Title: Nature in Native American Literatures

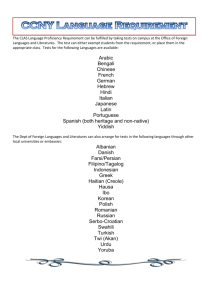

advertisement

Title: Nature in Native American Literatures Author(s): Hertha D. Wong Source: American Nature Writers. Ed. John Elder. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1996. From Scribner Writers Series. Document Type: Topic overview, Critical essay Full Text: COPYRIGHT 1996 Charles Scribner's Sons, COPYRIGHT 2007 Gale, Cengage Learning IN 1969, for the first time, the Pulitzer Prize for literature was awarded to an American Indian writer. N. Scott Momaday 's receipt of the prestigious award for his novel House Made of Dawn (1968) initiated what some scholars have called a Native American Renaissance, a period of renewed interest in and publication of American Indian writers. Whereas Vine Deloria, Jr., has noted that fascination with American Indians seems to ebb and flow in twenty-year cycles, interest in literature by Native American writers has been growing consistently since the 1960s. The importance of place, the narrative dimensions of history, the potency of storytelling, the possibility of (re)connection to cultural traditions, the struggle to define Indian identity, the translation of oral literatures into print, the interconnectedness of all forms of life, the sacredness of the earth, and the insistence on the power of language to articulate and influence are all central aspects of contemporary Native American literatures. Because indigenous people have long been written about (particularly by anthropologists) but less often have written for themselves, because educators are increasingly committed to a broadly multicultural curriculum that reflects the diversity of the United States, and because some of those concerned with the challenges of the postmodern age (such as environmental destruction and spiritual skepticism) seek alternative models to those originating in Western Europe, it seems likely that Native American literatures will continue to grow in appeal. The association between nature and Native American cultures is well known. A wide array of Indians and non-Indians · from environmentalists to spiritualists, from academics to history buffs · routinely invoke a vaguely defined "love of Mother Earth" and a kinship with all living things as defining features of Native American modes of thought. Even though there is great diversity of culture, language, and geography throughout the hundreds of nations in Native North America, a sense of intimate connection to the land is central to most, and such a geocentric perspective is reflected in Native American literatures. What follows is an attempt to sketch in very broad strokes the inclusive conception of nature shared by many indigenous peoples. More particularly, the focus here is on how place · precise geographic locations and the network of relations enacted within them · is important in American Indian literatures. Definitions and Terminology Before considering how the natural world is represented in Native American literatures, it is important to clarify a few terms and ideas used throughout this essay. The term "Native American," for instance, is used interchangeably with "American Indian." Both are used to denote indigenous people, that is, descendants of those culture groups who have lived longest in a particular region. Since many Native Americans refer to themselves simply as "Indians" subverting the European misnomer to make it their own, "Indian" is used occasionally as well. Also, in this discussion, "Native American," "American Indian," or "Indian" refers to persons indigenous to what is now the United States rather than to the Americas generally. Although "indigenous" is associated with an intimate connection to a specific geography, the term applies also to nomadic peoples and to those who have been dispossessed of or removed from their homelands, because people can be linked to a particular place (via tradition, history, memory, or story, for instance) even when physically separated from it. Native American Perceptions of Nature The distinction between Western and non-Western notions of nature has often been noted. Although any generalization has limitations and an element of misrepresentation, it is true to say that, in general, European Americans consider themselves separate from, and often superior to, nature, whereas indigenous people see themselves as part of the interconnective web of the natural world. As a consequence of such culture-specific assumptions, European Americans have seen naure as a potent force to be subdued and as a valuable resource to be used, whereas Native Americans have viewed nature as a powerful force to be respected and as a nurturing Mother to be honored. In contrast to the hierarchical Judeo-Christian tradition, Native American traditions emphasize egalitarianism. Native people, says Laguna Pueblo writer and English professor Paula Gunn Allen , "acknowledge the essential harmony of all things and see all things as being of equal value in the scheme of things" (Studies, p. 5). "Even a rock has spirit or being," explains Leslie Marmon Silko , "although we may not understand it" ("Landscape," p. 84). Nature, then, which includes all celestial bodies, animals, plants, rocks, and minerals, is not separate from humans. Native American cultures and the narratives they generate both arise from and refer to specific geographic sites. Just as European Americans often define themselves in relation to a specific social geography, so Native Americans often define themselves in relation to a precise physical geography that is mapped in a network of social relations (such as kinship and clan relations). A set of binary oppositions (itself a western mode of thought) oversimplifies the issue and might better be replaced by a spectrum of positions that reflect the diversity of perspectives within both groups. Nevertheless, the contrast between European American and Native American perceptions of nature accurately describes some of the basic assumptions that illuminate the dominant behavior of these two sets of cultures. Indians and Environmentalism Although pre-Columbian indigenous people in the Americas lived intimately and respectfully with the plant and animal life of their environments (what we call today an ecological awareness), pre- twentieth-century indigenous people would not have considered themselves "environmentalists." First, the term suggests a separation between humans and the rest of the natural world that many Native people would not have acknowledged. Second, the term is specific to a particular historical period and is used most accurately to reflect a twentieth-century philosophical and political awareness of the interrelatedness of all aspects of nature and the simultaneous fear of global destruction. Historians caution against interpreting the past from the point of view of the present (a practice not entirely avoidable; historians, of necessity, interpret and construct the past from the present moment) because such a strategy ignores the political, economic, and social conditions of a previous period. What we interpret today as indigenous environmentalism did not arise from fear of the human destruction of the natural world but rather from a pragmatic understanding of the reciprocity between humans and all living beings (including, for example, kinship with celestial bodies, land, animals, and plants). And such reciprocity was due, at least in part, to how human survival depended on precise knowledge of the properties of plants, the habits of animals, and the configurations of the geography within which they all existed. Environmentalists have often looked to Native American cultures for models of living in harmony with nature. Sometimes nonIndians have used Indians as images of a people living in an Edenic, pretechnological era; sometimes they have even revised the words of Native speakers to suit their own political agendas. The history of the so-called environmental speech of Chief Seattle (Seeathl), researched by Rudolf Kaiser, is a good example of how Indians have sometimes been reinvented and (re)presented to suit the interests of the dominant society. In this case, Seattle has