HS MLA Handbook - Sutton School District

advertisement

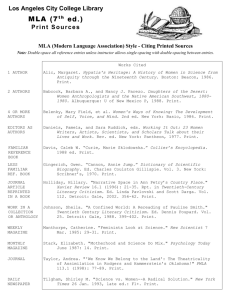

Sutton Memorial High School Guide for Writing and Reference Developed by the members of the Sutton Memorial High School English Department Christina C. Corsa Kari S. Farmer Kylie A. Lauder Cameron Loss Sergio Marcucci Table of Contents Academic Integrity o Plagiarism o Consequences of Plagiarism 3 3 3 Finding a Focus o Choosing a Subject o Subject vs. Topic o Generating an Opinion & Creating a Thesis Statement 4 4 5 6 Conducting Research o Favorite Resources from the English Department 7 7 Evaluating Sources 8 Using Quotations, Notefacts and Note Cards 9 Outlining Your Essay 11 Using Textual Evidence and Parenthetical Documentation 12 How to Incorporate Textual Evidence Correctly o Using the Conjunction That o Using an Incomplete Sentence Anchor o Using a Complete Sentence Anchor o Weaving Textual Evidence into an Argument o Block or Long Quotations o Additional Examples Poetic Works Multiple Sources by the Same Author 13 14 14 15 15 16 Formatting Your Paper 19 Preparing the Works Cited Page o Types of Works Cited Entries Book and Nonperiodical Publications Articles and Other Publications in Periodicals Miscellaneous Print and Nonprint Resources Electronic Publications 22 Building a Works Cited Page Sample Works Cited Page 29 31 Appendixes o Sample Research Paper o Presearch Worksheet o Developing the Research Topic Worksheet o Outlines for Essay Writing 32 32 36 37 39 2 17 18 22 24 25 28 Academic Integrity Plagiarism As a researcher, you have a responsibility to work with integrity. This means you work within a personal code of honesty to do the most accurate research possible and give credit when you refer to the work or ideas of others. Unethical communicators deliberately fabricate information or commit plagiarism, two kinds of behavior you, as a researcher, must avoid. Also be aware that accidental plagiarism is still plagiarism; a lack of knowledge in regards to proper credit, citation, and documentation is not an excuse. Use this guide and what you already know about proper research and documentation to properly and adequately credit the resources you use throughout the writing process. Fabrication involves inventing or making up information as part of the research process. Although you might be tired or frustrated in your search for appropriate information, as an honest researcher you cannot create an interview, quotation, or article title. This point should be obvious. Plagiarism involves representing the words or ideas of others as your own. The most obvious example is handing in or performing work written by someone else and claiming it as your own. Consequences of Dishonest Behavior and Plagiarism The academic integrity of our students is a paramount concern. It is expected that students will exercise the highest standard of academic integrity and understand that any act of academic dishonest will not be tolerated. Some examples of academically dishonest behaviors include: Cheating on tests, quizzes, or exams Plagiarism from any source (Plagiarism is copying someone else’s work or including someone else’s ideas and claiming it as your own work) Fabrication of events or facts, and submitting it as factual Copying of homework, class work, or any other work from another student Submitting previously submitted work without substantial change or improvement; submitting a previously submitted paper of another student, sibling, or friend Academic dishonesty also involves aiding or encouraging others to copy, plagiarize, borrow, or steal the ideas or works of another, with the intent to offer such work as their own. It also involves allowing someone to use your work as his or her own. In accordance with the student handbook, any student found guilty of cheating or plagiarism will automatically receive a zero for the assignment and will be referred to the administration for disciplinary action. Repeated offenses may jeopardize academic credit being issued. Any violations of academic integrity involving students will also be reported to the National Honor Society advisor. Membership in the National Honor Society may be denied for any student who is found guilty of academic dishonesty. 3 Finding a Focus How do I go about choosing a subject? Often teachers will assign a topic to research; however, many times students are given the freedom to choose a subject. Here are several methods that might help in selecting a topic. Brainstorm Think of a subject that already interests you. It might be related to somewhere you have been, a hobby, a documentary you have seen on TV, or even a culture you might find interesting. Ask Questions Ask friends or family what they find interesting or unusual. Perhaps you know someone with an intriguing occupation, unusual history, or a rare hobby. Scan Books and Videos Go to the library and browse the books, magazines, and indexes for subjects that might interest you. Research Your Own Family Perhaps there is someone in your family who did something unusual or lived in an exotic place. A paper on this topic should not just be an interview of this person, but would include research on the topic. Consider a Literary Subject Consider different literary genres. Is there one that interests you? Are you curious about a particular author, poet, or playwright? Browse Through the Encyclopedia If you find a subject here that interests you, try to locate other information on that subject. While an encyclopedia can be a valuable resource, it CANNOT be the only resource. Check Out the Internet There are many lists for research topic ideas on the Internet. To help organize your ideas, use the Presearch worksheet available in Appendix B. 4 Finding A Focus What is the difference between a subject and a topic? After choosing a subject, writers must then find a topic to explore within that subject. A subject is broad and general. Some subjects might be Television, Ecology, or Science Fiction. A topic is the specific issue that will be discussed. For example, a possible topic on the subject of television is the effects of viewing television violence on children’s behavior. One of the best ways to narrow your subject into a workable topic is to use basic research questions. These can be developed through brainstorming or by using the lead questions that are used in journalism: the five W’s and the H. WHO, WHAT, WHEN, WHERE, WHY, and HOW What do I already know about this subject? What does it involve? What are the causes and/or effects related to this subject? Who is involved? Why are these people involved? Where does it take place? Where did it originate? Is the location or origin important to the topic? How? When did it happen? When was it discovered? When will it happen again? Why is this information important? Why is this information helpful? How did it happen? How did it begin? How does it affect society? To help develop your research topic more thoroughly, use the Developing the Research Topic worksheets available in Appendix C. 5 Finding A Focus How do I turn an opinion into a thesis statement? After creating a list of questions that relate to the topic, find a main question that concerns you. After careful study and research, determine your answer to this question. The answer to this question is a statement of opinion or thesis statement. Subject Topic Within Subject Main Question Thesis Statement Example: Subject: Television Topic: Violence in Television Question: What are the effects of violence on children? Thesis Statement: Young children who are allowed to watch television programs with violent content are negatively impacted throughout their adolescence