Decision-Making about New Health Interventions

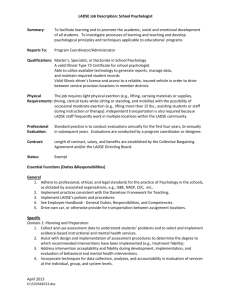

advertisement