Appendix B. Sentence Correctness

advertisement

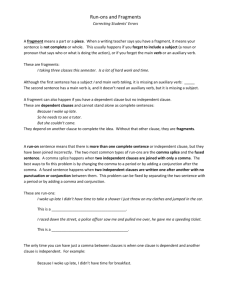

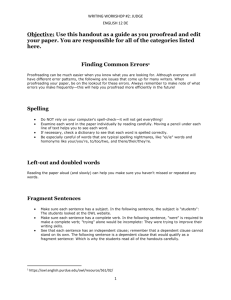

Appendix B. Sentence Correctness. If it helps, think of a composition as a jigsaw puzzle. Usually, when we put together a jigsaw puzzle, we look for two things: shape and context. Each piece we take up is judged by its edges: we want to know where it is likely to fit into the matrix of pieces we’ve already laid down. But it is also judged by what it depicts. Is it part of the sky? A piece of a tree? The edge of a boat’s sail? In other words, each piece of the puzzle has two tasks to fulfill: it has to fit in smoothly with the other pieces, and it has to help complete an overall picture. Sentences are not pieces of a puzzle – not really. For one thing, the pieces in a jigsaw puzzle are given to us in a box, already cut and waiting to be fitted into their proper places. When we compose an essay or any other piece of writing, however, we have to build our own pieces. But sentences, like puzzle pieces, must fit smoothly with what precedes and follows them, and they have to contribute to an overall message. To understand how sentences and parts of sentences fit together, we need to know a few basic facts. Clauses and Phrases. First of all, we need to distinguish between clauses and phrases. A clause is a group of words with a subject and a main verb, like so: “Jim ran as fast as he could.” In this group of words, “Jim” is our subject, and “ran” is our main verb. The rest of the word group, “as fast as he could,” modifies the verb, telling us more about the way “Jim ran.” When a group of words has both a subject and a verb, we call it a clause. When a word or group of words lacks either a subject or a verb, we call it a phrase. There are many kinds of phrases. There are prepositional phrases: “onto the table,” “into the mouth of madness,” “along the edge of a razor,” and “to the corner store,” for instance. There are verb phrases: “swinging wildly at the air,” “playing for all he was worth,” or simply “was walking.” There are noun phrases: “the red Toyota Celica,” “John’s auburn flat-top,” or “the day Janet stopped talking to me.” Note that in the last example, the noun phrase contains its own verb, “stopped.” In fact, look closer and you’ll see that it contains a whole clause: “Janet stopped talking to me.” But – and this is very important – the subject of the phrase is clearly “the day,” and since there is no main verb associated with that subject, we cannot call this word group a clause. This is how we determine that we’re dealing with a phrase instead of a clause. A clause must contain both a subject, and a main verb that we can link to that subject. Here’s the point: phrases do not form complete sentences because they do not tell us all we need to know. They supply only part of the information. When we speak, we are accustomed to using phrases in place of sentences, and that’s fine. The context is different in spoken English than in written English. For example, if my wife asks me, “Where are you going?” I can answer her with “To the store” (a prepositional phrase). She is supplying one side of a necessary contextual arrangement. In effect, she’s beginning the thought, and I’m finishing it. But when I write, I have to supply both sides of that contextual arrangement, so I need complete sentences. Different Kinds of Clauses. Be careful, though. Not all clauses are sentences. Some clauses, while they contain both a subject and a main verb, still don’t form complete expressions. For example, look at the following clause and ask yourself what is being expressed: “After David ate the rest of the pie.” The word group has a subject (David) and a main verb (ate), but most of us find ourselves asking, “What happened after David ate the pie?” The thought is incomplete. This is because of that one word, “after,” which we call a subordinating conjunction. Because of this subordinating conjunction, the reader expects more information to follow or precede the clause. We call clauses like this one subordinate clauses or dependent clauses. They do not form complete expressions, so they cannot stand on their own as sentences. Dependent clauses usually begin with subordinating conjunctions such as “after,” “because,” “whereas,” “while,” and so forth. Any standard composition handbook will provide you with a more complete list of these words. Each sentence, to qualify as a complete expression, need a word group which contains both a subject and a main verb, and functions as a complete expression. In other words, every sentence, no matter what else it contains, must contain a clause that can stand on its own. We call these main clauses or independent clauses. Here’s an example: “He ran the mile in just under five minutes.” Compare the following word groups, and see if you can spot the complete sentences. 