by this experience. What makes a good thesis statement? In Keys For Writers, Ann Raimes states that a good thesis statement: 1. Narrows your topic to a single main idea that you want to communicate 2. Asserts your position clearly and firmly 3. Expresses your opinion or attitude toward your topic 4. States not simply a fact but an opinion 5. Makes a generalization that can be supported by details, facts, and examples within the assigned limitations of time and space 6. Stimulates curiosity and interest in readers and prompts them to think, ‘Why do you say that?’ and read on. (Raimes 18) 6 Conducting Research Favorite Resources from the English Department This list includes a variety of resources for both research and writing/formatting papers. These sources are frequently referenced by the members of the Sutton High School English Department and can be useful in other class settings as well. Infotrac This site provides articles from scholarly periodicals. Access this website by clicking on the Infotrac icon in your Novell window or by using your public library card at http://www.cmrls.org Internet Public Library: Literary Criticism This site provides articles from scholarly periodicals analyzing authors and their works. Access this site at http://www.ipl.org/div/litcrit Modern Language Association This site offers answers to frequently asked questions concerning MLA format. Access this site at http://www.mla.org Landmark Project This site is helpful when creating entries for the Works Cited page. Access this site at http://landmark-project.com Go to “Citation Machine” on the right side of the screen. Click on the type of source at the left. Type in all information that applies. The entry with correct punctuation will appear. Both MLA and APA documentation is provided. OWL: Online Writing Lab at Purdue University This site contains online exercises and links to other resources for writing assistance. This is one of the best academic sites for writing help. Access this site at http://owl.english.purdue.edu/ For information specifically related to MLA documentation, see http://owl.english.purdue.edu/handouts/research/r_mla.html A Guide for Writing Research Papers Based on Modern Language Association (MLA) Documentation This site, prepared by the Humanities Department at Capital Community College, provides suggestions on research techniques and patterns of documentation based on the style recommended by the Modern Language Association. Access this site at http://www.ccc.commnet.edu/mla/index.shtml Research and Documentation Online This site offers a variety of information. It includes format guidelines, sample essays, in-text citations guidelines and Work Cited/Consulted guidelines. Access this site at http://www.dianahacker.com/resdoc/ 7 Evaluating Sources When conducting research, it is not enough to merely amass a multitude of sources; you must also evaluate the quality and the credibility of the sources you plan to use. Printing or posting information does not guarantee credibility. Just think about how easy it is to create a website in this day and age. When choosing a source to cite or consult during the writing process, make sure the source conforms to the following criteria. The criteria for this checklist has been obtained from the Sharon Public Schools Research and Writing Guide. 1. Credibility a. Is it a trustworthy source? b. Does it give the author’s credentials? Is the author qualified to write this document? c. Is the document published in a credible venue (in a scholarly journal or website or through a reputable organization)? 2. Accuracy a. Is the source up to date? b. Is it factual? c. Is it detailed? d. Is it comprehensive? e. Does the source present the information with logic and without bias? 3. Fairness a. Is it balanced? b. Is it objective? c. Does it engage the subject thoughtfully and reasonably? d. Is it concerned with the truth? 4. Support a. Is there a works cited/bibliography at the end of the source? b. Can the information be verified? c. Are the basic facts the same in more than one source? d. Has the work been read and recommended for publication by experts? More information about evaluating sources can be found in Chapter 1 of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers. 8 Using Note Cards Information for this section is taken from the IIM Independent Investigation Method Teacher Manual. For more information on this subject, please consult the “Proficient Level: IIM Student Workpages” section in this manual. Why should I use note cards for my research and information when I’m writing a paper? Note cards can be used to organize your ideas and the research you have completed on a topic. This method is similar to outlining, as it enables the writer to break the various components of the essay into individual sections. This way, the writer can arrange and re-arrange the order the information will be used in when writing the paper. Think of it like a puzzle. Once you have formulated your thesis, completed your research, theorized the major points you will address in your essay, and noted the quotations and ideas you want to include as evidence, all of the information will be organized onto individual note cards. Then you simply move the cards around until you have established an order and a flow for your essay that will most effectively argue and prove your thesis. What information do I include on the note cards? You will use two types of note cards 1. Source Cards 2. Quotation or Notefact Cards Using A Source Card On a Source Card, you list the individual source from your research in MLA format. That way you always have the citation information handy. Example of a Source Card: 1 Source is listed in MLA format. Stoker, Bram. Dracula. New York: Bantam Books, 1981. 9 Each Source Card is numbered sequentially. This number will correspond with the information included on the Notefact or Quotation Card. Using a Quotation or Notefact Card On a Quotation or Notefact Card, you would give the specific quotation or summarize the major point you want to include in your essay, along with the proper citation or documentation information. When creating Quotation Cards, keep in mind the following points. 1. Use quotation marks for direct quotes. 2. Put the proper citation information on the card so you will know how to cite the quotation when typing your paper. Example of a Quotation Card: 1-A Quotation is listed exactly as it appears in the text. “There lay the Count, but looking as if his youth had been half renewed, for the white hair and moustache were changed to iron-grey; the cheeks were fuller, and the white skin seemed ruby red underneath…” (Stoker 54). Card is numbered to correspond with its Source Card and include a letter to indicate which piece of evidence or information this is from the source. When creating Notefact Cards, keep in mind the following points. 1. Paraphrase the information or main points in your own words. Be careful not to plagiarize! 2. Keep Notefacts short, but complete enough to make sense. 3. Note the page number the information is connected with so you can locate the section easily if you want to reread the section or add additional information. Example of a Notefact Card: Summarize what you want to discuss in your essay about this point. 