religious expression in australia 1945 to the present

advertisement

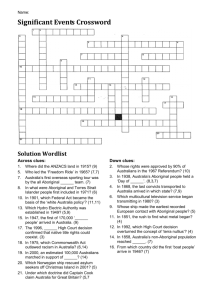

RELIGIOUS EXPRESSION IN AUSTRALIA 1945 TO THE PRESENT OXFORD TEXT THE CHANGING PATTERN OF RELIGIOUS ADHERENCE Census data A question on religious affiliation has been asked in every census taken in Australia, with the voluntary nature of this question being specifically stated since 1933. In 1971 the instruction ‘if no religion, write none’ was introduced. This saw a seven-fold increase from the previous census year in the proportion of people stating they had no religion. Since 1971 this proportion has progressively increased to about 19% in 2006. Table 9.1 provides a summary of the major religious affiliations at each census since 1901. TABLE 9.1 MAJOR RELIGIOUS AFFILIATIONS, 1901–2006 ACTIVITIES Questions on census data in Table 1: Major religious affiliations, 1901–2006. 1. In 1947 what was the Anglican Church still being referred to as? 2. In what year were there 10 percentage points difference between Anglican and Catholic affiliation? 3. What is notable about the Anglican and Catholic figures in 1986? 4. In which year did the total number of people responding to the census number 17 753 800? 5. Describe the difference in the ‘other’ religious affiliations between 1947 and 2006. 6. Explain the increase in percentage points in the ‘no religion’ category. 7. Describe the pattern of religious affiliation in the category ‘other’ between 1947 and 2006. 8. Why do you think people ‘object to state’ their religious affiliation? 9. What are the most significant changes in religious affiliation between 1947 and 2006? 1 TABLE 9.2 CHANGE IN RELIGIOUS AFFILIATIONS, 1996–2006 ACTIVITIES Questions on data in Table 9.2: Change in religious affiliations, 1996–2006. 1. What does it mean when there is a negative growth rate? 2. Identify the denominations of Christianity that remained constant between 1996 and 2006 (that is, those that have changed between 0 and 0.1 percentage points). 3. Is there anything that surprises you here? 4. Give three examples of ‘Other Christian’ religions. 5. What denominations do you think might be included under ‘Eastern Orthodox’? 6. Explain the percentage increase in ‘Non-Christian’ traditions between 1996 and 2006. 7. Why do you think Buddhism has increased more than Islam? 8. Give three examples of ‘Other Non-Christian’ religions. 9. How can the Lutherans decrease in percentage points between 1996 and 2006 but still show positive growth? 10. Write a paragraph to describe the changes in religious affiliation of ‘Non-Christian’ religion between 1996 and 2006. 2 TABLE 9.3 2006 CENSUS—RELIGIOUS AFFILIATIONS BY STATE/TERRITORY • Christianity remained the dominant religion in Australia, although non-Christian religions continued to grow at a much faster rate. Since 1996, the number of people reporting that they are Christian grew from around 12.6 million to 12.7 million, but as a proportion of the total population this number fell (from 71% to 64%). Over the same period, those affiliated with non-Christian faiths increased from around 0.6 million to 1.1 million people, and collectively accounted for 5.6% of the total population in 2006 (up from 3.5% in 1996). • Australia’s three most common non-Christian religious affiliations were Buddhism (2.1% of the population), Islam (1.7%) and Hinduism (0.7%). Of these groups, Hinduism experienced the fastest proportional growth since 1996, more than doubling to 150 000, followed by Buddhism, which doubled to 420 000. • People affiliated with the main non-Christian religions were clustered in Sydney and Melbourne. I 2006, 47% of Hindus and 47% of those affiliated with Islam lived in Sydney. Around 46% of Australians affiliated with Judaism lived in Melbourne. Similarly, the most common locations o people affiliated with Buddhism were in Sydney (37%) and Melbourne (30%). Source: ABS 2006 Census ACTIVITIES Questions on data in Table 9.3: 2006 Census—Religious affiliations by state/territory. 1. What do you think is meant by the category ‘inadequately described’? 2. Why do you think the figures for Judaism are higher in New South Wales and Victoria than elsewhere? 3. Why do you think the Northern Territory has the greatest percentage of ‘Other Religions’? THE CURRENT RELIGIOUS LANDSCAPE Christianity as the major religious tradition in Australia Though Australia is rapidly becoming a multi-faith society, the majority religious affiliation is still strongly Christian, as can been seen in the census data presented above. The Anglican Church and the Roman Catholic Church still hold the dominant roles, numerically speaking. Although the Anglican Church still maintains ties to Britain, these have weakened considerably. A new constitution passed in 1962 dissolved legal ties to Britain. This meant that the Church of England in Australia was now free to determine all matters of faith, worship and discipline for itself. In keeping with the aims of independence, the Church of England in Australia changed its name in 1982, dropping the reference to England and calling itself the Anglican Church of Australia. 3 Other efforts to forge a distinctly Australian idiom among Anglicans resulted in the publication of An Australian Prayer Book by the national governing body, the General Synod, in 1978. This followed the publication of The Australian Hymn Book in 1977, an initiative sponsored by five Protestant denominations. The modernisation of the Anglican prayer book continued, amidst much controversy, culminating in the publication in 1995 of A Prayer Book for Australia, notable features of which are inclusive language, prayers for Aboriginal reconciliation and the adoption of a broad range of metaphors for describing God. In recent years the proportion of Anglicans has continued to decline. In 1981 Anglicans represented 26.1% of the Australian population, but by 2006 their presence declined to 18.7%. The Anglican Church no longer holds the greatest proportion of Christian adherents. That place has now been taken by the Roman Catholic Church, which in 2006 held 25.8% of the population. The Australian Catholic community has changed considerably from its Anglo-Celtic origins. From its pre–Second World War