Technology on Campus: An Ethnography of College Life

advertisement

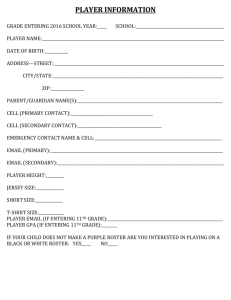

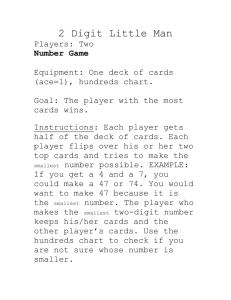

1 Technology on Campus: An Ethnography of College Life Someone once told me that to write well you have to write what you know. This is what I know. -- Never Been Kissed Introduction During my spring break, I lived with a group of four male students at a major public university in Georgia. My purpose was to gain an insider’s perspective on today’s student life. For five days, I became one of them by sharing the ordinary activities of their lives. In some respects, this was a familiar role for me, since I resumed my own college studies a year earlier. My first college experience in the late sixties, and my recent return to campus for a new and improved education, naturally invited comparisons. Of course, many aspects of college life have not changed. Music and parties still dominate the social scene. ‘Hanging out’ and ‘hooking up’ are new words for age-old pursuits. And students still take to the streets to protest against impending war. But despite similarities, there is one striking difference—today’s student is a digital whiz. The computer is the portal through which students do almost everything. It is a stereo for students who listen to MP3 files and radio Webcasts. It provides quick communication through e-mail and instant messages. It even can substitute for television and an alarm clock. Using the Internet, students register 2 for classes, turn in assignments, browse the library catalog, listen to music, talk to friends, read the news, write papers, and play games (Guernsey, 2000). With this in mind, and my notebook in hand, I set out to develop an in-depth portrait of the effect of technology on college life. Background and Recent Studies Most colleges provide students with the ability to access the World Wide Web, e-mail, and related Internet activities. The Pew Internet and American Life Project recently conducted a quantitative study to examine how college students’ use of the Internet affected their social and academic lives. The Internet Goes to College is a comprehensive statistical analysis of internet use among college students. The study concludes that 86% of college students go online compared with 59% of the general population. While 42% of college students say they use the Internet primarily to communicate socially, nearly as many (38%) use it primarily to engage in work for class. This study included an ethnographic component by using a team of graduate researchers to observe and record the behavior of college students using the Internet in public places (Jones, 2002). The negative effects of widespread computer use also have been studied. College students may be particularly susceptible to problems related to excessive Internet use. One recent study of a college population identified a small group of students who use the Internet to a degree that interferes with other aspects of their lives. Compared to an average of 100 minutes per day for all respondents, roughly 6% of the sample group reported more than 400 minutes 3 per day online. Most of these were male students in the hard science academic majors (Anderson, 2001). My reading and initial observation suggested that the college experience not only is about classroom learning; it also is about developing new social skills. Quantitative research supported the notion that widespread Internet use was creating a new breed of college students that used the Internet to enhance their social lives nearly as much as to supplement their formal education (Jones, 2002). Other studies suggested that increasing dependence on the Internet had the potential to interfere with the important social interaction and emotional development associated with college life by reducing everyday activities, interfering with real-life interpersonal relationships, and interrupting sleep patterns (Anderson, 2001). My focus was to learn how college students use the Internet and other current technology and to understand the extent to which they experience problems from widespread use. Methodology To conduct my research I observed four male students living in an offcampus apartment at the University of Georgia. My son, who is one of the four, was instrumental in negotiating my entry into a life style generally considered ‘offlimits’ to parents. He and his roommates agreed to let me enter their domain for the purposes of participation and observation. Familiar with the academic demands of college, they were enthusiastic about my fieldwork. Over the course of three weeks, I observed, and to the extent possible, participated in, their daily (and nightly) lives for a total of 40 hours. During my fieldwork, we shared living 4 quarters, meals, ordinary activities and important social behaviors. At the outset, I observed that a tape recorder inhibited