Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

advertisement

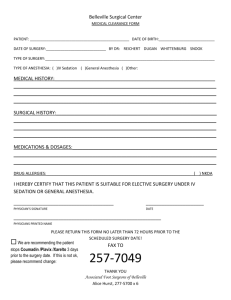

GUIDELINES FOR MANAGEMENT OF “PONV" (Reviewer: Dr. Salah N. El-Tallawy) Introduction: PONV is an unpleasant experience that patients often rate it worse than postoperative pain. It occurs in about 20-30% of patients. PONV may be induced through various pathways; however, one stimulus may act on more than one pathway. Scope of the problem: While PONV is generally self-limited, it can lead to rare, but serious medical complications such as aspiration of gastric contents, suture dehiscence, esophageal rupture, subcutaneous emphysema, or pneumothorax. PONV may delay patient discharge from PACU, and leads to unexpected hospital admission. Goals of Guidelines 1- Identify the primary risk factors for PONV. 2- Reduce the baseline risks for PONV, 3- Identify the optimal approach for prevention and therapy, 4- Determine the optimal choice and timing of antiemetic administration, 5- Identify the most effective antiemetic therapy regimens. Risk Factors (PONV): 1. Patient-specific risk factors: a. Female sex b. Nonsmoking status c. History of PONV/motion sickness 2. Anesthetic risk factors a. Use of volatile anesthetics within 0 to 2 h b. Nitrous oxide c. Use of intra- and postoperative opioids 3. Surgical risk factors a. Duration of surgery (each 30-min ↑ in duration ↑ PONV risk by 60% b. Type of surgery (laparoscopy, ear-nose-throat, neurosurgery, strabismus, laparotomy, plastic surgery) breast, Treatment Strategy: 1. Strategies to Reduce Baseline Risk a. Use of regional anesthesia b. Use of propofol (TIVA) c. Avoidance of volatile anesthetics and nitrous oxide d. Minimization of intra- and post-operative opioids e. Minimization of neostigmine f. Use of intraoperative supplemental oxygen g. Use of hydration 2. Titrate preventive measures according to the patient’s needs a) Low risk: The use of prophylactic antiemetics is rarely justified when the patient’s risk is low, e.g. 10%-20%. However, the use may be justified if: o This is a patient’s preference, o There are concerns about complications due to vomiting. b) Moderate risk: One or two antiemetic measures are often appropriate. o One approach could be TIVA. o The use of 4 mg dexamethasone after the induction of anesthesia. o Minimize opioid consumption by (NSAIDs, lidocaine, or ketamine). c) High risk: Avoidance of general anesthesia and minimization of perioperative opioids may be the most effective approach (e.g. peripheral nerve block, spinal anesthesia). However, if a general anesthetic is needed: o A TIVA with 4 mg dexamethasone. o An additional can be recommended: e.g. 12.5-25mg promethazine, 31.25-62.5 mg dimenhydrinate, or 25-50 mg Metoclopramide. An inhalational anesthetic can be used with an additional antiemetic e.g. the use of a serotonin-antagonist. Finally, stimulation of the P6 may be another option given that its efficacy has been demonstrated for the prevention of PONV. 3-Rescue without delay Rescue treatments are interventions that have not been applied before, or where the half life suggests that it’s no longer active. Serotonin-antagonists, if they were not given in the OR, may be first choice in the PACU because of their lack of sedative side effects. Also, the addition of dexamethasone to dolasetron or haloperidol might increase the overall risk reduction. Table 1: Antiemetic Doses and Timing for Administration in Adults Drug Dose Timing Ondansetron 4–8 mg IV At end or surgery Dolasetron 12.5 mg IV At end or surgery Granisetron 0.35–1 mg IV At end or surgery Tropisetron 5 mg IV At end or surgery Dexamethasone 5–10 mg IV Before induction Droperidol 0.625–1.25 mg IV At end or surgery Dimenhydrinate 1–2 mg/kg IV At end or surgery Ephedrine 0.5 mg/kg IM At end or surgery Prochlorperazine 5–10 mg IV At end or surgery Promethazine 12.5–25 mg IV At end or surgery Scopolamine TTS 4 h before end of surgery Table 2: Antiemetic Doses for Children Ondansetron 50–100 µg/kg up to 4 mg Dolasetron 350 µg/kg up to 12.5 mg Dexamethasone 150 µg/kg up to 8 mg Droperidol 50–75 µg/kg up to 1.25 mg Dimenhydrinate 0.5 mg/kg Perphenazine 70 µg/kg