percentage of 17.5% of the Australian population, the post-war Catholic community rose to 20.7 percent, with Europe contributing many nationalities under the Catholic banner, such as Croatians, Germans, Italians, Spaniards and Maltese. In the roughly ten-year period between 1975 and 1984, the migration of Indo-Chinese refugees and migrants from the Philippines brought a sizeable Asian contingent into the Catholic Church. Over 30 ethnic groups constitute the Catholic Church in Australia today. The Catholic Church now claims the largest number of adherent of all denominations in the Australian religious landscape. Among the Protestant churches is the relatively newly formed Uniting Church in Australia, founded in 1977. Initially the Uniting Church was made up of Methodists, Presbyterians and Congregationalists. Their unity made them the largest of the reformist tradition of Protestantism in Australia. Now the third largest Christian denomination in Australia, the Uniting Church constitutes a significant voice in the Australian religious landscape. One of the consequences of union is the variety of worship forms found in the Uniting Church, from formal liturgical styles to informal and creative forms of worship. Like its Anglican and Catholic cousins, it uses a three-year lectionary, which not only gives a sense of continuity within each congregation but also a sense of relationship with other Christian denominations. Ministry in the Uniting Church recognises that both men and women can be ‘called to preach the gospel’. The church is committed to issues of social justice through its Board of Social Responsibility and a range of agencies, projects, hospitals and senior citizens’ institutions. Unlike most Christian churches in Australia, the Pentecostal churches have shown significant growth, with 185 000 attending on a typical Sunday. Organised around influential preachers and their individual churches or groups of churches, Pentecostal Christianity is distinctive for its profusion of churches. As a consequence there is a great tendency for followers to ‘switch’ between churches. The practice of enthusiastic prayer, the use of contemporary music, the staging of large stadium events and the avoidance of formalised liturgy have made Pentecostal churches particularly attractive to the younger generation. Churches that belong to this tradition include the Assemblies of God (which has well over 500 congregations), the Christian Revival Crusade, the Foursquare Gospel Churches and the Christian and Missionary Alliance. Further Pentecostal churches, many of which refer to themselves as ‘community centres’, include Hills Christian Centre in Baulkham Hills and the Christian Growth Centre in Sutherland, both in New South Wales. Other Pentecostal groups include the Bethesda Movement and Associated Christian Assemblies International. The impact of immigration We have already seen that the Christian church in Australia is an immigrant church, with the convict years contributing to both Catholic and Anglican denominations. The arrival of people of other religious traditions added to this Christian expression of faith in the early years of the colony; however, their numbers were relatively small and had little impact on the overall religious landscape. It wasn’t until the 1900s that this picture began to show significant change. In the space of a few short years, Turkish-born Australians grew from 2475 in 1966 to ten times that number in 1981. By 1986, the Muslim Turkish population (including children born of Turkish parents) was about 50 000. Muslim migrants also came from Lebanon, particularly after civil war began there in 1975. Although Lebanese Muslims had already settled in south Sydney in the 1960s, a significant 4 number—about 1400—migrated to Australia between 1975 and 1977. Currently there are approximately 35 000 Lebanese Muslims in Australia, of whom about 20 000 are Sunni, 11 000 Shi‘a, and 5000 Druze and Alawi Muslims. Migrants from other Muslim countries such as Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Jordan and Indonesia have also settled in Australia. The total Australian Muslim population is composed of migrants from about 35 countries. Buddhism There has been a considerable increase in the numbers of Buddhists immigrating to Australia since the suspension of the ‘White Australia’ policy in the mid-1960s. Before this, however, the Englishman Leo Berkeley, a keen protagonist of Buddhism, had migrated to Australia from London. The year was 1947. He soon formed a society for those interested in Buddhism, holding lecture evenings with guest speakers. The year 1950 saw the founding of the World Fellowship of Buddhists and the subsequent Australian visit of the Buddhist nun Dhammadinna (1881–1967), who came to spread Buddhist teachings. An American convert, she gave impetus to the formalisation of Berkeley’s society, which was formally constituted as the Buddhist Society of New South Wales on 4 May 1953. It continues to this day as the oldest Buddhist society in Australia. A year later saw Buddhist societies being founded in both Queensland and Victoria. The Buddhist Federation of Australia was formed in 1958, taking over from the New South Wales society as the organisational member of the World Federation of Buddhists. These early Western-based developments of Buddhism stand in stark contrast to the later expressions of Buddhism in Australia, which came on the back of immigrants. In 1973 all barriers to non-Europeans were finally removed and Australia became attractive to Asian migrants. Currently there are well over 200 000 ethnic Chinese in Australia, drawn from several Asian countries including China, Papua New Guinea, Singapore, Vietnam and Malaysia. Many of the Chinese immigrants from Hong Kong and Singapore, both previous British colonies, tend to be Christian. The Vietnamese account for the largest ethnic group of Buddhists in Australia. Sri Lankans, Indians, Tibetans and Nepalis, Thais, Burmese, Cambodians and Laotians are represented in significant numbers among Australia’s various Buddhist communities. Indo-Chinese migrants began arriving in 1975. There are over 35 000 Vietnamese Buddhists in Australia, coming from both Theravada