Urolithiasis - The Brookside Associates

advertisement

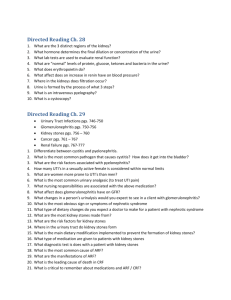

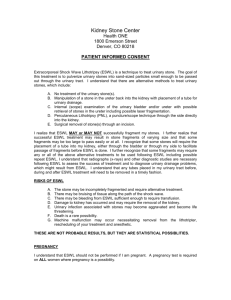

General Medical Officer (GMO) Manual: Clinical Section Urolithiasis Department of the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Peer Review Status: Internally Peer Reviewed (1) Introduction Urinary calculi, commonly referred to as kidney stones, are a relatively common disorder affecting one to five percent of the population in industrialized countries. Several population studies estimate the lifetime risk for stone formation in white males approaches twenty percent, while that of females is closer to five to ten percent. The recurrence rate for urinary stones has been reported to be as high as fifty percent in the first 5 years after the initial diagnosis. Because of the high prevalence of these calculi, the frequency of recurrence, and the potential for significant pain and infection with the passage of the stone, an understanding of calculus disease is essential for military medical providers. (2) History A thorough history, including family history, should be elicited from the patient. The patient should be queried as to the onset, location, duration, and character of the pain. The presence of any fever, burning on urination, irritative voiding symptoms, and a urinalysis needs to be documented. The pain is often described as sharp, colicky in nature, and may be associated with nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and malaise. Any past history of stones, along with the methods of treatment and the stone composition, should be sought. A history of inflammatory bowel disease, gout, periods of dehydration, and the presence of certain inherited diseases, such as renal tubular acidosis or cystinuria, should be elicited. (3) Correlation of pain and presentation The presentation of urolithiasis is often dependent upon the location of the calculus within the collecting system. Small, non-obstructing stones within the calyces of the kidney may be found incidentally on radiographs or may present with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. As the stone grows or leaves the renal pelvis it may become obstructed at the ureteropelvic junction, the first narrowing of the collecting system. If obstruction occurs, the pain may be intermittent, corresponding to the blockage of urine flow from the renal pelvis. The pain may be localized to the ipsilateral flank or costovertebral angle. If a urinary tract infection accompanies the obstruction, pyelonephritis or gram negative sepsis may result. A stone small enough to pass into the ureter may produce ureteral colic, an acute, sharp, spasm like pain located in the flank, or hematuria. As the stone progresses down the ureter to the level of the pelvic brim and iliac vessels, the pain will remain sharp and colicky in nature, corresponding to peristalsis of the ureter. The pain may radiate to the lateral flank and abdominal area. It may be associated with nausea and vomiting. Patients will often describe a waxing and waning quality to the pain with periods of relief from the pain as the ureter relaxes. As the stone passes to the distal ureter and nears the bladder, the pain retains its same character but may intensify. The patient may describe the pain radiating to the ipsilateral groin, scrotum, or labia. Irritative voiding symptoms may intensify with the stone in the intramural portion of the ureter. (4) Other Symptoms of Urolithiasis Most patients with urinary calculi will present with severe colic and may be in significant distress. In contrast to patients with acute peritonitis, those with ureteral stones will frequently be unable to find comfort in one position. Diaphoresis, tachycardia, and tachypnea may be present. It is not unusual for the patient to have a low-grade fever, but those temperatures above 101.5F are often associated with a urinary tract infection. On abdominal exam, the bowel sounds may be hypoactive. The abdomen needs to be examined carefully to exclude any cause of a surgical abdomen. Flank tenderness may be elicited. Females must undergo a pelvic exam to rule out any gynecologic etiology of the symptoms. (5) Differential Diagnosis It is not unusual for ureteral colic to be associated with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal complaints, thus making the diagnosis often unclear. Abdominal distension may result from a reflex ileus. The passage of a stone may not be as dramatic as described above and may only be associated with a vague complaint of abdominal pain. The pain can be low grade and mimic other etiologies of visceral pain. It is therefore imperative to consider other causes of surgical abdomens in the differential diagnosis. Other diagnoses would include acute appendicitis, peritonitis, cholecystitis, diverticulitis, salpingitis, ectopic