William Freund - Pace University

advertisement

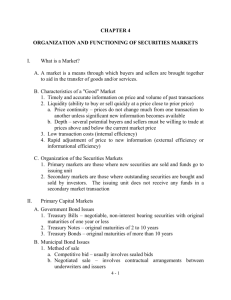

OCCASIONAL PAPERS September 2002 Reflections on a Lifetime in the Securities Industry by William C. Freund, Ph.D. Director, William C. Freund Center for the Study of Securities Markets Lubin School of Business Pace University This lecture was presented to faculty and students at the Center for Global Finance “At the Center” lunchtime meeting at Pace University on April 24, 2002. REFLECTIONS ON A LIFETIME IN THE SECURITIES INDUSTRY By William C. Freund, Ph.D. William C. Freund is Director of the William C. Freund Center for the Study of Securities Markets at the Lubin School of Business, Pace University. Reflections Introduction I joined the New York Stock Exchange as senior vice president and chief economist in 1968 and remained in that post for nearly twenty years. Following that tour of duty, I fulfilled my lifetime ambition to teach and spent another fifteen years at Pace University as the NYSE Professor of Economics. In academia, I remained in close touch with the securities industry by serving as the director of the Pace University's Center for the Study of Equity Markets (recently renamed the William C. Freund Center for the Study of Securities Markets). Over the past decade, the Center has organized a highly-regarded annual securities industry conference attended by some of the best and brightest of Wall Street practitioners. In sum, I have spent some thirty-five years as a participant and observer of the financial services industry. My comments here are highly personal and reflect my involvement during a time of unprecedented industry changes. Competition Comes to the NYSE One of the principles I learned as a graduate student in economics was the power of fundamental economic ideas and principles. As a practicing industry economist, this power was amply confirmed. I came aboard at the NYSE just at the time when the US Department of Justice filed its famous brief with the SEC to abolish fixed minimum commission rates on brokerage transactions. For some 200 years, ever since the Buttonwood agreement established the NYSE, commission rates were fixed by the members of the NYSE, more recently with the explicit consent of the SEC. (In practice, SEC approval was a formality.) Commissions were fixed per so-called "round lot" of 100 shares. If the commission on a 100 share order was $35, then 1,000 shares would cost $350, and 10,000 shares, $3,500. Of course, 1,000 shares did not cost ten times as much as 100 shares to execute and even 10,000 shares cost only fractionally more. With pension funds, insurance companies, mutual funds, and other institutions becoming more active and transacting larger trades, the round lot commission schedule became what some called "a license to steal." But there is a fundamental rule of economics: when price competition is prohibited, service competition and other competitive pressures inevitably emerge. Brokers began to offer "free" such services as research and market making or block positioning of larger orders. If an institution wanted to sell a big block, the broker-dealer would take a loss on the block transaction as a way of rebating commissions. Since rebates were allowed among brokers, some institutions like Prudential Insurance formed their own brokerage subsidiaries to recapture commissions. Other commissions were simply moved around the industry to pay for research and various non-execution services. 1 Reflections Given the proliferation of these "soft dollars," the SEC recommended replacing fixed minimum commission rates by rates set competitively in the marketplace. The NYSE did come forward in support of some discounts on large volume trades but the proposal was too little too late. The NYSE's members failed to understand the immense power of competition and that they could no longer stem the powerful tide of competition. In the end, good economics has a way of prevailing over artificial price fixing. By 1975, after extensive hearings, the SEC declared rates fully open to competition. The Role of the In-House Economist As a paid hand, the task fell to me to marshal all the arguments favoring the retention of fixed commission rates. I was confronted by a major ethical dilemma. My professional training and convictions favored competition; yet my paycheck required the defense of fixed rates. Perhaps I should have resigned and stood on principle. It is a source of some mental conflict to this day. At the time, I thought of my wife and children and the difficulty of matching my fascinating job and exciting responsibilities. I rationalized the situation. In our society, even criminals have the right to defense and, until then, fixed rates had been absolutely legal. I worked closely with the Exchange's lawyers who, I believe, never thought about their conflict. Nor did the economic consulting firm we retained, National Economic Research Associates. They had extensive experience and expertly represented many public utilities in rate cases. They now constructed a complex case for retaining fixed rates in the securities industry. The argument was that it was an industry with such heavy fixed costs that competition would lead to "destructive competition," leaving only a few oligopolistic survivors. Arguing the other side, the Department of Justice marshaled some of the best economic talent around, including Professors William Baumol and Paul Samuelson. We spent over $1 million on our economic consultants (at a time when a million was real money!) a fee they earned by delaying fully competitive rates for nearly seven years. But before the battle was lost, the clear-thinking president of the New York Stock Exchange, Bob Haack, had enough. And here hangs a tale of great courage. On a Friday afternoon, when the Exchange was thick in battle to keep fixed rates, Bob Haack handed me a speech he had written himself for delivery the following Monday before the prestigious Economic Club of New York. I took the speech home and when I read it, my teeth nearly fell out! Here was the president of the Big Board attacking fixed rates as an outdated anomaly which could not continue because it was not in the best long-run interests of the securities industry itself. In an era of increasing institutionalization of trading, he said, fixed rates were bound to lead to many underhanded or under-the-counter circumventions. I was shocked. I called Bob Haack at home and told him that if he proceeded to give this speech, he would surely be fired the next day. (At that time, the 2 Reflections NYSE was like a private club, run by the members for the benefit of the members.) I will never forget Bob Haack's answer: "Sometimes a man has to do what is right, whatever the consequences." Bob Haack did give his speech. The next morning it was the featured front-page story in The New York Times. He was not fired for fear of another embarrassing headline and he served out the remaining year of his contract largely as a lame duck. But he left with his integrity in tact. His expectation that the industry would benefit from competitive rates was vindicated by subsequent events. Commissions became fully competitive on May 1, 1975. NYSE members used to call that May Day. They must have thought it was a Communist conspiracy rather than the laws of economics at work. "Creative Destruction" Confirmed Once free-for-all competition was unleashed, major structural changes were the inevitable result. Commission rates became "unbundled," with executions often done at five cents per share or less. Discount brokers sprang up and specialized in bare bones executions, exclusive of any charges for research or other services. New competitive opportunities arose for markets and firms as a result of competition. The industry discovered new ways to enhance productivity by automating processes, rationalizing the clearing and settlement of security transactions, and generally reducing unit costs. New competitive ideas proliferated. Instinet became a powerhouse in matching buy and sell orders, as did the later so-called ECNs or electronic communications networks. New names such as Island ECN and Archipelago appeared on the horizon. Many smaller brokerage firms, lacking adequate resources for competition, either merged or closed their doors. But competition among the larger firms remains exceedingly intense. The great Austrian and Harvard economist Joseph Schumpeter spoke about "creative destruction." The process of innovation and entrepreneurship, he argued, not only creates new opportunities for new competitors but also destroys old industries and older ways of doing business. Polaroid is in bankruptcy because of the availability of one-hour film developing almost everywhere and, more recently, the invention of digital or instantaneous photography. Creative destruction is a real force, I have seen it at work in the securities industry, where it continues to foster innovation and unprecedented competition for the general benefit of investors. 3 Reflections What a Difference One Person Can Make During my Big Board career, I reported directly to four different CEOs -- Bob Haack, Jim Needham, Mil Batten, and John Phelan. Most recently, Chairman Dick Grasso has been at the helm. When I worked with him on the Exchange staff, I recognized a very quick and savvy mind at work. I was not surprised when, on reaching the top (a first ever for an NYSE staff member), he displayed an uncommon talent to innovate and automate the Exchange. Indeed, with an annual expenditure of around $400 million on automation, the NYSE may be the biggest ECN around. I have seen what a difference one person at the top of an organization, even a large one, can make. I offer this anecdotal example. One day, in the 1970s, a former Wall Street Journal reporter came to my office with a dynamite new idea: In the past, options were not standardized but were tailor made by dealers as to maturity and price. The new idea was to standardize options and to trade them like stocks. I took the proposal to the chairman, Jim Needham (an accountant and former SEC commissioner). His response was totally negative. He gave me an earful. Under his watch, the NYSE would never be turned into a Las Vegas type gambling casino. He would never jeopardize the solid gold reputation of the institution. Indeed, he said, I forbid your Research Department from studying the idea. The cost of this impulsive decision