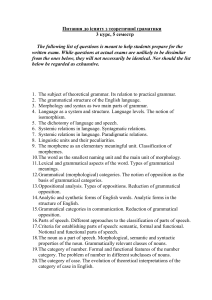

Lectures in Theoretical Grammar

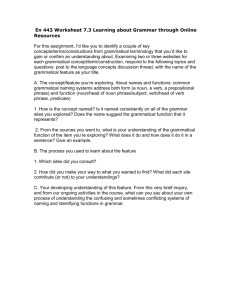

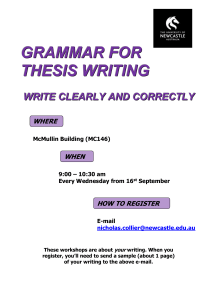

advertisement