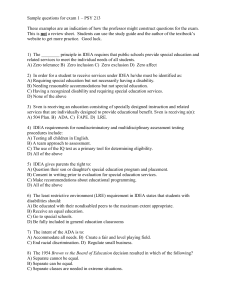

Practice Note: Why an IEP (IDEA) over a § 504 plan?

advertisement

IDEA - Individuals with Disabilities Education Act – 20 U.S.C. § 1400 et seq.; 34 C.F.R. § 300. The IDEA is the principal law relied upon by advocates to obtain appropriate education for children with disabilities. In simple terms IDEA requires public school districts to seek out and identify children with disabilities and provide them with an appropriate education in an educational environment, which is as close to the regular education environment as possible. This law requires that schools develop an annual educational plan (IEP) through an multidisciplinary team, which includes the parents. Educational advocates function primarily in the complex processes involved in the development and implementation of these educational plans. a. History – Until 1975, when the Education of all Handicapped Children Act (EHCA) or Public Law 94-14 was passed, children with disabilities had no federally protected right to an appropriate public school education. Up to that time, many severely disabled children were excluded from public school or were provided only minimal education in segregated, often dismal programs. The original EHCA was followed by successive amendments in 1983 and 1986. Then in 1990 the law was revamped and renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The IDEA has been reauthorized and amended in 1992, 1997 and most recently in November 2004. Because the IDEA and other related educational laws are continually changing and evolving, it is very important that advocates make every effort to update their knowledge of the statutes and their interpretation by the courts. To help advocates meet their ethical obligations to know the present state of the law, COPAA provides annual updates at each of its annual conferences. This year it is very important that advocates take advantage of not only the annual state of the law update (review of court cases from 2004, but also Matthew Cohen’s review of the 2004 Reauthorization. Practice Note: Why an IEP (IDEA) over a § 504 plan? Often schools are confounded when a parent or advocate insists upon an IEP under IDEA, rather than accept a § 504 Plan. Consider the important differences between a § 504 Plan and an IEP. 1. Enforceability: One practical problem with § 504 Plans is that once they are created schools tend to treat them rather casually. Often teachers are not informed of the requirements of the plan or simply fail to implement them. Most school districts have very poor provisions for enforcement or remedies for failure to implement. 2. Reviewability: An IEP must be reviewed every year, while § 504 Plans are usually created and then ignored, without reconsideration or review. 3. Provision of services: While schools may provide some basic accommodations under a § 504 Plan, they are rarely willing to provide any services or special classes. §504 is an unfunded mandate and therefore it provides no money for the provision of services. These students may need special classes (Learning strategies) and services (Functional behavior assessment, positive behavior support plan, sensory diet, socialization help, etc.). 4. Measurement of Progress: § 504 Plans do not require the establishment of present levels of performance (baseline) nor measurement of progress. Student’s with disabilities need more than accommodations. They need to be taught to compensate for and manage their disabilities. Progress toward acquiring these skills, like all education progress, needs to be measured. IEPs require present levels of performance and measurable goals and objectives. § 504 requires the provision of access to the general curriculum, but not necessarily the provision of educational benefit or progress. 5. Fewer Discipline Protections: Although students with § 504 plans do receive a few legal protections when behavioral issues arise, they are not nearly as well protected as students with IEPs. Many schools are frankly ignorant of the protections, which must be afforded 504 students and these student’s rights. Students with IEP have well developed and generally recognized legal protections. B. Legal Concepts – IDEA: It is often easiest for advocates to develop their understanding of special education law through a study of the basic legal principles, which have evolved from the statutes and the case law. Once the advocate has a grasp of these principles, it becomes easier to apply the law to the complexities of the educational process. Some of the basic principles are briefly discussed below. 1. Special Education: While most people understand that a child with an IEP (Individual Education Plan) is receiving “special education,” there is a lot of confusion about what we mean by this term. Essentially, special education is considered “specially designed instruction,” which is provided to a student with disabilities in order to assist the student successfully access education. 20 U.S.C. §1401 – Definitions (25). 34 C.F.R. § 300.26 (3) Special Education usually involves the adaptation or modification of content and/or the variation in the rate or method of delivery of instruction. Special education can also involve the teaching of skills, designed to assist the student in compensating for or overcoming this effects of the student’s particular disability. Practice Note: Special Education is a service – not a place This principle is often a matter of confusion to both parents and school staff. There is an almost automatic reflex to think of special education as involving a special class or school. This is not only inaccurate, but it violates the legal principal which holds that to the greatest extent possible, special education services should be delivered in the same class with non-disabled children. In reality a child may be eligible under IDEA, without placement in a special education class, as long as the child requires “specially designed instruction.” 