been presented as a natural ecologist. The ecological speech so popular in the United States and Europe is, in fact, primarily the work of several non-Indians. The fourth version of Seattle's speech, displayed at the 1974 world's fair in Spokane, Washington, is a poetic adaptation of the third. The third version was rewritten substantially in 1970-1971 by scriptwriter Ted Perry. Perry's version, in turn, was inspired by the second version · William Arrowsmith's revision in 1969 of the "original" record of the 1854 speech. But the "original" speech is really a written record of what Dr. Henry A. Smith remembered of Chief Seattle's address several days after having heard it. In short, Perry rewrote Arrowsmith's revision of Smith's remembered reconstruction of Chief Seattle's words. Such an editorial history makes it difficult to know with any certainty precisely what Chief Seattle said. It seems clear, however, that Chief Seattle was reconstructed as an environmental spokesperson in the 1970s. Similarly, some writers, artists, environmentalists, spiritual seekers, and consumers of popular culture have invented the "Indian" in the preferred images of the dominant society, often transforming complex and diverse Native people into a monolithic cultural commodity whose signs (feathers, beads, and ecological orations, for instance) can be exchanged in a market economy. Many non-Natives seek inspiration and vision from indigenous cultures; as a result there have been discussions of if, when, and how such cultural borrowings are appropriate. Given the devastating effects of colonialism on indigenous people, some Native people fear that, not satisfied with Native land, non-Indians now want Native knowledge. Non-Indians' gleaning what they want (and often only superficially understand) from Indian knowledge and culture, they conclude, amounts to cultural theft, an act that participates in cultural genocide. Others, believing that a paradigm shift is necessary for global survival, choose to share their beliefs, traditions, and narratives with anyone genuinely interested. Momaday, for instance, suggests that the Kiowa "regard of and for the natural world" could be used as a model by all Americans who are afflicted with a "kind of psychic dislocation" ("Man," pp. 162, 166). That this is not a simple matter is reflected in the ever-growing legal battles that are part of an attempt to define intellectual (and cultural) property and the ongoing debates to clarify the ethics of representation. Some Native Americans scholars and writers have written in response to western nature writers and historians, critiquing, correcting, and refining terminology and, in the process, expanding culture-bound perspectives. Alfonso Ortiz, an anthropology professor and San Juan Tewa Indian, has critiqued the term "frontier," for instance, because "one culture's frontier may be another culture's backwater or backyard" ("Indian/White Relations," p. 3). Similarly, "wilderness," a term dear to seventeenth-century colonists, nineteenth-century historians, and twentieth-century environmentalists and one associated historically with Indians, reflects a colonist's point of view. In the early days, wilderness and Indians were both depicted by Europeans as "wild." But "Only to the white man was nature a wilderness," says Luther Standing Bear in Land of the Spotted Eagle (1993; 1978 ed., p. 26). The wilderness may have been unknown and frightening for newcomers, but it was home to those who lived there. Now, more often than not in popular culture, wilderness and Indians represent a physical and spiritual retreat, respectively, into a pristine past in which humans and nature lived harmoniously and where a promise for the future may be found. Native American critiques of European American environmentalist terminology should not suggest that Native people are unconcerned about environmental issues, but rather that they are acutely aware that both the destruction and the protection of the earth, air, and water have been dominated by European-American self-interest. Ironically, although they have been made the symbols of environmentalism by some non-Natives, Native Americans often find themselves at odds with environmentalists, particularly when indigenous rights to hunt or fish may be at stake. Although "frontier" and "wilderness" take on entirely new meanings (and histories) when considered from the "other" side of the frontier or from a home situated within the "wilderness," less obviously colonizing terminology is being challenged as well. Silko has suggested a reconsideration of the word "landscape," for instance, because "scape" insists on a perceiver who is separate from, outside the world being viewed. Landscape, then, with its linguistic split between human observer/nature observed cannot convey a "human consciousness [that] remains within the hills, canyons, cliffs, and the plants, clouds and sky" ("Landscape," p. 84). Similarly, in Place and Vision, literary scholar Robert M. Nelson criticizes the term "sense of place" because it "privileges the process of human identification" and, in so doing, diminishes the importance of nature as it is. These terms imply that the natural world has value "only as it enhances and serves our human lives" (p. 8) rather than affirming, as Chickasaw writer Linda Hogan thinks they should, that all parts of the natural world are "invaluable not just to us, but in themselves" ("What," p. 16). Such interrogations of the very categories and perspectives imposed by language make it clear that language is not a neutral medium for, but rather a partisan constructer of, the world · and, more significantly, that the recovery and maintenance of Native languages are important contributions to reenvisioning human relationships with the rest of the natural world. In fact, the written versions of Native American oral literatures recorded by non-Indians are the result of multiple translations: from speech to print, often from a Native language to English, from performance to page, and from one cultural community to another. The resulting ethnographic document is always a translation, a version of a single (or several) performance(s) from a specific historical moment in a precise place shaped by a singular audience and reconfigured by a (usually) European American amanuensiseditor. Rather than being viewed as static, "authentic" sources, written translations of myths, songs, and stories are better considered recorded versions of continuing but everadaptive practices of oral narration. Brief Overview of Native American Literatures Three basic categories of Native American literatures have been outlined: (1) oral literatures, including myth, ritual dramas (such as ceremonies, songs, and rituals), narratives (myths, tales, and histories, for instance), and oratory; (2) life histories that were often recorded and translated by a non-Native amanuensis-editor; and (3) written literatures that (leaving aside picture writing) began in the eighteenth century. These three categories suggest the historical span and the formal diversity of Native American literatures. Oral literatures, with roots in pre-Columbian times, continue to be told and performed today. Like life histories, many were recorded, translated, and edited by European (American) historians, ethnographers, government and military officials, clergy, journalists, and others. Although accounts of indigenous life have been produced since first contact, intensive and systematic recording of oral literatures and personal narratives began in the late nineteenth century and continues, to some degree, in the late twentieth. Many oral narratives, performed and interpreted in their own cultural and historical contexts, were meant to be heard and seen collectively rather than read individually. The written texts, then, are translations or "retranslations" of oral performances. Some scholars believe that in such collaborative texts any Native American voice is erased or suppressed; only the voice of the editor, usually a member of a colonial power, remains. Others insist that these cross-cultural texts constitute a third space that both distinguishes and connects cultural and literary