1-B Discuss how the Count seems to get younger as a result of his daily vampire rituals and that by sacrificing others (red blood, red=sacrifice symbolically) to his needs, he experiences new life. (Taken from page 54 of Dracula) 10 Card is numbered to correspond with its Source Card and include a letter to indicate which piece of evidence or information this is from the source. Outlining Your Essay “Writing a paper without an outline is the equivalent to going on a road trip without a map.” ~ Cameron Loss Why should I outline my essay? Why can’t I just start typing? Creating an outline will help you to organize your thoughts on your topic in a structured fashion. This process will help you to incorporate and transition through all the points you want to cover in your essay. By planning each step in your essay, you will avoid including non-essential information in your paper, choppy transitions that will undermine your overall argument, and the risk of missing or leaving out key points and arguments. Additionally, by outlining your essay, you will be able to ensure that each and every element of your paper is thoroughly and clearly supported, rationalized, and executed. What information do I include in an outline? Begin at the beginning! Your outline should start with the mention of the basic information for the topic you are covering. For example, if you are writing about a piece of literature, you would include the name of the literary work, the name of the author, and possibly some basic facts about the work’s plot that you may end up incorporating into your introduction. Your outline should always include a rough draft of your thesis statement! Your thesis statement is the central argument your essay. As such, you should always be able to refer back to it on your outline to confirm that each and every point you plan to include in the paper helps prove the argument your thesis presents. Additionally, in your outline you should indicate each major claim you will make in regards to your thesis and a brief overview of what you will need to do to support these claims. This may be in the form of a short statement that addresses what you will talk about in regards to this specific point or an exact quotation that you plan to incorporate into your essay as evidence. Once you have covered and indicated the support you plan to use to prove your thesis, you should think about what you plan to discuss in the conclusion of your essay and note these points on your outline. That way you will not forget a great idea for your conclusion as you are writing! What format should I use for an outline? Turn to Appendixes D, E and F to see sample outline formats. 11 Using Textual Evidence and Parenthetical Documentation What is textual evidence? Quotations are used to support your own ideas on a topic. Quotations should be used when a passage is worthy of further analysis to help justify the claims of a writer. Noteworthy points about textual evidence… Quotations should not take the place of your ideas. Quotations should not be used to tell the story. Why should I use textual evidence? Textual evidence or quotations are used to strengthen the argument your writing presents. Essentially, the material that you quote in an essay serves to support your claims, ideas, and arguments on a topic, making your case more effective and convincing for the reader. By using textual evidence or quotations proficiently in your writing, you are solidifying the claims you are making. By incorporating textual evidence or quotations in your writing, you are adding a second line of defense to the claims made by your thesis statement. It is a bit like having someone second your opinion in a discussion; your textual evidence proves other people support your ideas. What should be cited? All important statements of fact and all opinions, whether directly quoted or paraphrased, and all paraphrases of those facts which are not common knowledge should be documented. In most cases, the documentation should state the author’s name and the exact page in the source where you found your information. 12 How to Incorporate Textual Evidence Correctly There are five ways to properly incorporate textual evidence into your writing. 1. Using the conjunction that 2. Using an Incomplete Sentence Anchor 3. Using a Complete Sentence Anchor 4. Weaving quotations into your own prose 5. Block or Long quotations 13 1. Using the Conjunction that If you are blending the quotation into your own sentence using the conjunction that, do not use any punctuation at all. Example: Furthermore, the narrator claims that “Leiningen had met and defeated drought, flood, plague, and all other ‘acts of God’ which had come against him” (Stephenson 13). There is no punctuation separating the writer’s words from the textual evidence, only the word that. The textual evidence appears enclosed in quotation marks. The quotation is cited using the author’s last name and the page number, as the cited material is a print source. If the cited material had come from an electronic source, the last name of the author would be sufficient. All of the citation information is enclosed in parentheses. Following the parentheses is a period to denote that the entire sentence has been completed. 2. Using an Incomplete Sentence Anchor When you use an Incomplete Sentence Anchor, textual evidence is connected to an incomplete sentence or introductory phrase. Example: When Harker finds the Count lying within the box of dirt, he describes to the reader, “There lay the Count, but looking as if his youth had been half renewed, for the white hair and moustache were changed to iron-grey; the cheeks were fuller, and the white skin seemed ruby red underneath…” (Stoker 54). The writer’s words are separated from the quotation by a comma. The textual evidence appears enclosed in quotation marks. Only part of the quotation has been used as textual evidence. As a result, the quotation is ended with three periods in a row (…). This indicates that the writer has only used part of the quotation. (If using an entire quotation, remember to always the punctuation if it is an exclamation point or a question mark.) The quotation is cited using the author’s last name and the page number, as the cited material is from a print source. If the cited material had come from an electronic source, the last name of the author would be sufficient. All of the citation information is enclosed in parentheses. Following the parentheses is a period to denote that the entire sentence has been completed. 14 3. Using a Complete Sentence Anchor When you use a Complete Sentence Anchor, textual evidence is connected to a complete sentence. Example: Harker discovers the Count lying inside a large wooden box filled with dirt and describes his appearance in great detail: “There lay the Count, but looking as if his youth had been half renewed, for the white hair and moustache were changed to iron-grey; the cheeks were fuller, and the white skin seemed ruby red underneath…” (Stoker 54). The writer’s words are separated from the quotation by a colon. The textual evidence appears enclosed in quotation marks. Only part of the quotation has been used as textual evidence. As a result, the quotation is ended with three periods in a row (…). This indicates that the writer has only used part of the quotation. (If using an entire quotation, remember to always the punctuation if it is an exclamation point or a question mark.) The quotation is cited using the author’s last name and the page number, as the cited material is from a print source. If the cited material had come from an electronic source, the last name of the author would be sufficient. All of the citation information is enclosed in parentheses. Following the parentheses is a period to denote that the entire sentence has been completed. 