephrologists were less likely to believe that kidney transplant equaled better survival rates for 10.1007/s11255-009-9553-x 10 R.E. Patzer et al., “The Role of Race and Poverty on Steps to Kidney Transplantation in the Southeastern United States,” American Journal of Transplantation, 12 (2012): 358. Accessed on March 10, 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.16006143.2011.03927.x 11 Clarence E. Foster III et al., “A Decade of Experience With Renal Transplantation in African-Americans,” Annals of Surgery, 236 (2002): 794. 12 Stolzmann at el., “Trends in Kidney,” 923. 13 Patzer et al., “The Role of Race,” 358. 14 Sankar D. Navaneethana and Sonal Singh, “A systematic review of barriers in access to renal transplantation among African Americans in the United States,” Clinical Transplantation, 20 (2006): 772, Accessed on March 3, 2012 DOI: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00568.x 15 Churak, “Disparities in Renal,” 153. 16 Vamos, Novak and Mucsi, “Non-Medical Factors,” 612. 17 Malek, “Disparities in Kidney,” 421. 18 Malek, “Disparities in Kidney,” 419. 19 Churak, “Disparities in Renal,” 156. 20 Churak, “Disparities in Renal,” 152. black patients than for white patients. They also believed there was less improvement in quality of life for African American patients than Caucasian, although that difference was smaller. 21 Physicians' beliefs about the benefits of transplantation for a certain population can affect their referral rates for that group. Other environmental causes include inadequate health insurance, lack of donors both live and cadaveric, and lack of education at dialysis centers. In some studies, authors use lack of health insurance as a stand-in for low socioeconomic status. Since insurance coverage is often a requirement for activation on the transplant waiting list, patients' access may be impeded by lack of or inadequate health insurance. As discussed previously, there is a smaller percentage of black organ donors both living and cadaveric. Some sources attribute this difference to religious ideals in the black community.22 Finally, one study found that patients who were listed as “uninformed” about the transplant benefit on Medicare forms had a 53% lower rate of access to transplantation.23 In this study, African Americans were 27% more likely to judge psychologically unfit for transplant, and therefore not informed of the benefit. Another study found white and black patients to be equal in number informed of transplantation, but the informed only totaled half of patients.24 In the ecological model, both environmental and individual factors should be considered. In addition to biologic and genetic factors that were listed previously, a number of individual behaviors are connected to the disparate rates of renal transplantation. One aspect is the black patient's interest in receiving a transplant. Churak suggests that patients' focus on managing current problems and multiple stressors, combined with a lack of knowledge about the benefits, may lead patients to not prioritize following through with the transplant process.25 Considering the lower rate of live donors for African American patients, it has been posited that their perception may influence the likelihood of asking or persuading people to be donors.26 Black patients have been reported to have better energy levels and satisfaction with dialysis overall, which may also contribute to them not completing the transplant evaluation.27 Failure to complete the transplant evaluation is one of the major reasons attributed to lower rates of listing for black patients. In comparing the pathway through the transplant evaluation for black and white patients, one study found that blacks were more likely to get stuck at all the steps in the process.28 Some factors that may contribute to patients failing to progress through the evaluation or get listed include actual or perceived substance abuse, housing instability, lack of medical compliance, and mistrust of the medical system.29 Several studies indicate the increased education and health literacy lead to increased 21 Ayanian et al., “Physicians’ Beliefs About Racial Differences in Referral for Renal Transplantation,” American Jounral of Kidney Diseases, 43 (2004): 353. 22 Vamos, Novak and Mucsi, “Non-Medical Factors,” 611. 23 L. M. Kucirka et al., “Disparities in Provision of Transplant Information Affect Access to Kidney Transplantation,” American Jounral of Transplantation 12 (2012): 351, Accessed on March 2, 2012, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03865.x 24 N. G. Kutner et al., “Perspectives on the New Kidney Disease Education Benefit: Early Awareness, Race and Kidney Transplant Access in a USRDS Study,” American Journal of Transplantation Jan 6, 2012, Accessed on March 2, 2012, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03898.x 25 Churak, “Disparities in Renal,” 156. 26 J. L. Gore et al., “Disparities in the Utilization of Live Donor Renal Transplantation,” American Journal of Transplantation 9 (2009): 1130, Accessed on March 2, 2012, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02620.x 27 Navaneethana and Singh, “A systematic review of barriers,” 771. 28 Alexander and Seghal, “Why Hemodialysis Patients,” 325. 