boundaries, allowing readers to apprehend both the voice of a Native American speaker and the pen of a European American editor. Literary scholars have theorized about such collaborations as the "textual equivalent[s] of the frontier" (Arnold Krupat), "literary boundary cultures" (Hertha Wong), or "contact zones" (Mary Louise Pratt) · all ways to talk about a bicultural site of literary and cultural interaction. Today both written literatures (such as poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and drama) and oral literatures (such as stories, songs, and spoken life histories) are thriving. Although most Native American writers-performers write or speak in English, others, like Rex Lee, write in Native languages or, like Luci Tapahonso and Ray A. Young Bear, compose bilingual texts. Oral literatures continue to be performed in many Native communities, both reservation and urban. Nature in Oral Literatures Of the many forms of oral literature, origin myths reveal most clearly a people's orientation to the land. Among Native North American origin myths, three basic types, each delineating a specific relationship with the natural world, have been outlined. Earth Diver myths, Emergence myths, and Earth Created myths. Many times, these creation myths are followed by migration narratives in which the people locate and/or create their physical and cultural home. In all three myth types, a portion of creation often exists prior to the creation of humans; then humans and animals cocreate or shape the rest of the world. The active engagement in a series of creative acts and the collaborative efforts of human-people and animal-people foster a sense of responsibility and reciprocity, a sense of everything as interrelated and sacred. With their nonhuman colleagues, humans take responsibility for shaping the earth and interacting respectfully with all living beings. In Earth Diver myths (common in the Northeast), for instance, a spirit being (often Sky Woman) descends from the sky to a watercovered earth. Animals volunteer to dive deep to the bottom of the water to retrieve some soil upon which Sky Woman may rest. Often after four attempts involving great effort and sacrifice, a tiny morsel of soil is brought up. (In many indigenous cultures, four is a sacred number associated with the four cardinal directions, the four elements, the four ages of human beings, the four seasons, and so on.) In the Northeast, Turtle offers her strong, round back as the support for the soil, the reason earth is often referred to as Turtle Island. In Emergence myths (common in the Southwest), prehumans move up within the earth, changing form and consciousness as they move from one world to another, until they emerge into this world, the Fifth World for many cultures. The Kiowa are said to have emerged into this world through a hollow log. The Navajo describe a series of emergences. They began in the First World as insectlike Air-Spirit People, then moved successively into the Second World of Swallow People, the Third World of Yellow Grasshopper People, and the Fourth World of People Who Live in Upright Houses. In the Fourth World, First Man and First Woman were created simultaneously from two ears of corn, the people learned agriculture, and they resolved to do "nothing unintelligent" that would create disorder. Finally, they emerged into the Fifth World of Earth-Surface People in which we live today. Emergence can be understood in psychological as well as physical terms; over time, humans transform from one state of being into another until they emerge into their current cultural identity. In some cultures, male spiritual leaders meet in a kiva, a subterranean ceremonial room sometimes described as representing the womb of Mother Earth. Descending into a kiva is a symbolic return to their origins. Each time the participants emerge from the kiva, they reenact the Emergence, thus reminding the gathered community of their connection to the earth and their shared origins. In addition to Earth Diver and Emergence origin narratives, some creation myths describe how human beings are created from the clay on earth's surface. In one version from the northern Plains, Trickster experiments with constructing humans from clay and baking them. He proceeds by trial and error until he has baked humans in various hues. Similarly, the red pipestone deposits of what is now southwestern Minnesota are sometimes described as the congealed blood of the ancestors · a link to familial and cultural history through a specific site and a particular collection of narratives associated with it. Finally, some creation cycles combine more than one type of origin narrative. According to Young Bear, before the "Mesquakie or Red Earth People . . . were sculpted from the earth," O ki ma, a "human being who came from the very flesh and blood of Creator's heart" was brought into being to guide the people through creation (p. 95). Like O ki ma, Earthdiver (Muskrat) contributed to the beginnings of the earth. Whether humans emerge from, dive for, or are created from it, Earth is at the center of indigenous selfdefinition. Thinking of origin myths may help explain why Allen says that for a Native person to say "I am the earth" is not a metaphor. Native American myths are enacted in ceremonies, and both myth and its ritual reenactment in ceremony articulate an orientation to the natural world. As noted earlier, Native Americans often see themselves in relation to, not separate from, the earth, its creatures, and its cycles; they envision reciprocity (between and among living beings) rather than hierarchy (in which humans have dominion over animal and plant life). But these are ideals, not always realities; thus, ceremonies are necessary to restore harmony, the natural and desired state. Ceremonies, then, are a means to reconnect to self, community, nature, and the cosmos. The patterns and symbolism of ceremonies are not arbitrary. Rather, they arise from a specific landscape. Throughout the arid Southwest, for instance, water is central to most ceremonies. The parallelisms and variable repetitions of songs may be arranged into desirable meteorological patterns, particularly those that bring rain, thus ensuring crops and the continued well-being of the people. Even when the ceremony is performed to heal an individual, because one person is intimately interconnected to everything, it is understood that the ceremony will restore balance to the community and the entire natural world as well. For example, in the Night Chant, a nine-day Navajo healing ceremony, the singer calls forth "dark clouds," "abundant showers," male rain, female rain, and the fecund results of rain, such as "abundant vegetation," "abundant pollen," "abundant dew" · all central to survival in a dry land (Bierhorst, p. 295). By the end of the ceremony, described by John Bierhorst, through the power of ritual language and action, hozho · harmony, beauty, order · has been restored for individual, community, and cosmos. Oral traditions reflect how an intimate relationship with the natural world is central to a Native American sense of identity. Equally important is how oral literatures (ceremonies and narratives) teach each generation how to restore and maintain balance · how, as Abenaki writer and storyteller Joseph Bruchac says in "The Circle Is the Way to See," to "recognize our place as part of the circle of Creation, not above it" (p. 263). Written Literatures A sense of place continues to be a fundamental theme in literature written by Native Americans in the twentieth century. On the one hand, the land is associated with home (often homeland) and tradition; on the other hand, land is a reminder of the loss of land, life, and culture under colonialism. More often than not, when protagonists of Native American novels return to their homelands, the homecoming is a means to find their Indian identities, to reconnect to their histories and cultures. "The story of my people and the story of this place are one single story," a Taos Pueblo man is reported to have said (Ortiz, "Indian / White Relations," p. 11). For Native writers, said Bruchac in a lecture, autobiography and nature writing are basically the