and Mahayana traditions—the Mahayana followers bringing their own monks and establishing their own organisations. Smaller numbers have arrived from Laos and Cambodia. These Theravada Buddhists have tended to join already existing groups. Census figures indicate that during the decade 1981 to 1991, Buddhism was the fastest-growing religion in Australia, with an increase of over 100 000 to nearly 140 000 people. Today the Buddhist community in Australia is very diverse, with representatives from the Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana (Tibetan) traditions as well as significant numbers of Zen and Pure Land Buddhists. The popularity of the Dalai Lama has meant that Tibetan Buddhism has taken on a higher profile in Australia. Judaism After the Second World War, in which almost six million Jews were killed by the Nazis throughout Europe, Jewish survivors made their way to Israel or Western countries such as Australia. Between 1945 and 1960 approximately 30 000 Jews arrived from Europe (excluding Britain), joining the already long-established Australian Jewish communities of Melbourne and Sydney. Almost parallel to the European migration, Jews from Egypt, Iraq, Iran and even India migrated to Australia. This was mainly in the 1940s and 1950s. These were Sephardi Jews who, unlike the European Ashkenazi Jews, have an Arabic-Spanish tradition of prayers, music and religio-cultural customs. Some Sephardi Jews intermarried and integrated with Ashkenazi Jews and adopted their tradition, but many attempted to remain distinct, gathering in their own synagogues in the cities of Sydney, Melbourne and Perth. Diversity and unity As can be seen, contemporary Australia is becoming increasingly diverse in its religious composition. The presence of synagogues, Buddhist temples, Eastern Orthodox churches, mosques and Hindu 5 temples has changed the Australian religious landscape, diminishing in some areas the predominance of Anglo-Celtic Christianity. But the diversity has not developed without resistance, at first officially through the ‘White Australia’ policy and then in other unofficial ways (such as protests against the building of mosques and their associated schools, and notably against the building of a largely underground Hindu temple near Minto in New South Wales). But before it is concluded that hostilities are the result of recent migration, it should be remembered that conflict has also been a significant feature of Catholic and Protestant relations in Australia. Discriminatory hiring policies were the norm before they were widely rejected in the late 1960s and early 1970s and made illegal with the passing o antidiscrimination legislation. As a result of this wave of Jewish migration, the Australian Jewish community has become one of the more distinctive of the Jewish communities outside Israel. Sadly, it is at the times when as a nation Australians must try to come to terms with tragedy that religious traditions show the world that unity within diversity is possible. MODERN DEVELOPMENTS IN AUSTRALIAN RELIGION Denominational switching ‘Denominational switching’ is one of several factors influencing the face of Christianity in Australia today. The term is used to describe the phenomenon of people changing from one denomination to another. Although a feature of Christianity, as a process it can occur within or across the boundaries of any religious tradition. Most commonly seen in Protestant churches, denominational switching enables a person to find a spiritual ‘home’ where he or she feels most at ease with the style of worship and the views put forward by the ministerial team of the parish. It can be likened to the concept of shopping around for the best deal and is often poorly regarded by more conservative Protestants—unless, of course, it means welcoming a new member into their congregation. In order to visualise the effect of denominational switching, it is necessary to look at the census data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). The National Church Life Survey (NCLS) regularly produces its own material from extensive surveys of worshipping Christians. Coupled together, these survey results give us a fairly accurate picture of the religious landscape. One of the facts learnt from these survey results is that in many cases loyalty is to parish first and denomination second, especially among the younger members. Leaving the churches of their parents, these people are seeking places where the average age of congregations is younger, the music modern and the message clear. Many seek Pentecostal or charismatic churches to the detriment of the older and more traditional congregations. ACTIVITY Look up the ABS census data and describe the changes in adherents in the different Protestant denominations. Can you find out the age breakdown for these changes? By consulting National Church Life Survey information, outline what you think may be the reasons for these changes. The rise of New Age religions It was the counterculture movement of the 1960s that opened the way for the New Age movement, which can be described as ‘a loosely structured network of individuals and organisations holding new visions of enlightenment and harmony while subscribing to a common worldview’ (Ron Rhodes, New Age Movement [1995]). The counterculture movement was a time when people became open to new ways of thinking and doing. These were seen in people’s acceptance of new religious beliefs and cosmologies. Hinduism and its different deities became popular, ‘… loyalty is to parish first and denomination second, especially among the younger members.’ prompting people to think again about the divine. For example, many saw the countercultural way of life of the Hare Krishnas as appealing. Considerable diversity is found within the movement today, encompassing a great number and variety of religious and secular philosophies. Included are holistic health professionals, ecologists, 6 political activists, educators, human potential advocates, goddess worshippers, reincarnationists, astrologers and many others. ‘New Agers’, as they are often referred to, have certain characteristics in common, such as the belief that it is possible to draw the ‘truth’ from a variety of sources. This often results in a syncretic philosophy informing their worldview. Rather than being exclusivist in their approach, New Agers tend to be inclusive, with all reality being seen as both interrelated and interdependent. New Age spirituality is multifaceted, drawing on Eastern meditation, altered states of consciousness, reincarnation, spiritualism and many other sources. These spiritualities are affirming rather than guilt laden. Within this movement are the neo-pagans, who have revived the paganism of old that rejected organised religion, male domination and the abuse of nature. Like-minded people include goddess worshippers, who seek the inner divinity that they believe is present in everyone. ACTIVITY Each year Sydney hosts the ‘Mind, Body, Spirit Festival’. Find out when and where this is held. What is the purpose of this festival? Is it correct to say it is a celebration of New Age spiritualities? Explain your response. Secularism There is a general trend in modern society to replace religious belief and practice with other kinds of knowledge and activity, drawn largely from the secular disciplines of sociology, psychology and the hard sciences. Secularism is when religious perspectives have been abandoned in favour of a more nonreligious response to life’s questions. Many see it as an abandonment of religion in order to move to a more hedonistic stance. Others see it as an attempt to abandon attitudes that instil guilt in the individual. Still others would see secularism as an option that excludes any form of religious adherence. Sociologist of religion J. M. Yinger points out that secular philosophies such as Positivism with its faith in science, Marxism with its faith in revolution and Freudianism with its faith in psychoanalysis serve as secular alternatives to religion, not as religions in themselves. But he also points out that each only ever succeeds in providing a partial response to the question of the human condition. Alternatively, there need not be anything to replace a religious stance, but simply an abandonment of those concerns that the secularist sees as restricting—perhaps almost in the sense of reductionism, the abandonment of that which is no longer seen as relevant to the comfortable life in modern-day society. ACTIVITIES 1. In your own words write a definition of ‘secularism’. 2. Your friend does not take the subject ‘Studies of Religion’ and is puzzled by your use of the term ‘secularism’. How would you explain it to them? 7 RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE IN MULTI-FAITH AUSTRALIA ECUMENISM AND ECUMENICAL MOVEMENTS One of the significant features of post-war Australian Christianity is its development of ecumenism, stressing the common values and teachings that prevail across the many churches and denominations making up the Christian world. It is both a relational and dynamic concept, extending beyond the fellowship of Christians and churches to the human community within the whole of creation. It is the transformation of the inhabited earth into the living household (oikos) of God, that remains the calling of the ecumenical movement. • The Catholic Church defined the term ‘ecumenical movement’ in its Decree on Ecumenism (1961) as ‘the initiatives and activities planned and undertaken … to promote Christian unity’. • The Orthodox churches have been participants from the beginning and talk about ‘ecumenism I time’—the rediscovery of the shared history and ethos of all Christians. At the Third Assembly of the WCC (World Council of Churches) in 1961 (New Delhi) they stated, ‘the immediate objective of the ecumenical search is a reintegration of the Christian mind, a recovery of the Apostolic Tradition, a fullness of Christian vision and belief, in agreement with all ages’. • The churches of the reformed traditions (e.g. the Dutch Reformed Church and the Presbyterian Church) have professed no common understanding of ecumenism. Some would define it as the external relations between churches, others as the coming and being together of churches, and still others the manifestation of Christian concern for a world community in justice and peace. • Modern examples of the ecumenical movement are: the Taizé community in France the formation of the Uniting Church in Australia the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. The Biblical Justification for Ecumenism • The vision in John’s Gospel (17:21): ‘that they may all be one … so that the world may believe.’ • God’s plan ‘for the fullness of time, to gather up all things in him [Christ], things in heaven and things on earth.’ (Ephesians 1:10) Characteristics of Ecumenism • The uniting of professing Christians of all denominations • Cooperation across denominations • Focus on things in common. Although the foundations of ecumenism were set in the early 1900s, it wasn’t until the formation of the World Council of Churches in 1948 and the groundswell of the 1960s that it became a movement within the Christian church that drew people’s attention. The Greek term oikoumene is synonymous with the ecumenical movement. It is a word for ‘the whole inhabited earth’ and was first used to mean ‘ecumenical’ in a statement from the World Council of Churches in 1951. MILESTONES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT 1910 World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh 1921 Formation of the International Missionary Council 1925 Universal Christian Conference of Life and Work (Stockholm) 1927 World Conference on Faith and Order (Lausanne) 1948 First assembly of the World Council of Churches (Amsterdam) brings together Protestants, Eastern Orthodox (including Russian Orthodox) and Old Catholic bodies 1960 The Vatican formally recognises the existence of the ecumenical movement, establishing the Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity 1961 The World Council of Churches unites with the International Missionary Council 1962–65 Protestant and Eastern Orthodox observers are invited to the Second Vatican Council 1964 The Second Vatican Council’s Decree on Ecumenism encourages Catholic dialogue with Protestant and Orthodox churches 1966 Pope Paul VI meets with the Archbishop of Canterbury 1968 Fourth Assembly