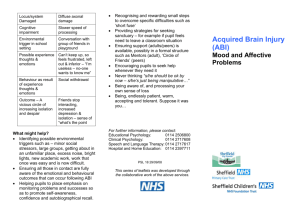

Understanding and misunderstanding ABI

advertisement