4. Weaving quotations into your own prose Weaving the phrases of others into your own prose allows you to maintain control over your source material and can help you to produce a tighter argument. Example: Kevin is described as having “a bad temper, a savage energy” (Woiwode 85) and being “unpredictable” (Author 85). He also “couldn’t stand to lose” (Woiwode 85) and was impatient. The examples of textual evidence are effectively woven into the writer’s words. The various examples of textual evidence appear enclosed in quotation marks. The quotation is cited using the author’s last name and the page number every time a quotation is completed, i.e. every time the writer closes the quotation marks. It is essential to cite the quoted material once the closing quotations marks are used. If the cited material had come from an electronic source, the last name of the author would be sufficient. All of the citation information is enclosed in parentheses. Following the completion of an entire sentence and idea, a period is used to denote that an entire sentence has been completed. 15 5. Long or Block Quotations Long or Block Quotations are used if the section you are quoting encompasses more than four (4) typed lines in the paper. If you are using a Long or Block Quotation, you should almost always introduce it with a Complete Sentence Anchor that helps capture how it fits into your argument. Example: Grace’s descriptions of her new living arrangements are enough to make modern day sensibilities cringe, but for Grace it is the closest she has ever come to luxury: Our room was not large, and hot in the summer and cold in the winter, as it was next to the roof and without a fireplace or stove; and in it was a small bedstead, which had a pallet mattress filled with straw, and a small chest, and a plain washstand with a chipped basin, and a chamber pot; and also a straight-backed chair, painted light green, where we folded our clothes at night. (Atwood 148) Atwood’s portrayal of Grace paints a dramatic picture of the lives of the lower class during the 19th century. The example of textual evidence is more than four (4) typed lines. As a result, the writer introduces the quotation using a Complete Sentence Anchor. The writer then begins the quotation on a new line, indenting two (2) tabs. The quotation is NOT enclosed in quotation marks and maintains its double spacing format. A period is put at the completion of the quotation, and then the parenthetical documentation is placed within the parentheses. There is no punctuation after the close of the parentheses. The writer then resumes typing his argument on a new line. 16 Additional Examples Poetic Works The previous examples all used textual evidence taken from prose writing samples. Prose writing is the style of writing you would typically encounter in a novel, story, or article or while speaking. Essentially, it is language presented without any poetic embellishments. If you are citing a source written in poetry, you need to include some additional punctuation to denote where the lines of poetry break and what line numbers are being cited. The following examples detail how you would cite textual evidence from a poem and from a play written in poetry. Note the slight difference in both the structure of the quotation and the parenthetical documentation. Remember, regardless of what type of evidence you are citing, prose or poetry, the technique to introduce the quotation will remain the same as in the examples listed previously. 1. Poetry Example Example: Wordsworth begins his poem, “My heart leaps up when I behold / A rainbow in the sky” (Wordsworth 1-2). The writer’s words are separated from the quotation by a comma. The textual evidence appears enclosed in quotation marks. The backslash denotes a line break in the text of the poem and has a space on either side of it. The quotation is cited using the author’s last name and the line numbers. All of the citation information is enclosed in parentheses. Following the parentheses is a period to denote that the entire sentence has been completed. 2. Play Written in Poetry Example Example: In the play, Macbeth questions Angus about his new title: “The thane of Cawdor lives; why do you dress me / In borrowed robes?” (Shakespeare I.iii.108-109). The writer’s words are separated from the quotation by a colon. The textual evidence appears enclosed in quotation marks. The backslash denotes a line break in the text of the play. The quotation ends with a question mark so that is included in the quotation. The quotation is cited using the author’s last name, the act number (capitalized Roman numeral), the scene number (lower case Roman numeral), and the line numbers (regular numbers). All of the citation information is enclosed in parentheses. Following the parentheses is a period to denote that the entire sentence has been completed. 17 Citing Multiple Works by the Same Author If you are quoting multiple works by the same author, you must denote which source each example of textual evidence is pulled from when you are writing. This is done in the parenthetical documentation. In addition to listing the author’s last name and the page number for where the quotation appears, you must also list the title of the work. In the parenthetical documentation, list the author’s last name, the title of the work (properly punctuated), and the page number. If you are using an electronic source, the author’s last name and the title of the work are sufficient. Example: As Frost says himself, “Poetry is simply made of metaphor” (Frost, “The Constant Symbol” 786), in that each piece of advice the poem relays actually connects to a greater, more significant instruction about the ideal way to move through life. While the narrator is headed out to complete the basic and necessary chores associated with farm living, he also indicates that he will be taking the time to appreciate the beauty in the world around him because he plans to wait “…to watch the water clear…” (Frost, “The Pasture” 13) and pause to appreciate the newborn calf who is “…so young / It totters when [the mother] licks is with her tongue” (Frost, “The Pasture” 13). Following Frost’s own instruction on how to read poetry, this poem is clearly a metaphor for life as the eight short lines provide the reader with “…a momentary stay against confusion…” (Frost, “The Figure a Poem Makes” 777) to combat the hectic pace of life most individuals experience. Frost’s words are a reminder to take the time to enjoy the world, not just rush through it. 18 Formatting Your Paper Using MLA Style in Your Essay Writing MLA stands for Modern Language Association. Sutton High School uses the MLA format for essays and research papers; however, this style of formatting can be confusing if you are out of practice. On the following pages, you will find a step-by-step guide to setting up your paper in MLA format. This document also serves as a rough template for what your paper will look like once all the steps are completed. To organize your document in MLA style, simply follow the steps! ***Please note that these instructions correspond with Microsoft Word 2003. Newer versions of Word may have slightly different menu headings. Regardless of the version of Word you are using, your document should always adhere to the MLA guidelines for formatting. Use this guide and the other examples of essays throughout this booklet to confirm that your paper matches the specifications of MLA! *** 19 Doe 1 Jane Doe Teacher’s Name Course Name Due Date for Paper MLA Format MLA stands for Modern Language Association. Sutton High School uses the MLA format for essays and research papers. Follow the steps below when typing papers using MLA formatting. Step 1: Margins o Click on “File” in the standard toolbar o Click “Page Setup” o Change Top, Bottom, Left, and Right Margins to 1 Inch o Header/Footer Margins should be set to 0.5” Step 2: Page Numbers o Click on “View” in the standard formatting toolbar o Click on “Header and Footer” o Type your last name in the box provided o Hit the space bar o Click on the pound sign (#; “Insert Page Number”). This button will automatically number your pages. DO NOT type in the number 1 here; it will appear on all pages. o Click on the right align button that is in the formatting toolbar. You will see everything move to the right side of the page. o Click on the “Close” button. The page number will appear faintly on your computer, but it will print regularly. 