29 Churak, “Disparities in Renal” access. When patients at one center were compared for education level, it was shown that there was a link between racial disparities and level of education.30 The authors suggest that mediating the effect of formal education level through targeted interventions can reduce the racial disparities in transplantation. An assessment of one center's dialysis patients found that lack of health literacy led to lower rates of referral for transplant and suggest that this is an area for potential intervention.31 A program conducted at the University of Maryland designed to improve renal transplant rates and reduce waiting time for black patients included targeted education at physician offices and dialysis centers. Their results indicated that such a program could be effective.32 Given the many factors that interact in this health disparity, it is important to consider areas that are changeable. Genetic factors in the patient cannot be easily addressed by a public health program, but rather call for scientific advances in immunosuppressant medicine. Insurance coverage is an area of constant debate in the United States currently. If the Affordable Care Act in enacted, many of the patients who are currently ineligible due to inadequate insurance coverage may become eligible. Some of the long standing issues that face African Americans, including institutional racism, poverty, housing instability, poor diet, lack of exercise, and higher prevalence of certain illnesses are areas that may be addressed in an intervention, but for the purpose of feasibility are excluded here. Similarly, programs to address lower rates of organ donation in the black community have been shown to be effective in the past but would pull focus from other objectives proposed here. It may be an area for future expansion of the intervention program. The proposed intervention will focus on improving access to transplantation for African American adults with low socioeconomic status. Targeted determinants include of lack of health literacy, knowledge about treatment options for ESRD and perception of poor relationships with providers. Due to the success of previous efforts focusing on the determinant of health literacy and knowledge of transplantation, this is a fertile area for intervention. Change objectives on the individual level include understanding treatment options, discussing the transplant process with providers, gaining confidence in discussing medical treatment, asking and informing live donors of the process. This will give black ESRD patients the ability to be more proactive in their health care overall and with transplantation in particular. While previous encounters with the medical profession may have left black patients with the sense that they are powerless, this intervention would encourage them to be good advocates for themselves. Once patients have greater awareness of the benefits of transplant, this will lead to them seeking services that they desire and approach their loved ones as potential donors. Additionally, the ability to advocate for themselves will help to mitigate any provider biases that lead providers to overlook black patients when referring for transplant evaluations. The strategies for these change objectives include one-on-one information sessions with targeted patients in dialysis centers, instruction in communication techniques with providers, individualized planning with patients, and a review of methods to discuss difficult topics with loved ones. Considering that African American patients are less likely to advance through the steps of an evaluation, use of the trans-theoretical model may address any resistance of the 30 Alexander S. Goldfarb-Rumyantzev et al., “Effect of education on racial disparities in access to kidney transplantation,” Clinical Transplantation 26 (2012): 79, Accessed on March 12, 2012, DOI: 10.1111/j.13990012.2010.01390.x 31 Vanessa Grubbs et al., “Health Literacy and Access to Kidney Transplantation,” Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 4 (2009): 195, Accessed on March 12, 2012 doi: 10.2215/CJN.03290708 32 Foster III et al., “A Decade of Experience.” patient and uncover the reasons for failing to advance. This model is helpful is considering all of the strategies mentioned, but will particularly effective when engaging in one-on-one planning sessions with low income African American patients. Another model to utilize is that of social networks. As more targeted patients understand their treatment options and reach out to loved ones as potential donors, organ donation will become more accepted by the community and spread throughout the networks of patients. The other aspect of this intervention will focus on the environmental factors involved. Targeted determinants include indifference of staff at dialysis and provider beliefs about suitability of black patients for transplant. Change objectives are for dialysis staff to provide education to targeted patients, nephrologists to assess their transplant referral process, and providers to be educated about racial disparities. This side of the intervention combines with the first to ensure patient awareness of transplant options. While increasing patient self-advocacy begins the process to end disparate treatment, without the involvement of providers patients may continue to be screened out or not referred. Providers of low income black ESRD patients can create an impenetrable barrier if not involved in the process. Strategies for the environmental causes include training staff at dialysis centers in providing patient education, material provided to nephrologists to assist them in assessing current referral processes, and training for providers to make them aware of disparities in renal transplantation. The persuasive communication model can be used for these strategies in order to convince providers of the necessity of their involvement in the transplant process. As stated earlier, renal transplant can lead to reduced health care costs, improved quality of life and longevity for patients. All of which should be the goals of medical providers. In sum, the intervention to be created will target on African American patients with ESRD and low socioeconomic status and improve access to renal transplantation. By focusing on increased health literacy and education for patients, we can ensure that patients are capable of advocating for their preferred treatments. Combined with strategies to involve providers, we can begin to erase some of the difference between patients in diverse demographic groups.