open communication, so I opted to jot a few notes during the activities, and follow each session with comprehensive written fieldnotes. A short survey, designed and administered in the field, provided baseline data concerning the range and applications of technology used by my informants. The Appendix contains the compiled results of the survey. As a follow up to my original fieldwork, I conducted informal interviews with key informants. While my status as a parent presented an obvious bias, my status as a student provided a valuable vehicle for establishing rapport with the primary informants and their friends. In group situations, I made a conscious effort to identify myself, explain my purpose, and initiate conversation centered on college issues. Initially this may have presented some confusion or hesitancy as informants tried to understand my role—they had no previous experience with a mother-turned-student and they were curious about my participation in their social rituals, but gradually they accepted my presence and began to offer their insights freely. Discoveries Internet use is a staple of most college students’ educational experience. For the majority of students, the Internet is a functional tool that has greatly altered the way they interact with others as they go about their studies. My informants reported most academic courses have an online component, commonly in the form of a Web-based syllabus and instructional materials or 5 interactive assessments. Bobby and Brian regularly participate in virtual study groups that allow them to meet and discuss assignments with other classmates who live off campus. Bobby attributes his improved academic performance to increased use of Internet technology, especially for research. Even Jared, who ‘hates computers’, uses the Internet to access library materials. Electronic mail allows him to turn in assignments, communicate with professors, and keep up with course requirements. College students’ social experiences account for a great deal of their learning outside the classroom. It was not surprising to find that my informants use the Internet more as a means of social communication than for educational purposes. Three of the four boys use instant messaging (IM) while all four use e-mail to stay in touch with friends and family. At my initial interview with John, I was able to contact him with a text message from my cell phone that appeared on his computer screen as an IM. The advent of wireless Internet service on campus may raise important new issues of etiquette and privacy for home and classroom. Internet technology also provides a meaningful leisure activity in the form of interactive gaming. Like a techno version of playing cards or shooting pool, gaming is more of an extracurricular activity with a new twist—participants compete online these days. younger brother back home. Bobby has a weekly match scheduled with his Brian and John offer to demonstrate with an impromptu game called Unreal Tournament, and call Brad—apparently the best player—to join them. The object of the game, they tell me, is to kill the bad guys 6 John at ‘command central’—his computer before they kill you. While they play, they shout back and forth from one room to the other about the game. Brian’s face comes to life as he describes the features of his new (third) computer, which is no larger than a car battery. He is building this small computer to use at LAN parties, where players get together in one room and hook up their computers to the local area network. Despite the fierce competition and wild enthusiasm, this activity is more about hanging out with friends than it is about the game. Video games often replace television time. On the rare occasion I observed informants watching television, it was to view a sports event or favorite program. Napster may be gone, but file sharing is still huge (Brown, 2002). At my first meeting with Jared, he showed me his tiny MP3 player, which measures one inch by two inches. He downloads tons of music from sites like Kazaa. John 7 also downloads music and uses his computer to create re-mixes for his work as a deejay. Tiny tunes—Jared downloads tons of music for his MP3 player The Internet is not the only means of communication for college students, and in some cases, is not the preferred choice. The widespread use of cell phones makes this a popular choice for social communication—what Bobby dubbed his ‘life line’. The cell phone allows Jared the comfort of checking in with his mother from a room full of people and Brian the convenience of sending a text message from class to remind John of dinner preparations. In the oftencrowded downtown Athens club scene, the cell phone is sometimes the only way to stay connected—even in the same room. Although the Internet has allowed students to communicate in many new ways, it can also lead to more isolation if students