20 Doe 2 Step 3: Double Spacing o Click on “Format” o Click on “Paragraph” o Change the line spacing to “Double” o Click on “OK” Step 4: Font o Click on “Format” o Click on “Font” o Make sure “Times New Roman,” “Regular,” and “12” are highlighted Step 5: Type Heading o Type your name o Type your teacher’s name o Type the title of the class o Type the date. Include the day first, then the month, then the year. Do not add any commas between these entries Step 6: Type Title o Click on the center align button in the formatting toolbar o Type the title of your paper o DO NOT underline your title or put it in bold print, italics, or quotation marks o DO NOT change the font size of your title o Hit enter and click on the left align button in the formatting toolbar Step 7: General Paper Rules o Begin typing the paper immediately after the title o DO NOT add any extra spaces before or after the title o DO NOT add any extra spaces between paragraphs 21 Preparing the Works Cited Page Examples of citations have been taken from MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers and the Sharon Public School’s Research and Writing Guide Please note that this is an abbreviated list. If the source you need to cite is not listed here, please consult the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers Books and Other Nonperiodical Publications Type of Entry Book with a single author In-Text Citation Format (Bronte 27) Works Cited Format Last name, first name. Title of book. City of publication: Name of publishing company, year of publication. Bronte, Emily. Wuthering Heights. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1992. Multiple books by the (Steinbeck, The Grapes of same author Wrath 78) (list alphabetically by book title) Steinbeck, John. The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights. New Book written by two authors Last name, first name, and first and last name of subsequent authors. Title (Eggins and Slade 168) York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976. ---. The Grapes of Wrath. New York: Penguin Books, 1992. of book. City of publication: Name of publishing company, year of publication. Eggins, Suzanne, and Diana Slade. Analysing Casual Conversation. London: Cassell, 1997. Book by three authors (Marquart, Olson and Sorensen 56) Last name, first name, first and last name, and first and last name of authors. Title of book. City of publication: publishing company, year of publication. Marquart, James W., Sheldon Ekland Olson, and Jonathan R. Sorensen. The Rope, the Chair and the Needle: Capital Punishment in Texas, 1923-1990. Austin: University of Texas Publishing, 1994. Book by More than Three Authors (Quirk et al 258) Last name, first name of first author, et al. Title of book. City of publication: Name of publishing company, year of publication. Quirk, Randolph, et al. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985. Book with no author (Encyclopedia of Virginia 789) Title of book. City of publication: Name of publishing company, year. Encyclopedia of Virginia. New York: Somerset, 1993. 22 Play or poem (plays and poems cite by section and/or line numbers) (Shakespeare III.ii.15-21) Example shown with Act.scene.linenumbers Last name, first name of author. Title of work. City of publication: Publishing company, year of publication. Shakespeare, William. The Taming of the Shrew. New York: Washington Square Press, 1992. Preface, Foreword or Afterword in a book (Sears 346) Last name, first name of the author. Section being cited. Title of overall work. By name of author of the overall work. City of Publication: Name of Publishing Company, Year of Publication. Page-numbers for selection. Sears, Barry. Afterword. The Jungle. By Upton Sinclair. New York: Signet, 2001. 343-347. A Work in an Anthology (Donne 243) Last name, first name of author. “Title of the selection from the anthology.” Title of the anthology. Ed. First and last name of editor. City of publication: Name of publishing company, year of publication. Page-numbers for selection. Donne, John. “Meditation 17.” Adventures in English Literature. Ed. Leopold Damrosch. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers, Inc. 1985. 149-216. Article in a reference book (“Noon” 845) “Title of Section.” Name of reference book. Edition number. Year of publication. “Noon.” The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. A Pamphlet (treat a pamphlet as you would a book, excluding the author if none is listed) (Renoir Lithograph 3) Title of pamphlet. City of publication: Name of publishing company, year of publication. Renoir Lithograph. New York: Dover, 1994. 23 Articles and Other Publications in Periodicals If the work is published by multiple authors, follow the formatting of names used for book resources Type of Entry Basic Article Entry in a Scholarly Journal In-Text Citation Format (Trumpener 1098) Works Cited Format Last name, first name of author. “Title of article.” Name of journal/publishing source. Volume number (year of publication): page-numbers. Trumpener, Katie. “Memories Carved in Granite: Great War Memorials and Everyday Life.” PLMA 115 (2000): 1096-1103. An Article in a (Smith 145) Scholarly Journal that Pages Each Issue Separately Last name, first name of author. “Title of article.” Name of journal/publishing source. Volume number.issue number (year of publication): page-numbers. Smith, Johanna M. “Constructing the Nation: Eighteenth-Century Geographies for Children.” Mosaic 34.2 (2001): 133-148. An Article in a (McNeilly 12) Scholarly Journal that Only Uses Issue Numbers Last name, first name of author. “Title of article.” Name of journal/publishing source. Volume number (year of publication): page-numbers. McNeilly, Kevin. “Home Economics.” Canadian Literature 166 (2000): 516. An Article in a Newspaper (Jeromack B7) Last name, first name of author. “Name of title.” Name of newspaper. Date of publication, edition: page-numbers. Jeromack, Paul. “This Once, a David of the Art World Does Goliath a Favor.” New York Times. 13 July 2002, late ed.: B7+. An Article in a Magazine (not a scholarly journal) (Mehta 18) Last name, first name of author. “Title of article.” Title of magazine Date of publication: page-numbers. Mehta, Pratap Bhanu. “Exploding Myths.” New Republic 6 July 1998: 1719. A Review (Updike 79) Last name, first name of reviewer. “Title of article.” Rev. Name source being reviewed, by name of author of work being reviewed. Title of source publishing review Date of publication: page-numbers. Updike, John. “No Brakes.” Rev. of Sinclair Lewis: Rebel from Main Street, by Richard Lingeman. New Yorker 4 Feb. 2002: 77-80. 