same thing, because "you can't tell your story without telling the story of the earth." He cites the example of studies of Native American kindergarten children who drew pictures in which they were depicted as tiny figures in a vast natural setting that included animals and plants. The fact that non-Indian psychologists interpreted the children's drawings as indicative of "low selfesteem" suggests the wide gap between European American and Native American notions of nature. A Native interpretation, according to Bruchac, is that the children show a healthy sense of themselves as part of, not dominant over, the natural world. This may be one reason so many of those who related their life stories to European American amanuenses in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries refused to speak of their experiences after removal onto reservations. How could they tell their life stories when they were removed from the land that animated their entire histories and cultures? According to many Native American writers past and present, the land itself is storied. Hunting stories may have been entertaining, but they also educated listeners about animal migration paths, water holes, and geographic landmarks. As Silko explains in her essay "Landscape, History, and the Pueblo Imagination," such tales mapped a terrain and the relationships upon and within it. These stories literally assisted survival. A landmark noted in the narrative might serve as a map to help the listener to find his or her way home. Perhaps more important, stories of place contain the entire history of a nation. When a narrative about the origin of a specific mountain or rock formation is told, the people are connected to a land, a culture, and a history. Just as stories educate the people about geography, history, and culture, so a specific geographic site recalls these tales to the people. Ortiz tells a story about the time he took a trip to southwestern Colorado with a fellow Tewa Pueblo Indian who had never been in that part of the country. At a certain point, his friend began to recognize the terrain from the stories he had heard all his life from the elders. He repeated "tale after tale of events in the early life of our people" that had taken place in that area. We "began to realize," says Ortiz, "that we were retracing a portion of the ancient journey of our people." Finally, the distinction between present and past was blurred as the two men thought of their ancestors who had made similar pilgrimages. "He had heretofore never journeyed here," explains Ortiz, "but now it was as if he had come home" (Beck and Walters, The Sacred, p. 78; Ortiz, "Look to the Mountaintop," pp. 89-90). Place, animated by story, links past and present, departed ancestors and the living. Whereas Ortiz links the land to San Juan Pueblo history, Silko relates the land to Laguna Pueblo mythology. She tells the story of a "giant sandstone boulder about a mile north of Old Laguna," a place that always evokes the "story about Kochininako, Yellow Woman, and the Estrucuyo, a monstrous giant who nearly ate her" ("Landscape," p. 89). The Twin Hero Brothers killed the giant, cut his heart out, and threw it as far as possible. The "monster's heart landed there," explains Silko, as if she is pointing it out to us, "where the sandstone boulder rests now" (p. 89). Of course, she admits, the boulder may have excited the people to compose an etiological tale, but that does not account for why that particular boulder has a story and many others do not. It is not possible to determine which came first, the story or the land. Finally, Silko concludes that unlike European Americans, for Pueblo people, place (not time) is central to narrative. Allen's essay "The Autobiography of a Confluence" illustrates both Ortiz's sense of the narrative mappings of the earth and Silko's insistence on the centrality of place in narrative. The land, the people, and the history are linked by spatial networks · particularly highways · and by temporal networks · the stories, not official metanarratives but rather human-interest stories, what some might refer to as gossip, stories that link over time and space. Allen literally maps her past, present, and future, all linked by three central themes: the land, the family, and the road. She describes the Southwest (where she grew up on the Cubero Land Grant, in New Mexico) as the "confluence of cultures." Allen's New Mexico is not simply the tricultural state (Natives, Chicanos, and Anglos), as it has been called in travel brochures, but a mixture of "Pueblo, Navajo and Apache, Chicano, Spanish, Spanish-American, Mexican-American . . . Anglo," including "Lebanese and Lebanese-American, German-Jewish, Italian-Catholic, GermanLutheran, Scotch-Irish-American Presbyterian, halfbreed (that is, people raised white-and-Indian), and Irish-Catholic" (Swann and Krupat, I Tell You Now, p. 145). Situating herself at the house in which she grew up, Allen's persona scans the horizon, noting the mountain to the north, the hills to the east, and the paved road to the south. She follows the road, which traces the contours of the land · in this case, along the arroyo · until it parts from the arroyo; then she traces how the arroyo joins the "San Jose River [that] eventually meets the Rio Puerco, which, in its turn, joins the Rio Grande" on its way south to Mexico and the Gulf (p. 146). Returning to the road, she follows it from Albuquerque east through Tijeras Canyon, stopping to point to Texas, Oklahoma, the Plains and the East beyond. In the next section, Allen sets out on the road again, guiding the reader along "Old Highway 66," noting landmarks: If you go right on the old highway out of Cubero, from the cattle guard southwest of the village, you will pass King Cafe and Bar, where the wife shot the husband a few years ago and got out on $10,000 bail; next comes Budville, once owned by the infamous Bud, who was shot in a robbery. The main robber murderer later married Bud's widow. They were living happily ever after, the last I heard, and it served old Bud right. Or so most people around there believed. (p. 148) She points out the Dixie Tavern, the Villa (which includes a café, motel, and general store), Bibo's, and many other places. These are not historical or geographical landmarks but places where people gather, just off the highway, for rest and replenishment. What is particularly striking is that these places are inhabited by people and stories, past and present. Allen's detailed descriptions of the land are interspersed with those of the landmarks. Occasionally, she will stop at the top of a hill, for instance, and describe the vista. All are connected, not only by the road but also by the stories of those who lived there in the past and live there in the present. In this section Allen also turns west, describing key towns and cities · Grants, Milan, Gallup. Then, just as she invokes the monolithic East at the conclusion of the last section, she describes the West represented by California, a place where edges and extremes converge. By the end of the essay, having mapped her physical, cultural, and spiritual geography, Allen describes herself as living in the "confluence" · the space between West and East, the coming together of many cultures. The Road "has many dimensions," she says; "it exists on many planes; and on every plane it leads to the wilderness, the mountain, as on every plane it leads to the city, to the village, and to the place beneath where lyatiku waits, where the four rivers meet, where I am going, where I am from" (p. 154). Here she provides an image of overlapping communities, notes her ability to reside in or traverse those communities (unlike others, who feel stuck between them), links past and future with the autobiographical present, reconciles opposites, and illustrates that the first-person construction is always plural · connected to people and place. Although an intimate connection to a particular place is crucial for Native American identity, historical dispossession and removal make it not always possible for Native people to know a sense of place by living in their homelands. In fact, the metanarrative of American history · that Europeans marched across the continent, naming and claiming the land of American Indians as part of the grand scheme of Manifest Destiny · relies on the idea of a conveniently "vanishing" (because "savage") Indian. For those many American Indians who live in urban settings or who have no established homelands to which to return, a memory of place often suffices. Rather than a specific homeland, such writers may, as Rayna Green suggests for Native women writers, present the Road · a place that suggests continually being on the way · as home. That may be why memory is a central theme of contemporary poetry and prose by Native American writers. An identification with the land, then, is based not only on where one resides but also on an orientation to that land or to the memory or history of that place. William Bevis offers one of the most insightful and comprehensive considerations of the depiction of nature in Native American writing. "Native American nature," he concludes, "is urban." That is to say, the "woods, birds, animals, and humans are all ‘downtown,’ meaning at the center of action and power, in complex and unpredictable relationships" ("Native American Novels," p. 601). Ultimately, nature is home. It is not surprising, then, that as Bevis notes, in Native American novels the protagonists are all returning home (or at least trying to do so), whereas in European American novels (by men), they are leaving home, lighting out for the territory, in search of new frontiers. In her forthcoming essay, "Recollections," Inés Hernández-Avila situates this discussion in feminist terms when she explains that for many Native American female writers and activists, the "concern with ‘home’ involves a concern for homeland." When colonizers displaced indigenous people, they disrupted Native homes so that the "domestic sphere of home" necessarily became the public sphere. Forcible relocations resulted in leaving not only a homeland but also a home language. Hernández-Avila argues that "this relocation home," both physical and linguistic, can be a "site of contestation and reconciliation." Many scholars have commented on the optimism of contemporary Native American novels, how writers suggest the potential for reconciliation, the possibility of reconnecting to a past that was violently wrenched from Native control and to indigenous religions and cultures that were suppressed or outlawed. Whereas modern and postmodern novels by European American writers generally emphasize fragmentation, alienation, and emptiness that remain perpetually unresolved, many Native American novels suggest, even if only faintly, the possibility of renewal and reconnection. Usually this transformation occurs through a return to one's homeland and ancestral culture. Momaday's novel House Made of Dawn, patterned in part after the Navajo Night Chant, tells the story of a returning World War II veteran. The novel begins with Abel's return to Walatowa, the ancient name of Jemez Pueblo in New Mexico. In his drunken state, Abel does not recognize his grandfather, one sign of his spiritual blindness. Furthermore, he is inarticulate, lacking a voice to define or even acknowledge his own existence. After killing a man and serving time in prison, Abel returns again to Walatowa, where, after his grandfather's death, he joins the ceremonial runners, thereby hinting at the beginning of his healing, that is, his eventual reintegration into the community. By the end of the novel, he begins to see the land (and himself) more clearly, and he finds at least a faint voice in ceremonial song. Like House Made of Dawn, Silko's novel Ceremony (1977) centers on the experiences of a World War II veteran, a mixed-blood Pueblo Indian, who returns to his reservation. Tayo begins the novel as white smoke, invisible and voiceless. His illness is due not only to war fatigue but also to his separation from self, community, and earth, which began before the war. His mixedblood status and his family's shame at his mother's off-reservation life colored by too much alcohol and too many men are symptomatic of a much more expansive illness: a disconnection of cosmic proportions. Throughout the novel, Tayo's story is connected to Laguna Pueblo myth, and both are connected to the earth. Silko tells a multilayered story on two levels: the mythic in poetry form and the contemporary narrative of Tayo in prose. Just as his illness is reflected in the drought, so Tayo's healing parallels the healing of the earth. It takes a collective effort to help Tayo. The old-time medicine man, Ku'oosh, is unable to assist him. Although he is trained in traditional healing, he was never prepared to cure a warrior who is not even sure he killed someone. New diseases need new medicine, so Ku'oosh refers Tayo to the mixed-blood Navajo healer Betonie, who lives in a hogan crammed with calendars and phone books in the foothills overlooking Gallup. Betonie begins the ceremony that Tayo, with the help of many · particularly Night Swan and Ts'eh · must complete. Ts'eh, an embodiment of Yellow Woman, or a spirit being from the northern mountains, teaches Tayo about medicinal plants and caring for the earth and other people. Their lovemaking is described in images of earth, as if his union with Ts'eh is a reunion with Mother Earth (from whom the people have become disconnected, as reflected in the drought). Tayo's journey parallels the mythic journey to restore balance to the earth. Personal, community, and cosmic healing are related and impossible to bring about in isolation. In all his work Momaday invokes the power of place and the memories it inspires. For Momaday, as for Silko, the "events of one's life, take place, take place" (The Names, p. 142). That is to say, life experiences are rooted in the earth. Although he was born in Oklahoma, he grew up at Jemez Pueblo in New Mexico. "I existed in that landscape, and then my existence was indivisible with it" (The Names, p. 142), he explains. In The Way to Rainy Mountain (1969), using three narrative modes, Momaday recalls several journeys: mythic, historical, and personal. He begins by recalling the Kiowa emergence myth. Then he retraces the Kiowa migration from the Yellowstone into the southern Plains, to his grandmother Aho's house in what is now Oklahoma. In addition, Momaday explains the origin of Devils Tower and the Big Dipper. One day, he says, a little boy and his seven sisters were out playing. As the boy chased his sisters, he was pretending to be a bear, and as his sisters ran, they pretended to be afraid. But soon the boy metamorphosed into a real bear, and the girls' pretend fear turned to genuine terror. To escape the claws of their brotherturned-bear, the girls jumped onto a tree stump. When the bearbrother got too close, the stump grew tall, elevating the sisters to safety. The brother reached up to grasp his sisters, scoring the tree with his huge claws. The miraculously tall tree stump, its circumference scored all around by the bear's scratches, turned into Devils Tower, and the seven sisters, elevated into the sky, became the seven stars of the Big Dipper. "From that moment, and so long as the legend lives," writes Momaday, "the Kiowa have kinsmen in the night sky" (Way, p. 8). The tale links the Kiowa to both terrestrial and celestial relations, just as the emergence and migration narratives do. In the process of retelling these stories, Momaday links himself to the land as well as to Kiowa history and culture. Momaday continues his emphasis on the shaping influence of the land in his autobiography, The Names: A Memoir (1976), published seven years after The Way to Rainy Mountain. He describes his visit to Tsoai, better known today as Devils Tower · the monolith dominating the plains of northeastern Wyoming. By contact with that place and the stories it embodies, he is linked to his Kiowa ancestors. As he did in The Way to Rainy Mountain, Momaday begins with the Kiowa origin myth. This time, though, in the epilogue he describes his imaginative journey back to his source, stopping along the way at Devils Tower, finally arriving at his destination: the "hollow log there in the thin crust of the ice" (The Names, p. 167). If The Way