1. Renee ran faster than she’d ever run in her life. 2. Because Michael didn’t have the money to get into the theater. 3. Our cat’s litter box, which stood in the corner of the upstairs bathroom, next to the shower. 4. What a tangled web we weave. 5. How many licks does it take to get to the center of a Tootsie Pop? 6. Not a single one of the fifteen dancers auditioning for the play. 7. When the age is in, the wit is out. 8. After David ate the rest of the pie, he spent a solid hour in the swimming pool, just floating and moaning. 9. Becky could have paid Michael’s way, but she refused. 10. Renee was the winner because she tried harder than the others. Notice that some of these word groups contain both dependent and independent clauses. That’s okay. We call those kinds of constructions complex sentences. The key is that they do contain an independent clause. Without that, they can’t be sentences. For example, take a look at #2. Here we have a classic dependent clause. We have a subject (Michael) and a main verb (didn’t have), but we have that word “Because” at the beginning, which tells us we’re going to need something else to help this word group become a complete expression. Now look at #9. Here we have two independent clauses joined by a comma and the word “but.” That word is known as a coordinating conjunction, and it is a common way of connecting clauses together. In this case, it connects the independent clause, “Becky could have paid Michael’s way,” with the independent clause, “she refused.” If you don’t think that last word group is an independent clause, look more closely. It has a subject (she) and a main verb (refused), and it forms a complete expression. That’s all it takes to create an independent clause. What about #7? This begins with a dependent clause (When the age is in), and we know this is a dependent clause because it has a subject (age) and a main verb (is), but it also begins with a subordinating conjunction (When). But the next part of the word group, “the wit is out,” is an independent clause. So here we have a complex sentence. Sentence Combining. Independent clauses and dependent clauses can be brought together through a set of possible combinations, some of which require specific punctuation. For simplicity’s sake, let’s refer to independent clauses as ICs and dependent clauses as DCs from here on out. And let’s take a look at how these ICs and DCs can be combined. First, let’s say we want to combine two ICs. Let’s take, for example, the IC “Michael’s cash ran out” and the IC “He was forced to borrow from Becky.” We could combine these ICs by simple coordination. We would do this by introducing a comma and a coordinating conjunction. “Michael’s cash ran out, and he was forced to borrow from Becky.” This is known as a compound sentence, when two ICs are brought together. There are other ways to create compound sentences. One is to use a semicolon, like so: “Michael’s cash ran out; he was forced to borrow from Becky.” Another is to use a semicolon, and to add a conjunctive adverb followed by a comma, like so: “Michael’s cash ran out; therefore, he was forced to borrow from Becky.” Note that in each of these examples, the ICs remain balanced. Each is as important as the other. Now what if we wanted to reflect that one IC was more important, or was the real focus of what we were trying to say? One good way to do this is to use subordination. When we subordinate one IC to another, we turn it into a DC. Let’s take our example of Michael and Becky, and let’s say that the real focus of our message is the borrowing, rather than Michael’s cash-flow situation. To reflect this, we want to turn our first IC into a DC, and to do this, we need to attach a subordinating conjunction. Let’s use the word “because.” Here’s one way to handle this: “Because Michael’s cash ran out, he was forced to borrow from Becky.” Take a closer look at that new word group. The pattern looks like this: Because IC, IC. It’s a complex sentence because it combines an IC with a DC. When we combine an IC and a DC by placing the DC first, we have to set off the DC by following it with a comma. In fact, if you look at the sentence I just wrote, you’ll see it follows the very same pattern: When IC, IC. If we replace “when” and “because” with a code for subordinating conjunction (let’s use sc to avoid confusion), we see another way to look at this pattern: sc IC, IC. But what if we want the DC to come second? Well, we could just reverse the order and get rid of the comma, like so: “He was forced to borrow from Becky because Michael’s cash ran out.” But that’s a bit confusing. It