pregnancy, colitis, and gastroenteritis. (6) Laboratory Studies Urinalysis and culture are mandatory for any patient suspected of having urolithiasis, and a pregnancy test must be obtained on females undergoing radiographic examination. The urinalysis will frequently show microscopic hematuria. Gross hematuria is not uncommon. The absence of hematuria does not exclude the presence of a stone. Pyuria may be present even in the absence of infection. The urine pH and presence of crystals within the urine may provide clues as to the type of stone causing the pain. (7) Radiologic Studies Approximately ninety percent of all renal stones are radiopaque and therefore visible on plain radiographs. Calcifications that may be confused with urinary calculi include calcified lymph nodes, gallstones, foreign bodies, recently ingested pills, and pelvic phleboliths. Intravenous urography can confirm the diagnosis of a urinary calculus, but this study must not be performed in patients with known contrast allergies or renal failure. The urogram is performed by administering 1cc/kg of intravenous contrast material and then performing serial radiographs to document excretion of contrast from the kidneys to the bladder. Though anaphylaxis is rare, one should be prepared to attend to the patient quickly if a contrast reaction occurs. Plain radiographs should be taken before giving the contrast agent and films should be taken at five, ten, and twenty minutes. The time between subsequent films should be doubled until the collecting system is visualized down to the level of the obstructing stone. The most common finding in acute colic is a delay in visualization of contrast in the collecting system on the affected side. Oblique views may be necessary for a stone near the bladder. Post void films can also be useful in visualizing distal ureteral stones. (8) Management Guidelines Management of the patient with a urinary calculus depends on the size and location of the stone, the presence or absence of associated infection, the presence of a solitary kidney, and the degree of symptoms. The great majority of stones will pass spontaneously with no residual damage to the urinary system. Ninety percent of stones less than 4mm will pass spontaneously, whereas fifty percent of stones 4mm-6mm will pass on their own. Less than twenty percent of stones larger than 6mm will pass without some intervention. The presence of a stone is not an emergency and in almost all cases, the patients can be managed expectantly. This consists of hydration and the liberal use of analgesics. The patient with severe nausea and vomiting will require intravenous hydration and parenteral narcotics. Commonly used analgesics include ketorolac (Toradol), Demerol, morphine, and oral narcotics/analgesic combinations. The concurrent use of antiemetics is often useful. These patients may require frequent intravenous narcotics to maintain control of the pain. With adequate hydration and pain control, most patients will do well and not require transfer to a hospital for intervention. (9) When to MEDEVAC The general guidelines for intervention and surgical management of a urinary calculus would include: (a) a fever above 101.50 F with a known urinary tract infection (b) severe pain unresponsive to oral or parenteral narcotics (c) intractable emesis (d) complete obstruction of a solitary kidney (e) the inability to manage the patient due to operational requirements It is rarely necessary to emergently evacuate a patient from a ship or deployed unit because of a urinary calculus. Obstruction of the kidney in the absence of a urinary tract infection is not an emergency and typically no permanent damage to the kidney will result from sterile obstruction, unless it is long standing (i.e. weeks to months). If the patient develops a fever suggestive of a urinary tract infection, the initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics is advisable and should continue until the patient receives definitive management. The patient should be maintained well hydrated and given analgesics as required. At the earliest safe opportunity, the patient should be evacuated with a medical attendant to the nearest medical facility with the ability to place a ureteral stent or obtain percutaneous access to drain the kidney. (10) Summary Urinary calculi are a common disorder and can present with both dramatic and subtle findings. In most cases, no intervention is required other than supportive measures. However, if the patient has urinary obstruction with an infection, a solitary kidney, or if the pain and emesis are uncontrollable, then evacuation to a facility for definitive management is needed. Submitted by CAPT M. Melanie Haluszka, MC, USN, LCDR Brian K. Auge, MC, USN, and LT Timothy F. Donahue, MC, USNR, National Naval Medical Center, Bethesda (1999).