to Rainy Mountain is the story of Momaday's journey of return to his grandmother's house, to Oklahoma, and to Kiowa history, here Momaday tells the story of his return to the site of Kiowa origin, a place both geographic and imagined that links the writer to a mythic, historical, and cultural past reimagined in the present. A specific place, like Devils Tower, may initiate personal memories, but, more important, as Charles Woodward notes, such a place embodies and evokes profound cultural memories (Ancestral Voice, p. 211). Louise Erdrich , a Turtle Mountain Ojibwa · German American writer, is best known for her set of novels: Love Medicine (1984; enl. ed., 1993), The Beet Queen (1986), Tracks (1988), and The Bingo Palace (1994). In her tetralogy, referred to by some scholars as a family saga reminiscent of William Faulkner , land is most often discussed in terms of its historic loss. Together the novels tell the multivoiced story of several generations of Ojibwa and German American relatives and community members in North Dakota. Through a variety of narrative voices, Love Medicine describes the life of several Ojibwa families on and near a North Dakota reservation from 1934 to 1984. In The Beet Queen, Erdrich presents a series of parallel stories taking place from 1932 to 1972. The focus is on German American characters (with a few mixedblood characters) in the small town of Argus, North Dakota. Tracks, narrated by only two voices · Nanapush and Pauline · relates the history of a few Ojibwa family members from the great influenza epidemic of 1912 to the federal government's granting of citizenship to Indians in 1924. In The Bingo Palace, Erdrich gathers together all the reservation families in the present by focusing on Lipsha Morrissey, who is related by blood or adoption to many of the characters. In all four books the land is central. All the characters are shaped by the flat, wide-open spaces and the dramatic weather of North Dakota. Erdrich's interlocking stories focus on relations with land, community, and family and on the power of these relations · remembered, reimagined, and narrated · to resist cultural loss. The goal, she says, is to "tell the stories of the contemporary survivors while protecting and celebrating the cores of cultures left in the wake of catastrophe" ("Where I Ought to Be," p. 23). As in so many other Native American novels, homecomings are important in Erdrich's novels. If, as she has said, "people and place are inseparable," the desire to return to family and community may be strong, even though it is not always possible. Love Medicine begins with June Kashpaw, a "long-legged Chippewa woman" (p. 1993 ed., p. 1) who ran away from home, leaving behind the reservation, an abusive husband, and a child. Living in anonymous poverty, disconnected from her past, her family, and herself, June seeks comfort with men, hoping each time that this one "could be different" (p. 3). Finally, after the latest in a series of disappointing white lovers in the "oil boomtown, Williston, North Dakota," a somewhat intoxicated June decides to walk home during an early spring snowstorm. "The snow fell deeper that Easter than it had in forty years," the narrator explains, "but June walked over it like water and came home" (p. 7). In the next section, the reader learns that June never reached home; her death in the snowstorm provides the occasion for all the characters to gather together. Henry, Jr., returns home from the war, then commits suicide. Lipsha, on the other hand, leaves briefly to discover who he is. By the end of the novel, like his mother (June) before him, Lipsha travels across the water to return home. Unlike June, he is successful. Lipsha has a second homecoming in The Bingo Palace with far more ambiguous success. Although he does not succeed in business or love, he learns to truly care for another when he bundles an accidentally kidnapped baby into his jacket as he presumably freezes (just as his mother died in the snowstorm long ago, and just as his father followed June's ghost into the blizzard moments before). A few other characters leave and return to the reservation (most notably Albertine, who is going to nursing school in the nearby Twin Cities), suggesting the possibility of moving between the European American and Ojibwa worlds. But even more pervasive than homecomings are leave-takings, in particular, forced removals and relocations. Forced removal from the land results in the breakdown of family, clan, and community relations. InTracks, Fleur loses her land. After allotment, Native people had to pay taxes on their land. When they were unable to pay owing to lack of money or lack of familiarity with a cash economy or for numerous other reasons, the land was taken from them. The pressures of this arrangement take their toll. Fleur gives her land tax to Nector, who is to deliver the payment, but Nector puts Fleur's money toward his own mother's land instead. "Legally," then, Fleur's land can be confiscated. When she refuses to vacate her land so the lumbermen who purchased the site can cut down the trees, the government arranges for her forced removal. In The Bingo Palace, Fleur regains her land by appealing to what the white dispossessor, the Indian agent, knows best: greed. He trades her the deed to her "worthless" deforested land for an expensive, shiny automobile. Fleur retreats to her land to live on the edge of the lake, far from the most populated part of the reservation. But by the end of the novel, it is again one of her own who threatens her land. Lyman Lamartine, reservation entrepreneur, has big plans for a Las Vegas · style bingo palace to be built on the site of Fleur's cabin. Lulu Lamartine, Lyman's free-spirited mother, who in her senior years turns into an activist for Indian rights, has always been suspicious of how Europeans measure everything. "Numbers , time, inches, feet," Lulu reasons, are "just ploys for cutting nature down to size" (Love Medicine, 1993 ed., p. 281). "If we're going to measure land, let's measure right," she concludes. "Every foot and inch you're standing on, even if it's on the top of the highest skyscraper, belongs to the Indians" (pp. 281-282). But such an assessment does not take into consideration the limited economic opportunities for reservation Indians or the results of colonization. Like Erdrich's Tracks, Chickasaw writer Hogan's first novel, Mean Spirit (1990), focuses on Indian-white interactions and the theft of Native land. As one way to illustrate Indian-white perspectives, Hogan presents three viewpoints of a dramatic explosion at a local oil refinery. In the first, a white woman called China learns "that earth had a mind of its own," that the "wills and whims of men were empty desires, were nothing pitted up against the desires of earth" (p. 183). Father Dunne hears the "sound of earth speaking," (p. 186) but assumes it is God's voice. Michael Horse, an Indian man, disagrees: that "wasn't the voice of God," he counters, but the "rage of mother earth" (p. 187). While the two European American characters are being transformed by Native perceptions (at least they begin to think of the earth as having a voice), Horse offers an ironic corrective to the priest's analysis. Not all whites are transformed, like China and the priest, by their interactions with Native people. Based on historical research into the scandalous dealings with the Osage and the Oklahoma land grab, Hogan tells a murderous story of a world in which human life, particularly Indian life, is expendable for the black oil bubbling below the surface of the earth. Even the Hill people, who have tried to live peaceably apart from the white community, have come down from the hills to try to allay the violent changes they sense but do not fully understand. After they make heroic efforts to resist removal from their home and to stay alive, the Graycloud family's home is blown up in the middle of the night. Although the family survives the blast, the fire line moves "like the blood of the wounded earth" and consumes everything. The family disappears into the inferno-lit night with only their memories. Another dramatic exception to the dominant Native American vision