sounds like someone else, a third party, was trying to borrow from Michael, but then had to borrow from Becky. Nah, we don’t want that. So let’s rearrange things a bit. “Michael was forced to borrow from Becky because his cash ran out.” There we go. Complex sentences which place the DC after the IC usually don’t need a comma to separate the two. The exception (there’s always an exception, isn’t there?) is when the DC expresses something contrary to the IC, like this: “Michael said he had run out of cash, though Becky knew he was holding onto a twenty.” Okay, let’s take a look at some of those patterns again. We can combine two ICs to form a compound sentence by using a comma and a coordinating conjunction (let’s call this a cc); by using a semicolon; or by using a semicolon and a conjunctive adverb (we’ll call this a cadv). IC, cc IC. IC; IC. IC; cadv IC. We can combine an IC and a DC to create a complex sentence by placing the DC first and setting it off with a comma, or by placing it second and doing without the comma (except in cases of contrary expressions). DC, IC. IC DC. (or IC, DC. in the case of contrary expressions) Finally, we can combine these elements into a compound-complex sentence by joining two or more ICs with one or more DCs using any or all of the methods listed above for compound and complex sentences. Check this out… “When, after a heavy rain, the streets give back the colors of the neon signs, although I cannot claim to be such a lover of the city as to prowl in its darkest shadows with the poets and the paparazzi, I often long to walk the sidewalks, remaining always in the light of the street lamps, and taking in the smells of the newly-washed concrete, so I set out from my door, collar up, shoulders hunched, and seek out the places where darkness and danger are things nearly touched but never quite tasted.” Believe it or not, that’s a correct sentence, and while it might not be something most of us would feel comfortable writing, it has a style of its own. It even tells us something about the personality of the writer (or speaker). Let’s take it apart and see what makes it tick, shall we? First of all, we begin with the word “when,” which we know is a subordinating conjunction. In fact, if we overlook the prepositional phrase (“after a heavy rain”) tucked into the first word group, we can recognize a DC: “When…the streets give back the colors of the neon signs.” It has a subject (streets) and a main verb (give), but it doesn’t form a complete expression. The prepositional phrase doesn’t keep this from becoming a DC; it just adds a little more information by telling us when the streets are giving back the colors of the neon signs. So we’re starting with a DC, set off by a comma, like so: DC, Now let’s take the next word group, and for the sake of simplicity, we’ll try to stick to clauses. So we end up with “although I cannot claim to be such a lover of the city as to prowl in its darkest shadows with the poets and the paparazzi,” This is another DC, set off at the end by another comma. It has a subject (I) and a main verb (claim), and it begins with a subordinating conjunction (although). So we’re looking at this, so far… DC, DC, The third word group is “I often long to walk the sidewalks, remaining always in the light of the street lamps, and taking in the smells of the newly-washed concrete,”. This is a pretty standard IC, followed by two modifiers using an –ing verb to add more information about what our narrator does when he walks. The basic sentence is “I long to walk the sidewalks,” right? So, again leaving aside the modifiers and so forth, we can plug this IC into our chart for this sentence so far, and we get this: DC, DC, IC, Right after that IC, we have another IC: “so I set out from my door, collar up, shoulders hunched, and seek out the places where darkness and danger are things nearly touched but never quite tasted.” Believe it or not, the core of this whole sentence is just this: “I set out…and seek out the places.” The rest is a coordinating conjunction (so), some modifying phrases (collar up, shoulders hunched), and a relative clause (where…tasted) that serves to modify “places.” For all its complex appearance, this last word group is just an IC connected to the previous IC with a comma and a coordinating conjunction. That means our final chart for this sentence looks like this: DC, DC, IC, cc IC. If we look at our rules for sentence combining, we can see that this is all correct. A DC which comes at the beginning of a sentence should be set off with a comma. We’ve done that. And we can combine two ICs with a comma and a coordinating conjunction. We’ve done that. It’s a long sentence, that’s for sure, but the important thing is that it is not a run-on.