of the World Council of Churches sees Protestants, Orthodox and Catholics working together 1969 Pope Paul VI visits World Council of Churches headquarters in Geneva 8 1995 Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Ut Unum Sint reaffirms the Roman Catholic Church’ commitment to Christian ecumenism 1999 Pope John Paul II becomes the first Pope to visit Orthodox nations 1999 Catholics and Lutherans sign a joint declaration on the doctrine of justification, resolving some of the issues that led up to the Reformation The National Council of Churches in Australia In Australia, state-based ecumenical councils as well as the National Council of Churches in Australia (NCCA) seek to voice common concerns to the government on issues that directly affect Christian life. In 1994 the Catholic Church joined the already strongly functioning Australian Council of Churches and so the National Council of Churches in Australia came into being. [The word ‘ecumenical’] is properly used to describe everything that relates to the whole task of the whole Church to bring the Gospel to the whole world. It therefore covers … both Unity and Mission in the context of the whole world. (World Council of Churches Central Committee, August 1951) Changing alliances—religion in Australia today One of the best religious developments in Australia during the last half of the 20th century is the growth of ecumenism, a growth in love, knowledge and cooperation between the Christian Churches. Ecumenism has now become so widely accepted and taken for granted that younger Christians— people born after the 1960s—with their generally poor knowledge of history are sometimes surprise to learn that dialogue and cooperation between the different Christian denominations, between Catholics and Protestants, between the Orthodox and Catholics is a relatively recent phenomenon, the exception rather than the rule in the history of post-Reformation Christianity, and indeed for most of the time since the 1054 rupture between Rome and Constantinople … The weekend news reports told us of the latest riots in Northern Ireland between Protestants and Catholics. Indeed part of the Australian achievement is that we are so different from Northern Ireland … In 1984 I was in charge of a wonderful Irish-Australian parish in western Victoria, where the Catholic majority lived in prefect harmony with their non-Catholic neighbours, even if there was not always perfect peace between the different constituent villages of the parish. That year saw the first ever ecumenical service, held in the Anglican Church, which was extremely well attended by both sides. One of the Catholic men mentioned to me that he had been to this Anglican Church only once before, as a child to stone its roof. These examples serve to remind us of how far we have come and how much has been achieved. Although it is impossible to imagine an about turn away from ecumenism they also serve as a caution against taking this achievement too much for granted. (Extracts from the Halifax-Portal Lecture, May 2002 by Cardinal George Pell, Archbishop of Sydney) ACTIVITY Read the above extracts from the 2002 Halifax-Portal Lecture. (The entire lecture can be found on the Archdiocese of Sydney website). Using dot points outline the major points that Cardinal Pell makes in this portion of his lecture. The NSW Ecumenical Council The NSW Ecumenical Council is a network of 16 Christian churches throughout New South Wales and the Australia Capital Territory. It aims to promote the working together of Christian churches. The council works by three major principles: 1. To maintain ‘the unity of the Spirit in the bonds of peace’ (Ephesians 4:3) 2. To be committed to the gospel and to proclaiming it together 3. To live out the implications of the gospel for service in the world. The life of the NSW Ecumenical Council is centred on the unity and core truths of God in Jesus Christ. ACTIVITIES 1. Look up the following New Testament references containing the word oikoumene (inhabited world). What can you learn about oikoumene from them? • Luke 4:5–7 • Luke 2:1 • Acts 17:6 • Revelation 16:14 • Hebrews 2:5 9 2. Research the Taizé Movement of France. Who was Brother Roger? What is the purpose of the community? What is the composition of the community? Who visits the community? How is the liturgy of the community structured? Why do they use Latin in many of their hymns and choruses? 3. Australian churches celebrate the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. What is it and when is it held? Who celebrates it and what are some of the activities that are undertaken? INTERFAITH DIALOGUE Interfaith dialogue can no longer be the luxury of a few. Positive relationships need to be established among the religious traditions themselves. Such dialogue must become the catalyst for personal, social and cultural transformation. Catholic theologian Dr Gerard Hall SM states eight facts as to why interfaith dialogue is essential. 1. We live in a postmodern world in the sense that no single religion, culture, system or ideology has any convincing claim to be the one voice of truth. 2. We live in a democracy so that everyone has the right to present and defend his/her own system of beliefs and practices—even if we consider these to be inferior or in error. 3. We live in a secular society which is, at best, ambivalent about the role of religion—especially organised religion—in politics and the affairs of state. 4. We live in a global world in which our national identities in no way preclude our responsibilities for the well-being of all humanity and the one earth we share. 5. We are yet to grasp the full reality that Australia is a pluralistic, multicultural, multi-religious society in which dialogue among people of different traditions and with indigenous peoples is a requirement of social cohesion. 6. Spirituality, truth and goodness are not the domain of religion alone so that the religions need to be open to dialogue with indigenous, secular and non-religious voices. 7. The religious traditions have a particular responsibility in promoting strategies that enable dignity and justice for Australia’s first peoples and other marginalised groups (including more recent victims of governmental policy such as refugees, asylum seekers and the mentally ill). 