of the possibility of healing through reconnecting to Earth and tradition is Silko's novel Almanac of the Dead (1991). It is as if the Destroyers, who in her earlier novel Ceremony were subdued (not destroyed), have been unleashed and rage unchecked throughout the world, creating havoc and ruin on a global scale. A network of crime and violence, rather than ceremony and narrative, links the world. The land is still central, but now the focus is on its degradation and loss. Politicians, real estate dealers, developers, miners, and other international criminals divide land into parcels, an image mirrored in the trade in human body parts carried on by a seedy character named Trigg. The dismemberment and consumption of the earth and of humans are clearly linked. But this is not merely a literary image of postmodern fragmentation and alienation; rather, it is a critique of colonialism's "vampire capitalism." Silko's almost 800-page novel is an exhaustively scathing critique of international colonialism that imposes vampire capitalism, a network of distorted power relations that survives by sucking the lifeblood of the people and the land. This is not a book of doom and despair if there is comfort in a vision of hemispheric revolution. Angelita, the Mayan revolutionary known as La Escapia, believes that "Marx had recited the crimes of slaughter and slavery committed by the European colonials who had been sent by the capitalist slavemasters to secure the raw materials of capitalism · human flesh and blood" (p. 315). By the end of the book, the dispossessed of the world · the homeless, veterans, and indigenous people · move independently toward the southern border of the United States for a final confrontation. Maps are important throughout Almanac precisely in proportion to how they overlay artificial boundaries onto the land. Maps, tools of capitalism, impose the illusion of individual ownership and national boundaries. Architect Alegría designs a palatial home built on the edge of the diminishing rain forest; Leah Blue has grand plans to build New Venice, a town of green golf courses and flowing canals, in the Arizona desert. Such selfish and arrogant misuse of the land reflects the Destroyer sensibility that land is only one of many resources to be exploited for short-term personal gain. Specific strengths and truths are within the land itself, Silko is reported to have said, and they one day will be heard. Just as many Native elders have said that the prophecies instruct the people to wait patiently for the colonizers to destroy themselves, so Silko suggests that all things European (not all Europeans) will pass away. By the end of the book, she makes it clear that the earth is really not in danger (although its inhabitants may be). Sterling, a Laguna Pueblo Indian who seems the closest thing to a voice for Silko in the novel, returns to the uranium mines located on the pueblo and muses that "humans had desecrated only themselves with the mine, not the earth. Burned and radioactive, with all humans dead, the earth would still be sacred. Man was too insignificant to desecrate her" (p. 762). This is an opinion she repeats in a collection of personal prose and nature photographs titled Sacred Water (1993). In Sacred Water, Silko seems to return to a more positive vision when she uses the hyacinth and datura as metaphors for the purifying capacities of the earth. Hyacinths "digest the worst sorts of wastes and contamination"; they can even "remove lead and cadmium from contaminated water" (p. 72). And the datura can "purify plutonium contamination" (p. 75). The pollutants from uranium mines and underground nuclear test sites and the chemicals and heavy metals from mines pollute the water. "But," concludes Silko, "human beings desecrate only themselves; the Mother Earth is inviolable. Whatever may become of us human beings, the Earth will bloom with hyacinth purple and the white blossoms of the datura" (p. 76). Although this may be considered a positive interpretation of the self-purifying capacities of Mother Earth as larger and more significant than mere polluting humans, it is optimistic only insofar as humans are seen as separate from the natural world. It would be inappropriate not at least to mention that the inclusive sense of the natural world elicited by most Native American writers challenges another western category, another binary opposition: the natural versus the supernatural. Rather than viewing them as opposites, what the West calls "supernatural" might better be understood as part of the natural, at least for those whose orientation and training prepare them to experience beyond the five senses or beyond what the West refers to as rationality. This may be why the spirit(ual) world is so evident in much Native American literature. Ghosts, transformations (of people into bears, for instance), and visitations are all part of an inclusive sense of the natural world. They are not borrowed literary devices, like magical realism, but a fundamentally different way of perceiving the world. For the Kiowa writer Momaday, a "deep, ethical regard for the land" is central to Indian identity and necessary for all humans. Such regard demands an expansive vision, considering not only the consequences of human actions seven generations into the future, as the Iroquois recommend, but also the ramifications of our actions throughout the entire (super)natural world. "We Americans need now more than ever before," he insists, "to imagine who and what we are with respect to the earth and sky" ("Man Made of Words," p. 166). To reconceive an "American land ethic," Momaday suggests that each individual observe the natural world with careful regard: Once in his life, a man ought to concentrate his mind upon the remembered earth.... He ought to give himself up to a particular landscape in his experience, to look at it from as many angles as he can, to wonder about it, to dwell upon it. He ought to imagine that he touches it with his hands at every season and listensto the sounds that are made upon it. He ought to imagine the creaturesthere and all the faintest motions of the wind. He ought to recollectthe glare of noon and all the colors of the dawn and dusk. (The Way to Rainy Mountain, p. 83) To concentrate on, to surrender to, to experience with all the senses in every season, to imagine and to remember the earth and their position on it are, for many Native American writers, essential acts of recuperating a connection to history and culture via a relationship with the earth. Selected Bibliography PRIMARY SOURCES John Bierhorst, ed., "The Night Chant," in Four Masterworks of American Indian Literature (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974); Joseph Bruchac, "The Circle Is the Way to See," in Story Earth (San Francisco: Mercury House, 1993), repr. in Family of Earth and Sky, ed. by John Elder and Hertha D. Wong (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994); Louise Erdrich, Love Medicine (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1984; new and enl. ed., New York: Harper-Perennial, 1993), "Where I Ought to Be: A Writer's Sense of Place," in New York Times Book Review (28 July 1985), The Beet Queen(New York: Holt, 1986), Tracks (New York: Holt, 1988), and The Bingo Palace (New York: HarperCollins, 1994); Rayna Green, ed., That's What She Said: Contemporary Poetry and Fiction by Native American Women (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1984); Linda Hogan, "The Kill Hole," in Parabola 13, no. 3 (1988), repr. in Family of Earth and Sky, ed. by John Elder and Hertha D. Wong (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), Mean Spirit (New York: Atheneum, 1990), "Walking," in Parabola 15, no. 2 (1990), and "What Holds the Water, What Holds the Light," in Parabola 15, no. 4 (1990). D'Arcy McNickle, The Surrounded (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1936; Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 1978); N. Scott Momaday, House Made of Dawn (New York: Harper & Row, 1968),The Way to Rainy Mountain (Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 1969), The Names: A Memoir (New York: Harper & Row, 1976), and "The Man Made of Words," in