24 An Editorial (if there (Gergen 72) is no author, begin with title of selection) Last name, first name of author. “Title of selection.” Editorial. Name of publishing source Date of publication: page-numbers. Gergen, David. “A Question of Values.” Editorial. US News and World Report 11 Feb. 2002: 72. A Letter to the Editor (Safer 4) Last name, first name of author. Letter. Name of publishing source Date of publication: page-numbers. Safer, Morley. Letter. New York Times 31 Oct. 1993, late ed., sec 2: 4. Miscellaneous Print and Nonprint Resources Type of Entry An Advertisement In-Text Citation Format (The Fitness Fragrance by Ralph Lauren 111) Works Cited Format Name of the product, company or institution. Advertisement. Publication information. The Fitness Fragrance by Ralph Lauren. Advertisement. GQ Apr. 1997: 111-112. A Lecture, a Speech, an Address, or a Reading (Atwood) Last name, first name of speaker. “Title of the presentation.” Name of meeting. Sponsoring organization. Location of event, city. Date of event. Atwood, Margaret. “Silencing the Scream.” Boundaries of the Imagination Forum. MLA Convention. Royal York Hotel, Toronto. 29 Dec. 1993. Personal/Telephone Interview (conducted personally) (Collins) Last name, first name of person being interviewed. Personal/Telephone interview. Date of interview. Collins, Phil. Personal interview. 8 June 1999. 25 Published Interview (Lansbury 75) Last name, first name of person being interviewed. “Title of interview, if one, otherwise put Interview with no quotation marks.” Source of published interview. By Name of interviewer. City of publication for source: Publishing company, year of publication. Pagenumbers. Lansbury, Angela. Interview. Off-Camera: Conversations with theMakers of Prime-Time Television. By Richard Levinson and William Link. New York: Plume-NAL, 1986, 72-86. Recorded Interview (Breslin) Last name, first name of person being interviewed. “Title of interview, if one, otherwise put Interview with no quotation marks.” Source of published interview. By Name of interviewer. Name of network. Call letters, city of station. Date of interview. Breslin, Jimmy. Interview. Talk of the Nation. By Neal Conan. National Public Radio. WBUR, Boston. 26 Mar. 2002. Television Interview (Childs) Last name, first name of person being interviewed. “Title of interview, if one, otherwise put Interview with no quotation marks.” Source of published interview. By Name of interviewer. Name of network. Call letters, city of station. Date of interview. Childs, Julia. Interview. The Oprah Winfrey Show. By Oprah Winfrey. ABC. WJAR, New York. 5 Apr. 1994. A Cartoon or Comic Strip (Trudeau 26) Last name, first name of artist. “Title of cartoon or comic strip.” Cartoon/Comic Strip. Name of publishing source Date of publication: page-numbers. Trudeau, Garry. “Doonesbury.” Comic Strip. Newark Star-Ledger 4 May 2002: 26. A Television or a Radio Program (“Frederick Douglass”) “Title of the individual episode or segment.” Title of the overall program. Title of series (if one). Name of network. Call letters, city of the local station (if any). Broadcast date. “Frederick Douglass.” Civil War Journal. Great Historical Heroes. Arts and Entertainment Network. A&E, Boston. 6 Apr. 1993. 26 A Sound Recording (Holiday) Last name, first name of artist. Title of the recording. Name of manufacturer, year of distribution. Holiday, Billie. The Essence of Billie Holiday. Columbia, 1991. A Film or Video Recording on DVD or VHS (It’s a Wonderful Life) Title of work. Dir. Name of director. Perf. Names of major performers in the work. Year of original release. Type of medium. Name of distributor, year of medium release. It’s a Wonderful Life. Dir. Frank Capra. Perf. James Stewart, Donna reed, Lionel Barrymore, and Thomas Mitchell. 1946. DVD. Republic, 2001. A Painting or Sculpture (Rembrandt van Rijn) Last name, first name of author. Name of artistic work. Name of institution that houses work/individual who owns work, city work is located in. Rembrandt van Rijn. Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. A Published Photograph of a Work of Art (Cassett 22) Last name, first name of author. Name of artistic work. Name of institution that houses work/individual who owns work. Source photograph is published in. By name of author of published work. City of publication: Publishing company, year of publication. Pagenumbers. Cassatt, Mary. Mother and Child. Wichita Art Museum. American Painting: 1560-1913. By John Pearce. New York: McGraw, 1964. 22. A Map or Chart (treat this as you would a book without an author, but add a descriptive label) (Michigan) Name of map or chart. Chart/Map. City of publication: Publishing company, year of publication. Michigan. Map. Chicago: Rand, 2000. 27 Electronic Publications How To Document Sources from the World Wide Web The following information has been obtained from http://www.mla.org/. The MLA guidelines on documenting online sources are explained in detail in the sixth edition of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (2003). Copies of this book are available in the Sutton Memorial High School Library. Copies are also distributed to sophomore students when their English classes cover the research paper unit. What follows here is a summary of the guidelines for documenting sources from the World Wide Web. For the complete MLA recommendations on web sources, please see the MLA Handbook. Sources on the Web that students and scholars use in their research include scholarly projects, information databases, the texts of books, articles in periodicals, and personal sites. Entries in a works cited list for such sources contain as many items from the list below as are relevant and available. When creating entries for the Works Cited page, include the following items in the order they appear on the list. If a source does not contain an item listed, skip it, and move on to the next item. 1. Name of the author, editor, compiler, or translator of the source (if given), reversed for alphabetizing and, if appropriate, followed by an abbreviation, such as ed. 2. Title of an article, poem, short story, or similar short work in the Internet site (enclosed in quotation marks) or title of a posting to a discussion list or forum (taken from the subject line and put in quotation marks), followed by the description Online posting 3. Title of a book, underlined 4. Name of the editor, compiler, or translator of the text (if relevant and if not cited earlier), preceded by the appropriate abbreviation, such as Ed. 5. Publication information for any print version of the source 6. Title of the Internet site (e.g., scholarly project, database, online periodical, or professional or personal site, underlined, professional or personal site with no title, a description such as Home page 7. Name of the editor of the site (if given) 8. Version number of the source (if not part of the title) or, for a journal, the volume number, issue number, or other identifying number 9. Date of electronic publication, or the latest update, of posting 10. For a work from a subscription service, the name of the service and—if a library or a consortium of libraries is the subscriber—the name and geographic location (e.g., city, state abbreviation) of the subscriber 11. For a posting to a discussion list or forum, the name of the list or forum 12. The number range or total number of pages, paragraphs, or other sections, if they are numbered 13. Name of any institution or organization sponsoring the site (if not cited earlier) 14. Date when the researcher accessed the source 15. URL of the source or, if the URL is impractically long and complicated, the URL of the site's search page. Or, for a document from a subscription service, the URL of the service's home page, if known; or the keyword assigned by the service, preceded by Keyword; or the sequence of links followed, preceded by Path. 28 Type of Entry Scholarly Project Information Database Personal Site In-Text Citation Format Works Cited Format (Victorian Women Writers Project) Victorian Women Writers Project. Ed. Perry Willett. May 2000. Indiana U. (Thomas: Legislative Information on the Internet) (Lancashire) Thomas: Legislative Information on the Internet. 