Situating your argument

advertisement

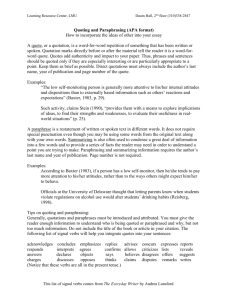

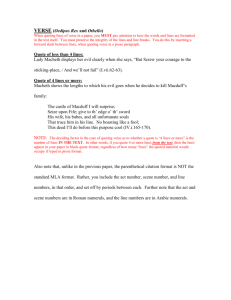

Situating your argument Texts (the ones you read and the ones you create) do not exist in a vacuum. They are always rhetorical, which means: they emerge out of a situation which requires discourse, they continue conversations that have already begun elsewhere on the topic which is already being discussed, they constitute a “move” in that ongoing discussion, and they enable both further later conversation and action (certainly mental and possibly physical). If you wish your “move” in the conversation (the argument you’re making via your text) to be effective, you must acknowledge the discussion that’s come before and anticipate the discussion that will come after. In other words, you must situate your argument in the context of the ongoing social discussion of the topic you’re addressing. Nurses are under increasing pressure to contextualize their “moves” in practice in the context of previous discussions in scientific research – this is the essence of evidence-based practice. Nurses are also under pressure to contextualize their “moves” in the social, economic, political, and ethical climate in which their practice is situated. Situating a text you create, then, requires some conceptual and technical skills. Technically, you will need to know how to effectively quote, paraphrase, and summarize (while avoiding patchwriting). You’ll also need to know how to cite the previous published literature that addresses your topic. Whether quoting, paraphrasing, or summarizing, you must credit the author(s) for the idea, using a proper reference style! Citing Citing: providing specific publication information about a text that made a previous “move” in the conversation. This gives the reader a little bit of information (title, author, publication) about where you found your information and allows people to track the text down for themselves to check the fairness and accuracy of your use of the source material. A complete citation includes two components: in-text cite: a marker within the text itself that “points” to the specific information about where to find that article and that ties that article to a specific idea or small set of ideas; works cited list: the full citation information, usually located at the end of a paper, that provides the full “location” information of the cited work. TASK: establish an EndNote citation management account: http://www.myendnoteweb.com/EndNoteWeb.html TASK: Add a correct in-text citation in APA format to this sentence: Freshmen college students face many distractions and disruptions that impair their ability to get adequate sleep TASK: Convert this in-text citation into correct APA format: Brown discusses numerous challenges to good community among nurses and between nurses and doctors. Teasing, she claims, is one common way that these challenges are mediated (Brown, Critical Care; p. 49; 2010) If you write several sentences in succession that all derive from the same source, it’s best to put the citation first, and then make it obvious that the rest of the sentences all are from the same source: Benjamin Franklin was very interested in efficiency and thrift. In fact, he said, “A penny saved is a penny earned” (Franklin, Poor Farmer’s Almanac 37; Silence Dogood 48). According to Franklin, people could contribute to the economic efficiency of their households by eating apples everyday (a cheap, common foodstuff in colonial America) and by getting to bed early and getting up early in the morning so that they could avoid having to use candles. In his scientific treatise, “Electromagnetic Energy,” he also advocated that people supplement their household energy needs (at that time, usually supplied by firewood) by crafting ingenious devices to harvest electrical energy made from kites and keys (89). Quoting Quoting: lifting the exact words someone else has written, verbatim, from a text that has previously entered the discussion. Quoting should only be used under certain, very specific conditions, and there are specific technical rules that quoting must follow in order to avoid plagiarism. Use the “sandwich method” – assume the “meat” of your quote needs to be sandwiched between two sentences YOU write. The sentence before the quote must explain who is speaking and show why the quote is salient/relevant to YOUR text. The sentence after the quote must explain what you believe the quote is saying and explain why it is important to the point YOU are making. Explanatory framing: As a general rule, the quotations that need the most framing are those that are hard for readers to process: they are long, they contain complex ideas, they contain ideas that are likely to be unfamiliar to your audience, they are filled with details or jargon. Remember: Your framing of a quotation is your chance to use the quotation for YOUR rhetorical purposes. Since quotes rarely truly speak for themselves, don’t forfeit the opportunity to make the quote work for you! Quoting is not a strategy you use when you don’t want to do your own writing. It should be used sparingly, ONLY when the situation calls for it. Quoting is useful for situations when you need to be able to say, “look, you don’t have to take my word for it! This is exactly what s/he/it says!” Quoting is quite unusual in scientific articles; as you start to write this kind of article in other courses, you’ll want to avoid quoting. When do you quote? when the actual wording of the passage is significant when you are providing evidence of a textual phenomenon to support a claim you’re making about a text Doctors often disregard the feelings of nurses when talking to patients, saying “if you have to blame someone, blame her” (TASK: INSERT APA intext cite) “Only as much of the source as necessary should be quoted and the sentence should be phrased in such a way that the quoted words fit logically, as grammatical parts of it.”1 1. Chicago Manual of Style, p. 285. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 1982. TASK: Convert the in-text cite and the bibliographic reference above to APA style. Paraphrasing Paraphrasing: Representing someone else’s specific ideas from a previous “move” in the discussion using your own words. When do you paraphrase? When you want to represent the author’s original ideas in nearly as much detail as they do, but the actual wording of their ideas is not important. Common paraphrasing problem: patchwriting. This is basically lifting a “quote” (that you do not signal as such with quote marks) from a source text and placing it largely intact within your own text, perhaps changing one or two words in the sentence. Optimal paraphrase will integrate into your own rhetorical purpose and will express the detailed ideas of a source text in entirely your own words. Summarizing Summarizing: Articulating the main overall argument (thesis) someone else has made using your own words. Rhetorically, when you summarize, you must do two things, and they are in tension with each other: You need to provide a “fair” representation of the previous author’s ideas You need to position that previous author’s ideas in a way that will enable you to make your own point/move most effectively. It’s easy to distort someone else’s ideas when you’re trying to use them to make your own point. But it’s also easy merely to “list” someone’s ideas if you’re not sure how to use them to support your own move in the conversation (particularly if you don’t yet know what move you intend to make). What’s most important is that you realize summaries are rhetorical acts (i.e., acts of PERSUASION). Texts that are the length of a newspaper article or longer contain lots of ideas, and in summarizing, you are selecting some of those ideas and leaving others out. Your selections constitute your ARGUMENT for what is the most important to pay attention to/respond to…and they imply that what you’ve left out is not important (at least in this rhetorical situation). TYPICAL PROBLEMS WITH SUMMARIES Biased summaries In her book, Critical Care, Brown represents doctors as arrogant, overpaid, and unsympathetic to patients. She represents patients as ignorant, irrational, and needy. Danger: You’re not showing your authority figure that you’ve read and thoroughly thought about the complexity of the book. You’re also not demonstrating your willingness to be fair-minded and to consider all points of view. Closest Cliché summaries (you mistake the author’s view for a clichéd view) In her book, Critical Care, Brown shows how nurses perform the menial tasks of medical care. Danger: You’re raising the strong suspicion you haven’t read the book or, if you have, that you didn’t understand what it said. List summaries In her book, Critical Care, Brown discusses why she decided to stop being an English professor and go into nursing. She describes a leg injury she has early in her career as a new nurse. She describes some of the patients, doctors, and fellow nurses she encounters during her first year of nursing practice. She also tells some of the things that happen to various individual patients during this year. At the end of the book, she recommends that people who want pianos should buy them right away in case they get cancer and die. Danger: Although it will be clear you’ve read the entire book, you’re not demonstrating that you understand it, and can evaluate what’s more important and what’s less important. You’re also being incoherent. A good summary is unbiased and yet focused toward the issue you wish to address. It will eventually be useful in helping you argue your claim: In her book, Critical Care, Brown addresses the issue of nurses’ power in a complex way, showing how nurses’ power is located within the organizational structure of the hospital setting. Within this setting, she claims that nurses’ power is constrained by doctors’ orders, by the way the various departments are organized in the hospital, and even by the authority of more senior nurses in the organization. For example, she tells how she must navigate the logistic infrastructure of the hospital to schedule a medical test and then successfully prepare and deliver a patient for the test so that doctors will have the results they need to plan the next phase of that patient’s treatment. As this anecdote also shows, however, nurses have a great deal of power to ease patient discomfort with the medical procedures they face. Brown succeeds in coordinating this patient’s care so that he doesn’t have to fast for the procedure more than once.