8. Finally, dialogue is rooted in the nature and dignity of the human person and is ‘an indispensable step along the path towards human self-realisation … both of each individual and of every human community’ [Ut Unum Sint, n. 28]. An example of interfaith dialogue Dialogue between Christian groups is complemented by dialogue between religious traditions. For example, the Catholic Church’s commitment to maintaining an open dialogue with other faiths bore fruit in 1992 with its Guidelines for Catholic–Jewish Relations, produced under the auspices of the Bishops’ Committee for Ecumenical and Interfaith Relations of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference. The establishment in 1991 of the Australian Council of Christians and Jews has also fostered understanding between Christians and Jews and has countered anti-Semitism. One of the council’s most significant achievements is its formulation of a set of guidelines for Christian teachers and preachers that is intended to help them deal more sensitively with various passages in the New Testament that have traditionally been used against Jews and Judaism. Entitled Rightly Explaining the Word of Truth, the guidelines were developed with the cooperation of the heads of the Anglican, Roman Catholic and Uniting Churches, as well as other Christian denominations such as the Lutheran Church. Other independent interfaith associations have emerged in Australia, the best known being the World Council on Religion and Peace (WCRP) composed of representatives from the major religious traditions. The WCRP was the major recipient of a 1995 federal government grant in honour of the United Nations’ ‘Year of Tolerance’. Occasional resistance to other faith traditions is part of the reality of religiously diverse societies, but the predominant trend in Australia is a ‘live and let live’ ethic. In some cases a profound interest in learning about other groups is evident. ACTIVITY Internet research: Read the paper by Gerard Hall SM (‘The call to interfaith dialogue’, Australia EJournal of Theology, Issue 5, August 2005 [available online]). Select ten points that you think aid in the understanding of interfaith dialogue. Compare these with the points other students in your class have selected and as a class make a list of the ten most important points. 10 ABORIGINAL SPIRITUALITIES RECONCILIATION AND RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS IN THE PROCESS OF Aboriginal theology offers a vast spectrum of styles, ranging from the ‘traditional’ (or non-Western) to the ‘Aboriginal’ (or post-Western). Each of these reflects a differing measure of ‘encounter’ with European missions and theologies, and each has its own characteristics, limitations and contributions. Western Christianity’s impact on Aboriginal society The history of the encounter between traditional Aboriginal religion and Western Christian mission theology provides a framework for understanding how the various forms of Aboriginal theology are expressed today. The history of contact between Aboriginal and Western cultures is full of racism, classism, sexism and other forms of colonial, expansionist oppression—with the Aboriginal people bearing the brunt of the violence. The church was very much a part of this assault, drawing its personnel from the same society, and its theology from the same lines of thought and analysis, as the European invaders who stole the continent by force of arms and legal hocus-pocus. The church preached the language of love, yet it enforced ‘mission policies’ based on hate, fear, violence, division and denominationalism. Church and state worked together, and the results of this two-pronged onslaught have been nothing short of genocidal. Aboriginal people’s experiences of the transcendent were expected to be limited to Western understandings. Indeed, their expressions of God, church, faith and life were assimilated into Western expressions. Most European ‘Christians’ actually came to take the land, and preached falsehoods and heresies to Aboriginal people in order to rationalise the ‘takeover’. One of the most notorious examples of this Western theological deceit across Australia was the teaching of the Hamitic curse, which supposedly condemned all ‘black-skinned peoples’ to eternal inferiority. Sadly, some missionaries were quite efficient, and a few older Aboriginal people still believe they are condemned by God to be ‘less than whites’. In this vein, it is important to know that Aboriginals have never been given the critical tools to understand the Christian Bible fully. From the very first missions to later, more organise denominational initiatives, the Australian churches ‘read-out’ the meaning of the text of the Bible in a way that distorted more than just the words. The churches had the benefit of thousands of years of analytical study of the biblical text, and yet they consistently omitted from their interpretations the numerous instances of black people— and people of colour—in the scriptures. On the whole, Western Christian missions have left a legacy of a ‘missionised theology’ that continues, to this day, to have a negative impact on Aboriginal thinking. This way of doing theology remains self-righteous, judgmental, oppressive and full of institutionalised racism and sexism. There are various expressions of missionised theology being practised in Australia today. Nominal theology Over the years, many Aboriginal people have been forced into mission stations and reserves by ‘Christians of good will’. People in their thousands were ‘preached at’, ‘baptised’ and ‘converted’ to the Christian religion—often by force, sometimes by violence, and almost always under duress. Aboriginals were made to attend church services, sing hymns, go to Sunday school and so on. If they did not, their food rations would be cut, they would be isolated from other members of their family and community, or they would be ‘punished’ in some other way for their ‘heathenism’. Many Aboriginals became nominal Christians as they really had no other choice. In time, this forced contact led to theological osmosis. Aboriginals were survivors, and therefore