19 June 2001. Lib. of 6 June 2002 <http://www.indiana.edu/~letrs/vwwp/>. ongress, Washington. 18 May 2002 <http://thomas.loc.gov/>. Lancashire, Ian. Home page. 28 Mar. 2002. 15 May 2002 <http://www.chass.utoronto.ca:8080/~ian/>. Online Book (Nesbit) Nesbit, E[dith]. Ballads and Lyrics of Socialism. London, 1908. Victorian Women Writers Project. Ed. Perry Willett. May 2000. Indiana U. 6 June 2002 http://www.indiana.edu/~letrs/vwwp/nesbit/ballsoc.html>. Poem Found Online (Nesbit) Nesbit, E[dith]. "Marching Song." Ballads and Lyrics of Socialism. London, 908. Victorian Women Writers Project. Ed. Perry Willett. May 000. Indiana U. 26 June 2002 <http://www.indiana.edu/~letrs/vwwp/nesbit/ballsoc.html#p9>. Article in an Online Scholarly Journal (Sohmer) Sohmer, Steve. "12 June 1599: Opening Day at Shakespeare's Globe." Early odern Literary Studies 3.1 (1997): 46 pars. 26 June 2002 http://www.shu.ac.uk/emls/03-/sohmjuli.html>. Article in an Online Magazine (Levy) Work from a Library Subscription Service (Youakim) Levy, Steven. "Great Minds, Great Ideas." Newsweek 27 May 2002. 20 May 2002 <http://www.msnbc.com/news/754336.asp>. Youakim, Sami. "Work-Related Asthma." American Family Physician 64 (2001): 1839-52. Health Reference Center. Gale. Bergen County Cooperative Lib. System, NJ. 12 Jan. 2002 <http://www.galegroup.com/>. Work from a Personal Subscription Service Posting to a Discussion List (“Table Tennis”) “Table Tennis.” Compton's Encyclopedia Online. Vers. 2.0. 1997. America Online. 4 July 1998. Keyword: Compton's. (Merrian) Merrian, Joanne. "Spinoff: Monsterpiece Theatre." Online posting. 30 Apr. 1994. Shaksper: The Global Electronic Shakespeare Conf. 23 Sept. 2002 <http://www.shaksper.net/archives/1994/0380.html>. 29 Building a Works Cited Page Is it a Works Cited or Works Consulted? Essentially, a Works Cited page and a Works Consulted page will contain similar information. Both pages will be made up of an alphabetical list of sources. The difference is that a Works Cited page will list all the sources that are quoted in the paper, while a Works Consulted page will list every source that you, as the writer, consulted, read, reviewed, or gleaned knowledge from while writing the paper. This includes every source listed on the Works Cited; after all, it would be impossible to cite a source without first consulting it! How do I list sources in a Works Cited/Works Consulted page? For both a Works Cited page and a Works Consulted page, the sources are listed alphabetically by the first word in the entry (omitting the words the, a, or an). Remember, if you do not have an author for a source, you start the entry with the next available piece of information, typically the title of the work. A sample Works Cited page is listed on the next page. Note that the writer only lists the sources; you do not create a bulleted or numbered list. If you are creating a Works Consulted page, almost everything remains the same, only the title of the page changes. Instead of titling the page Works Cited, you would title it Works Consulted. What will my Works Cited or Works Consulted page look like? To see an example of a properly structured Works Cited/Works Consulted page, please see the following page in this booklet. This example features a Works Cited page with a variety of resources including 1. A work from an InfoTrac search engine with a volume number 2. A selection in a larger work by one specific author 3. Multiple works by the same author 4. A work with four or more authors 5. A website 6. A work from an InfoTrac search engine with a volume and issue number 7. A work with multiple authors 8. A basic book entry 9. A work from an anthology 30 Corsa 21 Works Cited Edwards, A.S.G. “Paganism in Arthurian Romance.” The Review of English Studies 47 (1996): 403-404. Expanded Academic ASAP. InfoTrac. Sutton Memorial High School Library, MA. 20 Oct. 2004. <www.galegroup.com>. Frost, Robert. “The Constant Symbol.” Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays. New York: The Library of America, 1995. 786-791. ---. “The Figure a Poem Makes.” Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays. New York: The Library of America, 1995. 776-778. ---. “The Pasture.” Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays. New York: The Library of America, 1995. 13. Guerin, Wilfred, et al. A Handbook of Critical Approaches to Literature. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. Johnston, Ian. “Introduction to Macbeth.” Mr. William Shakespeare and the Internet. Ed. Terry A. Gray. 4 Mar. 2005. Palomar College. 18 Jan. 2006 <http://www.mala.bc.ca/~johnstoi/eng366/lectures/macbeth.htm>. Lentricchia, Frank. “Experience as Meaning: Robert Frost’s ‘Mending Wall.’” The CEA Critic 34.4 (1972): 9-11. Literature Resource Center. InfoTrac. Sutton Memorial High School Lib. System, MA. 6 June 2007 <http://www.galegroup.com>. Spivack, Charlotte, and Roberta Lynne Staples. The Company of Camelot: Arthurian Characters in Romance and Fantasy Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, Inc., 1994. Stoker, Bram. Dracula. New York: Bantam Books, 1981. Wilde, Oscar. “The Importance of Being Earnest.” Adventures in English Literature. Ed. Leopold Damrosch. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publisher, 1985. 632-668. 31 Appendix A Sample Research Paper Strieby 1 Christina Strieby Dr. Seiden Whitman, Dickinson, Frost 21.832 14 June 2007 Frost’s Poetry as Evidence of Man’s Need for Companionship Backed by his extensive collection of poetry, Robert Frost is a writer commonly associated with man’s desire for solitude. The seeming simplicity and the individualized subject matter of Frost’s poetry is part of his universal appeal for so many readers. However, when one investigates more deeply into Frost’s collection of work, the poems that originally appear so simplistic begin to take on a more developed and detailed scope and meaning. While on the surface it appears that the trials and travails of the individual are Frost’s major focus, it is also possible to argue that, despite an overriding tone of isolation in so many works, the poetry of Robert Frost speaks universally about man’s need and desire for companionship within the world around him. Upon deeper examination of the individual works, it becomes clear that Frost’s work, with its common language and familiar imagery, is much more complex than many reader first assume. This is true for one of Frost’s most famous poems, “Stopping by Woods.” In his analysis of this work, one critic states, But, as experienced readers of this poem know, “Stopping by Woods” has a disconcerting way of deepening in dimension as one looks at it, of darkening in tone, until it emerges as a full-blown critical and pedagogical problem. One comes to feel that there is more in the poem than is given to the senses alone. But 32 Strieby 2 how is one to treat a poem which has so simple and clear a descriptive surface, yet which somehow implies a complex emotional attitude? (Ogilvie). Similarly, this is the case for one of his first published works, “The Pasture,” a poem that while on the surface seems to promote man’s tendency for isolation, actually displays a longing for companionship. This poem opens with an individual figure about to embark on what at first appears to be commonplace farming chores: “I’m going out to clean the pasture spring; / I’ll only stop to rake the leaves away” (Frost, “The Pasture” 13). This correlates with the typical assumption of theme for Frost’s poetry: a solitary man beginning