34 C.F.R. § 300.26. Some examples might be a positive behavior support plan, sensory diet, social skills training or social stories, organizational aides, counseling, social work services, work planner assistance, study skills classes, etc. 2. IDEA Eligibility: Before a student can receive special education services, it is necessary that the student be found legally eligible for such services. In a global sense, IDEA eligibility requires that the student be a “child with a disability” and by reason thereof “needs” special education and related services. 20 U.S.C. § 1401 (3) Each category of disability has its own legal criteria for determining the disability and eligibility. The simple existence of a disability will not in and of itself make the child eligible for IDEA services. The law also requires that the established disability have an adverse affect on the child’s educational performance. (See Practice Note – below) Practice Note: The child must by reason of his disability require special education This is an area of growing contention between advocates and school districts. For a long time schools have denied eligibility when a child did not meet the numerical requirements for a learning disability. Now they have begun refusing eligibility even where a child might meet the necessary discrepancy between intellectual level and achievement. Schools argue that the child must “require” special education and will often deny special education services where a child receives a passing grade. This is growing problem for children with SLD, ADHD, or emotional disabilities. It is important for advocates to hold the line on this issue. It is important to argue that “education” includes more than academic performance. It also includes social, emotional and behavioral progress. A child may need special education even if the child is successful academically, where the child has social, emotional or behavioral issues. Furthermore, academic success is not only a question of advancing from grade to grade or “doing as well as the others in the class.” Failing grades are not necessary to qualify. 34 C.F.R. § 300.121 (e) Schools are regularly advancing students, who cannot read appropriately or perform essential math skills. It is important to insist that student progress be measured using nationally normed evaluations and not subjective teacher measures. Disability categories: It is important that the advocate have a good understanding of the various legally recognized disability categories. There are presently thirteen recognized categories of special education eligibility. The specific eligibility criteria of each category can be somewhat complex and are usually grounded in psychological, communicational, or physical assessments. The advocate should at least be able to locate the precise legal criteria for each disability category and should be capable of understanding the assessment procedures used to determine eligibility. A few of these primary categories are: Developmental Delay/Mental Handicaps (Mental Retardation): Some children are considered disabled due to developmental delays or mental handicaps. In the language of the regulations this disability refers to “significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning, existing concurrently with deficits in adaptive behavior and manifested during the developmental period, which adversely affects a child’s educational performance. 34 C.F.R. § 300.7 (c) (6). Due to intellectual deficiencies these students have difficulty learning and retaining skills and knowledge. Most schools classify these students’s according to their I.Q.s (the I.Q ranges may vary), labeling them as: Educable Mentally Handicapped: (60 to 69) These children are often physically and otherwise indistinguishable from their typically developing peers. At another time they might have been labeled “slow,” due to their greater need for concrete, repetitive, segmented, and sequential learning. Trainable Mentally Handicapped: (35/40 to 59) Students in the trainable range are more severely impacted by their intellectual deficits. While they can clearly learn and are capable of developing basic reading, math, writing, and other academic skills, the process is generally much more difficult for them. Learning requires great effort and time. Memory deficits often complicate the learning process. These children often have co-morbid language, speech, gross and fine motor and physical disabilities. Many children with Downs Syndrome fall within this classification. Severe or Profoundly Handicapped: (Up to 35/40) Children within the severe or profound range of disability have generally experienced severe genetic disorders and their low intellectual capacities are most often accompanied by significant physical handicaps. It is generally very difficult for these children to learn the most basic living skills. Very often these children have severe speech impairments or are non-verbal. Specific Learning Disability (SLD): Some students with normal or even superior intellectual capacities still have significant difficulties learning. These students have difficulty processing information being presented in the teaching process and they are considered to have a specific learning disability. In general terms a student’s eligibility for services under the specific learning disability is determined by psycho-educational evaluations of the student’s intellectual level and achievement. When these evaluations show at least a 1 to 1.5 standard deviation (depending upon age) between the student’s I.Q. and achievement (in at least one domain of achievement- reading, listening, speaking, thinking, writing, spelling, mathematical calculations), then the student may be considered to have a specific learning disability. A true specific learning disorder must be caused by a processing deficit, rather than some other cause such as illness, visual or hearing impairments, or language deficits. Specific learning disability is probably the category whose eligibility relies most upon objective evaluations. The criteria for eligibility are covered in detail in statute and regulations. 