they ‘absorbed’ white, European, conservative theology. This legacy continues today in Aboriginal fundamentalist, Pentecostal and evangelical expressions. Most—if not all—adherents of conservative theology reject their own Aboriginal identity, culture and languages. Most are concerned with personal sin and salvation, with individual conversion and piety, as opposed to institutionalised or corporate sins such as white racism and greed. They maintain a very narrow and apocalyptic worldview, believing that land rights and justice are all in heaven and that fighting for these here and now on earth is wrong, indeed sinful. Some acknowledge the existence of traditional spirituality, ceremonies and other cultural practices, but they generally discourage them. In one way or another, all of these conservative expressions deny various aspects of Aboriginal personhood, socio-cultural 11 identity and Indigenous religious being. They betray a direct, interventionist, white, European ‘missionised’ theology. Liberal theology There is a liberal tradition in Aboriginal theology. This is characterised by dependence—theological, ecclesiological, social, structural, economic— on Western church structures and entities. The representatives of this tradition are fiercely loyal to their denominational allegiances, but at times are open to working ecumenically. Motions and resolutions come easily, but direct action is not always forthcoming. • As far back as the 1930s, Tom Foster, an Aboriginal evangelist from La Perouse, raised important issues of justice and equality, and criticised white missionaries as constituting a destructive influence on Aboriginal people and culture. • In 1976 Pastor Douglas Nicholls (Churches of Christ) became Governor of South Australia, thus mixing a deep faith as a pastor with political commitment. • In the latter part of the 1970s, the Rev. Djiniyini Gondarra (Uniting Church) was part of the leadership of a major spiritual revival at Galiwin’ku, in north-east Arnhem Land. His writings have focused on this revival, and on ‘contextualising’ the Christian gospel for Aboriginal people. • In 1985 the Rev. Arthur Malcolm became the first Aboriginal Bishop in Australia, as Anglican Assistant Bishop of North Queensland. He is truly a gifted ‘pastor’, counselling and nurturing Aboriginal people in their pain, suffering, hope and visions. He is deeply committed to reconciliation. • Pastor Cecil Grant (Churches of Christ) is active in contextualising the gospel and is involved in lay theological education. • For many years, spanning this entire period, Pastor George Rosendale (Lutheran Church) has worked on a holistic approach to Aboriginal theology, encompassing traditional Dreaming stories as well as modern theological method. ACTIVITIES 1. Outline the position of the Aboriginal contributor to this section of this chapter in regard to the impact of religious traditions on Aboriginal people. 2. Explain the difference between ‘nominal theology’ and ‘liberal theology’. Story-telling theology Aboriginal story-telling theology embraces traditional and cultural teaching, and preserves a link between the Dreaming stories and the biblical scriptures. Many Aboriginal theologians use this form of teaching both to maintain the Aboriginal oral tradition and to bring Aboriginals a greater understanding of theology so that they can make it relevant to their daily lives. It is a non-Western, non-intellectualised method of teaching the highest truths about creation and life. By using the Dreaming stories, Aboriginal theologians are able to bring to life the teachings of the gospel, which may then be sung and danced to life through traditional Aboriginal ceremonies. One outstanding Aboriginal person who is very gifted in this tradition is Pastor George Rosendale, from the Hopevale community in far north Queensland. Through this practice he is able to make the gospel more meaningful and relevant to the Aboriginal way of life. Aboriginal theology Aboriginal theology is a radical movement in theology. It aims at creating an Indigenous theology, leaning heavily on the notion of biblical justice. It is autonomous (post-Western, postdenominational) and emphasises liberation, prophetic obedience, and action. It treasures traditional Aboriginal religion as the divine grounding for contemporary faith and identity. It keeps traditional practices such as ceremonies as potent reminders of important cosmic and temporal truth. And it holds the Dreaming as a timeless guide for active engagement. • In the 1960s the Rev. Don Brady worked with the Methodist Church in Brisbane. He was a gifted and passionate preacher, and a tireless campaigner for Aboriginal rights. He was always to be found leading Aboriginal land rights marches. His strong theological stance, combined with his persistent efforts at direct action for justice, eventually led the church to remove him from the ministry—a measure that broke him. • In the 1970s the Rev. Charles Harris followed Brady in the ministry in Brisbane. His work continued the prophetic stands for justice, eventually culminating in his vision of the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress in 1985. His subsequent writings reveal a true passion and thirst for justice. • In 1975 Patrick Dodson became the first ordained Aboriginal Roman Catholic priest. Like Brady and 12 Harris, his stands were far too threatening for the hierarchical, institutionalised church, and he left both the priesthood and the church. These great leaders have been followed by others with a strong theology and passion for justice. Fr Dave Passi, a Torres Strait Islander priest of the Malo cult, is also a fully qualified and ordained priest of the Anglican Church of Australia. He was one of the five original plaintiffs in the landmark native title (Mabo) land rights case, which shattered the legal fiction that the Australian continent was terra nullius. Passi was led by his strong theological commitment to justice. The Rev. Dhalanganda Garrawurra (Uniting Church) was assistant to the president at Nungalinya College in Darwin—this despite the fact that he was denied food rations by Christian missionaries when he did not go to church on the Aboriginal reserve as a