a solitary project. However, as one examines the poem more closely, the line, “I sha’n’t be gone long—You come too” (Frost, “The Pasture” 13), which is repeated twice in the short poem, becomes more important in its intended meaning. By asserting this direct request, “You come too” (Frost, “The Pasture” 13), Frost, through his speaker, is offering a bold invitation, almost a demand, that someone, be it another person, the spouse or friend of the narrator, or even the audience of the poem itself, come along on the excursion that is about to be undertaken. Through his narrator, Frost is making a plea for company, stating that the speaker would appreciate some companionship, even if he is only going out to complete mundane chores. While “The Pasture” is a request for company and companionship during completion of mundane farming chores, it is also a statement about the needs and desires of every man and the very nature of humanity. As stated previously, part of Frost’s popularity as a writer stems from the accessibility of the general people to his work. It is because of this accessibility that the poetry of Robert Frost is so significant because, sometimes unbeknownst to the reader, “the more effectively he can use it as a medium for the symbolic representation of realities in other areas of experience” (Lynen 21), the greater meaning a work will carry. As such, “The Pasture” is not 33 Strieby 3 merely a poem about farming life and chores, but instead a microcosm of the world as a whole and man’s desire for companionship as he progresses through the stages of life. The phrase, “You come too” (Frost, “The Pasture” 13) is man’s assertion for company as he grows through age and time, as it is companionship that makes life, mundane chores and all, enjoyable. It is also Frost’s encouragement, through the voice of a nameless narrator, to enjoy the small pleasures in life as time progresses because without appreciation for smaller elements the world has to offer, too often life will pass the individual by without that person ever finding true contentment. As Frost says himself, “Poetry is simply made of metaphor” (Frost, “The Constant Symbol” 786), in which each piece of advice the poem relays actually connects to a greater, more significant instruction about the ideal way to move through life. While the narrator is headed out to complete the necessary chores, he also proves through his words that he will be taking the time to appreciate the beauty in the world around him when he waits “…to watch the water clear…” (Frost, “The Pasture” 13) and when he pauses to appreciate the newborn calf who is “…so young / It totters when [the mother] licks is with her tongue” (Frost, “The Pasture” 13). Following Frost’s own instruction on how to read poetry, this poem is clearly a metaphor for life as the eight short lines provide the reader with “…a momentary stay against confusion…” (Frost, “The Figure a Poem Makes” 777) to combat the hectic pace of life most individuals experience and it is a reminder to take the time to enjoy the world, not just rush through it, preferably with someone along for the experience. 34 Strieby 4 Works Cited Frost, Robert. “The Constant Symbol.” Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays. New York: The Library of America, 1995. 786-791. ---. “The Figure a Poem Makes.” Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays. New York: The Library of America, 1995. 776-778. ---. “The Pasture.” Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays. New York: The Library of America, 1995. 13. Lynen, John F. The Pastoral Art of Robert Frost. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960. Ogilvie, John T. “From Woods to Stars: A Pattern of Imagery in Robert Frost’s Poetry.” South Atlantic Quarterly LVIII.1 (1959): 64-76. Literature Resource Center. InfoTrac. Sutton Memorial High School Lib. System, MA. 6 June 2007 <http://www.galegroup.com>. 35 Appendix B Presearch Name: Class: Class Topic: Read one selection about your area of interest. On the organizer below, record possible research topics, information about these topics, and ideas and questions you have. Be sure to explore topics that you would like to study in depth. Area of Interest: Possible Topic Information, Ideas, and Questions 36 Appendix C Developing the Research Topic Name: _____________________________ After finishing your presearch, examine what you have written and choose one topic as the focus of your research study. Write that topic in the oval below. Think of categories related to your topic as you build your concept map. Group what you know (prior knowledge) and what you want to find out (questions) around each category. Sample: Category Question Knowledge My Topic Category Concept Map My Topic 37 Knowledge Developing the Research Topic Continued From your concept map, write several possible researchable questions related to your assignment. Star () the question you find both worthy of answering and of greatest interest. Sample A Sample B Teacher Question: How does your tribe pass on its values and beliefs? Class Topic: Native American Tribes Possible Researchable Questions: 1. How have other tribes impacted the Hopi Nation? 2. What was the impact of European migration into the Hopi territory? 3. How are the Hopi ceremonies and rituals used today? Teacher Question: How might biogenetic research affect your topic? Class Topic: Human Body Possible Researchable Questions: 1. What causes optical illusions? 2. Do people become less nearsighted as they age? 3. Are men more likely to be colorblind than woman? Teacher Questions: _____________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ Possible Researchable Questions for the Study of My Topic: ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ 38 Appendix D Outline for Essay Writing I. Introduction: A. Hook B. Basic Information 1. Title 2. Author 3. 2-3 sentences of plot summary II. First Point: A. Supporting Details: 1. 2. B. Textual Evidence/Quotation: 1. III. Second Point: A. Supporting Details: 1. 2. B. Textual Evidence/Quotation: 1. 39 IV. Third Point: A. Supporting Details: 1. 2. B. Textual Evidence/Quotation: 1. V. Fourth Point: A. Supporting Details: 1. 2. B. Textual Evidence/Quotation: 1. VI. Fifth Point: A. Supporting Details: 1. 2. B. Textual Evidence/Quotation: 1. VII. Conclusion: 40 Appendix E Name: __________________________________ Outline for Essay Hook: Basic Info: Title, Author and Plot Thesis Statement: Topic Sentence: 1 2 3 Topic Sentence: 1 2 3 Topic Sentence: 1 2 3 Thesis Statement: 41 Appendix F Topic: Introduction Hook: Basic Information: Thesis Statement: First Point: Body Supporting Evidence: Textual Evidence: Second Point: Body Supporting Evidence: Textual Evidence: 42 Third Point: Body Supporting Evidence: Textual Evidence: Fourth Point: Body Supporting Evidence: Textual Evidence: Conclusion Information Wrap Up: 43 Works Consulted The following is a list of resources consulted during the development of this writing guide. Borrelli, Alison, et al. Sharon Public Schools Grades 6-12 Research and Writing Guide Based on MLA Format. Sharon: Sharon Public Schools, 2005. Gibaldi, Joseph. MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers. 6th ed. New York: The Modern Language Association of America, 2003. Nottage, Cindy, and Virginia Morse. IIM Independent Investigation Method: 7 Easy Steps to Successful Research for Students in Grades K-12. Epping: Active Learning Systems, LLC, 2005. Raimes, Ann. Keys for Writers: A Brief Handbook. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996. Sutton Memorial High School: Student/Parent Handbook 2007-2008. Sutton: Sutton High School, 2007. 44