20 U.S.C. § 1401 (26); 34 C.F.R. § 300.7 (c) (10); 34 C.F.R. § 540 through § 543. Practice Note: Specific Learning Disability is only a label – What is the Disability? When schools evaluate children for specific learning disabilities, their assessments are often eligibility assessments. This means that the school is evaluating the child to determine if the student has a learning disability. Unfortunately school’s usual stop there. Too often the school can tell the parent that the child does have a disability, but they are unable to define clearly and precisely how the disability affects the student’s ability to learn. A learning disability is always the result of the child having difficulty processing information. This processing problem may be different from child to child. One child might have difficult processing certain visual information, while another might have problems processing certain auditory information. Another child might have difficulty processing or retaining short term or long term memory. The essential point here is that unless we understand how the disability specifically affects the student, we cannot know how to best teach the child or to help the student overcome the disability. It is vitally important that the advocate not accept incomplete assessment. The school must be able to explain the nature of the student’s disability and to identify the appropriate methodologies for supporting the student’s learning. Autism: Autism was added as a separate disability in the 1997 amendments to IDEA. Autism is legally defined as “a developmental disability significantly affecting verbal and nonverbal communication and social interaction, generally evident before age 3, that adversely affects a child’s education performance. Other characteristics often associated with autism are engagement in repetititive activities and stereotyped movements, resistance to environmental change or change in daily routines, and unusual responses to sensory experiences.” 34 C.F.R. § 300.7 (c)(1)(i); Autism is a term often used to define a wide spectrum of disorders beyond the attributes of “classic” autism. Because many students may present the various autistic traits to varying degrees, it is possible that some students fitting within the autism spectrum (PDD-NOS) may not meet the precise criteria for the educational criteria of autism. In such cases the OHI category (See below) for disability eligibility may be used to qualify the student for services. Other Health Impaired: Not all disabilities fit so easily into a category. Congress has provided a catch all category, covering a number of disabilities and problems, including but not limited to ADD/ADHD, diabetes, epilepsy, acute or chronic health problems. In specific terms, the “other health impaired” category includes health or psychological disorders which are characterized by: “Limited strength, vitality or alertness, including heightened alertness to environmental stimuli, that results in limited alertness with respect to the educational environment – that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.” 34 C.F.R. § 300.7 (c)(9)(i-ii) For years schools insisted upon attempting to serve children in the “other health impaired” category with 504 plans. Now it is clear that a child in this category may have the right to an IEP under IDEA, if the disabling disorder as a significant impact on the student’s education. Too often schools will argue that a child in the OHI category does not qualify for an IEP, where the student makes passing grades. They make this argument because they incorrectly equate “education,” with “academic” performance. Very often children in the OHI category are very intelligent and may demonstrate at least “passing” academic success. At the same time a child with an OHI disorder may have significant social, emotional or behavioral issues. Failure to make adequate progress in these areas will qualify a student for services, even if the child is passing from grade to grade. See also Practice Note: The child must by reason of his disability require special education – on page 12. Emotional Disorder: Children with recognized emotional disorders are qualified for special education services. An student with an emotion disorder should have one or more of the following conditions (34 C.F.R. § 300.7 (c)(4)): - Inability to build interpersonal relationships (peers and teachers) - Inappropriate types of behavior or feelings under normal circumstances - Pervasive mood of unhappiness/depression - Tendency to develop physical symptoms, fears, associated with school problems In addition, the conditions must be chronic in that they: - Exist over a long period, - To a marked degree, and - Adversely affects educational performance The law insists that the inappropriate behavior manifested by the student now be what the laws describes as social maladjustment or simple bad behavior alone. Sometimes schools will resist