proved astronomical for the Big Board as options trading went to Chicago and took off. Soon, some options contracts traded a larger volume than the underlying stock at the NYSE. What's more, the NYSE could never recapture that business. After Needham was fired by the Board of Directors (for a variety of reasons), William Batten, known to most as Mil, took over. He was a most astute businessman, who understood the stakes. Having come from retailing, he argued the Exchange should be more than a one product store. So he set up the NYFE (New York Futures Exchange) and started to offer options. But the securities industry is subject to another economic fact of life: Orders will flow to the market with the best prices and liquidity. Once orders flowed to the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE), that venue became the best market and attracted order flow. In other words, liquidity begets liquidity. It's a Catch-22 for an upstart -- orders flow to the best market, which perpetuates the liquidity of that market. Given these circumstances, it became difficult, and ultimately impossible, to correct the mistake of an earlier chairman. The New York Stock Exchange missed the boat largely, I think, because the chairman lacked vision. 4 Reflections The Value of Economic Training Mil Batten did much to lay the groundwork for a more competitive, more automated Exchange. One of his accomplishments was to recognize the importance of meeting peak load demands. Chairman Batten had studied economics as a graduate student and he remembered some principles of public utility economics. In one of his courses, he told me, he learned that utilities must have spare capacity to meet peak demands. You cannot ask consumers in July to hold off running their air conditioners until November when power supplies are ample. Similarly, the securities industry must have excess capacity to meet unexpected peak load demands. Much like the demand for electricity, the demand for stock transactions must not be delayed. The Exchange's new planning was based on the ability to handle a billion shares a day when actual volume was running around 100 million. Indeed, many members objected to management wasting their money in preparing for an unrealistic volume of trading. This protest quickly vanished as volume on the Exchange escalated sharply. Today, the Exchange handles 1.5 billion shares a day routinely and has the capacity to handle 10 billion shares on a sustained basis. A good grounding in economics is invaluable for exercising real entrepreneurial leadership. A Sense of Humor I'd like to share one other conclusion of a lifetime in the securities business: the benefits of retaining a sense of humor even in stressful and contentious situations. I remember the advice of my wife, to step back and see a situation in all of its humorous perspective. Often I would break a tense situation, or maintain my internal balance, by laughing at the human condition. "That reminds me of a story" became my occasional refrain. My survival and my sanity at the Exchange was boosted by reflecting on the foibles of mankind. I learned to appreciate the old adage: Take your job seriously, but never yourself. By the way, there are also some hilarious situations at universities. Even now, I laugh when I see some of the journal articles in finance and economics, which are totally detached from reality. But, of course, they help people get tenure! 5 Reflections This is the Greatest Country in the World Finally, I must recognize this wonderful country, which gave me the opportunities I had. It was Winston Churchill who said: "Americans always do the right things -- after they have exhausted all other alternatives." I came to this country at age eleven, a refugee from Nazi Germany. Our family of four arrived without knowing any English and with seven dollars in our collective pockets. I started out shining shoes on the streets of uptown Manhattan, in the Washington Heights district, at five cents a pair. Where else would I have had the wonderful opportunities to get an education and to participate in the upper echelons of American business? America, with all its blemishes, remains a unique country of opportunity. I continue to direct the William C. Freund Center for the Study of Securities Markets at Pace University and observe the creative process shaping people and events in financial markets. There are new and exciting challenges facing the industry today -- new conflicts of interest between research and investment banking, new "creative accounting" challenges, and new competitive forces. The process of "creative destruction" remains powerfully at work. Perhaps some student starting out today will benefit from these observations. Good economics has a way of driving out bad policies. Competition tends to win out in the end. Ethical dilemmas are almost inevitable in business and those playing the game should be prepared to face them squarely. Training in economics can be immensely helpful in an economy where "creative competition" remains a powerful force. A sense of humor can be a means of survival. And whatever its blemishes, this country remains a land of great opportunities for those willing to seize them. 6