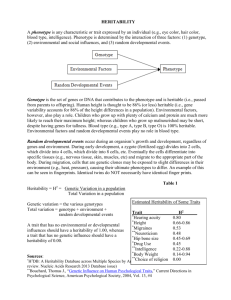

HERITABILITY

advertisement

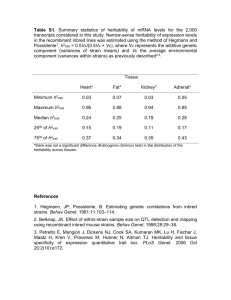

HERITABILITY The total variability observed in a randomly breeding population existing in an unrestricted environment is a function of the variation due to genetic diversity, environmental diversity, and their interaction, as shown in equation [1]: [1] Vt = Vg + Ve + Vi, where Vt = variability observed in the population Vg = variability attributable to genetic variation Ve = variability attributable to environmental variation Vi = variability attributable to gene x environment interactions Vi is assumed to be negligible, reducing the formula to: [2] Vt = Vg + Ve. If either Vg and Ve are known, the other can be obtained by subtraction: [3] Vg = Vt - Ve and [4] Ve = Vt - Vg. Ve is difficult to directly estimate or eliminate whereas Vg is easy to eliminate by using inbred strains or identical twins (Vg = 0). For genetically homogeneous populations, [5] Ve = Vt. This value of Ve is then plugged back into the equation for the randomly-bred population to calculate Vg: [6] Vg = Vt - Ve Heritability refers to the amount of variability attributable to genetic variation, divided by the total observed variability: [7] H2 = Vg/Vt So, a heritability quotient of .8 means that 80% of the observed population variability is due to genetic variability. There are many problems with analyses of this sort, the most fundamental being the assumption that the effects of genes and environment are additive, when an interactive (multiplicative) model is almost certainly more correct; i.e., the interaction term is seldom insignificant. Thus, the estimate of Vg in equation [6] is inflated because it is really an estimate of Vg + Vi. That is, variability due to gene x environment interactions is attributed solely to genes. Another major problem with twin studies is that twins share the same intrauterine environment. Thus, hormones, nutrition, drugs, etc. that can have profound impact on subsequent maturation of the brain and behavior are shared by the twin fetuses. Because there is a gene x environment interaction term in the case of fraternal twins but not in the case of identical twins, one will mistakenly attribute to genes any prenatal effects of gene x environment interactions on subsequent behavior. Finally, even if one accepts the assumptions of additivity and a negligible interaction between genes and environment, heritability only measures the relative variability of genetic and environmental contributions, not the degree to which a trait is inherited, as some people mistakenly believe. To illustrate: If the environment is held constant in an experiment in order to assess the contribution of genetic factors, then Ve = 0, Vg = Vt, and heritability = 1. Conversely, if one examines that same trait using an inbred strain that is homozygous, then Vg = 0 and heritability = 0. Obviously, the degree to which the trait is genetically encoded or inherited is not different in the two experiments. Thus, heritability is not an estimate of the degree to which a trait is genetically transmitted. Nonetheless, many people use heritability estimates to show that a trait is "innate." For example, Arthur Jensen and William Shockley pointed to heritability estimates ranging between .6 and .8 to support their arguments that the difference in the performance of blacks and whites on I.Q. tests is genetically based. Not only are those estimates fiction because the gene x environment interaction is ignored as described above, but Jensen has argued that environmental manipulations such as Project Head Start are a waste of time, money and effort because I.Q. is an inherited trait.