the classification of a child as emotional disordered on the grounds that the student is simply acting out or misbehaving and that there is no true emotional disorder involved. For this reason it is important to firmly establish the psychological basis of the disorder. Practice Note: Emotional Disorder does not equal Special Class Often parents hesitate to allow the identification of their child as emotional disordered, because they fear that their child will be placed in an Emotionally Disordered class. These classes are viewed as dead end classes for bad kids. In reality many children with emotional disorders can function successfully in regular classes, with appropriate accommodations and services. Practice Note: Student’s with Emotional Disorders need Protection of IEP If a student has a true emotional disorder it is essential that the child have the protections of an IEP. Very often only proactive advocacy establishing appropriate IEP accommodations, a functional behavior assessment and a positive behavior support plan can protect the student against the punitive structure of school discipline. Formal recognition of the emotional disability will assure that the student will have protection against expulsion. It is generally far easier to establish the disability before a student encounters a serious discipline problem, than to try to obtain recognition of the disability when the school wants to punish the child. Speech and Language, A “speech or language impairment means a communication disorder, such as stuttering, impaired articulation, a language impairment or a voice impairment, that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.” 34 C.F.R. § 300.7 (c)(11). 3. Free and Appropriate Public Education. 20 U.S.C. § 1401 (8); The obligation of school districts to educate children with disabilities is summarized in the requirement for schools to provide a “free and appropriate public education.” This is a power packed phrase and is the core principle governing every issue related to the education of those with disabilities. The requirement of a “free” education means that the school may not require any payment for the provision of education. If assistive technology, special books, transportation, etc. are required in order for the child to receive an appropriate education, then they need to be provided without charge. The definition of the word “appropriate” as it related to the education of those with disabilities could fill volumes. Almost every due process administrative hearing or court case will turn around whether or not the school district has offered an “appropriate” education. The IEP is the vehicle or plan for delivering this “appropriate” education and appropriateness will be decided through the subjective finding as to whether the IEP is “reasonably calculated to confer educational benefit.” 4. Least Restrictive Environment: The principle of education in the least restrictive environment harkens back to the origins of special education law. Prior to 1975 many children with disabilities were not offered any public education. Those who were provided some education were generally segregated into separate institutions, schools or classes. In this sense the § 504 and IDEA are truly anti-discrimination laws. In simple terms these laws require that children be educated in an environment as close to the regular education environment as possible. These laws raised a rebuttable presumption that disabled children should be educated with their non-disabled peers. Only when all reasonable efforts, including accommodations, modifications, and supports, have been unsuccessful in providing an appropriate education in the regular placement, may the school begin to restrict the students educational environment. In determining whether a student is capable of receiving an appropriate education in a regular education or other inclusion class it is not necessary that the student be successful in the same way as the typically developing peers. It is only necessary that the student be able to make educational progress according to the student’s own abilities and nature. It has been held that social benefit may be sufficient grounds for approving mainstream education for a child with a disability (See also IEP-Placement) ”To the maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities, including children in public or private institutions or other care facilities, are educated with children who are not disabled, and special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular educational environment occurs only when the nature or severity of the disability of a child is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactory.” 20 U.S.C. § 1412 A (5); 34 C.F.R. § 300.130; 34 C.F.R. 300.550 through 556. 5. Stay Put: Congress recognized that at some point in a child’s education a dispute might arise between the student’s parents and the school district as to the appropriate educational plan for the child. In an effort to maintain a certain equilibrium between the parties during the resolution of the dispute, the law has established the principle of “stay put.” This means in simple terms that the student shall remain in the current educational placement “during the pendency” of due process administrative hearing or Court trial. The child can be moved to another placement during the pendency of the resolution only by mutual agreement of the parties. “… during the pendency of any proceedings conducted pursuant to this section, unless the State or local educational agency and the parents otherwise agree, the child shall remain in the then-current educational placement of such child, …” 20 U.S.C. § 1415 (j)