choose to interact on-line more than in person. Brian’s roommates teased him about the time he spends at one 8 site where he ‘meets’ girls. While Brian insists this site is not a dating service— the point is to rate each girl based on photos and biographical sketches—the time spent in the virtual world is not real social interaction and is a poor substitute for making new friends. The presence of the computer can also sway some students away from academics (Guernsey, 2000). Although no one would comment directly, there were suggestions that John’s poor academic performance may be partly due to the long hours he spends online. Finding the right balance seems to be more difficult for some students. Both John and Brian reported that the tendency to log on to the Internet late at night ‘sometimes’ interfered with their sleep patterns and made it difficult to wake up for morning classes. Conclusion Today’s college student will be well prepared to live and work in a wired world. When I started this research project, I was expecting to find that college students were allowing Internet technology to replace important social relationships. I was surprised to arrive at the conclusion that the Internet serves to facilitate rather than replace social interaction. Enhanced communication, through the Internet and cell phones, allows students to maintain close relationships with parents and distant friends and permits a greater range of interpersonal contact than past generations of college students experienced. I underestimated the amount of time required to build trusting relationships with my informants, perhaps due to the generation gap. At the end of the week, when I had finally achieved the comfort level and openness I wanted, it was time to 9 return to Atlanta. I would have loved more time to explore the issue of privacy that was raised by my informants. After my original project was complete, I realized I needed more information and made time to interview three of the four informants before this revision. 10 Appendix Page Student Technology Survey 11 References 12 Works Consulted 13 11 Student Technology Survey Results Compiled Based on a sample of 4 students Please list the technological devices that you have in your own room. Computer (5) PDA (3) Cell Phone (4) MP3 Player (1) DVD Player (2) Playstation 2 (1) CD Player (1) What type of internet connection do you have? Is this satisfactory? Cable Internet connection is installed (4) Prefer Ethernet (1) Prefer DSL (2) How much leisure (non-academic) time do you spend on the internet per day? 5-6 hours (1) 3 hours (1) 4-5 hours (1) 30 minutes (1) For what purposes do you use the computer? E-mail (4) IM/ICQ (3) Filesharing (4) Chat rooms (2) Movies (3) Music (4) Web browsing (4) Single Player Video Games (4) - Dungeon Siege, Hitman (2), Age of Mythology (3), Red Alert LAN Gaming (3)- Unreal Tournament (2), Age of Mythology (2), Black Hawk Down (2) How does the Internet affect your academic, social, personal life? Academic: online class discussions, quizzes, registration, class correspondence, research papers (3) Social: meet new people, keep up with family and friends (3), girlfriends, discuss programming and security with other members of HAQDAY Personal: affects sleep patterns (2) How do you use your cell phone? Primary phone (4), address book, text messaging (2), web-browsing, e-mail, card games, clock, alarm, ‘it’s my life line’ (1) 12 References Anderson, Keith J. (2001). Internet use among college students: an exploratory study. Journal of American College Health, Vol. 50 Issue 1, pages 21-27. Retrieved March 3, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database. Brown, Eryn & Sonneborn, Scott. (2002). 33 days 8 campuses 127 kids and an infinity of gizmos. Fortune, June 24, Vol. 145 Issue 13, pages 126-134. Retrieved March 3, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database. Guernsey, Lisa. (2000). For the new college B.M.O.C., ‘M’ is for ‘machine’. New York Times, August 10, Vol. 149 Issue 51476, p. G7. Jones, Steve. (2002). The internet goes to college: how students are living in the future with today’s technology. Pew Internet & American Life Project, September 15, 2002. Retrieved March 3, 2003, from http://www.pewtrusts.com/pdf/vf_pew_internet_college.pdf 13 Works Consulted Bishop, Wendy. (1999). Ethnographic writing research: writing it down, writing it up, and reading it. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook. Chiseri-Strater, Elizabeth & Sunstein, Bonnie. (1997). FieldWorking: reading and writing research. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. Kindlon, Dan. (1999). Raising Cain: protecting the emotional life of boys. New York: Ballantine Books. Pollack, William. (1998). Real Boys. New York: Henry Holt. Sanjek, Roger. (1990). Fieldnotes: the makings of anthropology. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. . 14