youth. Though he probably did not consider himself to be an Aboriginal Christian theologian, Kevin Gilbert (1933–1993) nevertheless provided one of the most comprehensive critiques of Christian theology and Christianity itself. His works demonstrated vast knowledge of both the Bible and Christianity, though he stood at the fringe of Christian hermeneutics. His sharp insights offered a major contribution to Aboriginal theology. Aboriginal theology encompasses everything from the timeless oral tradition of Dreaming stories to the modern written tradition of biblical scholarship. It preserves the ancient wisdom of Aboriginal culture and tradition, and also reinterprets and reformulates more recent Western theological concepts. It is very diverse and has much to offer to those who are willing to learn. The Aboriginal and Islander Commission of the National Council of Churches in Australia Finally, as an organisation, the Aboriginal and Islander Commission of the National Council of Churches (NCCA) in Australia during its first decade took unprecedented and dramatic strides towards discerning and embodying an Aboriginal, autonomous theology. In 1991, under the leadership of Dr Anne Pattel- Gray, Aboriginal religion/spirituality took the World Council of Churches (WCC) by storm. Demonstrated throughout the WCC Seventh Assembly in Canberra, Aboriginal music, art, dance and spirituality took precedence on a world platform. This was the first time Aboriginal religion/spirituality had been showcased to the world. It was to have a lasting impact, challenging the world of religious leaders to open the door for future conversations with the Aboriginal world. ACTIVITIES 1. What is ‘Aboriginal theology’? 2. How does this theology treat the Dreaming? 3. Outline the work of the Rev. Don Brady and others in this movement. 4. Research the Aboriginal and Islander Commission of the National Council of Churches in Australia and the work it has done for reconciliation. 5. How have such organisations, including recently the World Council of Churches, helped the process of reconciliation? REVIEW AND ASSESS 1. To what extent is Aboriginal religion a way of life? 2. Prepare an oral report for the class on the importance of native title to the land rights movement in Australia. 3. Debate: The link between the Dreaming and the land rights movement was made for political reasons.’ 4. Prepare a visual and textual presentation on the importance of kinship to Aboriginal spirituality. 5. Research the Wik decision and form a hypothesis on the impact of the decision on the land rights movement. 6. Describe the connection between the Dreaming and the land and their interrelationship with Aboriginal spirituality. 7. Account for the religious landscape in Australia today in a visual display of the various religions and their history. 8. Discuss the diversity of religious traditions present in Australia today. 9. Evaluate the importance of interfaith dialogue to multi-faith Australia. 10. Describe the rise of New Age religions in Australia and discuss their impact on religious expression in Australia today. 13 11. Explain the impact that immigration has had on the religious landscape of Australia in the latter part of the 20th century. 12. Describe the role of the various religious traditions in the process of reconciliation. EXAM STYLE QUESTIONS MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS 13. Aboriginal people received recognition as Australian citizens in: a. 1901 b. 1938 c. 1967 d. 1972 14. Aboriginal liberal theology has developed from: a. the union of Presbyterian, Methodist and Congregational churches b. the forced acceptance of Christianity c. nominal theology d. Aboriginal Christians who operate from a Western-style church model 15. The 1986 Australian census figures show that: a. Anglicans outnumber Catholics b. Uniting Church members number more than Anglicans c. there are more members of other religions than the total number of Christians d. the number of people who stated ‘No religion’ was greater than the number of Christians. 16. The Church of England in Australia changed its name in 1982 to become known as: a. the Uniting Anglican Church b. the Anglican Church c. the Church of Anglicans in Australia d. the Anglican Church of Australia 17. The Uniting Church was made up of: a. Presbyterians, Methodists and Baptists b. Anglicans, Catholics and Methodists c. Presbyterians, Baptists and Anglicans d. Methodists, Presbyterians and Congregationalists 18. The fastest-growing Christian denomination is: a. Catholics b. Anglicans c. Pentecostals d. Orthodox 19 Denominational switching is common within: a. Christianity b. Hinduism c. Buddhism d. Islam 20. Which of the following factors did not contribute to the stolen generations? a. missionisation b. reserves c. the arrival of Europeans d. totems 21. When people use the term ‘self-determination’, they mean that: a. people are able to determine and control their own business b. the authorities determine the affairs of others c. Indigenous people have assigned responsibility to white authority figures to determine their future d. none of the above 22 ‘Native title’ is another name for: a. Wik b. Mabo c. Yolngu d. Koori 14 SHORT RESPONSE (5 MARKS) 23. ‘The churches should act together in all matters except those in which deep differences of conviction compel them to act separately.’ Conference on Faith and Order, 1952 Using the above statement and your own knowledge, describe the impact of Christian ecumenical movements in Australia. (Studies of Religion II HSC Examination Paper © Board of Studies NSW for and on behalf of the Crown in right of the State of New South Wales, 2007) 24. Discuss the contribution of Christianity to social welfare since 1945. 25. Explain the impact of the Wik decision on the land rights movement. 26. Describe the role of one religious tradition in rural and outback Australia. 27. ‘For Aboriginals, the correlation between their created world, their social world and their spiritual world means that their religion is holistic and living, that it touches everything.’ Discuss. 28. Explain the importance of kinship to Aboriginal people. 29. What is the importance of the ‘sacred’ to Aboriginal people? 15