The Remembered Earth: An Anthology of Contemporary Native American Literature, ed. by Geary Hobson (Albuquerque: Red Earth Press, 1979), repr. in Family of Earth and Sky, ed. by John Elder and Hertha D. Wong (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994); Simon Ortiz, Woven Stone (Tucson: Univ. of Arizona Press, 1992); Leslie Marmon Silko, Ceremony (New York: Viking Press, 1977), Storyteller (New York: Seaver Books, 1981; New York: Arcade, 1989), "Landscape, History, and the Pueblo Imagination," in Antaeus, no. 57 (1986), repr. in Family of Earth and Sky, ed. by John Elder and Hertha D. Wong (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), Almanac of the Dead (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991), and Sacred Water (Tucson, Ariz.: Flood Plain Press, 1993); Luther Standing Bear, Land of the Spotted Eagle(Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1933; Lincoln: Univ of Nebraska Press, 1978); Brian Swann and Arnold Krupat, eds., I Tell You Now: Autobiographical Essays by Native American Writers(Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1987); James Welch, Winter in the Blood (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), and Fools Crow (New York: Penguin, 1986); Ray A. Young Bear, The Invisible Musician (Duluth, Minn.: Holy Cow! Press, 1990). ANTHOLOGIES Paula Gunn Allen, ed., Spider Woman's Granddaughters: Traditional Tales and Contemporary Writing by Native American Women (Boston: Beacon Press, 1989); Beth Brant, ed., A Gathering of Spirit: A Collection by North American Indian Women (Rockland, Maine: Sinister Wisdom Books, 1984; New York: Firebrand Books, 1988); George W. Cronyn, ed., American Indian Poetry: The Standard Anthology of Songs and Chants (New York: Liveright, 1934); Arthur Grove Day, ed., The Sky Clears: Poetry of the American Indians (New York: Macmillan, 1951; Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1964, 1971); John Elder and Hertha D. Wong, eds., Family of Earth and Sky: Indigenous Tales of Nature from Around the World (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994); Andrea Lerner, ed.,Dancing on the Rim of the World: An Anthology of Northwest Native American Writing (Tucson: Sun Tracks/Univ. of Arizona Press, 1990); Craig Lesley, ed., Talking Leaves: Contemporary Native American Short Stories (New York: Laurel, 1991); Duane Niatum, ed., Carriers of the Dream Wheel: Contemporary Native American Poetry (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), and Harper's Anthology of 20th-Century Native American Poetry (San Francisco: HarperSan-Francisco, 1988; Bernd C. Peyer, ed., The Singing Spirit: Early Short Stories by North American Indians (Tucson: Univ. of Arizona Press, 1989); Kenneth Rosen, ed., The Man to Send Rain Clouds: Contemporary Stories by American Indians (New York: Random House, 1975); Frederick W. Turner III, ed., The Portable North American Indian Reader (New York: Viking/Penguin, 1973); Alan R. Velie, ed., American Indian Literature: An Anthology (Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1979; rev. ed., 1991), and The Lightening Within: An Anthology of Contemporary American Indian Fiction (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1991). SECONDARY SOURCES Paula Gunn Allen, The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions (Boston: Beacon Press, 1986), and, as ed., Studies in American Indian Literature: Critical Essays and Course Designs (New York: Modern Language Association, 1983); Gretchen M. Bataille and Kathleen Mullen Sands, American Indian Women: Telling Their Lives (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1984); Peggy V. Beck and Anna L. Walters, The Sacred: Ways of Knowledge, Sources of Life (Tsaile, Ariz.: Navajo Community College, 1977); William Bevis, "Native American Novels: Homing In," inRecovering the Word, ed. by Brian Swann and Arnold Krupat (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1987); Joseph Bruchac, ed., Survival This Way: Interviews with American Indian Poets (Tucson: Univ. of Arizona Press, 1987); H. David Brumble III, American Indian Autobiography (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1988); Abraham Chapman, ed., Literature of the American Indians: Views and Interpretations (New York: New American Library, 1975); Laura Coltelli, ed., Winged Words: American Indian Writers Speak (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1990); Inés Hernández-Avila, "Relocations," in American Indian Quarterly 19 (fall 1995); Dell Hymes, "In Vain I Tried to Tell You": Essays in Native American Ethnopoetics (Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1981); Rudolf Kaiser, "Chief Seattle's Speech(es): American Origins and European Reception," in Recovering the Word, ed. by Brian Swann and Arnold Krupat (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1987); Karl Kroeber, ed., Traditional Literatures of the American Indian (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1981); Arnold Krupat, For Those Who Come After: A Study of Native American Autobiography (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1985), and, as ed., New Voices in Native American Literary Criticism (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1993). Kenneth Lincoln, Native American Renaissance (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1983); Lauren Muller, "Map Making as Speculation in Almanac of the Dead: Mapping the News" (unpub., 1994); Robert M. Nelson, Place and Vision: The Function of Landscape in Native American Fiction (New York: Lang, 1993); Alfonso Ortiz, "Look to the Mountaintop," in Essays on Reflection, ed. by E. Graham Ward (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973), and "Indian/White Relations: A View from the Other Side of the ‘Frontier,’" in Indians in American History: An Introduction, ed. by Frederick E. Hoxie (Arlington Heights, Ill.: Harlan Davidson, 1988); Louis Owens, Other Destinations: Understanding the American Indian Novel (Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1992); Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes, Travel Writing and Transculturation (London: Routledge, 1992); John Lloyd Purdy, Word Ways: The Novels of D'Arcy McNickle (Tucson: Univ. of Arizona Press, 1990); Jarold Ramsey, Reading the Fire: Essays in the Traditional Indian Literature of the Far West (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1983), and, as ed., Coyote Was Going There: Indian Literature of the Oregon Country(Seattle: Univ. of Washington Press, 1977); A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff, American Indian Literatures: An Introduction, Bibliographic Review, and Selected Bibliography (New York: Modern Language Association, 1990); Greg Sarris, Keeping Slug Woman Alive: A Holistic Approach to American Indian Texts (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1993); Brian Swann, ed., Smoothing the Ground: Essays on Native American Oral Literature (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1983); Brian Swann and Arnold Krupat, eds., Recovering the Word: Essays on Native American Literature (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1987); Gerald Vizenor, ed., Narrative Chance: Postmodern Discourse on Native American Indian Literatures (Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 1989); Andrew O. Wiget, Native American Literature (Boston: Twayne, 1985), and, as ed., Critical Essays on Native American Literature (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1985); Hertha D. Wong, Sending My Heart Back Across the Years: Tradition and Innovation in Native American Autobiography (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1992); Charles L. Woodard, ed., Ancestral Voice: Conversations with N. Scott Momaday(Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1989). Source Citation Wong, Hertha D. "Nature in Native American Literatures." American Nature Writers. Ed. John Elder. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1996. Literature Resource Center. Web. 1 Sept. 2010. Document URL http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?&id=GALE%7CH1479000825&v =2.1&u=epfl&it=r&p=LitRC&sw=w Gale Document Number: GALE|H1479000825